by Julie Schauer | Nov 28, 2012 | Architecture, Christianity and the Church, Mosaics, Sculpture, Sicily, The Middle Ages

|

Sicily was controlled or settled at various times by Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Saracens,

Normans and Spaniards. This view is Monreale, in the north, east of Palermo. |

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

|

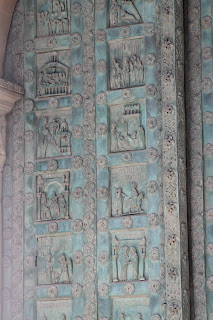

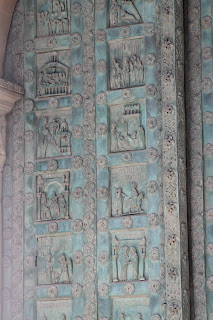

Bonnano of Pisa cast the bronze doors

in 1185 |

A Norman ruler, William II (1154-89), built Monreale Cathedral between 1174 and 1185. When the Roman Empire first became Christian, Sicily reflected the ethnic Greeks who lived on the island. In the 8th century, Saracens conquered Sicily and held it for two centuries, although a majority of residents were Christians of the Byzantine tradition. William the Conqueror’s brother Roger took over the island in 1085, but allowed the other groups to live peacefully and practice their religion. Normans, Lombards and other “Franks” also settled on the island, but the Norman rule between the late 11th and late 13th centuries was quite tolerant. By the 13th century, most residents adopted the Roman Catholic faith. Germans, Angevins and finally, the Spanish took control of the island.

|

This pair of figural capitals in the cloister could be a biblical

story such as Daniel in the Lion’s Den or even a pagan tale |

Monreale Cathedral was built on a basilican plan in the Romanesque style that dominated Western Europe in the 12th century, although the Gothic style had already taken hold in Paris at the time of this building. It is based on the longitudinal cross plan with a rounded east end. Two towers flank the facade. (This Cathedral ranks right up with Chartres and Notre-Dame of Paris, as one of the world’s most beautiful churches.)

|

Capitals feature men, beasts and beautiful

acanthus leaf designs |

In the artistic and decorative details, there is great richness. The portal has one of the few remaining sets of bronze doors from the Romanesque period. These doors were designed and cast by a Tuscan artist, Bonanno da Pisa. A cloister, similar to the cloisters of all abbey churches has a beautiful courtyard with figural capitals. Its pointed arches betray Islamic influence. The sculptors who carved the capitals are thought to have come from Provence in southern France, perhaps because of similarity in style to abbey churches near Arles and Nîmes, places with a strong Roman heritage. However, on the exterior apse of the church is a surprise. It has the rich geometry of Islamic tile patterns. Islamic artists who lived in the vicinity of Monreale were probably called upon to do this work.

|

| Islamic artisans decorated the eastern side of the church with rich geometric patterns |

The Greek artists who decorated the Cathedral’s interior were amongst the finest mosaic artists available. The Norman ruler may have brought these great artisans from Greece. Monreale Cathedral holds the second largest extant collection of church mosaics in the world. The golden mosaics completely cover the walls of the nave, aisles, transept and apse – amounting to 68,220 square feet in total. Only the mosaics at Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey, cover more area, although this cycle is better preserved. The narrative images gleam with heavenly golden backgrounds, telling the stories of Biblical history. The architecture is mainly western Medieval while imagery is Byzantine Greek.

|

| Mosaics in the nave and clerestory of Monreale Cathedral |

A huge Christ Pantocrator image that covers the apse is perhaps the most beautiful of all such images, appearing more calm and gentle than Christ Pantocrator (meaning “almighty” or “ruler of all”) on the dome of churches built in Greece during the Middle Ages. The artists adopted an image used in the dome of Byzantine churches into the semicircular apse behind the altar of this western style church. Meant to be Jesus in heaven, as described in the opening words of John’s gospel, the huge but gentle figure casts a gentle gaze and protective blessing gesture over the congregation. He is compassionate as well as omnipotent.

|

Christ Pantocrator, an image in the dome of Greek churches, spans the apse

of this western Romanesque church. |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Mar 6, 2011 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Mosaics, Roman Art, Sicily

In the huge Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Armerina, Sicily, a girl is can be seen through the corridor………………..not one, but the room has 10 of these bikini girls engaged in some athletic activities. They are made of pieces of finely cut stone, set into mortar for a smooth finish on the floor. Mark Schara took these photos of the largest series of floor mosaics in the Roman Empire.

