by Julie Schauer | Feb 25, 2014 | Byzantine Art, Cathedral of Hildesheim, Christianity and the Church, Exhibition Reviews, Metalwork, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mosaics, National Gallery of Art Washington, The Middle Ages

Archangel Michael, First half 14th century tempera on wood, gold leaf

overall: 110 x 80 cm (43 5/16 x 31 1/2 in.) Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens

Gold radiates throughout dimly-lit rooms of the National Gallery of Art’s exhibition, Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Art from Greek Collections. Some 170 important works on loan from museums in Greece trace the development of Byzantine visual culture from the fourth to the 15th century. Organized by the Benaki Museum in Athens, it will be on view until March 2 and then at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles beginning April 19. The National Gallery has a done a great job organizing the show, getting across themes of both spiritual and secular life spanning more than 1000 years. The exhibition design is masterful and includes a film about four key Greek churches. The photography is exquisite and provides the full context for the Byzantine church art.

There are dining tables, coins, ivories, jewelry and other objects, but it’s the mosaics which I find most captivating, and this exhibition allows a close-up view. Their nuances of size and shape can be closely observed here, but not in slides or in the distance. Byzantine artists gradually replaced stone mosaics with glass tesserae, painting gold leaf behind the glass to portray backgrounds for the figures. It was the Byzantines created these wondrous images by transforming the Greco-Roman tradition of floor mosaics to that of wall mosaics.

|

| Van Eyck, St John the Baptist, det-Ghent Altarpiece |

|

|

New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art recently hosted another exhibition of the Middle Ages, “Treasures from Hildesheim,” works from the 10th through 13th centuries from Hildesheim Cathedral in Germany. Even though Greek Christians of Byzantine world officially split from Rome in the 11th century, the two exhibitions show that the art of east and west continued to share much in terms of iconography and style. Jan Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, from the 15th century, contains a Deesis composed of Mary, Jesus and John the Baptist, in its center, proving how persistent Byzantine iconography was in the West. That altarpiece shows the early Renaissance continuation of imagining heaven as glistening gold and jewels.

Church architecture evolved very differently however, with the Latin church preferring elongated churches with the floor plan of Roman basilicas. The ritual requirements of the Orthodox Church resulted in a more compact form using domes, squinches and half-domes. Fortunately, the National Gallery’s exhibition has a lot of information about Orthodox churches, their layout and how the Iconostasis (a screen for icons) divided the priests from the congregation.

|

| Reliquary of St. Oswald, c. 1100, is silver gilt |

Both cultures re-used works from antiquity. In the East, the statue heads of pagan goddesses could become Christian saints with a addition of a cross on their foreheads. In the west, ancient portrait busts inspired gorgeous metalwork used for the relics of saints, such as the reliquary of St. Oswald, which actually contained a portion of this 7th century English saint’s skull. Mastering anatomy, perspective and foreshortening was not as important an aim as it was to evoke the glory and golden beauty of heaven as it was imagined to be. The goldsmiths and metalsmiths were considered the best artists of all during this period in the west.

|

Mosaic with a font, mid-5th century Museum of

Byzantine culture, Thessaloniki

Photo source: NGA website |

|

|

|

Perhaps the parallels exist because many artists from the Greek world went to the west during the Iconoclast controversy, spanning most years from 726 to 843. Mosaic artists from the Byzantine Empire peddled their talents in the west, particularly in Carolingian courts of Charlemagne and his sons. From that time forward certain standards of Byzantine representation, such as the long, dark, bearded Jesus on the cross. While we seem to see these images as either icons or mosaics in Greek art, they become symbols in the west, often translated into sculptures of wood, stone or even stained glass.

An interesting parallel of the two exhibitions is the early Byzantine fountain, a wall mosaic of gold, glass and stone in the NGA’s exhibition, which compares well to the 13th century Baptismal font from Hildesheim, showing the Baptism of Christ. The font mosaic is from the Church of the Acheiropoietos in Thessaloniki. It is thought to emulate the fountains and gardens of Paradise. One can visualize of the context in which the fragmentary mosaic was made by watching the film in the exhibition, which shows another wondrous 5th century church in Thessaloniki, the Rotonda Church.

|

A Baptismal Font, 1226, is superb example of Medieval

metalwork from Hildesheim Cathedral. |

The exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum had a life-size

wooden statue of the dead Jesus, dated to the 11th century, originally on a wood cross, now gone. Wood carvers out of Germany were masters of emotional expression. In the iconic

Crucifixion image in the Greek exhibition, a very sad Mary and Apostle John are grieving at the side of Jesus. It’s poignant and emotional, with knit eyebrows, tilted heads and a profoundly felt grief.

|

| Golden Madonna is wood covered in gold, made for St. Michael’s Cathedral before 1002 |

|

The iconographic image of the Theotokos, a Greek type is normally a rigid, enthroned Mary who solidly holds her son, a little emperor. The format expresses that she is the throne, a seat for God in the form of Baby Jesus. From Hildesheim, there is a carved statue which dates to c. 970, carved of wood and covered with a sheet of real good. Both heads are now missing. At one time the statue was covered with jewels, offerings people had given to the statue. In the west, this type became common, called the sedes sapientaie, but the origin is probably Byzantium.

