by Julie Schauer | Feb 25, 2014 | Byzantine Art, Cathedral of Hildesheim, Christianity and the Church, Exhibition Reviews, Metalwork, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mosaics, National Gallery of Art Washington, The Middle Ages

Archangel Michael, First half 14th century tempera on wood, gold leaf

overall: 110 x 80 cm (43 5/16 x 31 1/2 in.) Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens

Gold radiates throughout dimly-lit rooms of the National Gallery of Art’s exhibition, Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Art from Greek Collections. Some 170 important works on loan from museums in Greece trace the development of Byzantine visual culture from the fourth to the 15th century. Organized by the Benaki Museum in Athens, it will be on view until March 2 and then at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles beginning April 19. The National Gallery has a done a great job organizing the show, getting across themes of both spiritual and secular life spanning more than 1000 years. The exhibition design is masterful and includes a film about four key Greek churches. The photography is exquisite and provides the full context for the Byzantine church art.

There are dining tables, coins, ivories, jewelry and other objects, but it’s the mosaics which I find most captivating, and this exhibition allows a close-up view. Their nuances of size and shape can be closely observed here, but not in slides or in the distance. Byzantine artists gradually replaced stone mosaics with glass tesserae, painting gold leaf behind the glass to portray backgrounds for the figures. It was the Byzantines created these wondrous images by transforming the Greco-Roman tradition of floor mosaics to that of wall mosaics.

|

| Van Eyck, St John the Baptist, det-Ghent Altarpiece |

|

|

New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art recently hosted another exhibition of the Middle Ages, “Treasures from Hildesheim,” works from the 10th through 13th centuries from Hildesheim Cathedral in Germany. Even though Greek Christians of Byzantine world officially split from Rome in the 11th century, the two exhibitions show that the art of east and west continued to share much in terms of iconography and style. Jan Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, from the 15th century, contains a Deesis composed of Mary, Jesus and John the Baptist, in its center, proving how persistent Byzantine iconography was in the West. That altarpiece shows the early Renaissance continuation of imagining heaven as glistening gold and jewels.

Church architecture evolved very differently however, with the Latin church preferring elongated churches with the floor plan of Roman basilicas. The ritual requirements of the Orthodox Church resulted in a more compact form using domes, squinches and half-domes. Fortunately, the National Gallery’s exhibition has a lot of information about Orthodox churches, their layout and how the Iconostasis (a screen for icons) divided the priests from the congregation.

|

| Reliquary of St. Oswald, c. 1100, is silver gilt |

Both cultures re-used works from antiquity. In the East, the statue heads of pagan goddesses could become Christian saints with a addition of a cross on their foreheads. In the west, ancient portrait busts inspired gorgeous metalwork used for the relics of saints, such as the reliquary of St. Oswald, which actually contained a portion of this 7th century English saint’s skull. Mastering anatomy, perspective and foreshortening was not as important an aim as it was to evoke the glory and golden beauty of heaven as it was imagined to be. The goldsmiths and metalsmiths were considered the best artists of all during this period in the west.

|

Mosaic with a font, mid-5th century Museum of

Byzantine culture, Thessaloniki

Photo source: NGA website |

|

|

|

Perhaps the parallels exist because many artists from the Greek world went to the west during the Iconoclast controversy, spanning most years from 726 to 843. Mosaic artists from the Byzantine Empire peddled their talents in the west, particularly in Carolingian courts of Charlemagne and his sons. From that time forward certain standards of Byzantine representation, such as the long, dark, bearded Jesus on the cross. While we seem to see these images as either icons or mosaics in Greek art, they become symbols in the west, often translated into sculptures of wood, stone or even stained glass.

An interesting parallel of the two exhibitions is the early Byzantine fountain, a wall mosaic of gold, glass and stone in the NGA’s exhibition, which compares well to the 13th century Baptismal font from Hildesheim, showing the Baptism of Christ. The font mosaic is from the Church of the Acheiropoietos in Thessaloniki. It is thought to emulate the fountains and gardens of Paradise. One can visualize of the context in which the fragmentary mosaic was made by watching the film in the exhibition, which shows another wondrous 5th century church in Thessaloniki, the Rotonda Church.

|

A Baptismal Font, 1226, is superb example of Medieval

metalwork from Hildesheim Cathedral. |

The exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum had a life-size

wooden statue of the dead Jesus, dated to the 11th century, originally on a wood cross, now gone. Wood carvers out of Germany were masters of emotional expression. In the iconic

Crucifixion image in the Greek exhibition, a very sad Mary and Apostle John are grieving at the side of Jesus. It’s poignant and emotional, with knit eyebrows, tilted heads and a profoundly felt grief.

|

| Golden Madonna is wood covered in gold, made for St. Michael’s Cathedral before 1002 |

|

The iconographic image of the Theotokos, a Greek type is normally a rigid, enthroned Mary who solidly holds her son, a little emperor. The format expresses that she is the throne, a seat for God in the form of Baby Jesus. From Hildesheim, there is a carved statue which dates to c. 970, carved of wood and covered with a sheet of real good. Both heads are now missing. At one time the statue was covered with jewels, offerings people had given to the statue. In the west, this type became common, called the sedes sapientaie, but the origin is probably Byzantium.

Although heaven is more important than earth, and God and saints in heaven are more powerful than humans, sometimes medieval artists have been capable of revealing the greatest truths about what it’s like to be a human being. In the icons, there is great poignancy and beauty in the eyes. At times the portrayal of grief is overwhelming, as we see on an icon of the Hodegetria image where Mary points the way, the baby Jesus but knows He will die. On the reverse is an excruciatingly painful Man of Sorrows.

|

| Icon of the Virgin Hodegetria, last quarter 12th century, tempera and silver on wood, Kastoria, Byzantine Museum. On the Reverse is a Man of Sorrows |

The Metropolitan exhibition of course could not bring the two most important works from Hildesheim, the bronze relief sculptures: a triumphal column with the Passion of Christ and a set of bronze doors for the Cathedral. Completed before 1016, I often think of the figures on the relief panels on those doors as one of the most honest works of art ever created. As God convicts Adam of eating the forbidden fruit, Adam crosses his arm to point to Eve who twists her arms pointing downward to a snake on the ground. We may laugh because God’s arm seems to be caught in his sleeve as he points to Adam. Though this medieval artist/metalsmith (Bishop Bernward?) may not have understood anatomy and perspective, he understood how easy it is for humans to pass the blame and not take responsibility for their actions.

|

| The Expulsion, before 1016, detail of bronze door, St. Michael’s, Hildesheim |

Medieval artists in both the Greek and Latin churches are normally not known by name. After all, their work was for God, not for themselves, for money or for fame.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Jan 26, 2014 | Asian Art, Buddhism, Collage, Folk Art Traditions, Mandalas, Medieval Art, Mosaics, The Sackler Gallery of Art

|

Temporary floor mandala, flashed by light onto the floor

of the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery of Asian Art |

Mandalas, an important tradition in India, Nepal and Tibet have spread well into the West, or as some think, have always been in the West. The exhibition, Yoga: The Art of Transformation at the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery of Art, takes us into art and history surrounding the physical, spiritual and spiritual exercise of yoga. It’s the first exhibition of its kind. This is the last weekend of the show, featuring works of art in Hindu, Jain and Buddhist practice. Yoga hold some keys to mental and physical healing.

We’re led into yoga’s 3,000-year history by a series of light patterns flashed on the floor–patterns that are mandalas and have lotus patterns. (Lotus is also the name of a yoga pose.) After this weekend, they’ll be gone with the show, but that’s the spirit of mandalas, at least in the Tibetan tradition.

|

| Light Pattern on the floor of the Sackler Gallery of Asian Art forms a Mandala |

Mandalas have radial balance, because their designs flow radially from the center, somewhat like the spokes of a wheel. Traditional Buddhist monks in Tibet spend time together making mandalas of colored sand, working from the center outward using funnels of sand that form thin lines. Deities are invoked during this process of creation, following the same ancient pattern of 2,500 years. The creation is thought to have healing influence. Shortly after its completion, a sand mandala is poured into a river to spread its healing influence to the world.

|

| Chenrezig Sand Mandala was made for Great Britain’s House of Commons in honor of the Dalai Lama’s visit in May, 2008. Material: sand, Size: 7′ x 7′ Source of photo: Wikipedia |

|

|

|

Like the Buddhist Stupas which began in India, the Mandalas are microcosms of the macrocosm, or small replicas of the universe. Yantras are mandalas that are an Indian tradition which may have a more personal meaning. Their beautiful geometric designs can be highly efficient tools for contemplation, concentration and meditations. Concentrating on a focal point, outward chatter ceases and the mind empties to gain a window into truth. Making mandalas can be a powerful aid in Art Therapy.

|

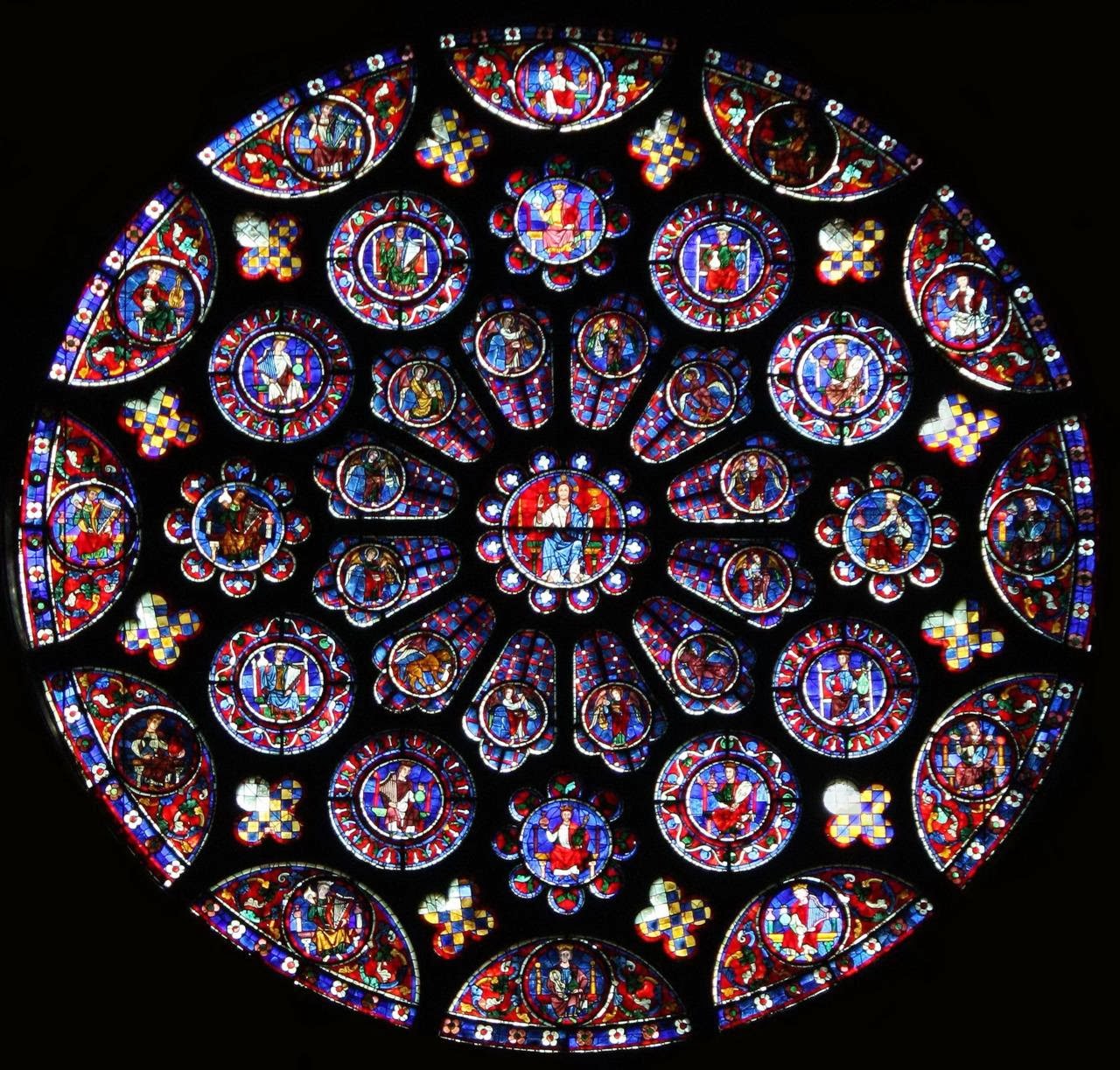

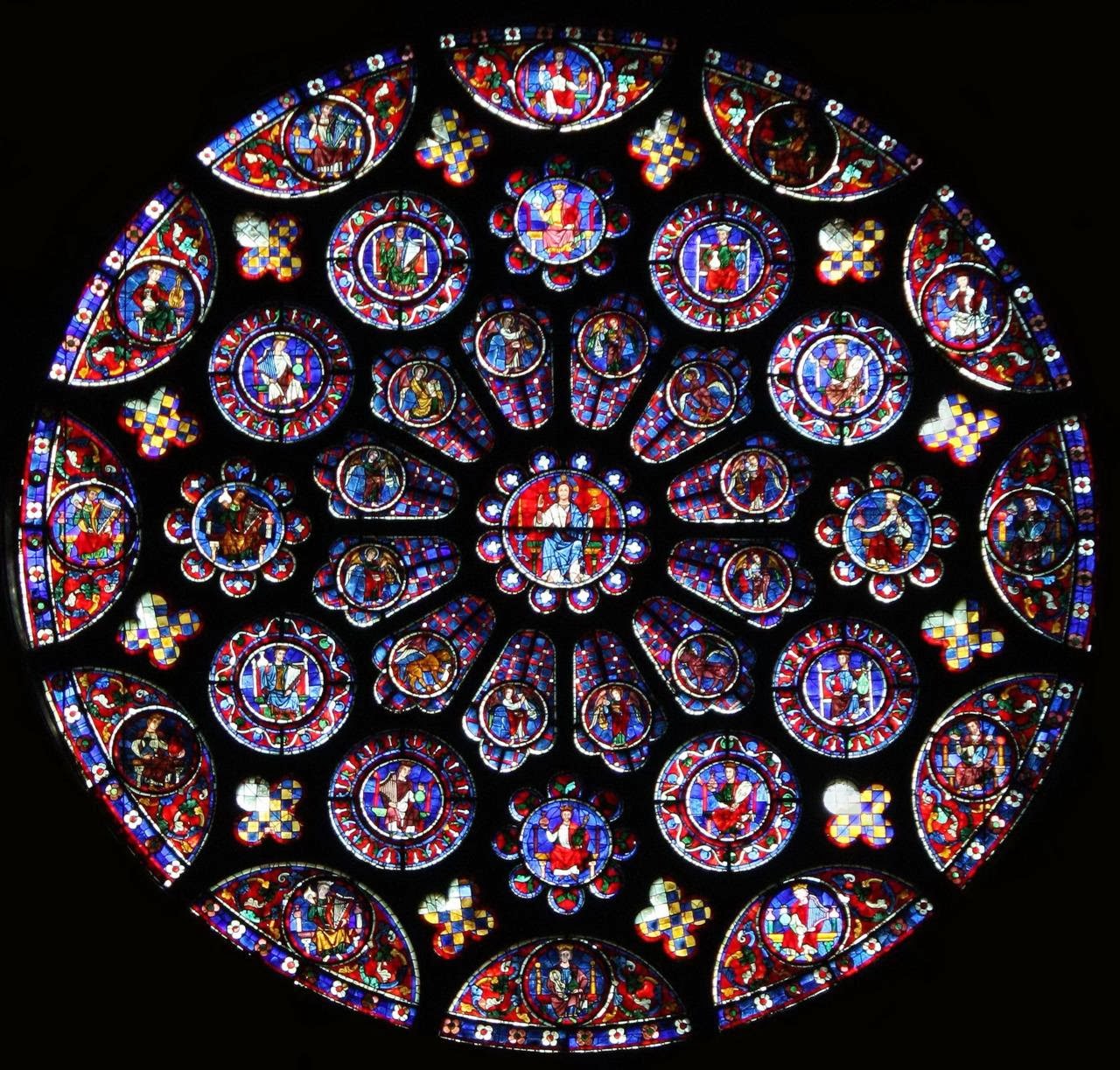

| North Rose Window of Chartres Cathedral, France, c. 1235 |

Circles, without a beginning or end, have an association with God and perfection. They’re an integral part of the design of Gothic Cathedrals, such as Chartres Cathedral and Notre-Dame of Paris which are among the most famous. Their patterns radiate out from the center, into rose patterns. I didn’t believe it when, years ago, a student mentioned they were inspired by Indian mandalas. The greater possibility is that spiritual wisdom comes from the same or similar sources.

|

Sri Chakra Mandala, ceramic tile, made by Ruth Frances Greenberg

17-1/4″ x 17-1/4″ x 1-1/4′ photo Lubosh Cech |

Artist Ruth Frances Greenberg makes ceramic tile mosaic mandalas in her Portland, Oregon studio, and sells them for personal and decorative use. Some are inspired by the Om symbol and by the home blessing doorway mandalas of Tibet. Others are inspired by the Chakras, the energy centers in ancient Indian tradition. The Sri Chakra Mandala has nine interlocking triangles and beautiful geometric complexity. It combines the basic geometric shapes of circle, square and triangle, and expresses powerful energies.

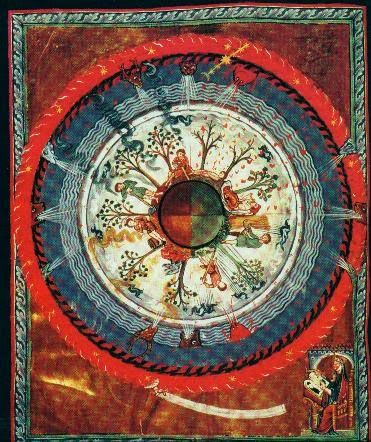

The circle within a square is common in many traditions, but in Indian art the openings of the square represent gateways. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, a study of perfection in human proportions, has a circle within a square. Medieval mystic, St. Hildegard of Bingen, a Doctor of Church, wrote music and created art in response to her visions. Wheel of Life is one of her many visions that were put into illumination in the mandala form, in the 12th century.

Chicago artist Allison Svoboda makes mandalas from a surprising combination of media: ink and collage. She explains, “The same way a plant grows following the path of least resistance, the quick gestures and simplicity of working with ink allows the law of least resistance to prevail….With this process, I work intuitively through thousands of brushstrokes creating hundreds of small paintings. I then collate the work…When I find compositions that intrigue me, I delve into the longer process of collage. Each viewer has his own experience as a new image emerges from the completed arrangement. The ephemeral quality of the paper and meditative aspect of the brushwork evoke a Buddhist mandala.”

|

| Allison Svoboda, Mandala, GRAM, 211–detail |

The 14′ by 14′ Mandala GRAM from the Grand Rapids Art Museum is a radial construction with many inner designs. Some of these designs resemble a Rorschach test, but infinitely more complicated.

The intricacies of the GRAM Mandala alternate and change as our eyes move around it. It’s like a kaleidoscope or spinning wheel. But a configuration in center pull us back in, reminding us to stay centered and whole, as the world changes around us.

|

| Allison Svoboda, Mandala, GRAM, 2011, Grand Rapids Museum of Art, in on paper, collaged 14′ x 14′ |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Jan 18, 2014 | Marc Chagall, Mosaics, Mythology, National Gallery of Art Washington

|

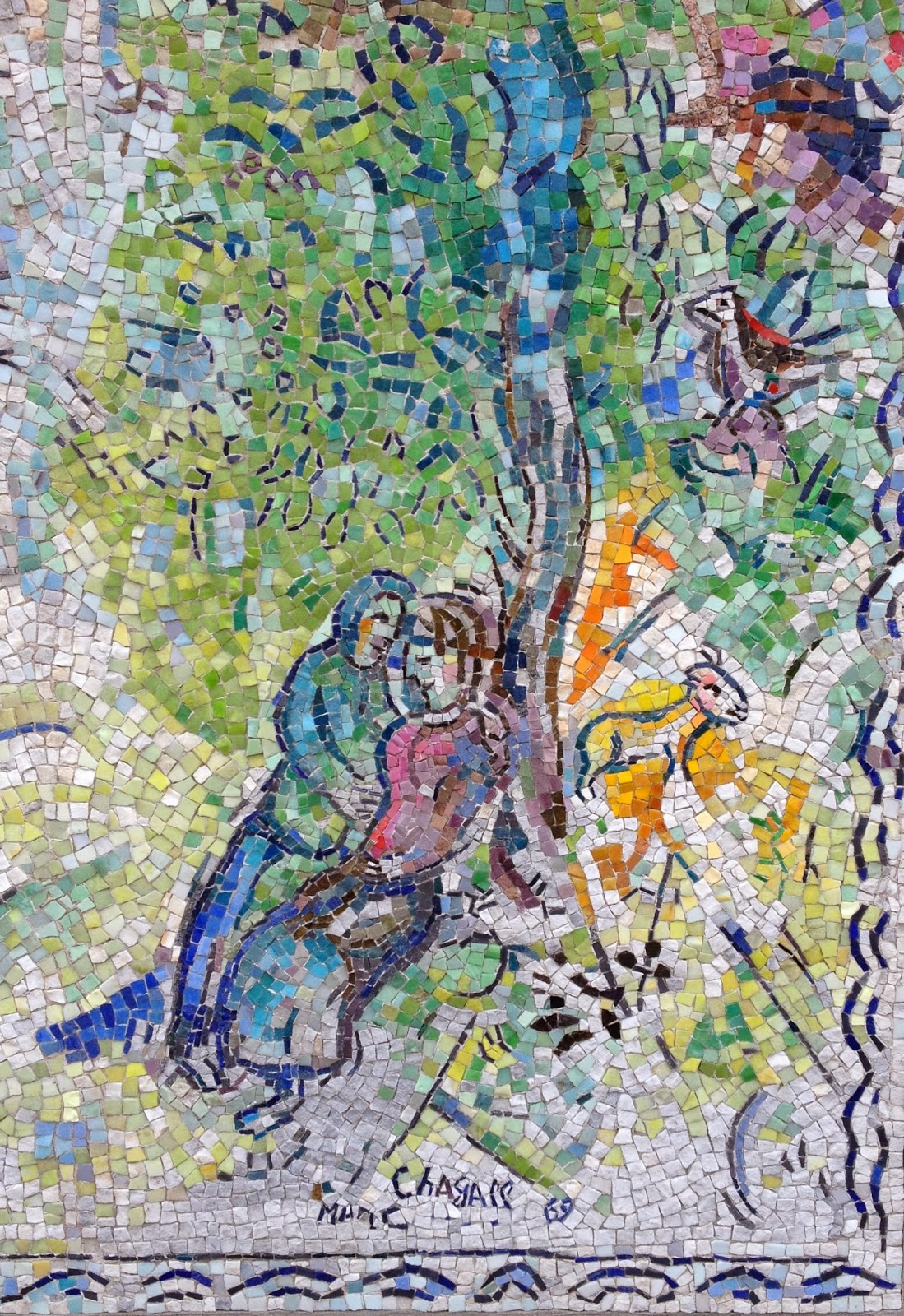

Detail – Marc Chagall, with Lino Melano, Orpheus, 1971, from the upper

right side–Pegasus, Three Graces, Orpheus

|

The nation’s capital city added a sudden burst of color this season in the form of Marc Chagall’s Orpheus, a glass and stone mosaic. It’s a 17′ by 10′ wall standing in the National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden, between 7th and 9th Streets, NW, Constitution Avenue and Madison Avenue. Evelyn Stephansson Nef, who died in 2009, donated it to the museum. (The composition is one of three new acquisitions in the National Gallery, a must-see along with a Van Gogh, a Gerrit von Honthorst and a loan of the Dying Gaul from the Capitoline Museum in Rome.)

The mosaic stands in the garden behind the restaurant, but in front of the heavily traveled Route 1. Fortunately, a lot trees shield it from view of the traffic, providing a reflective space for viewers. The sculpture garden is on the National Mall, but open only from 10-5 daily and 11-6 Sundays, except for an ice rink in winter which has longer hours.

Evelyn Nef and her husband, John Nef, were friends of the artist who was inspired after visiting them in 1968. The artist gave the mosaic to the couple back in 1971. For years, it was in the garden of their Georgetown residence, vaguely visible from the street. The National Gallery spent years preparing, repairing, moving and re-installing its 10 separate concrete panels, a process described in the Washington Post. The seams aren’t visible.

|

Detail, Marc Chagall, Orpheus, 1971. Here Orpheus

is crowned and holds his lyre. |

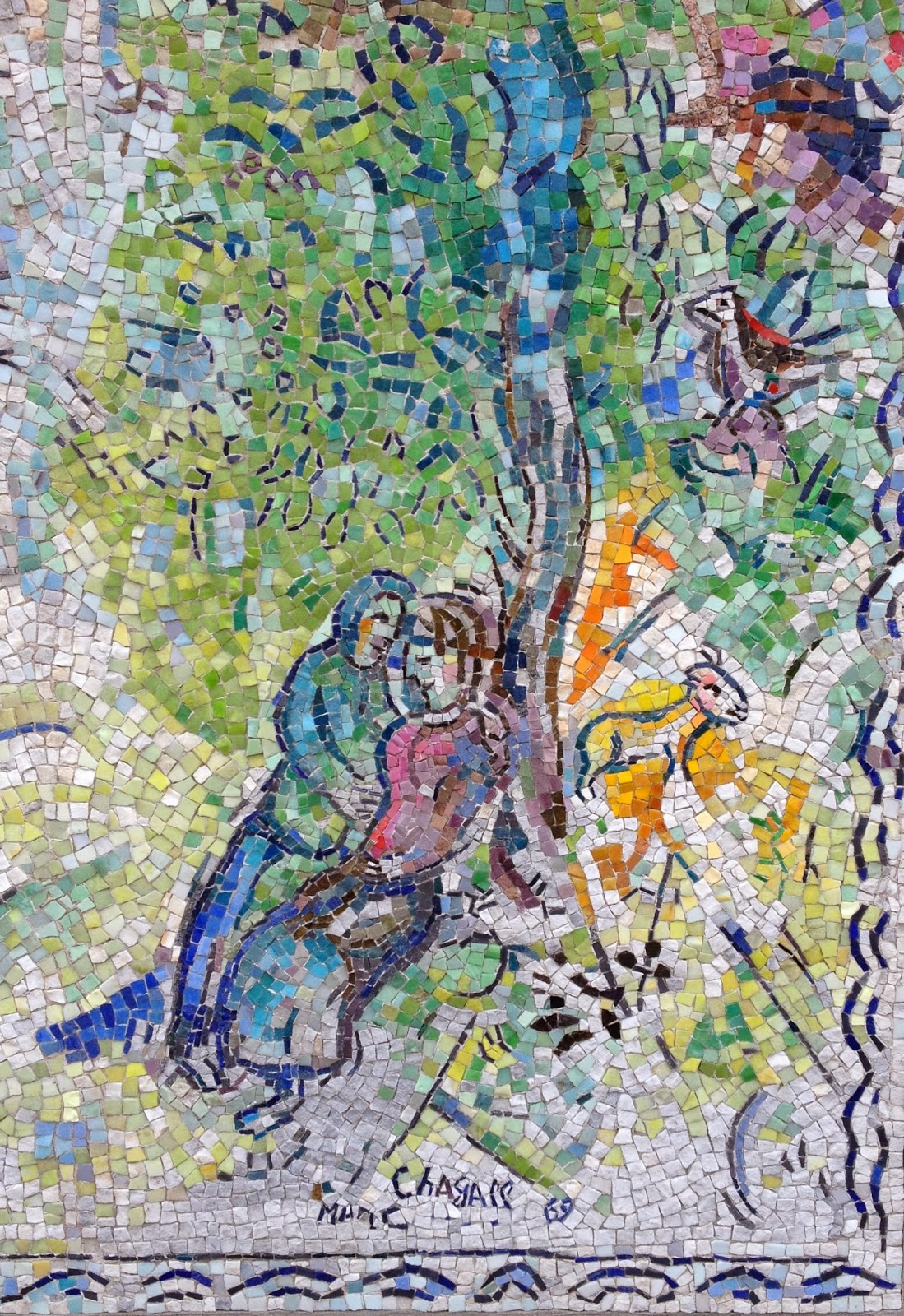

Chagall did the drawings for the composition in his studio back in France, and then hired mosaicist Lino Melano to complete it. Melano supervised installation which was finished in November, 1971. The artist returned at the time to see it. It was his first mosaic installed in the US. Afterwards, Chagall did the renowned Four Seasons mosaics for the First National Plaza in Chicago.

The composition has the spontaneity, verve and joy we can expect from Chagall. The execution, however, took a highly skilled Italian mosaicist who was steeped in the tradition. Melano used Murano glass, natural-colored stones and stones cut from Carrara marble. On close inspection, viewers can discern where there is glass: in the most brightly-colored passages, the shining blues, reds and radiant yellows. There is a touch gold leaf behind some of the glass, a technique inherited from the Byzantine mosaicists.

(For a good comparison, Byzantine mosaics are currently on view in the marvelous National Gallery Exhibition, Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Art from Greek Collections, until March 2, 2014.) Byzantine mosaics also combine stone cubes and glass cubes, called tesserae, but the tesserae are much, much smaller in Byzantine mosaics.

Melano wisely reserved the gold leaf for a few choice places, but only on Orpheus, his crown and his knee.

|

Detail, Marc Chagall, Orpheus, mosaic, 1971. Figures cross the ocean,

with an angel guide, the sun and mythological horse, Pegasus |

The god Orpheus is shown without his ill-fated mortal lover, Eurydice. Eurydice lost him because she disobeyed fate and dared to turn back and look at him while in the underworld. Chagall ignores the pessimistic part of the story. How then do we interpret what Chagall was trying to convey?

The other mythological figures are the flying horse Pegasus and the Three Graces. The winged-horse does not have feet, reminding me of the incomplete depictions of animals painted in the caves of southern France, near Chagall’s studio. Orpheus holds his lyre in a prominent position. Pegasus flies and Orpheus makes music while a little birdie flies. The Graces are not dancing here, but they remind us of our gifts and that grace is indeed possible. Chagall, who escaped Europe in the Holocaust, had a knack for putting a positive spin on events. He obviously chooses the highest potentials of human nature, while not exactly ignoring the negative.

|

| Detail, lower left corner with Chagall’s signature |

Of course the myth of Orpheus also conjures up images of the underworld. On the left, there is water where people are entering in groups and fishes are swimming. Could this be the River Styx of Greek mythology? Chagall said it referred to the groups of immigrants who crossed the ocean to get a better life. Above the river is a huge burst of sun. An angel flies triumphantly overhead, with open arms. The artist ignored the rules of perspective and foreshortening on this figure, reminding us that flight, or overcoming limitation, is indeed possible. He suggests that dreams can come true.

A dreaming couple on the bottom right hand side are happily in a paradise, under a tree. The artist’s signature is underneath. Chagall may have thought of himself with his wife, Bella. According to the National Gallery’s website, Evelyn Nef asked Chagall if this was her and her husband, John. He replied, “If you like.” There’s a border to the composition. Everywhere lines are curved, making this composition the image of life as a joyful journey, a graceful dance with much optimism.

|

Marc Chagall, Russian, 1887-1985, Orpheus, designed 1969, executed 1971, stone and glass mosaic

overall size: 302.9 x 517.84 cm (119 1/4 x 203 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

The John U. and Evelyn S. Nef Collection

2011.60.104.1-10 |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Nov 28, 2012 | Architecture, Christianity and the Church, Mosaics, Sculpture, Sicily, The Middle Ages

|

Sicily was controlled or settled at various times by Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Saracens,

Normans and Spaniards. This view is Monreale, in the north, east of Palermo. |

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

|

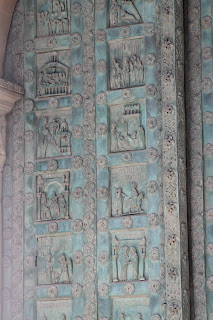

Bonnano of Pisa cast the bronze doors

in 1185 |

A Norman ruler, William II (1154-89), built Monreale Cathedral between 1174 and 1185. When the Roman Empire first became Christian, Sicily reflected the ethnic Greeks who lived on the island. In the 8th century, Saracens conquered Sicily and held it for two centuries, although a majority of residents were Christians of the Byzantine tradition. William the Conqueror’s brother Roger took over the island in 1085, but allowed the other groups to live peacefully and practice their religion. Normans, Lombards and other “Franks” also settled on the island, but the Norman rule between the late 11th and late 13th centuries was quite tolerant. By the 13th century, most residents adopted the Roman Catholic faith. Germans, Angevins and finally, the Spanish took control of the island.

|

This pair of figural capitals in the cloister could be a biblical

story such as Daniel in the Lion’s Den or even a pagan tale |

Monreale Cathedral was built on a basilican plan in the Romanesque style that dominated Western Europe in the 12th century, although the Gothic style had already taken hold in Paris at the time of this building. It is based on the longitudinal cross plan with a rounded east end. Two towers flank the facade. (This Cathedral ranks right up with Chartres and Notre-Dame of Paris, as one of the world’s most beautiful churches.)

|

Capitals feature men, beasts and beautiful

acanthus leaf designs |

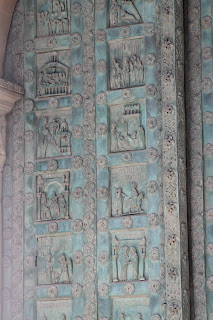

In the artistic and decorative details, there is great richness. The portal has one of the few remaining sets of bronze doors from the Romanesque period. These doors were designed and cast by a Tuscan artist, Bonanno da Pisa. A cloister, similar to the cloisters of all abbey churches has a beautiful courtyard with figural capitals. Its pointed arches betray Islamic influence. The sculptors who carved the capitals are thought to have come from Provence in southern France, perhaps because of similarity in style to abbey churches near Arles and Nîmes, places with a strong Roman heritage. However, on the exterior apse of the church is a surprise. It has the rich geometry of Islamic tile patterns. Islamic artists who lived in the vicinity of Monreale were probably called upon to do this work.

|

| Islamic artisans decorated the eastern side of the church with rich geometric patterns |

The Greek artists who decorated the Cathedral’s interior were amongst the finest mosaic artists available. The Norman ruler may have brought these great artisans from Greece. Monreale Cathedral holds the second largest extant collection of church mosaics in the world. The golden mosaics completely cover the walls of the nave, aisles, transept and apse – amounting to 68,220 square feet in total. Only the mosaics at Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey, cover more area, although this cycle is better preserved. The narrative images gleam with heavenly golden backgrounds, telling the stories of Biblical history. The architecture is mainly western Medieval while imagery is Byzantine Greek.

|

| Mosaics in the nave and clerestory of Monreale Cathedral |

A huge Christ Pantocrator image that covers the apse is perhaps the most beautiful of all such images, appearing more calm and gentle than Christ Pantocrator (meaning “almighty” or “ruler of all”) on the dome of churches built in Greece during the Middle Ages. The artists adopted an image used in the dome of Byzantine churches into the semicircular apse behind the altar of this western style church. Meant to be Jesus in heaven, as described in the opening words of John’s gospel, the huge but gentle figure casts a gentle gaze and protective blessing gesture over the congregation. He is compassionate as well as omnipotent.

|

Christ Pantocrator, an image in the dome of Greek churches, spans the apse

of this western Romanesque church. |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Mar 6, 2011 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Mosaics, Roman Art, Sicily

In the huge Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Armerina, Sicily, a girl is can be seen through the corridor………………..not one, but the room has 10 of these bikini girls engaged in some athletic activities. They are made of pieces of finely cut stone, set into mortar for a smooth finish on the floor. Mark Schara took these photos of the largest series of floor mosaics in the Roman Empire.

In the huge Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Armerina, Sicily, a girl is can be seen through the corridor………………..not one, but the room has 10 of these bikini girls engaged in some athletic activities. They are made of pieces of finely cut stone, set into mortar for a smooth finish on the floor. Mark Schara took these photos of the largest series of floor mosaics in the Roman Empire.  Their games include the discus throw, weight lifting and ball tossing. One with a palm and crown may be a winner.

Their games include the discus throw, weight lifting and ball tossing. One with a palm and crown may be a winner.

From the mosaics in ancient Sicily we can trace the art of stone floor mosaics, backwards. Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Amerina, covered by a landslide in the 13th century but now uncovered, has the largest group of extant mosaics from the Roman world. The cut marble stones decorated floors, not walls, of the palace. It is not known who built or owned the huge villa in the early 4th century, but it may be connected to the emperors, or gladiators in the late Roman Empire. There are several mosaics of giant figures and animals, representing diverse subjects like the Labors of Hercules, hunting and children fishing. One of the most surprising subjects is a group of young women, bikini girls. The floors of the entire villa are covered with remarkable picture puzzles.

Also at Villa Romana del Casale is the Room of Fishing Cupids. The children appear quite young and have curious markings on their faces .

At nearby Morgantina, three excavated homes have floor mosaics from the 3rd century BCE, some 500 years earlier than the Villa in Piazza Armerina. Above is a mosaic in the House of Ganymede, perhaps the earliest mosaic cut into cubes. Ganymede is being abducted by Zeus’ eagle, and the Greek key pattern in the border creates an optical illusion of shifting perspective patterns.

At nearby Morgantina, three excavated homes have floor mosaics from the 3rd century BCE, some 500 years earlier than the Villa in Piazza Armerina. Above is a mosaic in the House of Ganymede, perhaps the earliest mosaic cut into cubes. Ganymede is being abducted by Zeus’ eagle, and the Greek key pattern in the border creates an optical illusion of shifting perspective patterns.

Although we normally associate mosaics with the Byzantine wall mosaics in churches, the Hellenistic Greeks and Romans used them extensively. From Hellenistic times, three homes with mosaics have been excavated in Morgantina. Of special note is a mosaic in the House of Ganymede, made of marble and very finely executed, suggesting the wealth of central Sicily before the Roman takeover in 211 BCE. The House of Ganymede may, in fact, have the earliest mosaics found to be cut into squarish tesserae, the standard “tesselated” form for Roman and Byzantine mosaics. The best guess for a date is 250 BCE. It may copy a painting.

An animal mosaic from the Punic island of Mozia is the earliest known floor mosaic, perhaps from the early 4th century BCE. Composed of only gray, black and white pebbles, it was made before the famous pebble mosaics of Pella, Greece, from about 300 BCE.

An animal mosaic from the Punic island of Mozia is the earliest known floor mosaic, perhaps from the early 4th century BCE. Composed of only gray, black and white pebbles, it was made before the famous pebble mosaics of Pella, Greece, from about 300 BCE.

The oldest known floor mosaic is in Mozia, the small Punic island adjacent to Marsala, Sicily, which was conquered by Greeks in 397 BCE. In the House of the Mosaic, there is a floor carpet of real and imagined animals composed of black, white and gray pebbles. It lacks color and looks rough compared to later mosaics of both pebble and cut stone. Its border patterns — the Greek key, palmettes and waves — definitely look Greek. Does it come from shortly after the Greek conquest of 397 BCE? or even earlier?

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments