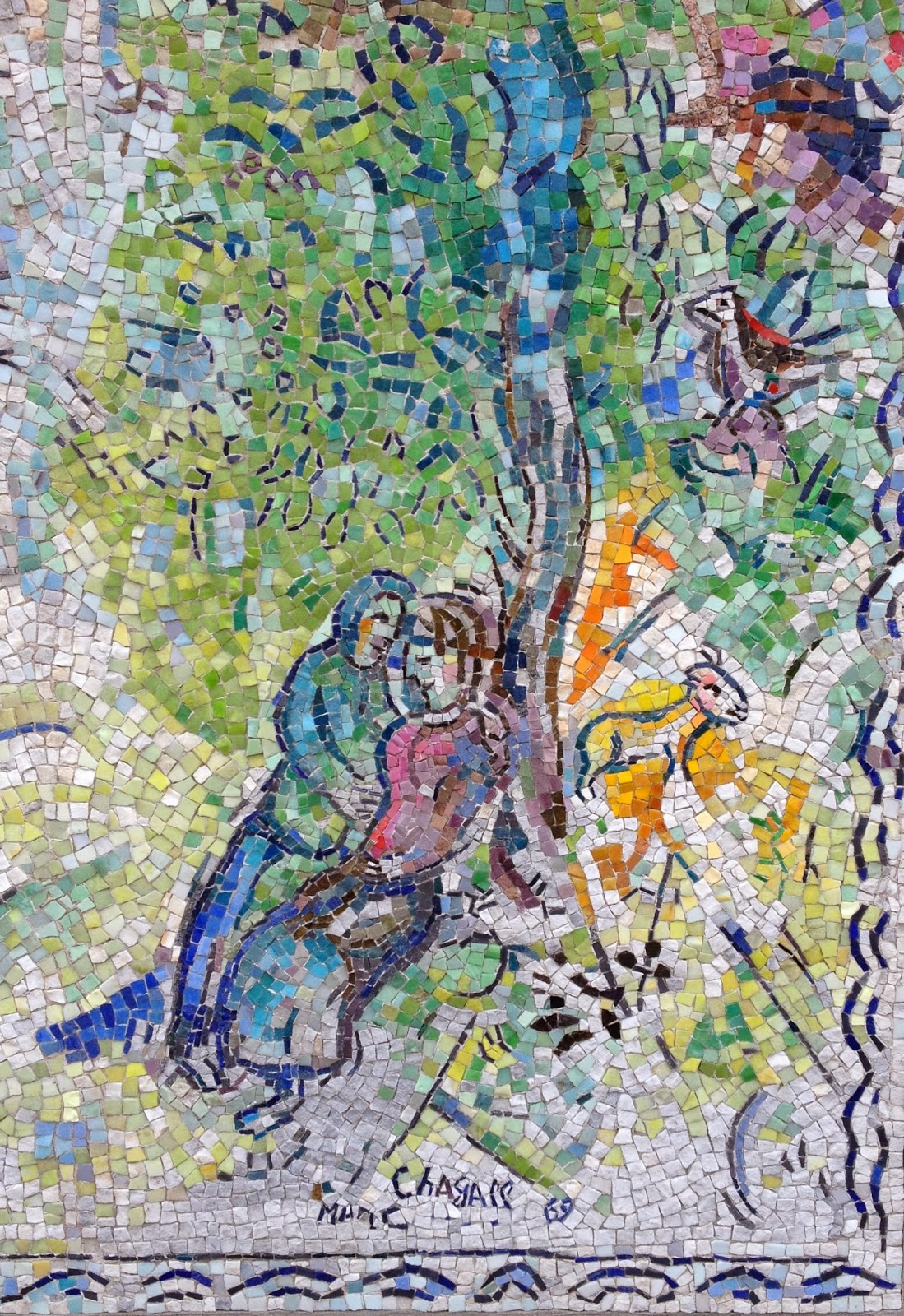

| Detail – Marc Chagall, with Lino Melano, Orpheus, 1971, from the upper right side–Pegasus, Three Graces, Orpheus |

The nation’s capital city added a sudden burst of color this season in the form of Marc Chagall’s Orpheus, a glass and stone mosaic. It’s a 17′ by 10′ wall standing in the National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden, between 7th and 9th Streets, NW, Constitution Avenue and Madison Avenue. Evelyn Stephansson Nef, who died in 2009, donated it to the museum. (The composition is one of three new acquisitions in the National Gallery, a must-see along with a Van Gogh, a Gerrit von Honthorst and a loan of the Dying Gaul from the Capitoline Museum in Rome.)

The mosaic stands in the garden behind the restaurant, but in front of the heavily traveled Route 1. Fortunately, a lot trees shield it from view of the traffic, providing a reflective space for viewers. The sculpture garden is on the National Mall, but open only from 10-5 daily and 11-6 Sundays, except for an ice rink in winter which has longer hours.

Evelyn Nef and her husband, John Nef, were friends of the artist who was inspired after visiting them in 1968. The artist gave the mosaic to the couple back in 1971. For years, it was in the garden of their Georgetown residence, vaguely visible from the street. The National Gallery spent years preparing, repairing, moving and re-installing its 10 separate concrete panels, a process described in the Washington Post. The seams aren’t visible.

|

| Detail, Marc Chagall, Orpheus, 1971. Here Orpheus is crowned and holds his lyre. |

Chagall did the drawings for the composition in his studio back in France, and then hired mosaicist Lino Melano to complete it. Melano supervised installation which was finished in November, 1971. The artist returned at the time to see it. It was his first mosaic installed in the US. Afterwards, Chagall did the renowned Four Seasons mosaics for the First National Plaza in Chicago.

The composition has the spontaneity, verve and joy we can expect from Chagall. The execution, however, took a highly skilled Italian mosaicist who was steeped in the tradition. Melano used Murano glass, natural-colored stones and stones cut from Carrara marble. On close inspection, viewers can discern where there is glass: in the most brightly-colored passages, the shining blues, reds and radiant yellows. There is a touch gold leaf behind some of the glass, a technique inherited from the Byzantine mosaicists.

(For a good comparison, Byzantine mosaics are currently on view in the marvelous National Gallery Exhibition, Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Art from Greek Collections, until March 2, 2014.) Byzantine mosaics also combine stone cubes and glass cubes, called tesserae, but the tesserae are much, much smaller in Byzantine mosaics.

Melano wisely reserved the gold leaf for a few choice places, but only on Orpheus, his crown and his knee.

|

| Detail, Marc Chagall, Orpheus, mosaic, 1971. Figures cross the ocean, with an angel guide, the sun and mythological horse, Pegasus |

The god Orpheus is shown without his ill-fated mortal lover, Eurydice. Eurydice lost him because she disobeyed fate and dared to turn back and look at him while in the underworld. Chagall ignores the pessimistic part of the story. How then do we interpret what Chagall was trying to convey?

The other mythological figures are the flying horse Pegasus and the Three Graces. The winged-horse does not have feet, reminding me of the incomplete depictions of animals painted in the caves of southern France, near Chagall’s studio. Orpheus holds his lyre in a prominent position. Pegasus flies and Orpheus makes music while a little birdie flies. The Graces are not dancing here, but they remind us of our gifts and that grace is indeed possible. Chagall, who escaped Europe in the Holocaust, had a knack for putting a positive spin on events. He obviously chooses the highest potentials of human nature, while not exactly ignoring the negative.

|

| Detail, lower left corner with Chagall’s signature |

Of course the myth of Orpheus also conjures up images of the underworld. On the left, there is water where people are entering in groups and fishes are swimming. Could this be the River Styx of Greek mythology? Chagall said it referred to the groups of immigrants who crossed the ocean to get a better life. Above the river is a huge burst of sun. An angel flies triumphantly overhead, with open arms. The artist ignored the rules of perspective and foreshortening on this figure, reminding us that flight, or overcoming limitation, is indeed possible. He suggests that dreams can come true.

A dreaming couple on the bottom right hand side are happily in a paradise, under a tree. The artist’s signature is underneath. Chagall may have thought of himself with his wife, Bella. According to the National Gallery’s website, Evelyn Nef asked Chagall if this was her and her husband, John. He replied, “If you like.” There’s a border to the composition. Everywhere lines are curved, making this composition the image of life as a joyful journey, a graceful dance with much optimism.

Recent Comments