by Julie Schauer | Sep 27, 2013 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Architecture, Erechtheion, Greek Art, Parthenon, the Acropolis

|

The Erechtheion is an Ionic building, with its porches going in different directions.

It commemorates the founding of Athens, with the contest between Athena and Poseidon |

Glistening white marbles which is seem to grow out of the hill form the picture on my mind of the Athens’ Acropolis, from what I’ve seen in textbooks. The city’s highest hill has been a wonder to the world for 2500 years, and a symbol of Greek civilization since ancient times.

|

One climbs the hill to get to the Propylaia, monumental gateway to the Acropolis.

A wide opening in the center allowed horse-drawn chariots

to enter. This view is from inside the hill. |

|

Although the Parthenon is

Doric, this column on the

ground was Ionic |

Yet, at any given time, so much on the Acropolis is in the process of restoration, covered up by scaffolds. I was there on the first day of June, which, unusually, was not a sunny day.

|

A view of the Acropolis ruins leads to another hill, capped

Athens Tower |

I was surprised to see that there are as many stones on the ground as there are against the skies. It appears that the archaeologists have carefully arranged, catalogued and labelled the stones with numbers to fit them into a puzzle which could locate and determine their placement in the past. I must confess to be a lover of ruins who finds them very dramatic and sees great beauty in their fallen state. Close-up views reveal the artfulness that goes into creating fine decorative designs.

Of course, the Parthenon is the best known, most beautiful and most perfectly proportioned of all Greek temples. Most of the building’s west end was hidden from view, while I was there. From a few angles it’s possible to see a good deal of its former glory.

|

| East end of the Parthenon from inside of the Acropolis |

|

The pediment on the left side of the east end, the heads of

horses pulling the chariot of the sun and a reclining god

are visible. These plaster casts replace the Elgin marbles. |

Unfortunately, the center of the Parthenon blew up and was lost for good in 1685, when the Ottoman Turks were using it as an arsenal and a Venetian cannon hit it. In 1804, Lord Elgin, British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, took most of its marble architectural sculpture and brought it to his home in Scotland. When he financial problems, he sold these originals, called the Elgin Marbles, to the British Museum, where they remain today. In some accounts, the marbles were being damaged and at risk of more damage under the Ottoman rule of the time.

However, there are plaster casts on the building, including sculpted horses and a reclining god (Dionysos or Heracles) on left side of the east pediment. These gives a great impression of how the the sculptures fit in under the roof. Replicas of the rest of the sculpture are on display at the New Acropolis Museum in Athens, completed in 2009. The museum’s display reveals fairly well how the large sculptural program related to the architecture.

|

Above a triglyph is a horse’s head on

the opposite side of the pediment

|

I was surprised to find out that a few of the

original square relief sculptures, called metopes, are actually in the Acropolis Museum.

One of these reliefs is particularly beautiful: Hebe and Hera, mother and daughter who sat among the gods and goddesses deciding the outcome of the Trojan War. Despite all the damage, the panel was recently restored. The drapery of the seated goddess, Hera, is so beautiful that we can sense the distinct folds of an undergarment as well as the outer clothing. Experts think that the Parthenon’s chief sculptor, Phidias, did this panel.

|

The Metope of goddesses Hebe and Hera

are among 4 metopes still in Athens |

|

|

There’s so much more history of construction and destruction. The classical building of 442-432 is actually a replacement for the earlier temple to Athena which was burned by the Persians in 480 BC. Many fine statues of young women (kore, called korai, plural) and young men (kouros, called kouroi, plural), which were buried after the Persian pillage, are on display at the museum. Besides the elegant Peplos Kore, there are many other less famous votive statues of women from the Archaic period. Despite the archaic stiffness of many of these sculptures, they are extremely beautiful. I also appreciated the beauty of the relief statues of Nike (victory) figures from the balustrade which had surrounded the Temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis, built after the Parthenon.

|

| The modern, recently-built Acropolis Museum, is set on an angle, but in an axis facing the Parthenon. The Theater of Dionysos, from the 4th century BC covers the hill, between the Parthenon and Acropolis Museum. |

We can see more of the Erechtheion, an unusual temple formed with slender porches reaching out on three different sides. Because of its tall, Ionic columns and the Porch of the Maidens, I found the Erechtheion the most impressive of all buildings on the Acropolis. The caryatids are replacements for the original statues.

