|

| Detail of “Olympia” by Edouard Manet, 1863, in Musée d’Orsay |

Victorine Meurent is Manet’s most frequent model of his early career. She shocked audiences as the indifferent courtesan in Olympia (above), exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1864. A year earlier, Victorine had scandalized Parisians, playing the part of a shameless woman who disrobed during a midday picnic. That was her role in Manet’s revolutionary painting, Le déjeuner sur l‘herbe(The Luncheon on the Grass– see on bottom) exhibited at the Salon des Refusées for the officially rejected paintings of that year. She is just the matter-of-fact figure that Manet wanted, and there is nothing beautiful, sexual or erotic in either image. In both paintings, she is not an individual but the object, the sexual object.

Manet also painted Victorine as Young Lady (also called Woman with a Parrot), in 1866. She looks taller in her long pink gown. There’s a magnificent unpeeled lemon on the ground. The symbols in the painting may allude to the five senses and suggest that she is a mistress. But she is a sympathetic one, one who even seems satisfied with her status as a mistress. However, it’s hard to see each of these paintings as representative of the same woman. One supposes that Victorine refused to model naked again, after all the attention of Olympia and Le déjeuner... had received.

|

| Manet, Young Lady, 1866, Metropolitan |

|

What was Manet’s relationship to Victorine? They could have met in the studio of Thomas Couture, Manet’s painting teacher. Born in 1844, Meurent started modelling there at age 16 and even may have taken lessons with Couture. According to her wikipedia biography, Victorine also played guitar and violin, and sang occasionally. She came from a family of minor artisans, and was probably not as poor as many painters’ models at that time.

|

| Manet, The Street Singer, 1862, Boston Museum of Fine Arts |

Manet’s first painting of her was The Street Singer. She looks shy, hurried and slightly guarded. Her brown dress is rumpled as she carried a guitar coming out of a building. She quickly grabs a bite to eat from the cherries in her napkin. Of all the paintings he did of her, this is perhaps the most revealing of Victorine, of who she was and what her life was to become. Artistic and musical, she worked hard.

Shortly after The Street Singer, he painted her portrait, Portrait of Victorine Meurent. She is pretty, resembling the photograph of her that Manet kept in his studio. She looks older than her 18 years in this painting, and she has an air of sophistication. Again she doesn’t resemble women modeled in Manet’s two early masterpieces of 1863, Olympia and Le déjeuner sur l’herbe.

|

| Manet, Portrait of Victorine Meurent, 1862, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

Manet must have loved her for her versatility, the fact she could appear quite differently from painting to painting. Her nickname was La Crevette, meaning “shrimp.” She was quite short and had red or auburn hair. Her eyes appear brown or hazel, while her hair can appear brown, red or of indeterminate color. In the portrait, he brought out all those qualities he saw in her as “beautiful.” Here, she also seems to be the real woman, the woman we see in the photograph collected by Manet. With Victorine as the subject, Manet did not objectify her at all!

|

| Manet, Mlle Victorine in the Costume of an Espada, 1862

|

However, most of the time, Manet pursued Victorine’s image for special effects. She is a prop, much like the fabrics, costumes and materials he kept in his studio. Mademoiselle Victorine in the Costume of the Espada is one of many paintings Manet did in a Spanish theme. Victorine is recognizable as the same woman as in Le déjeuner. (He painted this image a year earlier than Le dejeuner…) She is dressed like a bullfighter, and for the background Manet borrows from bullfighting prints by Goya. Manet was experimenting with raised perspective and compositional space, years before Van Gogh and Munch did the same. The pink cape she holds is study in painting fabric and color.

Was Manet being ironic by turning her into a bullfighter? Perhaps, but he also knew Victorine as a patient and willing model. He’s experimenting dramatically with both color and space here, and perhaps he didn’t have a male model up to task. Perhaps her small body best served his purpose.

My thoughts about Manet and Meurent’s relationship is that it was a strong, professional relationship. Was she his mistress? No. Like a good film director, Manet treated Victorine as the woman who could be cast in many roles. Victorine was to Manet as Diane Keaton was to Woody Allen’s early film career. Victorine was to Manet as Penelope Cruz was to Pedro Almodóvar. Later on, these film directors found other muses.

|

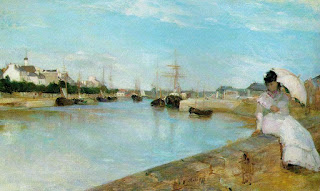

| Manet, The Railway (also called Gare Saint-Lazare), 1872, National Gallery of Art, Washington |

After a pronounced lull in painting Victorine after 1866, Manet painted her again in The Railway of 1872. At this time Victorine was 29, but she looked remarkably younger than she appeared in Olympia and Le Dejeuner. She is a woman who is nostalgic, a woman who looks to the past, while the girl beside her is all excited about the future. She is blasé about the train and wishes the future would not intrude so much into the present. Again, Victorine showed herself to be an actress who could play different roles — in her own standoffish way.