Although heaven is more important than earth, and God and saints in heaven are more powerful than humans, sometimes medieval artists have been capable of revealing the greatest truths about what it’s like to be a human being. In the icons, there is great poignancy and beauty in the eyes. At times the portrayal of grief is overwhelming, as we see on an icon of the Hodegetria image where Mary points the way, the baby Jesus but knows He will die. On the reverse is an excruciatingly painful Man of Sorrows.

|

| Icon of the Virgin Hodegetria, last quarter 12th century, tempera and silver on wood, Kastoria, Byzantine Museum. On the Reverse is a Man of Sorrows |

The Metropolitan exhibition of course could not bring the two most important works from Hildesheim, the bronze relief sculptures: a triumphal column with the Passion of Christ and a set of bronze doors for the Cathedral. Completed before 1016, I often think of the figures on the relief panels on those doors as one of the most honest works of art ever created. As God convicts Adam of eating the forbidden fruit, Adam crosses his arm to point to Eve who twists her arms pointing downward to a snake on the ground. We may laugh because God’s arm seems to be caught in his sleeve as he points to Adam. Though this medieval artist/metalsmith (Bishop Bernward?) may not have understood anatomy and perspective, he understood how easy it is for humans to pass the blame and not take responsibility for their actions.

|

| The Expulsion, before 1016, detail of bronze door, St. Michael’s, Hildesheim |

Medieval artists in both the Greek and Latin churches are normally not known by name. After all, their work was for God, not for themselves, for money or for fame.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 1, 2014 | Exhibition Reviews, Fiber Arts, Folk Art Traditions, Greater Reston Arts Center, Local Artists and Community Shows, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Women Artists

|

Rania Hassan, Pensive I, II, III, 2009, oil, fiber, canvas, metal wood, Each piece

is 31″h x 12″w x 2-1/2″ It’s currently on view at Greater Reston Arts Center. |

There’s a revival of status and attention given to traditional, highly-skilled arts and crafts made of yarn, thread and materials. “Stitch,” a new show at Greater Reston Arts Center (GRACE), proves that traditional sewing arts are at the forefront of contemporary art, and that fiber is a forceful vehicle for expression. Meanwhile, the National Museum of Women in the Arts puts the historical spin on traditional women’s art in “Workt by Hand,” a collection of stunning quilts from the Brooklyn Museum which were shown in exhibition at their home museum last year.

|

Bars Quilt, ca. 1890, Pennsylvania; Cotton and wool, 83 x 82″;

Brooklyn Museum,

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. H. Peter Findlay, 77.122.3;

Photography by Gavin Ashworth,

2012 / Brooklyn Museum |

Quilts are normally very large and utilitarian in nature. To some historians, American quilts are appreciated as material culture with possible stories of the people who made them, but they also have some vivid abstract patterns and strong color harmonies. Their bold geometric shapes vary and change with different color combinations. Quilting is a folk art since it is a passed down tradition, and the patterns may seem stylized and highly decorative. Yet there is room for tremendous variation, creativity and individual style.

Within the United States there are important regional folk groups whose quilts have a distinctive style, like the Amish quilt, above. Amish designs can have a sophisticated abstraction deeply appreciated during the period of Minimal Art of the 1960s and 1970s. The exhibition outlines distinctions and also shows styles popular at certain times, including Mariners’ Knot quilts around 1840-1860, the Crazy Quilts of the Victorian period and the Double Wedding Ring pattern popular in the Midwest after World War I.

|

| Victoria Royall Broadhead, Tumbling Blocks quilt–detail, 1865-70 Gift of Mrs Richard Draper, Brooklyn Museum of Art. Photo by Gavin Ashworth/Brooklyn Museum. This silk/velvet creation won first place in contests at state fairs in St. Louis and Kansas City. |

, |

|

|

|

|

One beautifully patterned quilt is from Sweden, but the rest of them are made in the USA. The patterns change like an optical illusions when we move near to far, or when we view in real life or in reproduction. There’s the Maltese Cross pattern, Star of Bethlehem pattern, Log Cabin pattern, Basket pattern and Flying Geese pattern, to name a few. The same patterns can come out looking very differently, depending on the maker. An Album Quilt has the signatures of different people who worked on different squares. We know the names of a handful of the quilting artists.

|

Orly Cogan, Sexy Beast, Hand stitched embroidery

and paint on vintage table cloth, 34″ x 34″ |

While most of the quilts featured in the exhibition were made by anonymous artists, the Reston exhibition includes well-known national figures in fiber art, such as Orly Cogan and Nathan Vincent. Cogan uses traditional techniques on vintage fabrics to explore contemporary femininity and relationships. Her works appear to be large-scale drawings in thread. She adds paint and sews into old tablecloths. I loved the beautiful Butterfly Song Diptich and Sexy Beast, a human-beast combination with multiple arms, like the god Shiva. Vincent, the only man in the show, works against the traditional gender role, crocheting objects of typically masculine themes, such as a slingshot.

|

Pam Rogers, Herbarium Study, 2013, Sewn leaves, handmade

soil and mineral pigments, graphite,

on cotton paper, 22″ x 13-1/2″ |

Most “Stitch” artists are local. Pam Rogers stitches the themes of people, place, nature and myth found in her other works. Kate Kretz, another local luminary of fiber art, embroiders in intricate detail, expressing feelings about motherhood, aging and even the art world.

Kretz’s own blog illuminates her work, including many of the pieces in “Stitch. The pictures there and the detailed photos on an embroidery blog display in sharper detail and explain some of her working methods.

Often she embroiders human hair into the designs and materials, connecting tangible bits of a self with an audience. Kretz explains, “One of the functions of art is to strip us bare, reminding us of the fragility common to every human being across continents and centuries.”

Kretz adds, “The objects that I make are an attempt to articulate this feeling of vulnerability.” Yet some of the works also make us laugh and chuckle, like Hag, a circle of gray hair, Unruly, and Une Femme d’Un Certain Age. Watch out for a dagger embroidered from those gray hairs!

|

Kate Kretz, Beauty of Your Breathing, 2013, Mothers hair from gestation

period embroidered on child’s garment, velvet, 20″ x 25″ x 1″ |

|

Suzi Fox, Organ II, 2014, Recycled

motor wire, canvas, embroidery hoop

12-1/2″ x 8″ x 1-1/2″ |

Kretz is certainly not the only artist who punches us with wit and irony, and/or human hair, into the seemingly delicate stitches. Stephanie Booth combines real hair fibers with photography, and her works relate well to the family history aspect alluded to in NMWA’s quilting exhibition. Rania Hassan is also a multimedia artist who brings together canvas paintings with knitted works. In Dream Catcher and the Pensive series of three, shown at top of this page, she alludes to the fact that knitting is a pensive, meditative act. She painted her own hands on canvases of Pensive I, II, III and Ktog, using the knitted parts to pull together the various parts of three-dimensional, sculptural constructions. She adds wire to the threads for stiffness, although the wires are indiscernible. Suzi Fox uses wire, also, but for delicate, three-dimensional embroideries of hearts, lungs and ribcages (right).

There’s an inside to all of us and an outside. Erin Edicott Sheldon reminds us that stitches are sutures, and she calls her works sutras. Stitches heal our wounds. “I use contemporary embroidery on antique fabric as a canvas to explore the common threads that bind countless generations of women.” Her “Healing Sutras” have a meditative quality, recalling the ancient Indian sutras, the threads that hold all things together.

|

Erin Endicott Sheldon, Healing Sutra#26, 2012, hand

embroidery on antique fabric stained with walnut ink |

In this way she relates who work to the many unknown artists who participated in a traditional arts of quilting. Like the Star of Bethlehem quilt now at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the traditional “Stitch” arts remind us to follow our stars while staying grounded in our traditions.

|

| Star of Bethlehem Quilt, 1830, Brooklyn Museum of Art Gift of Alice Bauer Frankenberg. Photo by Gavin Ashworth/Brooklyn Museum |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 9, 2013 | 19th Century Art, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Drawings, Durer, Exhibition Reviews, Jean-Francois Millet, National Gallery of Art Washington, Pastels, Portraiture, Renaissance Art, Watercolor

|

Albrecht Dürer, The Head of Christ, 1506

brush and gray ink, gray wash, heightened with white on blue paper

overall: 27.3 x 21 cm (10 3/4 x 8 1/4 in.) overall (framed): 50 63.8 4.1 cm (19 11/16 25 1/8 1 5/8 in.)

Albertina, Vienna |

The National Gallery of Art is hosting the largest show of Albrecht Dürer drawings, prints and watercolors ever seen in North America, combining its own collection with that of the Albertina in Vienna, Austria. Across the street in the museum’s west wing is the another exhibition of works on paper, Color, Line and Light: French Drawings Watercolors and Pastels from Delacroix to Signac. The French drawings are spectacular, but it’s hard to imagine the 19th century masters without the earlier genius out of Germany, Dürer, who approached drawing with scientist’s curiosity for understanding nature.

|

Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait at Thirteen, 1484

silverpoint on prepared paper, 27.3 19.5 cm

(10 3/4 7 11/16 in.) (framed): 51.7 43.1 4.5 cm (20 3/8 16 15/16 1 3/4 in.)

Albertina, Vienna |

Dürer’s famous engravings are on view, including Adam and Eve, but with the added pleasure of seeing preparatory drawings and first trial proofs of the prints. Some of his most famous works such as the Great Piece of Turf and Praying Hands, are there also. In both exhibitions, as always, I’m drawn to the beauty and color of landscape art, especially prominent in the 19th century exhibition. However, both shows have phenomenal portraits to give us a glimpse into people of all ages with profound insights.

Dürer drew his own face while looking in the mirror at age 13, in 1484. He still had puffy cheeks and a baby face, but was certainly a prodigy. Like his father, he was trained in the goldsmith’s guild which gave him facility at describing the tiniest details with a very firm point. Seeing his picture next to the senior Dürer’s self-portrait, there’s no doubt his father was extremely gifted, too.

|

Albrecht Dürer, “Mein Agnes”, 1494

pen and black ink, 15.7 x 9.8 cm (6 1/8 x 3 7/8 in.)

(framed): 44.3 x 37.9 x 4.2 cm (17 3/8 x 14 7/8 x 1 5/8 in.)

Albertina, Vienna |

In his native Nuremburg, the younger Dürer was recognized at an early age and his reputation spread, particularly as the world of printing was spreading throughout the German territories, France and Italy. We can trace his development as he went to Italy in 1494-96, and then again in 1500, meeting with North Italian artists Andrea Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini and exchanging artistic ideas. Dürer is credited with bridging the gap between the Northern and Italian Renaissance. I personally find all his drawings and prints more satisfying then his oil paintings, because at heart he was first and foremost a draftsman.

Though we normally think of Dürer as a controlled draftsman, there are some very fresh, loose drawings. An image he did of his wife, Agnes, in 1494, shows a wonderful freedom of expression, and affection. He married Agnes Fry in 1494 and did drawings of her which became studies for later works. She was the model for St. Ann in a late painting of 1516 and the preparatory drawing with its amazing chiaroscuro is in the exhibition.

|

Albrecht Dürer, Agnes Dürer as Saint Ann, 1519

brush and gray, black, and white ink on grayish prepared paper; black background applied at a later date (?)

overall: 39.5 x 29.2 cm (15 1/2 x 11 1/2 in.) overall (framed): 64 x 53.4 x 4.4 cm (25 1/4 x 21 x 1 3/4 in.)

Albertina, Vienna |

|

Also on view are Durer’s investigations into human proportion, landscapes and drawings he did of diverse subjects from which he later used in his iconic engravings. We can trace how the drawings inspired his visual imagery. There are also several preparatory drawings of old men who were used as the models for apostles in a painted altarpiece.

|

Albrecht Dürer, An Elderly Man of Ninety-Three Years, 1521

brush and black and gray ink, heightened with white, on gray-violet prepared paper

overall: 41.5 28.2 cm (16 5/16 11 1/8 in.) overall (framed): 63.6 49.7 4.6 cm (25 1/16 19 9/16 1 13/16 in.)

Albertina, Vienna |

My favorite drawing of old age, however, is a study of an old man at age 93 who was alert and in good health (amazing as the life expectancy in 1500 was not what is today.) He appears very thoughtful, pensive and wise. The softness of his beard is incredible. The drawing is in silverpoint on blue gray paper which makes the figure appear very three-dimensional. To add force to the light and shadows, Durer added white to highlight, making the man so lifelike and realistic.

|

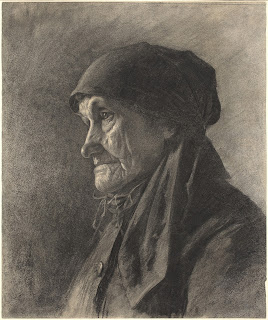

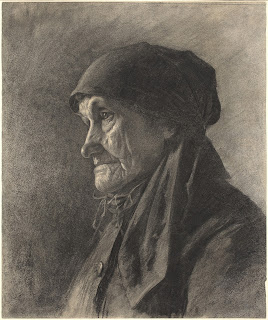

Léon Augustin Lhermitte, An Elderly Peasant Woman, c. 1878

charcoal, overall: 47.5 x 39.6 cm (18 11/16 x 15 9/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James T. Dyke, 1996 |

In the other exhibition, there’s a comparable drawing by Leon Lhermitte of an old woman in Color, Line and Light. Lhermitte was French painter of the Realist school. He is not widely recognized today, but there were so many extraordinary artists in the mid-19th century. What I find especially moving about the painters of this time is more than their understanding of light and color. I like their approach to treating humble people, often the peasants, with extraordinary dignity. Lhermitte’s woman of age has lived a hard and rugged life and he crinkled skin signifies her amazing endurance. We see the beauty of her humanity and the artist’s reverence for every crevice in her weather-beaten skin.

|

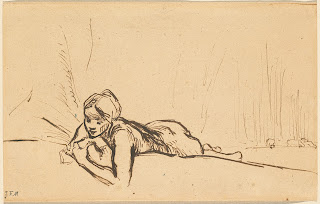

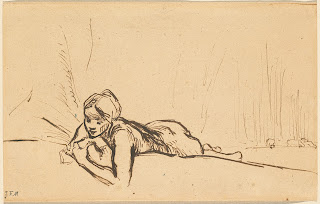

Jean-François Millet

Nude Reclining in a Landscape, 1844/1845

pen and brown ink, 16.5 x 25.6 cm (6 1/2 x 10 1/16 in.)

Dyke Collection |

|

There are many portraits of youth in the French exhibition, too, including fresh pen and inks such as Edouard Manet’s Boy with a Dog and Francois Millet’s Nude Reclining in Landscape, who really does not look nude.

Camille Pissarro’s The Pumpkin Seller is a charcoal without a lot of detail. She has broad features, plain clothes and a bandana around the head. She’s a simpleton, drawn and characterized with a minimum of lines but Pissarro sees her a substantial girl of character. The drawing reminds me of Pissarro himself. He may not be as well-known and appreciated as Monet, Renoir, Degas, yet he was the diehard artist. He was the one who never gave up, who encouraged all his colleagues and was quite willing to endure poverty and deprivation for the goals of his art. Berthe Morisot‘s watercolor of Julie Manet in a Canopied Cradle has a minimum of detail but is a quick expression of her daughter’s infancy.

|

Camille Pissarro, The Pumpkin Seller, c.1888

charcoal, overall: 64.5 x 47.8 cm (25 3/8 x 18 13/16 in.)

Dyke Collection |

Taking in all the portraits of both exhibitions, I’m left with thoughts of awe for beauty of both nature and humanity. The friends I was with actually preferred the French exhibition to the Dürer. There were surprising revelations of skill by little known artists like Paul Huet, Francois-Auguste Ravier and Charles Angrand. The landscapes by artists of the Barbizon School and the Neo-Impressionists, are important and beautiful, but perhaps not recognized as much as they should be. In both exhibitions, we must admire how works on paper form the blueprint for larger ideas explored in oil paintings.

|

Berthe Morisot, Julie Manet in a Canopied Cradle, 1879

watercolor and gouache, 18 x 18 cm (7 1/16 x 7 1/16 in.)

Dyke Collection |

It was a curator a the Albertina who wisely connected a mysterious Martin Schongauer drawing of the 1470s owned by the Getty to a Durer Altarpiece. The Albertina is a museum in Vienna known for works on paper, much its collection descended from the Holy Roman Emperors, one of whom Dürer worked for late in his career. The French drawings come from a collection of Helen Porter and James T Dyke and some of it have been gifted to the National Gallery. They’re on view until May 26, 2013 and Albrecht Dürer: Master Drawings, Prints and Watercolors from the Albertina will stay on view until June 9, 2013.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Dec 5, 2012 | Contemporary Art, Exhibition Reviews, Fiber Arts, Folk Art Traditions, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Women Artists

|

| Photo courtesy of Rachael Matthews from the UK Crafts Council |

“High fiber” usually refers to a type of diet, but High Fiber at the National Museum for Women in the Arts demonstrates how “high art” integrates with the everyday world of a Folk Art. In the multi-media world of contemporary art, Fiber Art has gained recognition as a serious art form over the last fifty years. Like the art of glass making, fiber art was invented milleniums ago for utilitarian purposes. Knitting, sewing and weaving developed to meet basic needs of warmth and clothing, but as soon as pattern and design were involved, the process of making art began.

|

| Knitted objects are often in Matthews’ work |

When the ancient artists/crafters knitted, knotted, wove or stitched to follow patterns or innate designs in their heads, they tied together movements between the left and right hands, bridging the creative left side of the brain with the analytical right side of the brain.

Contemporary fiber art may or may not have definite recognizable patterns and designs, but fiber art by definition is very tactile and textural. It may also be sculptural.

The National Museum for Women in the Arts’ exhibition of contemporary fiber artists, on view until January 6, 2013, features seven contemporary fiber artists, each working in styles completely different from the next one. High Fiber is the third installment of NMWA biennial Women to Watch exhibition series, in which regional outreach committees of the museum meet with local curators to find artists. The NMWA made a final selection of the seven artists representing different states and countries.

Rachael Matthews was a leader in a revival of knitting movement in the UK about 10 years ago. She is co-owner of a knit shop in London, Prick Your Finger, where one is more likely to see objects crafted of yarn, rather than a sweater. In Knitted Seascape, 2004, Matthews used illusionism much the way painters do; her hanging curtains, lace-like and pleated, open onto the seascape seen through a false window. She created depth similar to that in Raphael’s visionary painting. The vigorous texture into those waves, making their foam as real as in a Winslow Homer seascape, is not painted but knitted. Matthews also did a floor sculpture to which an hourglass and skull and crossbones attach. We are reminded of death in A Meeting Place for a Sacrifice to the Ultimate Plan, 2010. Another piece she supplied in the exhibition is a wedding dress, made as a collaborative effort where the individual pieces knit by different women form the whole. Collaboration and connection is certainly a part of emerging trend in Fiber Art.

Louise Halsey, from the Arkansas council, is a weaver, who has spent years studying the ancient art of weaving, while teaching and doing workshops. Her work demonstrates vivid color and technical perfection, but also shares the artist’s own narrative ideas. The four works in this show are images of homes. On her website, she explains, “Recently I have been weaving tapestries using the house as a symbol for what I cherish. These images of houses include placing the house amidst what I see as threats that are present in the environment.” Dream Facade, at right, may warn of being too strongly possessed and owned by vanity, while Supersize My House, 2011, questions the dream of bigger and bigger homes.

Louise Halsey, Dream Facade, 2005

wool weft on linen warf – tapestry technique

The house becomes sculpture in large, colorful constructions by Laure Tixier, from France and representing Les amis du NMWA, are based on architecture from around the world. Like children’s forts out of blankets, architecture meets the basic need for shelter with imagination in design. She stitches the forms out of felt and very large Plaid House reflects the classical architecture of Amsterdam. Smaller houses are also on display and they reveal her domestic interpretations of diverse types of architecture, including that of the future. Tixier clearly has an interest in the symbolism and meaning of architecture in history.

Laure Tixier’s Plaid House , 2008, wool felt and thread, 90-1/2″ x 33-1/2″

Collection of Mudam Luxembourg

Debra Folz of Boston combines sophisticated cross-stitch patterns on furniture and mirrors with a sleek modern look. Her works are a contrast to the homespun beauty of some of the works described above, but she was trained in Interior Design. The threads are small and look mechanical but can have depth, control, color harmony and pattern. Mixing thread with a industrial materials may sound discordant, but this harmony of opposites is beauty!

Debra Folz, XStitch Stool, 2009. Steel base,

perforated steel and nylon thread, 20 x 14 x 12 in

Steel is the canvas for embroidery.

|

| Beili Liu, Toil, 2008, Silk organza,72 x 36 x 8 in |

Homes and their contents give security and comfort, but not all works of art in the exhibition have a domestic meaning. There are sculptural wall hangings and installations in the NMWA’s show. Beili Liu, recommended by the Texas State committee, spun strips of silk, a material traditionally associated with China, her country of origin. For Toil, she burned the edges of silk fabric with incense before winding the strips into the funnel-shaped projections that point off the wall. These forms twist and turn in various directions — like miniature tornadoes — creating paths and shadows on the wall. A variety of beige and brown tones add to the richness of this view. Liu’s larger Lure Series (not on view) installations use thread to recall Chinese folklore, she has that is said her work highlights the tensions between her Eastern origins and Western influences. She bridges these gaps well. In fact, fiber art is all about connecting.

Fiber Art seems to be on the verge of asserting new importance into the world of art. Jennifer Lindsay, one of my former students from the Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art and Design’s Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts, coordinated the public outreach, the design and collaborative installation of the Smithsonian Community Reef. The replica of a coral reef in crochet made expressly for the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s 2010-2011

expressly for the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s 2010-2011 Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef project, is now on view in the Putman Museum of History and Natural Science in Davenport, Iowa, until 2016.

|

| Jennifer Lindsay, Cowgirl Jacket is a memento mori to Frida Kahlo, photo by Judy Licht |

Jennifer also dyes her own wool yarns and uses them to make intricate knitted and crocheted clothing, examples of which are shown here. She calls her cowgirl jacket a memento mori for Frida Kahlo. It uses nearly every knitting stitch available. Note the skeletons which link this design to El Dia de los Muertos. Memento mori is a reminder of death.

|

| Lindsay’s Russian Star, photo by Judy Licht |

Getting back to the women’s museum, in the permanent collection, there are other works of fiber or those that remind us of fiber. On the 3rd floor of the NMWA, Remedios Varo’s Weaving of Space and Time is on loan along with two other works by Varo. The oil on masonite painting uses a symbolic circle to magically pull together the opposites of male and female figures, representing time and space. Within the circle are threads, not real threads but painted threads in light glazes that weave together ideas. Nearby is also a Judy Chicago painting whose circular painted form in acrylic and airbrush resembles the type of patterning with which traditional fiber artist created.

NMWA also has a piece by Magdalena Abakanowicz, one of the best known fiber artists of today. Four Seated Figures are of her recognizable life-size figural types made of fabric. The same, yet different, these abakans are representative the anonymity and uniformity of communist society in Poland, what she has known during the bulk of her life. Born in 1929, to Abakanowicz is accustomed to living in conditions which repressed individual creativity and intellect in favor of the collective interest.

|

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Four Seated Figures, 1974-2002, burlap, resin, metal pedestal

figure: 115 cm, 55 cm, 63 cm pedestal: 76 cm, 47 cm, 23 cm

coll. The National Museum of Women in the Arts |

Finally, we can be reminded of the diverse women came together for their quilt-making art who in a film of 1995 called How to Make An American Quilt, including Maya Angelou, Anne Bancroft, Ellen Burstyn, Alfre Woodard and Winona Ryder. Quilting is one the most lasting forms of Fiber Art, embedded into so many folk art traditions. In the end, the making of a quilt is compared to life: “As Anna says about making a quilt, you have to choose your combination carefully. The right choices will enhance your quilt. The wrong choices will dull the colors, hide their original beauty. There are no rules you can follow. You have to go by your instinct. And you have to be brave.”

It’s with fibers that women can connect and that the women of history are tied to the women of today.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Sep 1, 2012 | 19th Century Art, Art and Literature, Cezanne, Exhibition Reviews, Franz Marc, Gauguin, Giorgione, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Landscape Painting, Matisse, Modern Art, Mythology, Nicolas Poussin

One of the first ‘pastoral‘ paintings(not in the exhibition) was

The Pastoral Concert, 1509, by Titian and/or

Giorgione, originator of the pastoral, where landscape is on par with figures. Shepherds and musicians are frequent in this theme.

Good things always end, including summer and a chance to see how the greatest modern artists painted themes of leisure as Arcadian Visions: Gauguin, Cezanne, Matisse, ends Labor Day.

The exhibition highlights 3 large paintings: Gauguin’s frieze-like Where do We Come From?…, 1898, Cézanne’s Large Bathers, 1898-1905 and Matisse’s Bathers by a River, 1907-17.

Each painting was crucial to the goals of the artists, and crucial to the transitioning from the art and life of the past into the 20th century. These modernist visions actually are part of a much older theme descended from Greece and written about in Virgil’s Eclogues. Nineteenth-century masters were very familiar with this tradition from the 16th-century painting in the Louvre, The Pastoral Concert, by Giorgione and/or Titian. Édouard Manet’s infamous Luncheon on the Grass of 1863 was probably painted to fulfill that artist’s stated desire to modernize The Pastoral Concert. Those who think artists throw away tradition, think again; the greatest artists of the modern age did not.

Arcadia was originally thought to be in the mountains of central Greece. Virgil described a place where shepherds, nymphs and minor gods who lived on milk and honey, made music and were shielded from the vicissitudes of life. With its promise of calm simplicity, Arcadia was a place of refuge. Renaissance scholars writers and painters re-descovered it; Baroque painters developed the theme further, and 19th century artists glorified it because the Industrial created yearnings for a simpler life. (Musée d’Orsay in Paris has a small focused exhibit on Arcadia at the moment.) Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem of 1876, An Afternoon of the Faun, had this theme, too, and was followed by Claude Debussy’s musical interpretation after that poem.

But, even Virgil had warned, that things are not always as they seem. The exhibition’s signature pieces by Gauguin, Cézanne and Matisse reflect harmonious relationships between humans and nature, but tinged with loss. The best of Arcadian visions give equal importance to figures and landscape, as these artists do. Other 19th century painters, whose work is shown for comparison, include Corot, Millet, Signac, Seurat, and Puvis da Chavannes. It is interesting that the museum did not include Auguste Renoir’s Large Bathers, 1887, in the PMA’s own collection, probably because that idealized scene does not have anything foreboding.

Paul Gauguin, Where do we come From? Who Are We? Where Are We Going?(detail of left side), 1898

From the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is so large that it must be seen in real life.

Artist Paul Gauguin escaped France and settled in the the south seas, Tahiti, where he searched for his version of Arcadia. It was the first time I had seen Gauguin’s Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going? No reproduction does justice to its color, details and beauty. Twelve five feet wide and four feet high, it must be seen in person to adequately “read the painting.” Composed of figures familiar from other Gauguin paintings, this allegory makes us think deeply about the meaning of life via Gauguin’s favorite figural types, the women of Tahiti. He depicts youth, adulthood and old age and treats each phase as a moment of discovery and passing to the next, but we may end up with more questions than answers.

Paul Cézanne, The Large Bathers, 1898-1906, Philadelphia Museum of Art, is the

culminations of many studies he had been doing of bathers since the 1870s.

The acoustical guide to the exhibition quotes Paul Gauguin who said that Paul Cézanne spent days on mountaintop reading Virgil. Cézanne’s soul was always in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence and the connection to that past was in his blood, coming from a very classical childhood education of Latin and Greek and hiking through old Roman paths with friend and future novelist, Émile Zola. Even though the bathers have no sensuality, Cézanne’s Large Bathers is a painting which gives exquisite beauty to its concept. To me, it stands out as the most important painting in the show. An article links Cézanne to thoughts of death, Poussin and several poets who wrote of the territory surrounding Aix as Arcadia. This painting is perhaps the most Arcadian modern painting of the exhibition, although there are no shepherds, no musicians and no men. While it picks up the dream of humankind living simply in nature, under its beauty and its bounty, one woman points to the river, suggesting a place where these complacent bathers will ultimately go.

The design of The Large Bathers perfectly balances traditional space and compositional structure with the goals of modern art. I always knew how much I loved this painting, but now I know why. The exhibition gave me much new insight and appreciation to fill an entire blog about this painting. Matisse’s painting is in the same large room of the exhibition, but the message is less subtle.

Matisse spent ten years revising this painting, 8’7″ by 12’10” Art Institute of Chicago

He completed Bathers by a River around 1917

Bathers by a River is also very large and, as expected, even more abstract. Matisse worked on the painting for 10 years and changed it, as his ideas and conceptions changed. Noticeable is the lack of color and empty features of the faces. He paints verticals, a suitable balance to the curves, but a snake appears in front and in the center, which can be seen as a dire warning. World War I was happening at the time he finished it. His earlier paintings of bathers were far more joyful and colorful.

Henri Rousseau, The Dream, 1910, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

is approximately 6’8″ x 9’9″

It was a complete surprise to see Henri Rousseau’s The Dream, also a very large painting. The tropical landscape with an elephant and lions is included in the same room of monumental paintings. Rousseau drew exotic plants in the botanical gardens of Paris and he painted them in a simplistic style with unexpected, evocative juxtapositions. He was a visionary before the Surrealists. His woman reclines in a traditional pose on a seat-less sofa, as a dark-skinned horn player and jungle animals appears. Music, repose, luxury of nature are typical Arcadian themes, and it is a joy to see it in the same room with the three signature paintings of the exhibition.

Nicolas Poussin, The Grande Bacchanal, c. 1627, from the Louvre, Paris

To understand all these connections, the curator included a painting by the most representative painter of the Arcadian tradition, Nicolas Poussin. (New York’s Metropolitan Museum hosted an exhibition, Poussin and Nature: Arcadian Visions, 4 years ago.) Poussin was a Baroque artist who was thoroughly engrossed in a classical style with themes taken from ancient writers. His painting The Grande Bacchanal, 1627, on loan from the Louvre, has beautiful women, musicians, a Silenus and even baby revelers, with darkess approaching the landscape. Each of the early modern artists featured in the exhibition were familiar with Poussin’s style and sources, as well as Watteau and Boucher who painted pastoral themes in the 18th century.

Matisse’s early Fauvist paintings, Music and The Dance, are abstract and modern but thoroughly a part of the pastoral tradition. Athough the exhibition does not show any of the colorful compositions Matisse did in the first decade of the 20th century, those paintings have tons of color and are steeped in the pastoral tradition. (I’ll need to take trip to Philadelphia to see the Barnes Collection with another large version of Cézanne’s Bathers and Matisse’s famous The Joy of Life.)

A sketch of “Music” from MoMA links back to Poussin’s The Andrians, with dancers, a lounging woman and a violinist. This painting is not in the exhibition..

Quotes from the poet Virgil’s pastoral literature line the walls. We witness how various artists of the 19th and 20th centuries interpreted his poetry in drawings, paintings, etchings and illustrated books. The exhibition ends with Picasso, Cubists, Expressionists and little-known Russian painters of the 20th century. Although not always inspired by Virgil or Ovid, these paintings can be linked to the desire for a bucolic life of simplicity and harmony in nature.

I was awed to see the Robert Delaunay’s City of Paris, 1910-12. Delaunay famously painted the Eiffel Tower in a Cubist jumble of colors and shifting perspectives. That symbol of modernism was only a little more than 20 years old at this time. This giant canvas of Paris also has three large nudes. They are the Three Graces, just as Botticelli and Raphael had painted them. Delaunay’s vision of Paris includes the past and the present, but the nudes of the past are actually seem more central to this composition of shifting triangles, circles and planes of colors. If anything, Cubism reminds us of life’s impermanence.

Robert Delaunay, City of Paris, 1910-12, is 8’9″ x 13’4″

Finally, at the end we see

Franz Marc’s Deer in Forest, II, from the Phillips Collection. Here the humans are gone and only animals are in the forest. The exhibition is very thoughtful and reflective, and I thank Curator Joseph Rishel for giving us so much to ponder. It is one designed not only to make us only look art more closely, but we must also think more deeply.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Aug 20, 2012 | African-American Art, Exhibition Reviews, Modern Art, Photography, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Sam Gilliam, The Petition, 1990, mixed media

Smithsonian American Art Museum’s exhibition, African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, the Civil Rights Era and Beyond gives a broad overview of 43 artists whose work spanned 8 decades of the 20th century. Over 40 photographs, as well as paintings, give a provocative picture of urban and rural life during the Depression, the age of segregation and the Civil Rights and later. Although there is some overlap with other 20th century art movements, the exhibition is mainly art focused on African-Americans and their lives. Both abstract and figural paintings are included, but also sculpture by Richard Hunt, Sam Gilliam, an important recent figure in the art scene of Washington, DC. The artists come from the South and North, with a large number from urban areas of Detroit, New York, St. Louis, Baltimore and Washington, DC.

Detroit artist Tony Gleaton recorded his travels to Nicaraguain in Family of the Sea, 1988, from the series Tengo Casi 500 Anos: Africa’s Legacy in Central America, above. Roy De Carava was a New Yorker whose photos capture aspects of city life as in Two Women Manikan’s Hand, 1950, printed 1982, on right. (gelatin silver prints)

The portraits give impressive concentrated views of individual personalities, particularly by Tony Gleaton and Earlie Hudnall, Jr. I especially liked the photographs of Ray DeCarava, for the artistic compositions with interesting value contrasts. Although the portrait photography is very interesting, I’m partial to DeCarava’s staged compositions which look like film stills.

Ray DeCarava, Lingerie, New York, 1950, printed 1982, gelatin silver print, left.

Gleaton’s works are part of series photos, such as Africa’s legacy in Central America. But there is also a series from the WPA (Works Project Administration of the 1930s, part of the New Deal. Robert McNeill ‘s several photographs include those from his project entitled, The Negro in Virginia which has both interesting portraits and slices of life. The art of photojournalism really began at this time, during the 1930s.

The contrast of black and white photography works well exhibited next to bold, colorful works of art by the Harlem Renaissance artists, such as Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden, who worked with collages. Bearden, Lawrence, as well as Lois Mailou Jones and Norman Lewis, are among the most important painters who contributed to the artistic life of Harlem in the 20s and 30s. The Harlem Renaissance also produced writers, musicians and poets such as Langston Hughes.

Community, by Jacob Lawrence is a gouache of 1986.

It is a study for the mural of the same name in Jamaica, New York

Lawrence lived until 2000 and spent his last 30 years as a professor at the University of Washingon in Seattle. The exhibition has both an early and a late work. Lawrence maintained a similar style in the later work, always influenced by colors in Harlem which he said inspired him. Lawrence’s most famous works are the series paintings, The Migration Series, half of which is in Washington’s Phillips collection, and the Harriet Tubman series and the Frederick Douglas series at the Hampton University in Hampton, Virginia, where another large collection of African-American art is kept.

Charles Searles’ Celebration is an acrylic study for a mural painting

in the William H Green Building, Philadelphia, made in 1975

Charles Searles was from Philadelphia and the Smithsonian’s Celebration is actually a study for a mural done in the William H Green Federal Building in Philadelphia. Likewise, Community is a study for a mural Lawrence did in Jamaica, New York, 1986. It evokes a spirit of togetherness and cooperation.

Norman Lewis, Evening Rendezvous, 1962

Abstract works may actually be visualizations with other meanings. Norman Lewis’s Evening Rendezvous of 1962, is an abstract medley of red white and blue, but the white refers to hoods of the KluKluxKlan and red to fires and burnings. Not all is innocent fun, but Enchanted Rider, done by Bob Thompson in 1961 is more optimistic. The rider may actually be a vision of St. George who triumphed over evil and is a traditional symbol of Christian art.

Enchanted Rider by Bob Thompson, 1961

Though the exhibition is somewhat historical, it wants the viewer to judge each piece on its own merit, and to see it as a unique expression of the individual artists. There is not a heavy emphasis on chronology or history. Lois Mailou Jones is one such personal, but symbolic artist who picked up ideas from living in Haiti and traveling to 11 African countries. In Moon Masque, 1971, pattern, fabric design and African rituals are evoked. I like the color in most of these paintings and the celebration of life so vividly expressed in these works.

Lois Mailou Jones, Moon Masque, 1971

The Smithsonian American Art Museum has the largest collection of African-American Art in any one location, but this exhibition is only a portion of their collection. Some modern masters, such as Elizabeth Catlett, Faith Ringgold and Perry James Marshall, are not included in this showing. After the exhibition closes in Washington September 3, it will travel to museums in Williamsburg, Orlando, Salem, MA, Albuquerque, Chattanooga, Sacramento and Syracuse for the next 2-1/2 years.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments