As with so many archeological sites, the excavation of a Greek settlement in east central Sicily, Morgantina, was subject to theft and sale of its treasures, notably a cache of fine silver and the Morgantina Acroliths, statues with only the marble heads hands and feet. The rest of the bodies may have been wood or cloth. These acroliths can be compared to the “Warka Mask,” a marble head dating back at least five millennia to ancient Uruk in Iraq, which was looted in 2003 but recouped by authorities at the Iraq Museum in Baghdad. The Morgantina acroliths have also returned close to home recently, on display since 2008 in Aidone, a town of about 6,000 inhabitants near Morgantina.

For the archeologist, art hist

orian, the regional and national governments, and the museum world, the Morgantina acroliths pose many questions:

- Why were statues made of marble only in the head, hands and feet?

- Who are the subjects or goddesses represented by the statues?

- How do we repatriate stolen goods? And do museums have the moral obligation to return items if they are later found to be looted?

- When back in their home location, how should the statues, with missing parts, be displayed?

These expressive faces charm us with their smiles . Marble–not as abundant in Sicily as in Greece–was limited to head, feet and hands. However, it is easy to see the Morgantina heads as comparable in style and date to the well-known Peplos Kore from Athens.c. 530 BCE. They could have been made later if made in a provincial location, such as Morgantina. (Morgantina is 126 km from Sircusa, the great city of Syracuse in Greek Sicily.) Unquestionably feminine, the Morgantina heads are very much alike, although one woman is clearly more mature than the other, giving us hints of their relationship.

Below, a Sicilian fashion designer has clothed the acroliths. Demeter has both her

hands and feet, while only one hand and foot belong to Persephone, also called Kore.

Demeter, goddess of grain, and her daughter, Kore, are the likely identities of the goddesses who sat in a sanctuary of ancient Morgantina. The particular honor given to these goddesses in Sicily was tied to mythology and to the island’s fertility, as the soil was less rocky and more fertile than in Greece. According to mythology, Hades of the underworld abducted Demeter’s daughter and caused deep pain. On a frantic search for Kore, the goddess of grain scorched the earth and let all vegetation die. Zeus promised the return of her daughter if she agreed to send her into the underworld for half of every year. For that reason, Kore, also called Persephone, goes underground every autumn. According to myth, Sicily, specifically Enna (Morgantina is in the province of Enna), was the site of Kore’s abduction. When Demeter brought her daughter back from the underworld and restored the grain, Sicily was the first place to which vegetation returned. Paying homage to Demeter and her daughter, goddess of the underworld, insured fertility of the land. The cult of Demeter and Kore was strong throughout ancient Sicily, with more sanctuaries dedicated to these goddesses than any other gods or goddesses.

The unfortunate stealing of Persephone into the underworld played itself out again in 1978, when professional tomb robbers dug up the acroliths and, through a network of dealers, sold them. A private collector, perhaps unaware that the marbles were obtained illegally, paid $1,000,000 for the goods. Through a laborious process of tracking down what happened to the acroliths, as well as other stolen items from Morgantina, Professor Emeritus Malcolm Bell of the University of Virginia pursued the goal of returning them to their region of origin. The collector gifted the marbles to the University of Virginia Art Museum with the knowledge they would eventually go back to Sicily. The problem of repatriating stolen goods has been a difficult one for American museums to address in recent years.

Demeter the mother, left, and her daughter, Persephone (also called Kore), right

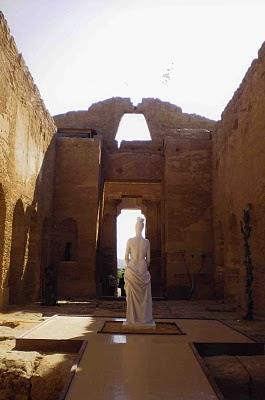

The goddesses now sit together in their own room, like a cult chamber, in the Aidone Archeological Museum. The artful display has special lighting and new armatures and clothing designed by a fashion designer from Sicily, Marella Ferrara. The goal is to make the display as authentic as possible, giving the public an impression as they may have appeared in ancient times. (I still wonder if Demeter was holding sheaths of wheat? Kore holding a pomegranate?) Gauze-like coverings are suggestive but not definitive of how the statues may have been in a cult sanctuary. We can once again witness the mysteries of Demeter and Persephone in a space about 2 km from their original home.

This is the first of 5 blogs on archeology in Sicily which will cover topics in art and architecture that can trace the island’s history from the Archaic Greek period through the late Roman period in Sicily. I must thank Mark Schara and Kelli Palmer who have shared their photos.

This is the first of 5 blogs on archeology in Sicily which will cover topics in art and architecture that can trace the island’s history from the Archaic Greek period through the late Roman period in Sicily. I must thank Mark Schara and Kelli Palmer who have shared their photos.

Recent Comments