Victorine took up painting in the 1870s and she was accepted into the Salon at least 6 times. The only surviving painting is a portrait called Palm Sunday. It is quite good as a painting, but her style was far more traditional than Manet’s. She models the sitter with traditional, nuanced light and shade to make the face three-dimensional. The sitter turns to the side, which doesn’t really convey the personality. She even projects the plant closer to the picture plane and edge of the painting, giving it significant attention, too While Meurent frequently posed as prostitute, her only painting known today is of a young participant in a religious procession. Victorine was in her 40s by that time, but her choice of subject is ironic if we know of the types of paintings for which she posed.

|

| Victorine Meurent, Palm Sunday, 1885, Musée de l’art et l’histoire, Colombes |

After Manet died in 1884, Victorine went to Suzanne Leenhoff, Manet’s widow, and told her she had been promised more income from Manet as some of the paintings for which she modeled sold. Suzanne coldly refused her request.

Who was Victorine? She was essentially an honest woman, who made an honest living as a model. She worked hard in art and in music. She had minor successes from time to time, but fought back well when she hit hard times. Victorine sought artistic expression, but not fame or notoriety. Manet definitely wanted public affirmation, not the angry outcry that he was receiving while she was his muse. She modeled for other artists, including Toulouse-Lautrec, who teased her by calling her out as Olympia.

|

| Manet, Olympia, 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

Victorine may have been very interested in projecting Manet’s artistic objectives, but later pursued her own artistic objectives along different lines. (In Le déjeuner sur l‘herbe and Olympia, Manet sought to modernize the themes of Giorgione and Titian of the Renaissance. He remakes them to be of his time, in the style we call Realism.) The audiences who saw these masterpieces probably didn’t know the model‘s identity. They thought nudity portraying mythological themes of the Renaissance or in the guise of goddesses and muses was absolutely fine. Even portraying the prostitute could have been ok, if it had been done tastefully as in Goya’s Nude Maya. However, Victorine played the part too well, conveying the distasteful side of the world’s oldest profession–that she is treated as object, not person. She, herself, probably did not engage in sex for money, but she acted the part so well.

|

| Manet, Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1862-1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

Victorine is the symbol of a time and place. Although interwoven with the men, her frank stare seems to say to the audience, “I don’t give a damn what you think.” Is Manet judging like the 19th century audience did? More likely he recognizes the good and the bad. The advantage is that prostitution is a way to rise above one’s class and make a living. (Like the Valtesse de la Bigne, some women rose from abject poverty to the top of the social world this way.) The bad is the de-personalization that comes with it. My opinion is that Manet often found her to be the best model to make a statement of the ambiguities of modern life that he wished to express.

Throughout his career, Manet sought ways to reconcile the ambiguities of his time. Tomorrow will be Manet’s 185th birthday, and we’re still discussing the treatment of women. So today we witness the women’s march on Washington against the backdrop of Donald Trump’s Inauguration.

(There’s a 19th century French expression: “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” The more things change, the more they stay the same thing.) Please don’t get angry at me for saying it again.

Certainly other models, the actresses and actors of Manet’s oeuvre, also have the detached gaze. Such impersonal expressions went along with the modern, urban life. (Suzon, the barmaid in The Bar at the Folies–Bergère, says it just as well, or even better. But she came later.) Meurent channeled the expression better than almost anyone over time. As Manet’s first important muse, her soul lives on for posterity.

There arenovels about Victorine Meurent, none of which I’ve read: Paris Red, by Maureen Gibbon, Mademoiselle Victorine: A Novel, by Debra Finerman and A Woman with No Clothes, by V.R. Main. She has stirred the imagination of writers more than Manet and his relationship to Berthe Morisot, with whom he was in love. Manet even portrayed Berthe Morisot more often, and in more guises. I think it’s because Victorine took part in two of his three most famous paintings.

Here are three more blogs about Victorine Meurent and Manet.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments