The Last Missing Pieces of The Monuments Men

|

| Jan Van Eyck, Mary, part of the Deesis composition, detail of The Ghent Altarpiece in St. Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium, c. 1430 photo source: Wikipedia |

The Monuments Men is a true story about saving cultural artifacts in war. George Clooney has done a great job acting and directing this film which has an important message about art, what it means for us and the efforts some would go to save culture. One woman who played a huge part in saving art is shown and Cate Blanchett played that role with depth and finesse. An all-star cast doesn’t guarantee good reviews, but I often disagree with movie reviewers. Matt Damon, Bill Murray and Jean Dujardin star in the movie, too.

|

| Tourists in front of the Ghent Altarpiece in recent times. A film, The Monuments Men, explores its theft and recovery in World War II. Photo source: daydreamtourist.com |

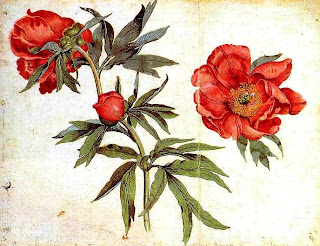

The star monument is Jan Van Eyck’s The Ghent Altarpiece, an example of one of the earliest oil paintings. (If students had seen the movie, they would have known it on a test, but the film was released only 5 days earlier and we had a snowstorm) In fact, the last missing part of the Ghent Altarpiece, was the panel of Mary, mother of Jesus from a Deesis grouping (an iconographic type western painters adopted from the eastern Orthodox Church). She is exquisitely beautiful and radiant. Van Eyck’s ability to visualize heavenly splendor and beauty in paint is astounding. I appreciate the film for showing how big the altarpiece actually is, and how a polyptych, of many panels, needed to be broken up into its parts to be moved. Actually, I wonder if Van Eyck and the patrons knew that using the polyptych format, rather than just a three-part triptych, would have its advantages in the time of war. Actually that painting has been the victim of crime 13 times and stolen 7 times, including the times of the Reformation, Napoleon and World War I.

|

| Michelangelo’s Bruges Madonna, the last work to be recovered, is under glass at the Church of Our Lady in Bruges. Photo source:Wikipedia |

The other star monument is Michelangelo’s Bruges Madonna, a free-standing sculpture the artist did shortly after The Pieta. It was the last and most precious piece to be found. The film makes an important point about the British man who insisted on protecting it during the war. I’m honored to have seen both monuments in their current homes and thank the determined people who sacrificed so much to do this for posterity. (I also love that the movie gives goes into the Hospital of Sint-Jans in Bruges and gives good views of the medieval cities of Bruges and Ghent, even in the night time. Thanks for acknowledging to what these places represent to earlier European culture.

Much of the film is about uncovering the mysteries, as well as anticipating the need for protection. It has both comic and tragic elements, as we watch injury and death and the dangers that common to all war. Not all paintings were saved, however. Some works ended up in Russia after the war and are still there. Picassos and Max Ernst paintings, even in German hands, were determined to be decadent and burned. The movie showed a Raphael portrait of a young man that has never been found.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine, c. 1490, is a portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, and an early work of Leonardo. It’s in the Czarytorski Museum in Krakow Photo source: Wikipedia |

Among the paintings captured by the Nazis, saved and uncovered by the rescue team of Americans, French and English were: a Rembrandt portrait, a Renoir, a Van Gogh, Manet’s In the Conservatory and Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine which had been taken from Krakow, Poland. Most of these paintings were shown to be hidden in underground mines. I’ve checked a little bit into the history of each of these and found that the Leonardo had been hidden in a castle in Bavaria. The Nazis stole the Manet from a museum in Berlin, and it’s not clear to me why they would do that unless it was planned to be in Hitler’s own museum.

The movie may have intentional inaccuracies. It also looked like a poor replica of Leonardo’s Ginevre de’ Benci was in the movie, and I am not sure if that could be accurate. That painting, as far as I know, already had been in the Mellon Collection that became part of the National Gallery.

There is much more to the story, I know, because Italy was allied with Nazis during most of the war and those works of art needed to be protected, too. At the point of action where the movie had started, most of the works in France had already been protected. The Monuments Men deals mostly with works in Belgium and the Netherlands.

Robert Edsel wrote the book that is the basis for the movie. I certainly hope to read it now, as well as another followup book he published last year, Saving Italy.

|

| Edouard Manet, In the Conservatory, 1879, Altes Museum Berlin Photo: Wikipedia |

Recent Comments