|

The Erechtheion is an Ionic temple. Its decorative

details contrast with the simple Doric columns of the other structures |

The original statues can be seen from all sides in the new Acropolis Museum. A trip to that museum is a must for understanding the many stages of construction and destruction on the Acropolis, and for understanding the many building programs of the Acropolis. The Athenians had begun building their temple around 490 BC, before the Persians destroyed it. However, there are sculptures reflecting at least two even earlier temples to Athena, one from about 570 BC, and another dating around 520 BC. The stones of one of these temples are beneath the Erectheoion. Construction and destruction were constants in the lives of the ancient Greeks.

|

A view behind the Porch of the Maidens over to the long side of the Parthenon

reminds me that the Erechtheion stands over the stones of a giant Archaic temple,

an earlier templet to Athena, |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Sep 15, 2013 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Architecture, Greek Art, Knossos, Mythology

This summer I finally had the opportunity to go to Greece and see the sprawling Palace at Knossos. Actually, it’s not certain if this site was a palace, administrative center, giant apartment building, religious/ceremonial building, or all of the above. Yet it is so huge that, when discovered in 1900, archeologist Arthur Evans certainly thought he had found a true labyrinth where the legendary King Minos lived and kept his minotaur. The name Minoan for the Bronze Age people who lived in Crete from about 2000-1300 BC has stuck.

|

Covering 6 acres, the palace of Knossos and the surrounding city may have

had a population of 100,000 in the Bronze Age |

According to legend, the king of Athens paid tribute to King Minos by sending him 7 young men and young women who were in turn fed and sacrificed to the half-man, half-bull minotaur. Eventually, with the aid of Minos’ daughter and the inventor Daedalus, Theseus carried a ball of thread to find his way out and to slay the beast.

Although the art at Knossos doesn’t play out the precise myth, carvings and paintings found there involve imagery of bulls. Acrobats jumped and did flips over the animals’ horns, perhaps part religious ritual. It must have been an exciting but highly dangerous sport, and it’s easy to understand that as the story changed over time, later generations would envision a bull-headed monster in a spooky maze.

|

The palace at Knossos is on the hillside, about 5 kilometers from the sea. It was never fortified

Other, smaller palaces have been uncovered on the island. |

Could a prisoner escape without Theseus’ clever trick? Three or possibly four entrances to the palace are off-axis and may have appeared entirely hidden. The building also had windows, light wells, air shafts and ventilation. It was an engineering marvel. No wonder its architect Daedalus became a god to the Greeks. When I was there, it not only felt like a “labyrinth,” but also like “babel.” Its the only place I’d ever been where so many different, unfamiliar languages were being spoken at once. Despite the number of people, it never felt too crowded, because the palace covers six acres.

|

The downward taper of Minoan

columns is unusual but may have

religious significance. The capital

resembles the cushions of Doric

columns of Greece 1000 years later |

The building runs over 5 levels of twists and turns, on the hillside, not on top of a hill. It had 1300 rooms at one time and could have housed as many 5,000 people. There’s a large central courtyard, perhaps where crowds observed the bull-leaping sports. At least four other ancient maze-like palaces have been excavated on other parts of the island, but none as large as Knossos. It is thought that only 10% of Minoan Crete has been excavated and that bronze age Crete had 90 cities. I remember reading that Knossos had a population of at least 100,000 people around 1500 BC. Minoans traded with Egypt and Mesopotamia. Archaeologists have uncovered a Minoan colony in Egypt, Tel-el D’aba, and at Miletus in Turkey.

|

The North Entrance has a restored

fresco of a bull. Minoans were probably

the first to paint in fresco, on wet plaster |

Evans spent 35 years digging, researching and restoring the Palace of Knossos. The restoration reveals the Minoans’ unusual, downward-facing columns, with the narrowest parts on bottom. The earliest builders used the cypress tree and turned it over, so it wouldn’t grow.

