by Julie Schauer | May 23, 2017 | 19th Century Art, Cezanne, Emile Zola, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

|

| “Cézanne et Moi.” L- Guillaume Canet as Emile Zola, R-Guillaume Gallienne as Cézanne |

The French film, “Cézanne and I” or “Cézanne et Moi,” will be of most interest to those who know the story of Cézanne’s lifelong friendship with Émile Zola. Guillaume Gallienne, an actor with the Comédie Francaise gives an outstanding performance as Cezanne, zeroing in on his character. The actor who plays Émile Zola, Guillaume Canet, is also quite believable. The film direction tells the story extremely well. In addition, the production team captures the colors and aesthetics well enough to make the viewer feel he or she is there.

|

A studio that Cezanne kept within the

Bibemus Quarry |

The film, “Cézanne and I” explores Cézanne’s character through the friendship with Zola and his relationship with others–wife, mother, father, and how it relates it to his art. Director Daniele Thompson picks up on the many mysteries of these relationships, the personality of the man, and his inner character. Most of the film portrays Zola as a less complicated character than Cezanne, easier to understand as a person. Many people will want to see it to experience the landscape of Aix, which is beautiful. Criticism of the film comes from those who don’t understand the dialogue, but again it helps to have some knowledge of the history of the friendship.

The most influential 20th-century artist, Picasso, said he owed everything to Cézanne. Matisse claimed “he’s kind of a god of painting.” Recognition and acceptance were elusive for Cezanne during most of his career. As for Émile Zola, many French of today still claim him as their favorite novelist. So to think that these two giants of late 19th-century French culture were classmates and best of friends growing up is amazing. It’s also a tribute to the school in Aix-en-Provence which nurtured two extraordinary geniuses.

Fortunately, the movie takes you through some of the beautiful scenery they roamed through in childhood, such as the trails around the Bibémus Quarry and Mont Saint-Victoire. There’s a glimpse at the richness of color which he portrayed so well in his paintings, with that perfect balance of warm and cool colors. The movie didn’t show the beautiful house he eventually inherited from his parents.

|

| Mont Saint-Victoire from Bibémus Quarry at the Baltimore Museum of Art |

Cézanne was the very first artist who really interested me–probably because of his colors. In high school, I was given the assignment to choose an artist to study and try to paint in his style. I chose Cézanne and it was difficult. In grad school, I was required to read Émile Zola’s novels, Nana and The Masterpiece. The Masterpiece is about an obsessive and determined artist who ended up being a complete loser. When it was published in 1886, Cézanne interpreted it to be entirely about himself. The descriptions of their childhood wanderings together were true to life. I don’t remember the book so well, but I thought more Degas than Cezanne while reading it. Zola was already a rip-roaring success as a novelist by the time he wrote it, and very prolific. The Masterpiece must have seemed like a slap in the face to Cezanne who was just as talented and worked as hard. Cézanne was 47 years old, but, as an artist, he only knew rejection at that time. His recognition did not come until 10 years later — when in his late 50s.

My understanding was that Cézanne was so offended by the portrayal (parts of it are read in the film) that he would never speak to Zola again. In the movie, they are in contact again. From the film, I actually sympathize a great deal with both Cézanne and Zola. Zola claimed that Lantier, the artist in the novel, was a composite of artists he had known. It doesn’t help that he describes their childhood friendship pretty much as it was. In Zola’s novel, Lantier ends up killing himself, which certainly must have suggested to Cezanne the worthlessness of his artistic endeavors. However, the ending is consistent with Zola’s style of naturalism which exposes the brutalities of life. As far as I know, none of the painters Zola knew actually took their own lives. In reality, Cezanne was rarely satisfied with his own painting, even after he received some recognition.

|

| Bibémus Quarry, near Aix-en-Provence, one of the many landmarks the artist painted |