In the huge Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Armerina, Sicily, a girl is can be seen through the corridor………………..not one, but the room has 10 of these bikini girls engaged in some athletic activities. They are made of pieces of finely cut stone, set into mortar for a smooth finish on the floor. Mark Schara took these photos of the largest series of floor mosaics in the Roman Empire.  Their games include the discus throw, weight lifting and ball tossing. One with a palm and crown may be a winner.

Their games include the discus throw, weight lifting and ball tossing. One with a palm and crown may be a winner.

From the mosaics in ancient Sicily we can trace the art of stone floor mosaics, backwards. Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Amerina, covered by a landslide in the 13th century but now uncovered, has the largest group of extant mosaics from the Roman world. The cut marble stones decorated floors, not walls, of the palace. It is not known who built or owned the huge villa in the early 4th century, but it may be connected to the emperors, or gladiators in the late Roman Empire. There are several mosaics of giant figures and animals, representing diverse subjects like the Labors of Hercules, hunting and children fishing. One of the most surprising subjects is a group of young women, bikini girls. The floors of the entire villa are covered with remarkable picture puzzles.

Also at Villa Romana del Casale is the Room of Fishing Cupids. The children appear quite young and have curious markings on their faces .

At nearby Morgantina, three excavated homes have floor mosaics from the 3rd century BCE, some 500 years earlier than the Villa in Piazza Armerina. Above is a mosaic in the House of Ganymede, perhaps the earliest mosaic cut into cubes. Ganymede is being abducted by Zeus’ eagle, and the Greek key pattern in the border creates an optical illusion of shifting perspective patterns.

At nearby Morgantina, three excavated homes have floor mosaics from the 3rd century BCE, some 500 years earlier than the Villa in Piazza Armerina. Above is a mosaic in the House of Ganymede, perhaps the earliest mosaic cut into cubes. Ganymede is being abducted by Zeus’ eagle, and the Greek key pattern in the border creates an optical illusion of shifting perspective patterns.

Although we normally associate mosaics with the Byzantine wall mosaics in churches, the Hellenistic Greeks and Romans used them extensively. From Hellenistic times, three homes with mosaics have been excavated in Morgantina. Of special note is a mosaic in the House of Ganymede, made of marble and very finely executed, suggesting the wealth of central Sicily before the Roman takeover in 211 BCE. The House of Ganymede may, in fact, have the earliest mosaics found to be cut into squarish tesserae, the standard “tesselated” form for Roman and Byzantine mosaics. The best guess for a date is 250 BCE. It may copy a painting.

An animal mosaic from the Punic island of Mozia is the earliest known floor mosaic, perhaps from the early 4th century BCE. Composed of only gray, black and white pebbles, it was made before the famous pebble mosaics of Pella, Greece, from about 300 BCE.

An animal mosaic from the Punic island of Mozia is the earliest known floor mosaic, perhaps from the early 4th century BCE. Composed of only gray, black and white pebbles, it was made before the famous pebble mosaics of Pella, Greece, from about 300 BCE.

The oldest known floor mosaic is in Mozia, the small Punic island adjacent to Marsala, Sicily, which was conquered by Greeks in 397 BCE. In the House of the Mosaic, there is a floor carpet of real and imagined animals composed of black, white and gray pebbles. It lacks color and looks rough compared to later mosaics of both pebble and cut stone. Its border patterns — the Greek key, palmettes and waves — definitely look Greek. Does it come from shortly after the Greek conquest of 397 BCE? or even earlier?

