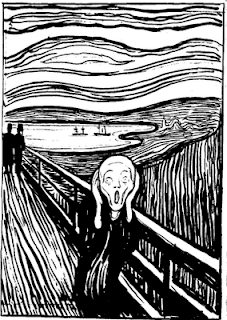

Edvard Munch’s The Scream is so powerful that the other works of this great Norwegian artist are overlooked. Other art by Munch articulated his feelings about the sad passages of life–sickness, death and breakups. Currently at The National Gallery of Art in Washington is an exhibition of Munch’s graphic art which represents many of the other themes he dealt with intensely, including illness, love, loss, and loneliness. The museum has pulled together prints from its own collection with images from two private collections to present a fuller view of the real artist. In fact, the sounds of silence in Munch’s work are as frequent and powerful as the voices of pain.

Edvard Munch’s The Scream is so powerful that the other works of this great Norwegian artist are overlooked. Other art by Munch articulated his feelings about the sad passages of life–sickness, death and breakups. Currently at The National Gallery of Art in Washington is an exhibition of Munch’s graphic art which represents many of the other themes he dealt with intensely, including illness, love, loss, and loneliness. The museum has pulled together prints from its own collection with images from two private collections to present a fuller view of the real artist. In fact, the sounds of silence in Munch’s work are as frequent and powerful as the voices of pain.

Munch also can be subtle. He explores the possibilities of images morphing into something else. In Waves of Love, we see a floating woman but don’t notice the man right away. Yet, when we discover him, the work becomes even more powerful.

A group of prints entitled The Kiss

can be seen as more harmonious symbols of love. One of these prints, an early intaglio example of The Kiss, is sensual in a idealized, classical form. You can see how it became a precursor to Munch’s symbiotic, unified idea of love in the woodcut versions, such as the one on the left, The Kiss IV of 1902. Here, Munch used different colors of ink and exploited the grain of wood to replicate the curves of the couple. Notice that the side view of “his” face is the front of “her” face. This print was certainly an inspiration for Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss–with its colors and mosaic patterns– much more popular and famous than Munch’s versions. Klimt borrowed Munch’s vertical emphasis and upward sweep of motion ending in the curving form of “oneness,” the back of a man’s head and the front of a woman’s face. In Munch’s version the man and woman’s face become one, a prelude to the unity of form that Constantin Brancu

can be seen as more harmonious symbols of love. One of these prints, an early intaglio example of The Kiss, is sensual in a idealized, classical form. You can see how it became a precursor to Munch’s symbiotic, unified idea of love in the woodcut versions, such as the one on the left, The Kiss IV of 1902. Here, Munch used different colors of ink and exploited the grain of wood to replicate the curves of the couple. Notice that the side view of “his” face is the front of “her” face. This print was certainly an inspiration for Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss–with its colors and mosaic patterns– much more popular and famous than Munch’s versions. Klimt borrowed Munch’s vertical emphasis and upward sweep of motion ending in the curving form of “oneness,” the back of a man’s head and the front of a woman’s face. In Munch’s version the man and woman’s face become one, a prelude to the unity of form that Constantin Brancu si used for his abstract rectangular block sculpture of The Kiss in 1910, where the eye of two becomes the eye of one.

si used for his abstract rectangular block sculpture of The Kiss in 1910, where the eye of two becomes the eye of one.

Klimt’s The Kiss shows the influence of Munch, above left

The beauty of seeing these graphic images is to see how he reworked themes over many years, changing the content as he made minor changes to the works. His prints are done in multiple colors and states, and vary in graphic techniques, from woodcut to etching, lithograph, aquatint and more. The Impressionists influenced his color and Van Gogh inspired his line, but he tried to reduce expressions even further than Van Gogh, making each of his images powerful symbols of human experiences.

Two Women on the Shore focuses on one central standing woman, with the seated person behind her — perhaps alluding to an elderly figure in her life, a ghost from her past, an alter ego, or a projection of whom she will become. Munch probably wished to evoke different viewpoints and we are likely to experience her differently depending on our individual conception. The colors changed a great deal from print to print, and this series of prints evokes variety of meanings. I am particularly fond of the way Munch repeatedly used a large bright symbol resembling the letter i — the sunlight or moonlight reflecting on water.