The time period was great for artists and writers mutually supporting each other, hanging out the cafes together, a tradition that continued through the 1920s. Both Zola and Cézanne went to cafes and on social excursions with Manet and the Impressionists. However, Cézanne was frequently opinionated and offensive and, at the same time, more withdrawn than the others. After a few years, Cézanne retreated back to his native Provence while Zola stayed in Paris.

|

| The trails near Bibemus Quarry |

The move flashes between childhood, early adulthood and various events in their lives. There is a third friend named Baptistin who became an engineer, but also was a part of their threesome. Zola’s father died when he was young and his mother struggled to support him. Cézanne was rich; his banker father wasn’t initially supportive of his chosen profession. As an adult, he was consciously rebelling against his father whom he considered a social climber. As might be expected, Zola became bourgeois and played the part of worldly success quite well. Cézanne rejected many of the social graces, and was considered uncouth and boorish by some. Certainly, many great artists also fit the stereotype of being complete slobs, such as “big, grubby Tom” Masaccio and the great Michelangelo.

Cézanne was temperamental, as artists often are. It comes with the territory of obsessiveness. He frequently tore up his paintings. It’s the frustration that is expressed by Lantier, the artist in Zola’s novel. He stuck to his goals until the very end, but was never satisfied with his painting. He died at age 67.

Cézanne got along well with Camille Pissarro, the oldest of the Impressionists and somewhat of a mentor for all artists in the group. They had a strong rapport and mutual respect. Cézanne and Édouard Manet (my other favorite artist from the period) did not like each other. This lack of compatibility is curious to me because some of their artistic goals (the way they see form and structure) appear somewhat similar. Each is important for redefining the structure of painting through innovative means of composition that rejected traditional foreground, middleground and background. Both artists were from well-to-do backgrounds, but the elegant Manet, is known to have thought of Cézanne as ill-mannered and coarse. Both artists received much public derision and criticism, but the younger artists of the avant-garde loved Manet.

|

| A scene near Aix-en-Provence |

The movie even puts Cézanne next to the gorgeous Berthe Morisot, known for her refinement and close relationship to Manet. My personal impression is that Cézanne suffered from jealousy of Manet on many levels, especially since Manet was so admired by his fellow artists. His good friend Zola had written a well-known and important article in defense of Manet. Zola also defended Cézanne and the other artists who were Impressionists through his essays. However, Zola’s novel, The Masterpiece expressed less respect for their style than one might expect.

|

Cézanne, Mme Cézanne in Yellow Armchair

Art Institute of Chicago |

Cézanne’s portraits of his wife have always amazed me for their detachment and lack of feeling. Was he at all in love with her? According to the movie, he loved her because she could sit hours without moving. None of his portraits of her show love or any feeling at all, and Thompson explores why. The filmmaker also suggests that Cezanne and Zola’s wife had at one time been involved — before she married his friend. I’m not sure if that’s the truth or just the filmmaker’s conjecture.

Most of Cezanne’s portraits are all about the structure and composition of the painting. The love in Cézanne is found mostly in his portrayal of nature particularly in portraits of the mountain he idolized, Mont Saint-Victoire.

There is feeling in the self-portraits — the feeling of intensity and determination in his eyes. I think his self-portraits are excellent because they capture the strong shapes with contrasts of color. From these we can trace the formal properties that lead to the Cubist style of Picasso and Braque.

Quality films about artists help us to understand how an artist’s mind works. This film helps us understand the artist more through his relationships rather than through the art itself. (I personally have a hard time teaching Cézanne.) The theme of denying his feelings and not showing that he cared for others comes up again and again. It’s a selfishness that is in pursuit of art, and/or, ego. Yet, if had been only about ego, Cézanne would have given up years earlier. He is an artist who died painting.

|

| Self-portrait, Winterthur Collection, Switzerland |

In 2011, I went to his home in Aix-en-Provence, his studio and Bibemus Quarry where he did so many paintings. I will never forget the excellent tour guide at Bibemus Quarry, a landmark that inspired Cézanne so much. The colors of those rocks really are the rich yellow ochres and reds that we see in Cézanne’s paintings. The quarry had been used for buildings since Roman times, but the rocks had become too salty and sandy and it was abandoned in the 1800s. You can really understand how the quarry’s strong, virile presence inspired Cezanne. I realized that Mont Saint-Victoire and Bibémus Quarry are much further away from each other than in the impression from Cézanne’s painting in Baltimore, shown above.

Photographer Phil Haber’s blog of Cezanne really captures the beauty of his scenery today. However, Phil had to put together a composite of two photos to get the view seen in the Baltimore painting. Cézanne’s compositions are reality, but reality from a rearranged view.

How does this fit into the history of art and literature? Zola’s writing is naturalism and he is important for describing things and the social classes with a gritty truth of lower-class life. Impressionists were more inclined to overlook the brutal side of life. Renoir painted the working class of Montmartre, but he idealized them–turning them into angelic figures. Degas painted ballet dancers and laundresses, stressing the vigor of their work. Zola has more in common with Courbet, Degas and early Manet.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2022

by Julie Schauer | May 14, 2017 | An Object of Beauty, DeKooning, Sotheby's, Steve Martin, Warhol

|

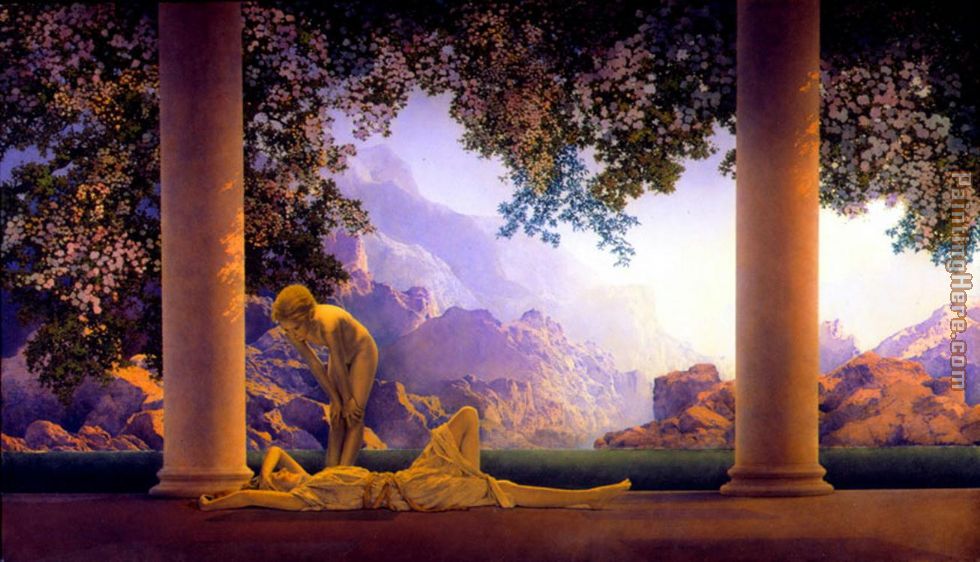

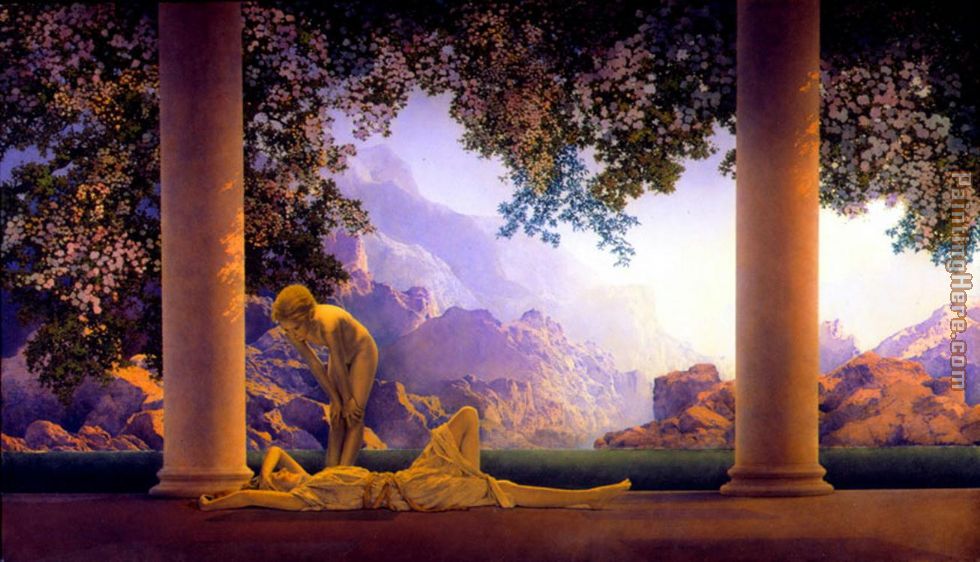

| Maxfield Parrish, Daybreak, 1922 |

An Object of Beauty, is a surprising novel by a man of many talents, Steve Martin. Last year, in the Spring, I had seen a musical by him in New York and was then surprised to get this book as a Mother’s Day present. Not only is it an original novel, but it shows that Steve Martin is a gifted interpreter of both art and the art world. The novel exposes the mystique and glamor of the art world, together with its sleaze.

To be honest, valuing art primarily for its monetary or investment value really offends me. I briefly worked in the 80s at the art gallery considered one of Chicago’s leading contemporary galleries at the time. It was surprising to go from a show of DeKooning’s latest works (painted with mayonnaise) to one of photographs of Racquel Welch (by an important photographer). Although these exhibitions generated a ton of publicity, they actually sold very little — just one DeKooning and none of the Racquel Welch photographs. (sh….that was an art world secret.)

To be honest, valuing art primarily for its monetary or investment value really offends me. I briefly worked in the 80s at the art gallery considered one of Chicago’s leading contemporary galleries at the time. It was surprising to go from a show of DeKooning’s latest works (painted with mayonnaise) to one of photographs of Racquel Welch (by an important photographer). Although these exhibitions generated a ton of publicity, they actually sold very little — just one DeKooning and none of the Racquel Welch photographs. (sh….that was an art world secret.)

Martin understands that the glitter of the art world which is hiding beyond a multitude of facades. The narrator is an art critic with a curiosity about, or a crush, on a fellow art history major he knew from college. Her name is Lacey. The story winds through the years, beginning with the author’s idealization of Lacey through various stages of recognizing and figuring out what makes her tick. Lacey lands a minor, low-paying working for Sotheby’s in New York and ends up owning a gallery in edgy Chelsea. Most of the men (and women for that matter) in her life are expendable and she plays them well. Others are into the game, but don’t play it as well as she does. Through clever gamesmanship and some fraudulent moves, she makes financial gains. At one time she was fired from Sotheby’s, but it was just an easy road to the next, better-paying job.

Lacey’s character and the situations she is in revealed to me, once again, why I’m glad to have not gone down that career path. Sometimes the situations are humorous, even the names of an artist, such as Pilot Mouse (a pseudonym) or the collectors. But, as Steve Martin explains, “The theory of relativity applies to art: just as gravity distorts space, an important collector distorts aesthetics. The difference is that gravity distorts space eternally, and a collector distorts aesthetics only a few years.”

Martin also describes the galleries of Chelsea which distinguished themselves with art that was “difficult” — “art that made you feel they possessed the cabalistic code that unlocked the inner secrets of art.”

Martin humorously nails the art critics: “‘In dialogue’ was a new phrase that art writers could no longer live without. It meant that hanging two works next to or opposite each other produced a third thing, a dialogue….It also hilariously implied that wen the room was empty of viewers, the two works were still chatting. I was tolerant when he said ‘in dialogue’ because I can get it, but when he said ‘line-space matrix,’ I wanted to puke.” He was describing Art Basel in Miami.

The economy has boomed a lot since I worked at a gallery and the ups and downs of the market have been much more dramatic. Some paintings, the objects of beauty, go from being greatly undervalued to overvalued. To the same is true of Lacey, whom the author seems to regard as the ultimate “object of beauty.” The centerpiece painting of the novel is by Maxfield Parrish, well-known in the 1920s but not appreciated as much today. Much suspense goes on in the novel and at one point I thought the dealer she worked for had been involved with the famous art heist of 1990. The twists and turns of the novel are crafted well. At the conclusion, the economy crashes as it did at the end of the 2000s. Lacey was brought back down to earth, but so was the author.

Finally, I appreciate his descriptions of Pop Art ……….and Andy Warhol. “It was easy to give Pop critical status–there were lots of sophisticated things to say about it–but it was tougher to justify the idea that repetitive silk screens were rivals of great masters.”

In the course of the novel, Lacey buys a Warhol print in the early 90s and then sells it when she’s starting the art gallery, after it had really gone up in value. “If Cubism was speaking from the psyche, then Pop was speaking from the unbrain, and just to drive home the point, its leader Warhol closely resembled a zombie.”

Steve Martin is witty and wise. Other artists he describes include Milton Avery (gifted 20th century American), Rockwell Kent, trompe l’oiel artists Peto and Hartnett, and DeKooning. He’s really a Renaissance Man.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