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 25, 2011 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Architecture, Greek Art, Mythology, Sicily

In Selinunte, Sicily, the remains of several Greek temples from the 6th- 5th century

In Selinunte, Sicily, the remains of several Greek temples from the 6th- 5th century

BC can reveal much about temple construction, although they fell to Carthaginian invasions and earthquakes not long after their building. Architect Mark Schara,

with his good eye for detail, took almost all of these photos.

Temple E has most of its outer colonnade, the peristyle, restored.Classical harmony is apparent in the rhythm of fluted columns, continuing up into the triglyphs raised to the sky.

.

But many of the capitals have fallen. On the ground level, we can appreciate their large scale.

But many of the capitals have fallen. On the ground level, we can appreciate their large scale.

Temple F was badly damaged. Much of the white stucco facing for the fluted limestone column on right is still visible.

Temple G, below, was the largest of the 7 temples of Selinunte, the ancient city of Silenus.

This temple had columns about 54 feet tall. Here, we see the columns were made of individual segments called drums, each of which are 12 feet high

This temple had columns about 54 feet tall. Here, we see the columns were made of individual segments called drums, each of which are 12 feet high.

The overturned capitals, echinus on top of the abacus, has an 11′ diameter. Here, the abacus and echinus were carved in one piece, unlike above at Temple E.

At the time of destruction, not all of the capitals had been fluted. Thus we

know that the temple was never completed

Nearby in Agrigento, the ancient city called Akragas, had a series of ten temples in the Valley of the Temples.

The Temple of Concord is one of the best preserved Doric temples.

It had been converted into a church in the early Christian period.

In the 8th -3rd centuries BCE, Sicily was a battleground between Greeks who settled 3/4 of the island and Carthaginians who settled the western portion; then it became the target of Roman conquest.

Though only a small portion of the peristyle remains, the

Though only a small portion of the peristyle remains, the

Temple of Hera was in better condition than most of these temples

which fell victim to Carthaginian destruction, then earthquakes.

But an even taller temple to Olympian Zeus would have been the largest of Doric Greek temples, the height of a 10-story building; it was incomplete when the disaster struck.

Construction began in 480 BCE and was still in progress when it was decimated in 407 BCE. The Telemon or Atlas figures whose bent arms support the architravemay in fact represent Carthaginian prisoners who had been made to build the temple.

Construction began in 480 BCE and was still in progress when it was decimated in 407 BCE. The Telemon or Atlas figures whose bent arms support the architravemay in fact represent Carthaginian prisoners who had been made to build the temple.  But even these giants, who appear to have held up the building, have fallen,

But even these giants, who appear to have held up the building, have fallen,

struck down by the Carthaginians who conquered Akragras.

Only a replica of one of the ruined giants remains on the site.

Ancient Akragas may have had 200.000 people in the 5th century BCE.Today we witness the fallen giant as a symbol of human pride grown too large,

Ancient Akragas may have had 200.000 people in the 5th century BCE.Today we witness the fallen giant as a symbol of human pride grown too large,

and, consequently, fallen.Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by admin | Feb 25, 2011 | Architecture, Art and the Environment, Sicily, The Greek World

In Selinunte, Sicily, the remains of several Greek temples from the 6th- 5th century BC reveal much about temple construction, although they fell to Carthaginian invasions and earthquakes not long

In Selinunte, Sicily, the remains of several Greek temples from the 6th- 5th century BC reveal much about temple construction, although they fell to Carthaginian invasions and earthquakes not longafter their building. Temple E has most of its outer colonnade, the peristyle, restored.Classical harmony is apparent in the rhythm of fluted columns, continuing up into the triglyphs raised to the sky.

Architect Mark Schara, with his good eye for detail, took almost all of these photos.

.

But many of the capitals have fallen. On the ground level, we can appreciate their large scale.

But many of the capitals have fallen. On the ground level, we can appreciate their large scale.

Temple F was badly damaged. Much of the white stucco facing for the fluted limestone column on right is still visible.

Tem

ple G, below, was the largest of the 7 temples of Selinunte, the ancient city of Silenus.