There were both small frescoes and life-size frescoes, most of them now in the Archeological Museum in Heraklion, including the bull-leaping fresco. Since Egyptians painted in secco, on dry plaster, it’s believed that Minoans invented the fresco technique of painting on wet plaster. Colors such as blue, red and yellow ochre are very vivid. Generally Minoans painted with a freer and more organic style than the artists of Egypt and Mesopotamia, and often had more naturalistic depictions. However, whenever men or women are found marching with erect stiff postures, it’s conjectured that they functioned as priests and priestesses partaking in the religious rituals. There’s a famous bull-leaping fresco in the local museum.

|

| La Parisienne from Knossos |

|

|

|

Archeologists of today would not take as much liberty and restore as extensively as he did. While Evans pieced together restorations of the palace based on the remnants and shards, he also used his knowledge to restore what is missing. Personally I appreciate that his reconstruction fills in the blanks for us, giving an idea of the size and grandeur of the palace. Also, there’s a great deal to speculate as to what it may have been like to live there. It seems that grains, wine and olive oil may have been milled and pressed at the palace, and also stored in huge pithoi (giant vases) under the floor.

The word labyrinth originates from the labrys, a double-axe related to the double horns of the bull. The language used at the time the first palace was built, around the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, has not yet been deciphered. A second language which appeared at Knossos after mainland Greeks took over the palace after 1500 BC has been translated and is related to the classical Greek language

|

The life-size Prince of Lilies was thought by

Archeologist Arthur Evans to be a priest.

Lilies are common in Minoan imagery. |

All the inscriptions on cylinder seals are commercial records and inventories. Besides myth, the art and artifacts are the best way to figure out the story of these people. Only about 10 percent of the ancient Minoan sites have been excavated. Although the contents of the Archeological Museum of Heraklion, near Knossos, is well known and published, the beautiful pottery and artifacts from the museum of Chania, Crete’s next largest city, have not been published. Getting outside of the cities and into the countryside leaves the impression that the rural life really hasn’t changed too much in 1000 years.

|

The grand staircase at Knossos spans 5 levels. The layout of rooms is organic around a

central courtyard. What seems to be a haphazard arrangement may reflect

building and rebuilding after earthquakes. |

Certain things that date to the Mycenaean takeover of the palace include the Throne Room. Amazing, when the room was discovered, the gypsum throne was intact. Evidence points to the suggestion that the palace had to be abandoned all of a sudden, because of a fire, natural disaster or invasion. Even if this culture eventually went into oblivion for a few hundred years, when the Greek culture re-emerged around the 8th century BC, the Greeks culture retained so much of the Minoan heritage in its art and myth. The myths of the minotaur, Minos, Europa, Theseus, Daedelus and Icarus involve Crete, but so does the story of Zeus who was said to be born in Crete.

|

The Throne Room was found with oldest throne in

Europe, dating to Mycenaean occupation of Crete, around

1450-1400 BC. Evidence shows people had fled suddenly. |

Knossos has a theatre right outside the palace. Performances took place at the bottom of two seating areas set perpendicular to each other, rather than at the end of curved seating area as in later Greek theaters. The ancient Minoans also gave the world two important inventions, indoor plumbing and the potter’s wheel. Wouldn’t it be something if some of the first great Greek literary masterpieces also had an origin here, 1000 years earlier?

Occupation of the palace ended sometime between 1400 and 1100 BC. In the classical era Crete was never as important as Athens, though it is clear that much of what formed later Greek culture came from Crete. A settlement re-emerged in Knossos during Roman times, but during the Middle Ages the population shifted to the city of Heraklion, about 4-5 miles away.

|

| An area outside of the palace has two sets of seats set at a perpendicular angle. Acoustics indicate it was a theater. |

|

|

|

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 5, 2012 | Ancient Art, Exhibition Reviews, Greek Art, Memorials, Renaissance Art, Sculpture, The Middle Ages

An exquisite of exhibition “mourning” statues at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, have a beauty and realism that give us something to cry about, a phrase Michelangelo used to describe Flemish painting.

In the 15th century, Flanders was ruled by the Duke of Burgundy and similarities to the Flemish style of painting can be are apparent in the style of sculptors Jean de la Huerta and Antoine de la Moiturier. They learned their art from the great Claus Sluter, a Netherlandish sculptor who worked in Burgundy. The Dukes of Burgundy had one of Europe’s richest courts, in rivalry with the King of France to the west and Holy Roman Empire to the east.