Often the power in Munch’s imagery comes from the push-pull effect of space: figures in front, space rushing behind, or figures in both places so we can’t help but be aware of the drama of their distance. Ashes explores the debris left over at the end of a relationship. Repeatedly, Munch used the figure in a landscape as a vehicle to summarize feeling. His women can be brash, his men often hurting.

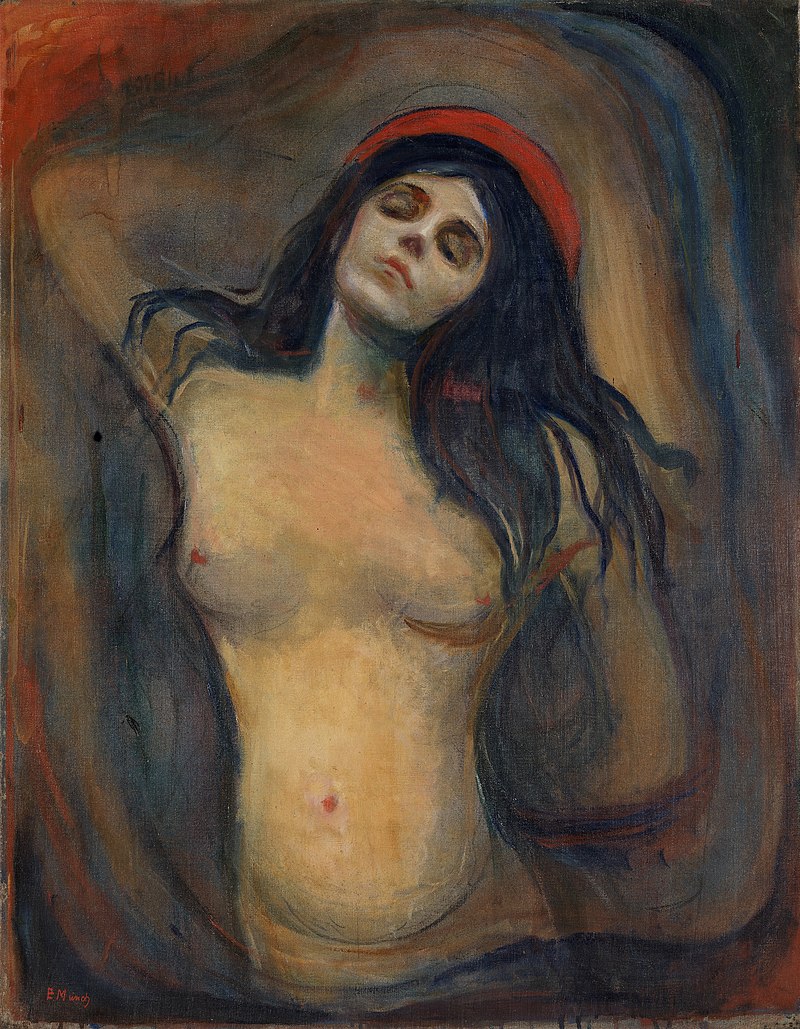

It’s likely that two of the great images of the early 20th century, Matisse’s Blue Nude and Picasso’s Les desmoiselles d’Avignon fell under the influence of Munch’s slightly earlier, unforgettable figures, the women in Ashes and Madonna. Some find Munch’s art too pessimistic; others say his art was less inspired after a breakdown at age 45 after which he gave up drinking.

Madonna

Excellent! You did a great job in opening other aspects of an artist who is perhaps too well know for doing only one thing.

Question, though: what is the significance of the use of the "i'?

Thomas Burchfield

The "i" is the moonlight on the water–the large dot being the moon and the stem being a reflection…..quite evocative if you think of nighttime on the fjords. A few years ago there was an exhibition at MoMA and so many of his paintings have this signature…I recently saw it in a painting of his, a Mermaid at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The exhibition has been extended until November 28th.