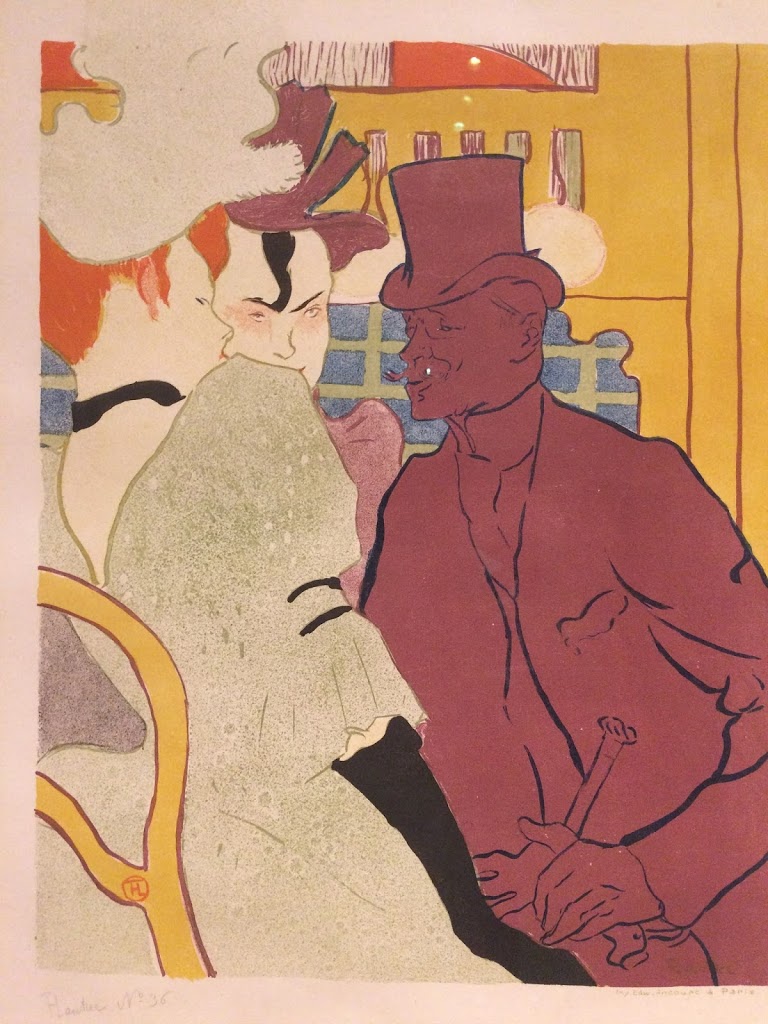

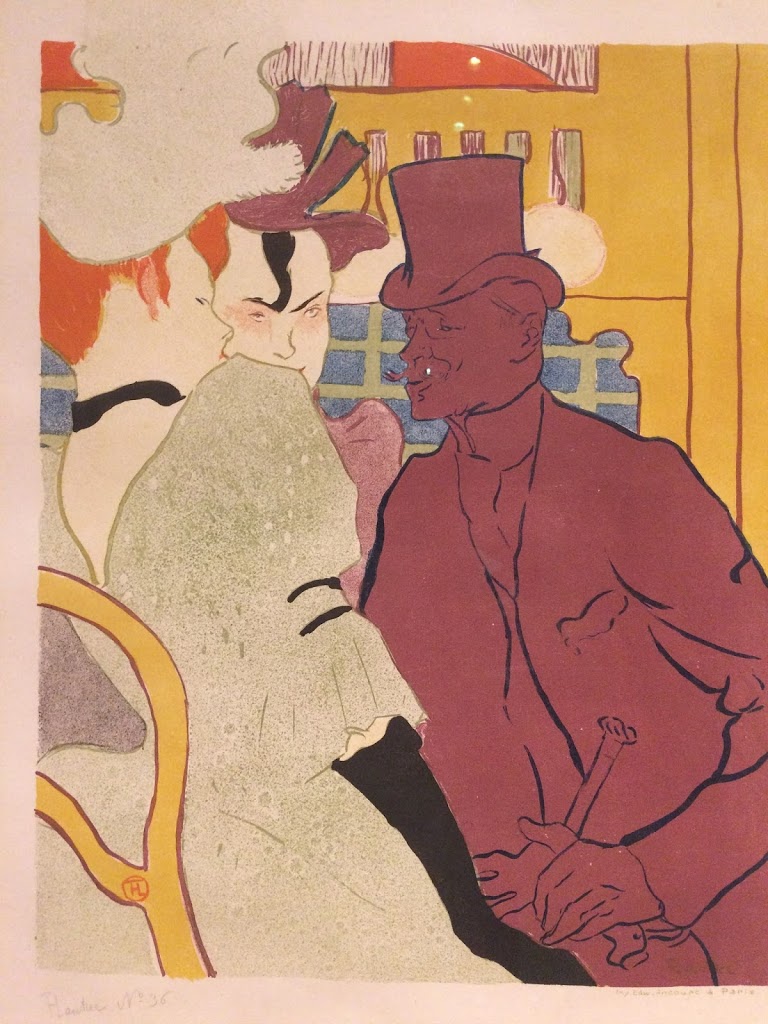

by Julie Schauer | Apr 29, 2017 | 19th Century Art, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Printmaking, Toulouse-Lautrec

|

The Artisan Moderne. 1896, Lautrec was asked to advertise a jeweler/home goods designer

He manages to add some of his own thoughts and observations about human nature. |

This is the last weekend of Phillips Collection’s exhibition,Toulouse-Lautrec Illustrates the ‘Belle Epoque.’ The Phillips organized the show with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, its only other venue North America. This exhibition is different and distinguished from other exhibitions of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (and I’ve seen a few of them), because it’s primarily graphic art and contains some works that we don’t normally see. There are trial proofs alongside the finished prints, and a few very rare prints. The entire show comes from one private collector in France and we’re very lucky to have it for a short time in Washington.

|

Mademoiselle Eglantine’s Troupe, 1895- 1896 Brush, spatter and crayon

lithograph in three colors. The dance troup included Jane Avril, seen below |

Toulouse-Lautrec’s color is magical but it’s really his sensational line that was his greatest gift. He follows a string of other great 19th century line artists: Ingres, Daumier, Degas and Hokusai, but he broke entirely new ground in the world of graphic art. In this exhibition, some of the familiar posters are shown in different stages, and it’s a great starting point to understand something of the lithographic process. Lautrec mastered the medium of color lithography, using multiple stones for the different colors of ink.

He’s best known for creating poster advertisement for entertainers and other highlights of Paris night life. Certainly he did a lot to bolster the careers of certain singers and performers such “La Goulue,” Jane Avril and Aristide Bruant. His posters were all over the kiosks of Paris and his work began a new trend. Although Lautrec was from an aristocratic background, he reveled in the demimonde and the bohemian lifestyle. He captured the people, places and events with so much vitality that the viewer almost wishes he or she could be there. The “Belle Epoque” is the beautiful era and in the USA it reflects the time of “The Gilded Age or “The Gay Nineties.”

|

| Jane Avril, 1899 |

Depicting the subjects with wit and whimsy, and it’s clear that Lautrec’s art always captured much more than a photograph could. Sometimes his faces seem to be sneering at us. His expressive, calligraphic line is pure magic in how it captures a quick impression. He also masters the integration of letters into design, an essential for good graphic art. He portrayed Jane Avril several different times — in 1893, in t

he Divan Japonais, with

Mademoiselle Eglantine’s Troupe and again in 1899. The poster of Jane Avril from 1899 is particularly effective in design. Her undulating lines take up the entire picture from top to bottom, twisting to the right and then off the page on the left. It’s utterly simple, but effective design

Furthermore, it’s not only performers and night clubs that he enjoys. One of his friends, Sescau asked him to advertise his photography studio. He sets the fashionable lady in the foreground, running away from the photographer. With his sly humor, he makes suggests that photographer friend is looking at her in other ways, too. In a brilliant display of his design talent, the frills of this woman’s flowing cape match the rhythms of design in her fan, flowing in the opposite direction off the edge of the page.

|

Photographer Sescau, 189 Brush, crayon and spatter lithograph, printed in five

colors. Key stone printed in blue; color stones in red, yellow and green |

Like other artists of his time — Van Gogh and Munch — he used jumps in space to heighten the meaning. It works well with the poster; the graphic artist’s challenge is to say a great deal with a minimal amount of detail and definition. In one of his most famous works, La Goulue at the Moulin Rouge, the master of ceremonies is at the picture plane. He’s merely a silhouette with pointed fingers, pointing to the artist’s signature put also to the celebrity whose dancing a can-can. Le Moulin Rouge was a 1890s version of “Dancing with the Stars.” Guests were able to mix and mingle with their favorite celebrities, and to dance alongside them.

|

| La Goulue (Louise Weber) |

Of course the Moulin Rouge was also memorialized with a fictional character played by Nicole Kidman in Baz Luhrmann’s 2001 movie, Moulin Rouge. The story, but not the aesthetics in the move, fit with the time and place. John Leguizamo played Toulouse-Lautrec as an affable, good-natured character. Since childhood accidents and perhaps a genetic disease kept him from growing to normal adult height, he felt comfortable with other outsiders.

In actuality, La Goulue was Louise Weber, who had moved from the country (Alsace) into the city as a teen. She was approximately 24 at the time of her stardom as one of the most popular dancers in Paris. Her nickname, “the glutton” probably refers to how she took from others — food and drink.By the time she was 30, she was tired, wasted, impoverished and alcoholic. (In his prints, and paintings, she’s always recognized by her topknot. ) Unfortunately, there’s similar sad tales played out by some young stars today.

|

La Goulue at the Moulin Rouge, Brush and Spatter lithograph, printed

on two sheets of wove paper. Final print

|

Many other famous posters are on view in full splendor, including images of Aristide Bruant and Marcelle Lender. This must-see exhibition is pure visual delight. It also offers a great deal of technical information about Lautrec’s astounding graphic techniques. This is just a small sampling of the many fantastic posters, paintings and graphics that are part of the exhibition.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments