by Julie Schauer | Feb 16, 2011 | Ancient Art, Greek Art, Sculpture, Sicily

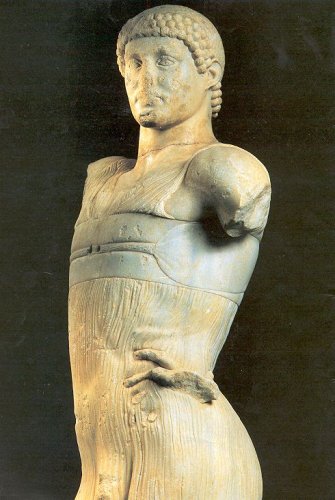

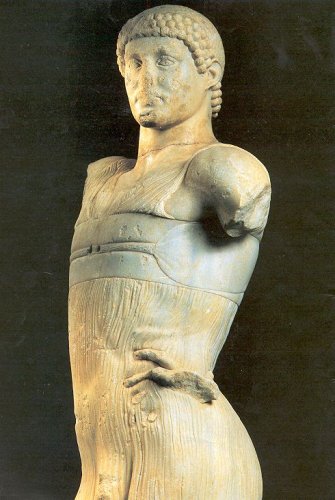

This tall elegant Charioteer of Mozia or “Giovane of Mozia,” was excavated in

1979. It brings up problems of identity, meaning and dating in Greek Art.

A life-size statue was dug up in 1979 in Mozia, ancient Motya, a tiny island adjacent to the west coast of Sicily. The slightly larger than life-size Youth of Mozia demonstrates why it is necessary for art historians to constantly re-evaluate conceptions of style, meaning and dating in art. Everyone agrees it belongs to the 5th century BCE, and, based on exact location of the find and the layer in which it was buried, it cannot be later 397 BCE. Yet Mozia was a Carthaginian settlement and the Carthaginians were constantly at war with Greeks who controlled most of Sicily. The questions are:

* Who is the subject?

* What is the date?

* Where was it made?

* Why did it end up in Mozia?

This statue has physical beauty, elegance, grace and transparent drapery. Feet and arms are missing but remnants of one hand dig into the corresponding hip, a marvelous detail which only an artist of great skill could execute. Much of the face is damaged, perhaps intentionally. The head was detached but has been put back. Although Most experts agree that the statue is Greek dating to the 5th century BCE, some have claimed the hair and face appear non-Greek and perhaps Carthaginian.

Bent arms in opposite directions would have created a vigorous counterpoise, a surprise

considering the rigidity of some conventional aspects of the head and hair.

The pose, vigorous turn and thin, transparent drapery would suggest a classical date of 450-420 BCE. “Wet drapery” is

mainly a convention of female figures of this High Classical period or end of the 5th century BCE, as in the Parthenon goddesses or on the Temple of Athena Nike. Yet there are contraindications to a late 5th century date. Hair is very stylized, and therefore, Archaic, and the facial modeling is most akin to the Severe Style, 480-450 BCE. To get better idea of a date, we can compare to other Greek sculptures, and I will fill in a suggested idea of identity.

When I compare this beautifully carved wet drapery to other works, the strongest analogy is found to the Ludovisi Throne, probably representing the birth of Aphrodite. This relief, dated c. 460 BCE, is now in Rome, but is known to have been connected to an Ionian temple of Aphrodite in Locri, a far southern city in Italy. (Both Sicily and southern section of Italy were heavily Greek in the centuries before the Roman conquest.)

The Ludovisi Throne, usually dated to 460 BCE, comes from a Greek colony is

south Italy. It has similar “wet drapery.”

When I look at the profile, I’m reminded of the Kritios Boy, c. 480 BCE,

also in marble, although the Kritios Boy had inlaid eyes of another

material. Short stylized

hair held down on the scalp are characteristic of both statues. The Mozia youth’s capped hair ends in ringlets, an atypical feature, but not without parallels. It’s unfortunate the center of this figure’s nose, mouth and chin are no longer visible in their original form for a perfect comparison.

The profile of the Mozia marble reveals holes in the ear and even some bronze in the back of the head, perhaps an attachement for the victory wreath of a charioteer.

The Kritios Boy,below, is in better condition.

His eyes, missing, were inlaid with another, colored material.

The Charioteer of Delphi, c. 470 BCE, is bronze and has original inlaid eyes.

He is a victorious chariot driver from Sicily but was dedicated in Greece.

The bronze cast Charioteer of Delphi, c. 470 BCE, represented the winner of the Pythian games who came from the city of Gela in Sicily, but the statue was made in Greece and erected to Apollo in thanks for a victory Apollo at the god’s sanctuary in Delphi. He has copper inlays for lips and eyelashes, onyx for eyes and silver for the victory wreath, which fortunately remain intact. Yet the Delphi Charioteer, c. 470 BCE, is more rigid than our marble example and his face is mask-like. He was part of a bronze group composition, standing behind 4 horses and such stoic emotion was needed for the concentration of an athletic victor. (Remains of the horses, reins and the statue base with dedication are extant.)

The Mozia figure also wears a ankle-length chiton, the

xystis that all chariot drivers wore, although without sleeves and in a very light fabric. Besides the

xystis, there are other reasons that the Mozia youth can be considered a charioteer. His thick belt of a stiff material compares to the belted chests of charioteers seen on Sicilian coins dated to 460 BCE and later, an alternative to the Delphic Charioteer’s belt on the waist and back. Such belts or ties were necessary to keep the fabric from billowing in the wind and interfering during a race. Here we see large holes to which a bronze belt buckle must have been attached. Finally, holes in the head above the row ringlets held bronze nails, two of which remain, evidence of a victory wreath attached to the original statue. The right arm, missing, was probably raised to attach the wreath, while the left arm was bent nonchalantly where the remaining hand reaches below at the hip. T

he statue may be something the charioteer himself erected to honor his victory, and placed it at home in Sicily, rather than in a sanctuary dedication on the mainland of Greece. (These details are explained by Professor Bell, who suggests it was made by a Greek artist for a victorious Sicilian charioteer patron.)

The Kritios Boy, about 480 BCE right, is in the Severe Style.

He is slightly under 4 feet tall.

The statue from Mozia has a stonger

shift to his hips than the Kritios Boy.

The Kritios Boy was excavated with many other statues in the Acropolis of Athens in 1865. It is generally known to mark the transition from Archaic to Early Classical or the Severe Style, as its legs shift position and transfer weight into a counterpoise, the relaxed pose of contrapposto. Severe Style art from 480-450 BCE is known for its stoicism or a lack of facial emotion.

There is a youth from Sicily made around the same time as the Kritios Boy, the Ephebe of Agrigento. If we compare his face with the Mozia figure, we see the similarities, a serious demeanor with broad feat ures, less elongated than the Kritios Boy or the Charioteer at Delphi. So questions of his “Greekness” should be eliminated.

ures, less elongated than the Kritios Boy or the Charioteer at Delphi. So questions of his “Greekness” should be eliminated.

The Ephebe of Agrigento (ancient Akragas), left, comes

from Sicily and is dated around

the time of the Kritios Boy, above.

Why was the Mozia Charioteer, if made by a Greek for a Greek in the 5th century, found in Mozia? In a constant battle between Greeks and Carthaginians, with the major Greek cities being ravaged between 409 and 405 BCE, this prized statue would have been captured as war booty. If you have any thoughts of date or identity to add to this blog, please comment.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 16, 2011 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Greek Art, Mythology, Sculpture, Sicily

This is the first of 5 blogs on archeology in Sicily which will cover topics in art and architecture that can trace the island’s history from the Archaic Greek period through the late Roman period in Sicily. I must thank Mark Schara and Kelli Palmer who have shared their photos.

This is the first of 5 blogs on archeology in Sicily which will cover topics in art and architecture that can trace the island’s history from the Archaic Greek period through the late Roman period in Sicily. I must thank Mark Schara and Kelli Palmer who have shared their photos.

As with so many archeological sites, the excavation of a Greek settlement in east central Sicily, Morgantina, was subject to theft and sale of its treasures, notably a cache of fine silver and the Morgantina Acroliths, statues with only the marble heads hands and feet. The rest of the bodies may have been wood or cloth. These acroliths can be compared to the “Warka Mask,” a marble head dating back at least five millennia to ancient Uruk in Iraq, which was looted in 2003 but recouped by authorities at the Iraq Museum in Baghdad. The Morgantina acroliths have also returned close to home recently, on display since 2008 in Aidone, a town of about 6,000 inhabitants near Morgantina.

For the archeologist, art hist

orian, the regional and national governments, and the museum world, the Morgantina acroliths pose many questions:

- Why were statues made of marble only in the head, hands and feet?

- Who are the subjects or goddesses represented by the statues?

- How do we repatriate stolen goods? And do museums have the moral obligation to return items if they are later found to be looted?

- When back in their home location, how should the statues, with missing parts, be displayed?

These expressive faces charm us with their smiles . Marble–not as abundant in Sicily as in Greece–was limited to head, feet and hands. However, it is easy to see the Morgantina heads as comparable in style and date to the well-known Peplos Kore from Athens.c. 530 BCE. They could have been made later if made in a provincial location, such as Morgantina. (Morgantina is 126 km from Sircusa, the great city of Syracuse in Greek Sicily.) Unquestionably feminine, the Morgantina heads are very much alike, although one woman is clearly more mature than the other, giving us hints of their relationship.

Below, a Sicilian fashion designer has clothed the acroliths. Demeter has both her

hands and feet, while only one hand and foot belong to Persephone, also called Kore.

Demeter, goddess of grain, and her daughter, Kore, are the likely identities of the goddesses who sat in a sanctuary of ancient Morgantina. The particular honor given to these goddesses in Sicily was tied to mythology and to the island’s fertility, as the soil was less rocky and more fertile than in Greece. According to mythology, Hades of the underworld abducted Demeter’s daughter and caused deep pain. On a frantic search for Kore, the goddess of grain scorched the earth and let all vegetation die. Zeus promised the return of her daughter if she agreed to send her into the underworld for half of every year. For that reason, Kore, also called Persephone, goes underground every autumn. According to myth, Sicily, specifically Enna (Morgantina is in the province of Enna), was the site of Kore’s abduction. When Demeter brought her daughter back from the underworld and restored the grain, Sicily was the first place to which vegetation returned. Paying homage to Demeter and her daughter, goddess of the underworld, insured fertility of the land. The cult of Demeter and Kore was strong throughout ancient Sicily, with more sanctuaries dedicated to these goddesses than any other gods or goddesses.

The unfortunate stealing of Persephone into the underworld played itself out again in 1978, when professional tomb robbers dug up the acroliths and, through a network of dealers, sold them. A private collector, perhaps unaware that the marbles were obtained illegally, paid $1,000,000 for the goods. Through a laborious process of tracking down what happened to the acroliths, as well as other stolen items from Morgantina, Professor Emeritus Malcolm Bell of the University of Virginia pursued the goal of returning them to their region of origin. The collector gifted the marbles to the University of Virginia Art Museum with the knowledge they would eventually go back to Sicily. The problem of repatriating stolen goods has been a difficult one for American museums to address in recent years.

Demeter the mother, left, and her daughter, Persephone (also called Kore), right

The goddesses now sit together in their own room, like a cult chamber, in the Aidone Archeological Museum. The artful display has special lighting and new armatures and clothing designed by a fashion designer from Sicily, Marella Ferrara. The goal is to make the display as authentic as possible, giving the public an impression as they may have appeared in ancient times. (I still wonder if Demeter was holding sheaths of wheat? Kore holding a pomegranate?) Gauze-like coverings are suggestive but not definitive of how the statues may have been in a cult sanctuary. We can once again witness the mysteries of Demeter and Persephone in a space about 2 km from their original home.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Mar 6, 2010 | Lorado Taft, Memorials, Sculpture

Before many monuments arrived on the national Mall in Washington, DC, the Adams Memorial in Rock Creek Cemetery was a major tourist attraction in the capital city. Because of its fame, I decided to visit it. I compared this monument to a tomb by Lorado Taft in Chicago, because I have always been quite moved by Taft’s Solitude of the Soul at the Art Institute of Chicago.

The Adams Memorial is a seated bronze figure with an androgynous face and deep, textured drapery. Augustus Saint-Gaudens completed it in 1891. Its green patina and mottled effect beautifully contrast with the speckled pink granite base and block designed by architect Sanford White. By comparison, Lorado Taft’s sculpture, erected in 1909, is starker; it takes the memorial concept further into 20th century abstraction.

Henry Adams, a 19th century historian and novelist, commissioned the Adams Memorial after his wife, Clover Hooper Adams, committed suicide in 1885. An amateur photographer of some note, Clover had suffered from depression before swallowing potassium cyanide, a chemical used in developing her photographs. Saint-Gaudens planned and executed the sculpture over 5 years. He loosely based the statue on Clover’s appearance, the iconic qualities of Buddhist statues and the grandeur of Michelangelo, particularly his Sibyls on the Sistine Ceiling, striving to capture an eternal presence in a figure that will never be alive to Adams, or us, again.

Saint-Gaudens entitled this work the The Mystery of the Hereafter and the Peace of God that Passeth Understanding, but the public called it “Grief,” a term Henry Adams never accepted. Adams, a grandson and great-grandson of US Presidents, was buried here when he died in 1918.

As I see it, the statue expressed Henry Adams’ need to come to terms with his wife’s death, an event about which he avoided speaking or writing. Yet the loss deeply affected him and whether there was guilt, regret or other unresolved feelings, he seems to have used the monument to make peace with those feelings. The intention was

to express a state of being which is neither joy nor anguish. The memorial avoids ideas about judgment and the hereafter, but evokes concepts of the divine feminine. Adams visited this grave statue often, but never met the state of peace the image portrays. (Yet the powerful female spirit appears to have influenced him long afterwards, as revealed in his books, The Education of Henry Adams and Mont Saint-Michel and Chartres.)

to express a state of being which is neither joy nor anguish. The memorial avoids ideas about judgment and the hereafter, but evokes concepts of the divine feminine. Adams visited this grave statue often, but never met the state of peace the image portrays. (Yet the powerful female spirit appears to have influenced him long afterwards, as revealed in his books, The Education of Henry Adams and Mont Saint-Michel and Chartres.)

The bronze figure, its face and strong hands are powerfully reminiscent of Michelangelo. The drapery is very heavy, but the woman’s face is not covered. She raises an arm and hand to intercept the veil, emphasizing that face. The eyes appear closed at first glance, but are actually open, looking downward. An earthly existence is vanishing but still present, as Henry Adams tried to keep her. And she is present to us in a timeless way, since the Saint Gaudens’ statue tries to avoid the finality of loss so pervasive in the statues of Lorado Taft.

Eternal Silence

Eternal Silence is the appropriate name Lorado Taft gave the grave marker of Dexter Graves in Graceland Cemetery, Chicago. A heavily draped bronze figure pulls his robe over his mouth, snuffing out his presence in the world. Note that a hand deliberately covers the mouth, in contrast to the Adams’ figure whose hand opens the veil like a curtain to reveal a face. Here the individual portrait is completely irrelevant; he is representative of an eternal truth, the finality of a life. Eyes are closed and, like most of the face, they are blackened.

Taft prefers broad, bold simplified shapes in sculpture, as opposed to the Adams Memorial’s more nuanced drapery folds. The bronze’s patina is a light green, in contrast to the black face. A nose pops out under the hood–also green. It’s spooky. No wonder many tales about ghosts have come from those who have visited the statue. For the record, Dexter Graves died in 1844, after he had come to Chicago from Ohio with 12 other founding families of the city in the 1830s. He built a hotel in Chicago and his son Henry commissioned the monument in 1907.

The statue and sky reflect behind into black granite, the

same material used in the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial. Taft simplified the outer garment, barely suggesting a large masculine physique underneath. The figure stands erect, his silencing complete.

same material used in the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial. Taft simplified the outer garment, barely suggesting a large masculine physique underneath. The figure stands erect, his silencing complete.

Taft — like Michelangelo and Rodin — was committed to using the human figure to express the greatest truths as he saw it, even if his ideas were quite abstract.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 10, 2010 | Lorado Taft, Memorials, Sculpture

The Black Hawk Memorial stands nearly 50 feet tall and rises on a 77 foot bluff above the Rock River in Oregon, IL. It pays homage to the Chief of the Fox and Sauk tribes who fought against the United States in the War of 1812. Lorado Taft designed the statue in 1908, long after the memory of this chief — who had controlled the region of the Mississippi and Rock Rivers until the 1830s — had vanished.

above the Rock River in Oregon, IL. It pays homage to the Chief of the Fox and Sauk tribes who fought against the United States in the War of 1812. Lorado Taft designed the statue in 1908, long after the memory of this chief — who had controlled the region of the Mississippi and Rock Rivers until the 1830s — had vanished.

Taft sheathed him in a blanket and simplified his form to focus on the face. The main ingredient is concrete, an interesting contrast to the wild environment, and to the more radiant granite and bronze of tomb memorials. Using a hollow core and iron tie rods, Taft and his student John Prasuhn created a broad sweeping column for the body leading up to the sad, heroic face.

Black Hawk died in 1838 and Native American culture also died, a fact not lost on Taft when he chose a generalized face rather than a likeness of Black Hawk. Taft considered this statue is the Eterna l Indian, symbolizing grief on a monumental scale. The artist knew deep sadness continually resonates and he did not attempt to pacify its presence.

l Indian, symbolizing grief on a monumental scale. The artist knew deep sadness continually resonates and he did not attempt to pacify its presence.

Simultaneously, he was working on

Eternal Silence, a commission for Dexter Graves’ tomb 100 miles away in Chicago.

Black Hawk was Lorado Taft’s own inspiration on the site owned by Eagles’ Nest Art colony he had founded in 1898. When his funds ran short, the state of Illinois paid for the statue’s completion in 1911.

Chief Black Hawk lost his land and was forced to move to Oklahoma in 1831, a resettlement which made it

possible for Graves and 12 other founding families to move to Chicago from Ohio. The artist must have known this irony when he was creating the statues. The memory of Black Hawk looms much larger and more specific than the memory of Graves; he commands a part of the environment.

possible for Graves and 12 other founding families to move to Chicago from Ohio. The artist must have known this irony when he was creating the statues. The memory of Black Hawk looms much larger and more specific than the memory of Graves; he commands a part of the environment.

Lorado Taft possessed a grand vision–equal to Black Hawk’s, for his students and art, but his reputation as a sculptor seems to be regional. An influential writer and teacher at the Art Institute, he made a large Fountain of Time near the University of Chicago, The Blind at the University of Illinois in Urbana, and the Columbus Monument at the Union Station in Washington. An online group follows his work.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

hair held down on the scalp are characteristic of both statues. The Mozia youth’s capped hair ends in ringlets, an atypical feature, but not without parallels. It’s unfortunate the center of this figure’s nose, mouth and chin are no longer visible in their original form for a perfect comparison.

hair held down on the scalp are characteristic of both statues. The Mozia youth’s capped hair ends in ringlets, an atypical feature, but not without parallels. It’s unfortunate the center of this figure’s nose, mouth and chin are no longer visible in their original form for a perfect comparison.

he statue may be something the charioteer himself erected to honor his victory, and placed it at home in Sicily, rather than in a sanctuary dedication on the mainland of Greece. (These details are explained by Professor Bell, who suggests it was made by a Greek artist for a victorious Sicilian charioteer patron.)

he statue may be something the charioteer himself erected to honor his victory, and placed it at home in Sicily, rather than in a sanctuary dedication on the mainland of Greece. (These details are explained by Professor Bell, who suggests it was made by a Greek artist for a victorious Sicilian charioteer patron.)

ures, less elongated than the Kritios Boy or the Charioteer at Delphi. So questions of his “Greekness” should be eliminated.

ures, less elongated than the Kritios Boy or the Charioteer at Delphi. So questions of his “Greekness” should be eliminated.

same material used in the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial. Taft simplified the outer garment, barely suggesting a large masculine physique underneath. The figure stands erect, his silencing complete.

same material used in the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial. Taft simplified the outer garment, barely suggesting a large masculine physique underneath. The figure stands erect, his silencing complete.

possible for Graves and 12 other founding families to move to Chicago from Ohio. The artist must have known this irony when he was creating the statues. The memory of Black Hawk looms much larger and more specific than the memory of Graves; he commands a part of the environment.

possible for Graves and 12 other founding families to move to Chicago from Ohio. The artist must have known this irony when he was creating the statues. The memory of Black Hawk looms much larger and more specific than the memory of Graves; he commands a part of the environment.

Recent Comments