This temple had columns about 54 feet tall. Here, we see the columns were made of individual segments called drums, each of which are 12 feet high

This temple had columns about 54 feet tall. Here, we see the columns were made of individual segments called drums, each of which are 12 feet high.

The overturned capitals, echinus on top of the abacus, has an 11′ diameter. Here, the abacus and echinus were carved in one piece, unlike above at Temple E.

At the time of destruction, not all of the capitals had been fluted. Thus we

know that the temple was never completed

Nearby in Agrigento, the ancient city called Akragas, had a series of ten te

mples in the Valley of the Temples.

The Temple of Concord is one of the best preserved Doric temples.

It had been converted into a church in the early Christian period.

In the 8th -3rd centuries BCE, Sicily was a battleground between Greeks who settled 3/4 of the island and Carthaginians who settled the western portion; then it became the target of Roman conquest.

Though only a small portion of the peristyle remains, the

Though only a small portion of the peristyle remains, the

Temple of Hera was in better condition than most of these temples

which fell victim to Carthaginian destruction, then earthquakes.

But an even taller temple to Olympian Zeus would have been the largest of

Doric Greek temples, the height of a 10-story building; it was incomplete when the disaster struck.

Construction began in 480 BCE and was still in progress when it was decimated in 407 BCE. The Telemon or Atlas figures whose bent arms support the architravemay in fact represent Carthaginian prisoners who had been made to build the temple.

Construction began in 480 BCE and was still in progress when it was decimated in 407 BCE. The Telemon or Atlas figures whose bent arms support the architravemay in fact represent Carthaginian prisoners who had been made to build the temple.  But even these giants, who appear to have held up the building, have fallen,

But even these giants, who appear to have held up the building, have fallen,

struck down by the Carthaginians who conquered Akragras.

Only a replica of one of the ruined giants remains on the site. Ancient Akragas may have had 200.000 people in the 5th century BCE.Today we witness the fallen giant as a symbol of human pride grown too large,

Ancient Akragas may have had 200.000 people in the 5th century BCE.Today we witness the fallen giant as a symbol of human pride grown too large,

and, consequently, fallen. by Julie Schauer | Feb 21, 2011 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Architecture, Sicily

(Thanks to Mark Schara for the use of his photographs)

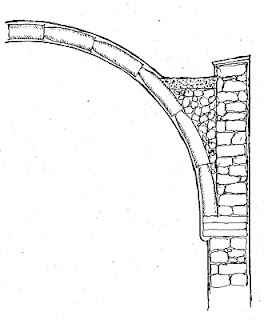

The North Baths of Morgantina, in east central Sicily, date to the 3rd century BCE and may in fact represent the earliest dome that has been excavated in the ancient Mediterranean world. Like everything in the buried settlement of Morgantina, it was built before the Roman conquest in 211 BCE. This new evidence suggests that Hellenistic Greeks, not Romans, invented the first dome. However, unlike the concrete used by Romans to make domes, the construction material would have been terra cotta tubes found on the site; the sizes and formation of these tubes suggest they were used to make a domed space.

Public baths were a staple of the ancient towns and cities. Morgantina was a small settlement and the dimension of its baths are modest. Yet the roofing of the North Baths structure appears very significant. Two oblong rooms and one circular room were found to have curved ceilings made of these interlocking tubes, held together inside and out by plaster. They would have formed perfect arches when fit together, and each arch when placed in parallel alignment with other arches forms either a barrel vault or dome. There were two barrel vaulted rooms and one with a dome.

This method was also used in

the Roman baths of North Africa in the 3rd century CE, while builders in Rome were using concrete. The Morgantina baths are at least 4 centuries earlier than the others of this technique and predate Roman concrete vaults and domes by about a century.

Interlocking cotta tubes made in the Hellenistic settlement of Morgantina were

fit into each other to form arches. Arches placed adjacent to each other could form a dome, above, or barrel vaults, with masonry reinforcement as shown on the right.

Although some excavation began in the early 1900s, archeologists identifed Morgantina as the archeological site in 1958 using coins. The place had been described by Strabo and some early Roman writers, but it was abandoned by the end of the first century CE. Originally a Sikel settlement, it was occupied by Greeks in the 5th century BCE, conquered by Rome in 211 BCE and consequently taken over by Spanish mercenaries of Rome. In addition to baths, Morgantina has an agora, a theatre, graneries, an ekklesiesterion, several sanctuaries, homes with mosaics and two kilns which have been excavated.

An overview of Morgantina reveals the Greek theatre and other excavation structures.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 16, 2011 | Ancient Art, Greek Art, Sculpture, Sicily

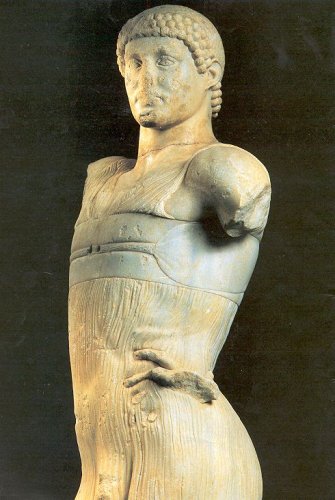

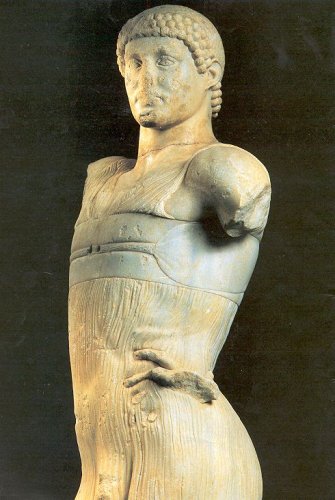

This tall elegant Charioteer of Mozia or “Giovane of Mozia,” was excavated in

1979. It brings up problems of identity, meaning and dating in Greek Art.

A life-size statue was dug up in 1979 in Mozia, ancient Motya, a tiny island adjacent to the west coast of Sicily. The slightly larger than life-size Youth of Mozia demonstrates why it is necessary for art historians to constantly re-evaluate conceptions of style, meaning and dating in art. Everyone agrees it belongs to the 5th century BCE, and, based on exact location of the find and the layer in which it was buried, it cannot be later 397 BCE. Yet Mozia was a Carthaginian settlement and the Carthaginians were constantly at war with Greeks who controlled most of Sicily. The questions are:

* Who is the subject?

* What is the date?

* Where was it made?

* Why did it end up in Mozia?

This statue has physical beauty, elegance, grace and transparent drapery. Feet and arms are missing but remnants of one hand dig into the corresponding hip, a marvelous detail which only an artist of great skill could execute. Much of the face is damaged, perhaps intentionally. The head was detached but has been put back. Although Most experts agree that the statue is Greek dating to the 5th century BCE, some have claimed the hair and face appear non-Greek and perhaps Carthaginian.

Bent arms in opposite directions would have created a vigorous counterpoise, a surprise

considering the rigidity of some conventional aspects of the head and hair.

The pose, vigorous turn and thin, transparent drapery would suggest a classical date of 450-420 BCE. “Wet drapery” is

mainly a convention of female figures of this High Classical period or end of the 5th century BCE, as in the Parthenon goddesses or on the Temple of Athena Nike. Yet there are contraindications to a late 5th century date. Hair is very stylized, and therefore, Archaic, and the facial modeling is most akin to the Severe Style, 480-450 BCE. To get better idea of a date, we can compare to other Greek sculptures, and I will fill in a suggested idea of identity.

When I compare this beautifully carved wet drapery to other works, the strongest analogy is found to the Ludovisi Throne, probably representing the birth of Aphrodite. This relief, dated c. 460 BCE, is now in Rome, but is known to have been connected to an Ionian temple of Aphrodite in Locri, a far southern city in Italy. (Both Sicily and southern section of Italy were heavily Greek in the centuries before the Roman conquest.)

The Ludovisi Throne, usually dated to 460 BCE, comes from a Greek colony is

south Italy. It has similar “wet drapery.”

When I look at the profile, I’m reminded of the Kritios Boy, c. 480 BCE,

also in marble, although the Kritios Boy had inlaid eyes of another

material. Short stylized

hair held down on the scalp are characteristic of both statues. The Mozia youth’s capped hair ends in ringlets, an atypical feature, but not without parallels. It’s unfortunate the center of this figure’s nose, mouth and chin are no longer visible in their original form for a perfect comparison.

The profile of the Mozia marble reveals holes in the ear and even some bronze in the back of the head, perhaps an attachement for the victory wreath of a charioteer.

The Kritios Boy,below, is in better condition.

His eyes, missing, were inlaid with another, colored material.

The Charioteer of Delphi, c. 470 BCE, is bronze and has original inlaid eyes.

He is a victorious chariot driver from Sicily but was dedicated in Greece.

The bronze cast Charioteer of Delphi, c. 470 BCE, represented the winner of the Pythian games who came from the city of Gela in Sicily, but the statue was made in Greece and erected to Apollo in thanks for a victory Apollo at the god’s sanctuary in Delphi. He has copper inlays for lips and eyelashes, onyx for eyes and silver for the victory wreath, which fortunately remain intact. Yet the Delphi Charioteer, c. 470 BCE, is more rigid than our marble example and his face is mask-like. He was part of a bronze group composition, standing behind 4 horses and such stoic emotion was needed for the concentration of an athletic victor. (Remains of the horses, reins and the statue base with dedication are extant.)

The Mozia figure also wears a ankle-length chiton, the

xystis that all chariot drivers wore, although without sleeves and in a very light fabric. Besides the

xystis, there are other reasons that the Mozia youth can be considered a charioteer. His thick belt of a stiff material compares to the belted chests of charioteers seen on Sicilian coins dated to 460 BCE and later, an alternative to the Delphic Charioteer’s belt on the waist and back. Such belts or ties were necessary to keep the fabric from billowing in the wind and interfering during a race. Here we see large holes to which a bronze belt buckle must have been attached. Finally, holes in the head above the row ringlets held bronze nails, two of which remain, evidence of a victory wreath attached to the original statue. The right arm, missing, was probably raised to attach the wreath, while the left arm was bent nonchalantly where the remaining hand reaches below at the hip. T

he statue may be something the charioteer himself erected to honor his victory, and placed it at home in Sicily, rather than in a sanctuary dedication on the mainland of Greece. (These details are explained by Professor Bell, who suggests it was made by a Greek artist for a victorious Sicilian charioteer patron.)

The Kritios Boy, about 480 BCE right, is in the Severe Style.

He is slightly under 4 feet tall.

The statue from Mozia has a stonger

shift to his hips than the Kritios Boy.

The Kritios Boy was excavated with many other statues in the Acropolis of Athens in 1865. It is generally known to mark the transition from Archaic to Early Classical or the Severe Style, as its legs shift position and transfer weight into a counterpoise, the relaxed pose of contrapposto. Severe Style art from 480-450 BCE is known for its stoicism or a lack of facial emotion.

There is a youth from Sicily made around the same time as the Kritios Boy, the Ephebe of Agrigento. If we compare his face with the Mozia figure, we see the similarities, a serious demeanor with broad feat ures, less elongated than the Kritios Boy or the Charioteer at Delphi. So questions of his “Greekness” should be eliminated.

ures, less elongated than the Kritios Boy or the Charioteer at Delphi. So questions of his “Greekness” should be eliminated.

The Ephebe of Agrigento (ancient Akragas), left, comes

from Sicily and is dated around

the time of the Kritios Boy, above.

Why was the Mozia Charioteer, if made by a Greek for a Greek in the 5th century, found in Mozia? In a constant battle between Greeks and Carthaginians, with the major Greek cities being ravaged between 409 and 405 BCE, this prized statue would have been captured as war booty. If you have any thoughts of date or identity to add to this blog, please comment.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

Recent Comments