The 40 statues line up as if in a funeral procession. At the exhibition, viewers have a chance to see the statues in more completeness and in a more realistic way than in the location they were originally placed, below the bodies of Duke John the Fearless (Jean sans Peur) and his wife, Marguerite. In the current display, the alabaster figures are seen as they move in space, without the elaborate decorative Gothic frames that confine them. They represent the clergy and family members who had been part of Jean the Fearless’ funeral procession in 1424. The statues are on loan from Dijon, France, while the Musee des Beaux Art is undergoing renovation.

Cowls and hoods identify these figures as mourners in the funeral procession. They are alabaster white with details such as books and belts painted. Larger effigies of the duke and duchess were painted in bright colors to look real.

Cowls and hoods identify these figures as mourners in the funeral procession. They are alabaster white with details such as books and belts painted. Larger effigies of the duke and duchess were painted in bright colors to look real.

Like Rogier van Weyden or the

Master of Dreux Budé , these sculptors drew on both realism and emotionalism in a style that is on the cusp between the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The figures are white with a few painted color details, although mourners and even horses, in the funerary procession actually wore black, hooded robes. A tomb of Philippe Pot, Seneschal of Burgundy, from about 1480 has life-size, hooded black figures which hold up the tomb and give an even more realistic version of a funeral.

Life-sized, hooded, black pallbearers were carved anonymously c. 1480 for the tomb of Philippe Pot, Seneschal of Burgundy. They have a greater sense of actuality but less individual, emotional pathos of the group in traveling exhibition.

Life-sized, hooded, black pallbearers were carved anonymously c. 1480 for the tomb of Philippe Pot, Seneschal of Burgundy. They have a greater sense of actuality but less individual, emotional pathos of the group in traveling exhibition.The small white, alabaster figures, however, are full of passionate emotion, and they move into a a variety of different positions. Their angular cuts of drapery are Gothic in style, but when seen in the round, as on display now, the statues have a 3-dimensional spatial conception of the Renaissance. Fortunately the artists carved them in the round, even though they are not seen this way in the Gothic niches underneath the life-sized, reclining duke and duchess. (In 1793, French revolutionaries damaged the effigies of the duke and duchess who represented the repression of the aristocracy, but left the mourners largely unharmed.)

The statuettes are part of the funerary sarcophagus of Jean sans Peur and Marguerite of Bavaria in the fine arts museum of Dijon. The small mourners walk in a funerary procession but are covered by gothic canopies.

These figures call to mind all the mourning figure in art history who accompany the processions and burials of important historical people, and remind us of the processions like those of Roman emperors. Certainly “mourners” were part of the history of art going back more than 5,000 years. However, I couldn’t think of any mourners from early Medieval art because the Early Christians felt death as triumphant and not a matter of earthly pain.

Although the Burgundian court was probably aware of ancient Roman sarcophagii depicting mourners in the funerary procession, the classical Greek-style Sarcophagus of the Mourning Women has a comparable format. This coffin of c. 350 BC was for a king of Sidon, Lebanon, and the women on bottom were probably part of his harem. Each mourner is carved in relief, standing separately between half-columns, while a chariots travel in a frieze above, perhaps the funerary procession or the rulers trip into afterlife. The women twist and  turn and cry to show their various expressions of grief after the death of a leader. As usual, these mourners serve a god-like ruler, not ordinary citizens.

turn and cry to show their various expressions of grief after the death of a leader. As usual, these mourners serve a god-like ruler, not ordinary citizens.

Eighteen women adorn the bottom of a sarcophagus of c. 350 BC, on view at that archeological museum in Istanbul

Early Greek funerary art attempts to show profound emotion. Both the ancient Greeks and Egyptians had elaborate burial ceremonies for their heroes or rulers that could last weeks or months. Mourners accompany pharoahs in their tombs, as the women below.

To the right, female “professional” mourners with raised arms who accompanied the great Ramses in his funerary procession are painted in his tomb.

Detail from a Greek vase in the Metropolitan Museum of Art has rows of mourning figures on either side of the funerary bier. Similar vases come from a cemetery in Athens and they date to 800-700 BC.

The lives of fallen Greek heroes were celebrated with elaborate games, chariot races and processions, as in the funeral sponsored by Achilles for the death of his friend Patrokles. Geometric style vases, from the 8th century BC, are decorated with scenes from funeral procession. Schematic, stick-like figures raise their arms to show they are grieving for the deceased. The figural design is a composite type: frontal torso, profile face and a single, huge eye.

Even older than Greek and Egyptian representations are two small terra cotta statues from Cernavoda, Romania, c. 4,000 BC. Found in a burial close to the Danube River, these statues could be mourning figures. The man’s arms are raised while the woman’s arm is on her knee, her shape suggesting fertility and hope for continuity. I can’t help but think these little figurines were made by the ancestors of Mycenaean or Dorian Greeks who in a later era migrated down into Greece.

The male figure is sometimes called “The Thinker,” but these clay figures from Cernavoda, Romania may be mourners who accompany an important person in burial. The raised arms to show grief was later used by Greeks. They also remind me of Brancusi and Henry Moore.

The exhibition stays until April 15 in Richmond, the last destination in a 2-year, 7-city tour in the United States, including the New York Metropolitan Museum. Next they will go to the Cluny Museum on Paris before returning home. It will be interesting to see how they are displayed when they go home to Dijon.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 8, 2011 | Caryatids, Erechtheion, Greek Art, Mythology, Sculpture, the Acropolis

Six famous women hold up the Porch of the Maidens of the Erechtheion, a temple on the Acropolis of Athens. These statues are admired for their graceful poses and drapery, but who notices the hair? An Art Historian who specializes in the sculpture of the Acropolis, Katherine Schwab, has studied the hairstyles and made a project of it for her students at Fairfield University in Connecticut. Here’s a summary of a presentation she gave last night at the Greek Embassy in Washington.

In the New Acropolis Mus eum, Athens –which was just built a few years ago — one can see the statues from the back with their beautiful long braids of hair, falling in fishtails followed by more curls. In fact, the hair of the statues is in better condition than the faces and bodies whose arms are completely missing. (Caryatid is the name given to a feminine statue which acts as a column to hold up a building; Kore is a statue of a maiden.)

eum, Athens –which was just built a few years ago — one can see the statues from the back with their beautiful long braids of hair, falling in fishtails followed by more curls. In fact, the hair of the statues is in better condition than the faces and bodies whose arms are completely missing. (Caryatid is the name given to a feminine statue which acts as a column to hold up a building; Kore is a statue of a maiden.)

These six caryatids are

labeled Kore A – Kore F.

Every hairstyle is a bit different. Most have fishtail braids down the back, along with regular braids wrapped around the head. Some of the caryatids have sidecurls, while others do not. Professor Schwab did the Caryatid Project with hai r stylist Miloxy Torres who recreated the braids on 6 students, all of whom had long, thick and mainly curly hair. The students acted out the caryatid poses other at the Fairfield University c

r stylist Miloxy Torres who recreated the braids on 6 students, all of whom had long, thick and mainly curly hair. The students acted out the caryatid poses other at the Fairfield University c ampus in 2009.

ampus in 2009.

The Porch of the Maidens adorns the Erechtheion which honors Athena, Poseidon, and two legendary kings Erechtheus and Krekops. It is an unusual building in many ways: three porches of different sizes going out in different directions. It was of special civic and religious significance to the ancient Athenians, because it marked the site of the contest between the god of the sea, Poseidon (Neptune) and Athena, goddess of war and wisdom, for control of Athens. In that competition presided over by legendary King Kekrops, Poseidon’s Neptune struck a hole on a rock to bring forth a spring of salt water. Nearby, in front of the building, Athena miraculously brought to life an olive tree. Athena’s gift was deemed greater and she became the ruler of Athens. One portion of the Erechtheion contains a wooden statue of Athena which fell from heaven during the reign of Erechtheus, but the Porch of the Maidens stands over the hole where Poseidon tapped his trident.

|

| The original caryatids are now on view in the New Acropolis Museum, Athens |

The photos are from the Caryatid

Project and Wikipedia. For more information and a video, see

www.fairfield.edu/caryatid Here’s the video

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 25, 2011 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Architecture, Greek Art, Mythology, Sicily

In Selinunte, Sicily, the remains of several Greek temples from the 6th- 5th century

In Selinunte, Sicily, the remains of several Greek temples from the 6th- 5th century

BC can reveal much about temple construction, although they fell to Carthaginian invasions and earthquakes not long after their building. Architect Mark Schara,

with his good eye for detail, took almost all of these photos.

Temple E has most of its outer colonnade, the peristyle, restored.Classical harmony is apparent in the rhythm of fluted columns, continuing up into the triglyphs raised to the sky.

.

But many of the capitals have fallen. On the ground level, we can appreciate their large scale.

But many of the capitals have fallen. On the ground level, we can appreciate their large scale.

Temple F was badly damaged. Much of the white stucco facing for the fluted limestone column on right is still visible.

Temple G, below, was the largest of the 7 temples of Selinunte, the ancient city of Silenus.

This temple had columns about 54 feet tall. Here, we see the columns were made of individual segments called drums, each of which are 12 feet high

This temple had columns about 54 feet tall. Here, we see the columns were made of individual segments called drums, each of which are 12 feet high.

The overturned capitals, echinus on top of the abacus, has an 11′ diameter. Here, the abacus and echinus were carved in one piece, unlike above at Temple E.

At the time of destruction, not all of the capitals had been fluted. Thus we

know that the temple was never completed

Nearby in Agrigento, the ancient city called Akragas, had a series of ten temples in the Valley of the Temples.

The Temple of Concord is one of the best preserved Doric temples.

It had been converted into a church in the early Christian period.

In the 8th -3rd centuries BCE, Sicily was a battleground between Greeks who settled 3/4 of the island and Carthaginians who settled the western portion; then it became the target of Roman conquest.

Though only a small portion of the peristyle remains, the

Though only a small portion of the peristyle remains, the

Temple of Hera was in better condition than most of these temples

which fell victim to Carthaginian destruction, then earthquakes.

But an even taller temple to Olympian Zeus would have been the largest of Doric Greek temples, the height of a 10-story building; it was incomplete when the disaster struck.

Construction began in 480 BCE and was still in progress when it was decimated in 407 BCE. The Telemon or Atlas figures whose bent arms support the architravemay in fact represent Carthaginian prisoners who had been made to build the temple.

Construction began in 480 BCE and was still in progress when it was decimated in 407 BCE. The Telemon or Atlas figures whose bent arms support the architravemay in fact represent Carthaginian prisoners who had been made to build the temple.  But even these giants, who appear to have held up the building, have fallen,

But even these giants, who appear to have held up the building, have fallen,

struck down by the Carthaginians who conquered Akragras.

Only a replica of one of the ruined giants remains on the site.

Ancient Akragas may have had 200.000 people in the 5th century BCE.Today we witness the fallen giant as a symbol of human pride grown too large,

Ancient Akragas may have had 200.000 people in the 5th century BCE.Today we witness the fallen giant as a symbol of human pride grown too large,

and, consequently, fallen.Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 16, 2011 | Ancient Art, Greek Art, Sculpture, Sicily

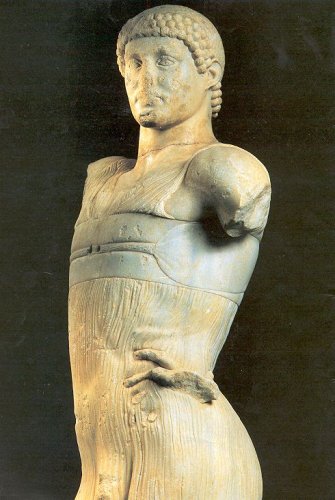

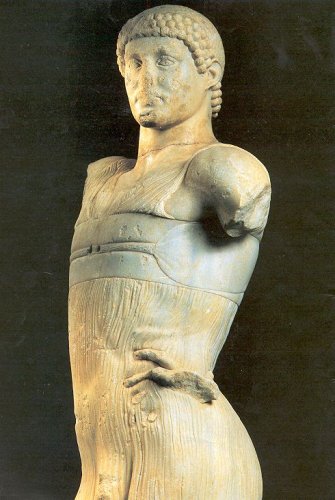

This tall elegant Charioteer of Mozia or “Giovane of Mozia,” was excavated in

1979. It brings up problems of identity, meaning and dating in Greek Art.

A life-size statue was dug up in 1979 in Mozia, ancient Motya, a tiny island adjacent to the west coast of Sicily. The slightly larger than life-size Youth of Mozia demonstrates why it is necessary for art historians to constantly re-evaluate conceptions of style, meaning and dating in art. Everyone agrees it belongs to the 5th century BCE, and, based on exact location of the find and the layer in which it was buried, it cannot be later 397 BCE. Yet Mozia was a Carthaginian settlement and the Carthaginians were constantly at war with Greeks who controlled most of Sicily. The questions are:

* Who is the subject?

* What is the date?

* Where was it made?

* Why did it end up in Mozia?

This statue has physical beauty, elegance, grace and transparent drapery. Feet and arms are missing but remnants of one hand dig into the corresponding hip, a marvelous detail which only an artist of great skill could execute. Much of the face is damaged, perhaps intentionally. The head was detached but has been put back. Although Most experts agree that the statue is Greek dating to the 5th century BCE, some have claimed the hair and face appear non-Greek and perhaps Carthaginian.

Bent arms in opposite directions would have created a vigorous counterpoise, a surprise

considering the rigidity of some conventional aspects of the head and hair.

The pose, vigorous turn and thin, transparent drapery would suggest a classical date of 450-420 BCE. “Wet drapery” is

mainly a convention of female figures of this High Classical period or end of the 5th century BCE, as in the Parthenon goddesses or on the Temple of Athena Nike. Yet there are contraindications to a late 5th century date. Hair is very stylized, and therefore, Archaic, and the facial modeling is most akin to the Severe Style, 480-450 BCE. To get better idea of a date, we can compare to other Greek sculptures, and I will fill in a suggested idea of identity.

When I compare this beautifully carved wet drapery to other works, the strongest analogy is found to the Ludovisi Throne, probably representing the birth of Aphrodite. This relief, dated c. 460 BCE, is now in Rome, but is known to have been connected to an Ionian temple of Aphrodite in Locri, a far southern city in Italy. (Both Sicily and southern section of Italy were heavily Greek in the centuries before the Roman conquest.)

The Ludovisi Throne, usually dated to 460 BCE, comes from a Greek colony is

south Italy. It has similar “wet drapery.”

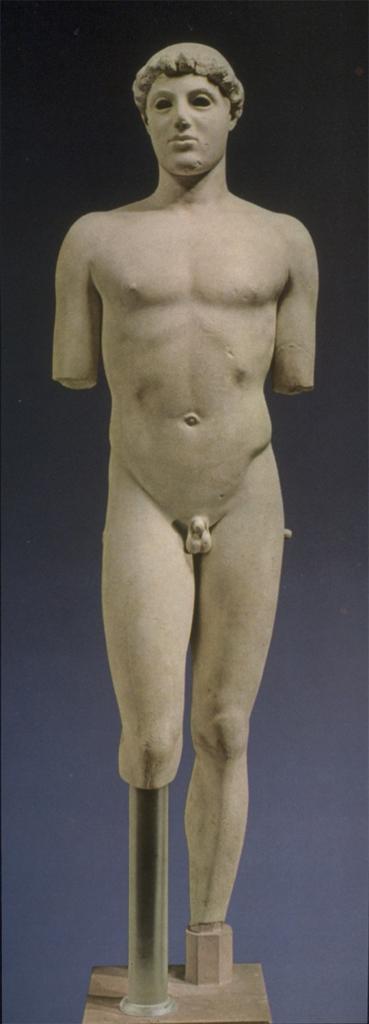

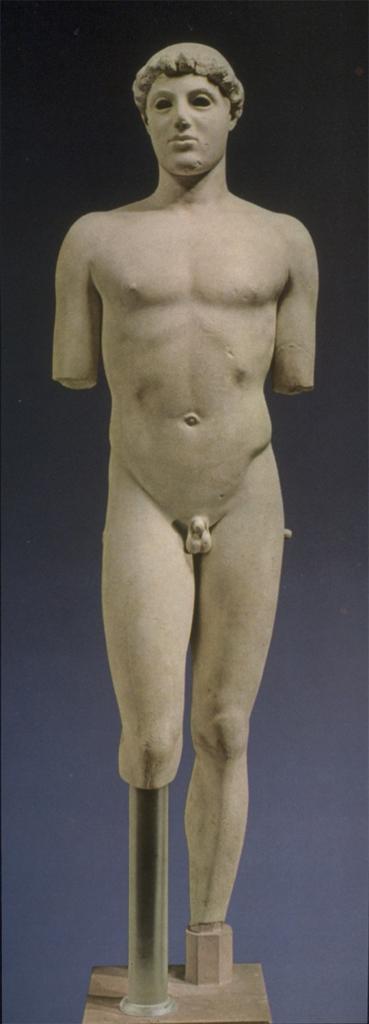

When I look at the profile, I’m reminded of the Kritios Boy, c. 480 BCE,

also in marble, although the Kritios Boy had inlaid eyes of another

material. Short stylized

hair held down on the scalp are characteristic of both statues. The Mozia youth’s capped hair ends in ringlets, an atypical feature, but not without parallels. It’s unfortunate the center of this figure’s nose, mouth and chin are no longer visible in their original form for a perfect comparison.

The profile of the Mozia marble reveals holes in the ear and even some bronze in the back of the head, perhaps an attachement for the victory wreath of a charioteer.

The Kritios Boy,below, is in better condition.

His eyes, missing, were inlaid with another, colored material.

The Charioteer of Delphi, c. 470 BCE, is bronze and has original inlaid eyes.

He is a victorious chariot driver from Sicily but was dedicated in Greece.

The bronze cast Charioteer of Delphi, c. 470 BCE, represented the winner of the Pythian games who came from the city of Gela in Sicily, but the statue was made in Greece and erected to Apollo in thanks for a victory Apollo at the god’s sanctuary in Delphi. He has copper inlays for lips and eyelashes, onyx for eyes and silver for the victory wreath, which fortunately remain intact. Yet the Delphi Charioteer, c. 470 BCE, is more rigid than our marble example and his face is mask-like. He was part of a bronze group composition, standing behind 4 horses and such stoic emotion was needed for the concentration of an athletic victor. (Remains of the horses, reins and the statue base with dedication are extant.)

The Mozia figure also wears a ankle-length chiton, the

xystis that all chariot drivers wore, although without sleeves and in a very light fabric. Besides the

xystis, there are other reasons that the Mozia youth can be considered a charioteer. His thick belt of a stiff material compares to the belted chests of charioteers seen on Sicilian coins dated to 460 BCE and later, an alternative to the Delphic Charioteer’s belt on the waist and back. Such belts or ties were necessary to keep the fabric from billowing in the wind and interfering during a race. Here we see large holes to which a bronze belt buckle must have been attached. Finally, holes in the head above the row ringlets held bronze nails, two of which remain, evidence of a victory wreath attached to the original statue. The right arm, missing, was probably raised to attach the wreath, while the left arm was bent nonchalantly where the remaining hand reaches below at the hip. T

he statue may be something the charioteer himself erected to honor his victory, and placed it at home in Sicily, rather than in a sanctuary dedication on the mainland of Greece. (These details are explained by Professor Bell, who suggests it was made by a Greek artist for a victorious Sicilian charioteer patron.)

The Kritios Boy, about 480 BCE right, is in the Severe Style.

He is slightly under 4 feet tall.

The statue from Mozia has a stonger

shift to his hips than the Kritios Boy.

The Kritios Boy was excavated with many other statues in the Acropolis of Athens in 1865. It is generally known to mark the transition from Archaic to Early Classical or the Severe Style, as its legs shift position and transfer weight into a counterpoise, the relaxed pose of contrapposto. Severe Style art from 480-450 BCE is known for its stoicism or a lack of facial emotion.

There is a youth from Sicily made around the same time as the Kritios Boy, the Ephebe of Agrigento. If we compare his face with the Mozia figure, we see the similarities, a serious demeanor with broad feat ures, less elongated than the Kritios Boy or the Charioteer at Delphi. So questions of his “Greekness” should be eliminated.

ures, less elongated than the Kritios Boy or the Charioteer at Delphi. So questions of his “Greekness” should be eliminated.

The Ephebe of Agrigento (ancient Akragas), left, comes

from Sicily and is dated around

the time of the Kritios Boy, above.

Why was the Mozia Charioteer, if made by a Greek for a Greek in the 5th century, found in Mozia? In a constant battle between Greeks and Carthaginians, with the major Greek cities being ravaged between 409 and 405 BCE, this prized statue would have been captured as war booty. If you have any thoughts of date or identity to add to this blog, please comment.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments