A Wonderful Oddball Artist: Piero di Cosimo

|

| Piero di Cosimo, Giuliano da Sangallo and Francesco Giamberti. The two-part painting was on loan from Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum recently. |

An exhibition of Renaissance painter Piero di Cosimo’s recently closed at the National Gallery in Washington a few months ago, and it’s taken me awhile to develop and express my understanding of him. Piero di Cosimo: The Poetry of Painting in Renaissance Florence continues a the Uffizi Gallery with a slightly different body of works in Florence, until September 27. It’s an interesting look at this quirky painter, someone who was living and working at the same time as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.

|

| Piero di Cosimo’s Allegory, is part of the National Gallery’s own collection. It is seen as an allegory of overcoming one’s animal nature. |

Many of my students who wrote reviews of the exhibition dealt entirely with his religious paintings, the subjects you expect to see most often in Renaissance art. Like most Renaissance artists, Piero also did portraits. Some portraits, especially the diptych of Giuliano da Sangallo, architect, and Francesco Giamberti, musician, (above) are fabulous. Each part of the diptych is a separate window view of the subjects stand in front of deep landscape space. The colors radiant, the textures exquisite.

However, Piero is best known for his paintings of mythological allegories. Allegory in the National Gallery, left, is usually interpreted as a classical story of the choice between good and evil, also called The Dream of Scipio. There’s a winged female figure taming the wild horse. The animal is a reminder of the bestial side of nature. (Most men need to be tamed by women.) The half-human mermaid on bottom is swimming to the right.

|

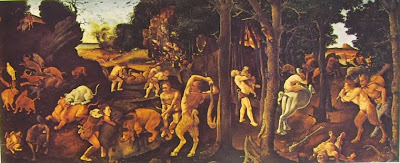

| Piero di Cosimo, The Hunting Scene, c. 1510, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

To me, his paintings are complex allegories of interrelated themes. Even the religious paintings carry the same themes as the mythological paintings. He’s very interested in man’s bestial nature, the choices between good and evil and the possibilities for transformation (redemption). Of interest are two scenes from the Metropolitan Museum. The Hunting Scene, (above) is web of animals fighting men and satyrs. It looks like two satyrs in front right have clubbed a man to death– a man who is radically foreshortened and ghostly pale. It is brutal, like The Battle of Ten Naked Men. According to the Metropolitan Museum, Piero was inspired by Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura.

|

| Return from the Hunt (detail) Metropolitan, NY |

Two rooms at the National Gallery were devoted to the mythologies, which I find to be his most imaginative and interesting works. Giorgio Vasari, the first Italian Renaissance art historian, writing after Piero died, explained the artist by saying,”It pleased him to see everything wild like his own nature.”

On the other hand, I see that Piero as relating his depictions primeval themes to Christianity. The sequel to the brutal hunting scene, Return from the Hunt, has a the detail (right), a man sitting in a tree that resembles the cross, and another man making or carrying a wooden cross like Simon. Is it somehow connected to Jesus’ crucifixion, even if Jesus and Simon aren’t there?Couples are falling in love. It would seem that Piero believes that even the wildest of men can be redeemed and overcome their animal nature.

It was common for Renaissance artists to do graphic compositions to show off their knowledge of one-point linear perspective. The Building of a Palace is Piero’s showpiece of perspective. This interesting demonstration of building methods has multiple activities going on at once. Another wooden cross is visible in the upper right, attached to a piece of machinery in front of the grand palace. He repeats the cross in what appears to be a secular scene, somewhat like the way Dutch artists of the 1600s put in their reminders of death and redemption. Surely the Christian message was important to Piero no matter how secular or pagan he seems.

|

| Piero di Cosimo, The Building of a Palace, 1515-20, Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida |

When Piero painted Perseus and Andromeda, a classical tale from Ethiopia, he picked up a theme not so different from the familiar Christian story of St. George and the Dragon.

|

| Perseus and Andromeda, 1510 or 1513, Uffizzi, Florence |

The National Gallery’s painting, The Visitation with St. Nicholas and S. Anthony, is one of Piero’s most famous paintings. Vasari describes the reflections on the balls of St. Nicholas as a reflection of the “strangeness of his brain.” After his teacher Cosimo Roselli died, Piero shut himself up and led a life less man than beast, according to Vasari. “He would never have his rooms swept. He would only eat when hunger came to him, and then only eggs. He boiled 50 eggs at a time, at the same time he boiled his glue for paint.”

|

| The Discovery of Honey, from the Worcester Art Museum |

Vasari further described Piero’s eccentricities. He was deathly afraid of lightning. Is it the real Piero, or something Vasari arrived upon by hearsay or by his own deduction? We will never know. “And he was likewise so great a lover of solitude, that he knew no pleasure save that of going off by himself with his thoughts, letting his dance roam and building his castles in the air.” The small mythological paintings, like The Invention of Honey, show his greatest gift as an artist: the ability to tell a story with allegorical content. Along with this storytelling ability, he had a wonderful capability of creating panoramas with perspective and integrating the figures into nature.

|

| Piero di Cosimo, Vulcan and Aeolus, c. 1500, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa |

Piero is better at painting panoramic allegories than painting figures on a larger scale. Sometimes the anatomy is weak and his foreshortening is inaccurate, as in Vulcan and Aeolus. Yet the painting is enchanting and brings us into a dreamworld where an unexpected mix of events takes place. A Dutch painter who lived at the same time, Heironymous Bosch, also painted giraffes he never may have seen. Like Bosch, he’s an ancestor of Surrealists. What was he thinking?

|

| The Myth of Prometheus, c. 1515, Alte Pinakothek, Munich |

|

| Madonna with Jesus, St. John the Baptist, Sts. Jerome and Bernard of Clairvaux |

A round tondo painting by Piero, Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist, St. Bernard of Clairvaux and St. Jerome, is lovely. It also has narrative dramas to illustrate the human struggle between good and evil in the middleground. St. Jerome is beating his chest to ward off temptation. The lion is shown with him, because St. Jerome tamed a lion. Behind St. Bernard, a devil is tied to a column, symbolizing the conquest of temptation. Another gorgeous religious painting tondo painting is in Tulsa, where the child Baptist gives his lamb to Baby Jesus.

|

| Simonetta Vespucci, not in the NGA show Musee Conde, Chantilly France |

The National Gallery show had exquisite paintings of Saint Mary Magdalene and St. John the Evangelist that looked like portraits. Their iconographic details show that Piero was influenced by the details and symbolism of Flemish artists. St. John holds a chalice with a snake a symbol attesting to his faith when the Romans asked him to swallow poison. Piero di Cosimo’s most famous portrait, a painting of the beautiful Florentine icon Simonetta Vesupucci, who died too young, was not in the National Gallery exhibition. Piero painted her as if bitten by an asp, like Cleopatra, on left. Again, he used the theme of snakes, which would seem to fit with his

His bacchanalian scenes had “strange fauns, satyrs, sylvan gods, little boys and bacchanals, that is is of marvel to see the diversity of the bay horses and gameness, and the variety of goat like creatures,” describes Vasari. There is a “joy of life produced by the great genius of Piero. There’s a certain subtlety by which he investigates some of the deepest and most subtle secrets of Nature, but only for his own delight and for his pleasure in art.”

|

| detail the Invention of Honey |

Vasari wrote more about Piero other artists who are considered even greater painters, namely Giorgione and Correggio. Vasari had a Florentine bias, and Piero was from Florence. Vasari also wrote, “If Piero had not been so solitary, and had taken more care of himself, he would have made known the greatness of his intellect in such a way that he would have been revered. By reason of his uncouth ways, he was rather held to be a madman.”

Piero was a wonderful eccentric who painted many imaginative and poetic mythologies. What links him to the best of the Renaissance is his lush colors, his landscapes and deep perspective. Some of his work is excellent but others stand out for their uneven quality. What breaks the mold for this time is when his mythologies reveal mankind’s delightful, bestial nature. Like the mannerist images Arcimboldo came up with later in the 16th century, his paintings teach us about the dark side of our human nature. In fact, his knarled branches look much like Arcimbolodo’s portrait of the The Four Seasons in One Head.

Recent Comments