by Julie Schauer | Aug 24, 2015 | 19th Century Art, Degas, Gustave Caillebotte, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Monet, National Gallery of Art Washington, Paul Durand-Ruel, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Seurat

|

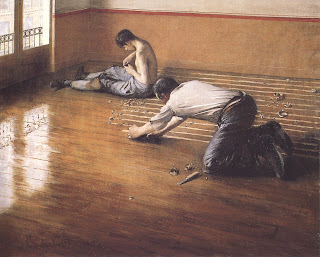

Gustave Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers, 1875 Musée d’Orsay, now on view

at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, |

Right now the National Gallery is having an exhibition of an Impressionist whose reputation has grown over the last 25 years, Gustave Caillebotte. Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye will be on view until October 4.

Caillebotte’s first masterpiece, The Floor Scrapers, was rejected by the Salon in 1875, but accepted into the Impressionist group exhibition the next year. He repaid his dear friends by buying up many of their works and then donating them to the French state after he died. Today many of those paintings belong to Paris’ great early modern museum, Musée d’Orsay.

There are so many reasons The Floor Scrapers is my favorite work by Caillebotte. The composition is extraordinarily well balanced with artful asymmetry on a tilted floor plane. (The invention of photography encouraged artists to look through the viewfinder and frame pictures differently.) There’s also the dignity given to labor, the working man and his beautiful anatomy.

Most it’s incredible to see how Caillebotte painted tactile contrasts on wood in the various stages of sanding, what looks like with or without varnish, and in the light and shadow. Caillebotte painted with more definition and precision than other Impressionists. Yet he illuminates the floor with natural light from the window and we see a wonderful scintillating values, colors and textures. Yellow shines through with touches of blue, but in the distance everything becomes an earthy brown color.

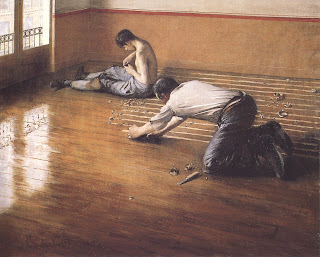

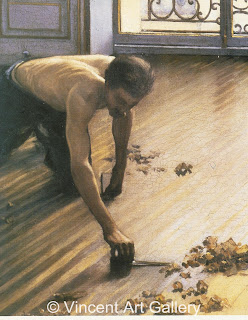

Caillebotte painted another floor scrapers

To understand how good this painting actually is, it’s useful to compare it with another version of floor scrapers that he did. It’s a simpler composition from a different angle, with fantastic lighting effects. Enlarging the photo here will really show off the reflections on the floor. (It isn’t in the National Gallery’s show, but was also part of the 2nd Impressionist exhibition in 1876.)

|

| Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers |

Many of Caillebotte’s other paintings in the exhibition also convey his artful sense of perspective: Le Pont de l’Europe, 1876, for example. He lived at the time that Paris had just experienced a massive rebuilding campaign of boulevards. Paris, A Rainy Day gives an impressive viewpoint of how the new city must have looked to the public, in the eyes of a new bourgeoisie class. Since streets corners were set up in star patterns, the linear perspective goes very deep into multiple vanishing points. A more famous artist, Georges Seurat, borrowed from the composition of Paris: A Rainy Day when he did his iconic painting of Paris on a sunny day, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte.

Other artists of the same time

Monet and Van Gogh are other who shared Caillebotte’s love of deep perspective space. Degas went even further than Caillebotte to exploit the unusual viewpoint. His work can be seen in an important Impressionist exhibition is in Philadelphia, Discovering the Impressionists, until September 13. The exhibit showcases Paul Durand-Ruel, the art dealer who took a gamble and went into great financial risk by buying up Impressionist painters because he believed in them. The exhibit includes Monet’s beautiful Poplars series. However, one of the really important works in the group is by Degas, The Dance Foyer at the Opera on the rue Le Peletier.

|

Edgar Degas, The Dance Foyer at the the Opera on the rue Le Peletier, 1872,

Musée d’Orsay, Paris, now on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art |

Comparing Caillebotte’s Men to Degas’ Dancers

This panoramic ballet scene of dancers offers a wonderful comparison with the Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers. This painting is also asymmetric and appears to look spontaneous, while it is actually exceptionally well-planned. Degas offers more layers of observation: into another room and out the window, through a mirror (?) or another room in the back center. We imagine that the major source of light is a an unseen window to the right. Whites and golds predominate the scene, with touches of blue and orange. Degas’s dancers, though quite strong, may seem delicate next to Caillebotte’s muscular workers.

In truth, Degas’ dancing girls and Caillebotte’s hard-working men are much the same. Their work is a labor of love, as the Impressionists saw it. The same can be said about Caillebotte, Degas, Durand-Ruel and those who left us with a wonderful record of life in Paris in the 1870s. The ballet painting was done in an opera house that destroyed by fire the very next year, probably caused by gaslights.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2024

by Julie Schauer | Mar 18, 2013 | 19th Century Art, Art Appreciation: Visual Analysis, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Landscape Painting, Monet, Musee d'Orsay, The Art Institute of Chicago

|

| Claude Monet, The Road to Giverny in Winter, sold last year, but hadn’t been seen in public since 1930 |

When Monet’s The Road to Giverny in Winter came up at auction about a year ago, it was the first time this idyllic painting had been on the art market since 1924. The painting leaves me with a magical impression, in the way Monet painted a pink sunset with warm highlights poking through the winter chill. Leave it Monet to see the beautiful warmth in the coldness of winter. So I wanted to explore his other paintings of snow and see how he developed the theme. At one point in the late 1870s, Monet’s colleague Manet tried to paint a scene of snow, but gave up, exclaiming that no one could do it like Monet.

When looking at reproductions online, we get a great variety of versions of the colors in the various photos of the same painting. No reproduction can substitute for seeing the actual painting. Monet did about 140 paintings of snow, but they represent just a fraction of his work. It’s snowing this morning March 18 and, looking out the window, I see only white, gray and brown with touches of forest green in the grass and pines. But I try to imagine how Monet would have seen it and the answer is that would depend on where he was in his long career.

The Road to Giverny in Winter is from Monet’s mid-career, before the extreme abstraction of his late style, but with the abundance of color characteristic of the fully developed Impressionism. There are several contrasting textures and the blurriness in the foreground indicates an icy wind. Some very dark blues and purples represent tree trunks and limbs, serving to anchor the painting’s composition. If Monet had a unifying color in The Road to Giverney in Winter, I’d guess that it had been blue. There are gray blues, powder blues and green blues. His blue is mostly a soft blue, but it is so well modulated with the pink, the green, the purple, rusty red and yellow.

|

| The detail from the center of The Road to Giverny in winter shows Monet’s array of colors |

The center is yellow, though. That’s the beginning of Giverny, the village he lived in from 1878 until his death in 1923. It’s where he created the ponds and nurtured the lily pads which gave rise to his most famous paintings. He placed this village in the center of the painting and painted its buildings yellow, appropriate because Giverny was a place of warmth where he found his center, his life. Warm yellow ochre meets its match in the yellows of the sky. There, it takes on radiance, brightness and a hint of green. The touch of green in the sky balances a deep forest green along the road on the right.

Color and composition are wonderful, but the brushstrokes are another reason this painting is so successful. Through his textural strokes, he suggests the flow of light at the end of day, the directions of winds and the barrenness of winter trees. Yet the sky is very smooth and we can sense that our shoes or boots will sink if we walk on the ground.

|

| Claude Monet, The Magpie, 1868-1869 |

The Magpie, one of the most popular paintings in Paris’ Musée d’Orsay, is also one of his earliest snow paintings. From this work, we trace how much he changed as his Impressionist style developed. He painted The Magpie in 1868-1869, before the first Impressionist exhibition of 1873. The public was not used to white paintings and it was rejected by the Salon of 1869. The way Monet created the magpie as a focal point in the composition reveals his genius, leading our eye to the bird through contrast and through repeated lines of movement in the fence’s shadows. The brushwork is masterful, as he uses the brush to show light, shadow and what remains of snow on narrow branches of trees.

The Magpie is a masterpiece of Monet’s early style, more Realist than Impressionist. There’s a sharp differentiation between light and shadow, though the shadows are mainly blue and not gray. Dark footprints in the foreground add a bit of mystery, but more than anything make us think of the rawness of nature’s beauty with only a hint of human intervention. He is still using black which may have added just the right amount of contrast. If we could not see the energy of his brushstrokes, a viewer may think the painting’s quality so good that it could be a photograph. The whites are bright enough, though, that you’d almost want to wear sunglasses to look at the painting. The Magpie appears to work its special magic by depicting what may be the day after a night of snow.

|

| Monet, The Street at Argenteuil, Snow Effect, 1874 |

In contrast to the view of snow in sunlight, it’s snowing in The Street at Argenteuil, Snow Effect, painted about 5 years later. The snowflakes are big, perhaps Monet was inspired by Japanese artist Hokusai. The whites are still very bright, but the most of the painting is gray or taupe, with touches of deep green and deep purple to make up the dark colors. There is a feel of something magical to be walking in this snow, even if it is cold. There’s touches of blue in the sky and a forest green where grass or pine needles appear.

|

| Monet, Snow at Argenteuil, 1875. Argenteuil was particularly important to the development of Monet’s Impressionist style. The years 1875-79 included some cold, harsh winters. |

Snow at Argenteuil, 1875, could be the day after a snow. It was painted in the same village but perhaps a year later. Its also a logical progression of style.Value contrast diminishes, but Monet loves to create a sense of depth and he is truly a master of perspective space, as much as the master of reflecting color. Black is almost entirely eliminated but we only have a few strokes of colors in their dark values. The town, nature and people are alive with movement and they go about their business despite the overall chill in the air. The blue in the painting, and the red bricks that been dulled to a pink, let us know it’s cold outside.

By 1880, Monet’s paintings were gradually becoming more and more abstract. He was less concerned with structure, depth and perspective. The paintings become more and more about color, pattern, vibration. In the Floating Ice near Vertheuil, we see tons of blue: deep blues green-blues, purple-blues and powder blue for the sky. Nearly half the painting is a reflection of the water, something he take to full abstraction with his water lily paintings later. It’s not only about the weather and how light effects the color, but Monet was also very concerned with pattern. The brushstrokes look like dabs of paint, just quick impressions.

|

| Monet, Floating Ice Near Vetheuil, 1880 |

As time goes on, even his snow scenes begin to take on more colors. Fortunately, 19th century painters were allowed an expanded palette of colors, and, for the first time, they could buy their paints in tubes. In many paintings, snow and ice become less dominated by white and gray, and appear to be dusted with all the hues of the rainbow. Near Lavacourt and Vetheuil, he did many paintings of the break up of ice on the River Seine. In these paintings, snow and ice combine with water in Monet’s color analysis of the reflections as they hit the water.

|

| The Road to Giverny in Winter is chronologically between the ice series on the Seine and the Grainstacks series |

|

|

|

Monet’s Grainstacks series of about 25 paintings includes at several snow scenes which offer a good comparison if we see them as Monet intended, next to the other paintings in the series. The Art Institute of Chicago’s painting, Grainstacks, Snow Effects, Sunset, 1891 is an example. This painting, an explosion of color on form is viewed in the gallery with at least six other paintings from the series. Shadows are not painted black or gray, but only as cold colors. (Blue, green and purple are cold colors, yellow, orange and red are warm.) Complementary color contrast creates a sensation, with the warmest colors in the upper righthand corner.

|

| Monet, Grainstacks, Snow Effect, Sunset, 1891 |

Monet traveled to Norway in 1895 and painted landscapes in the palest of colors. From Sandviken, Village in the Snow, it’s apparent that Monet’s interest in spatial depth, so apparent in earlier paintings, is gone, and overlapping shapes are the only forms to give definition to space. He used the lightest of pastel tints to differentiate color in paintings flowing with the brightness of snow, or in the whiteness of paint. The reds of barns are very red, yet they are submerged in white. It does seem that snow is everywhere and this is truly a winter wonderland. The edges of the canvas look as if they could dissolve in continuity.

|

| Monet, Sandviken, Norway, Village in the Snow, 1895 |

If snow continually inspired Monet and if he pressed himself to paint it whenever possible, we must see his relationship of snow as being akin to his relationship with painting water. Snow, like water, was a vehicle for him to explore the wonders of refracting light and reflection, to scatter colors as they reflect off of each other while forming unexpected designs and patterns.

About 10 years ago I took a painting class. Using a photo of a snow scene from the Morton Arboretum, my teacher kept encouraging me to see the purple in the landscape. She said that every landscape has an underlying color that unifies it and in this one it’s purple. The snow is purple, the water is purple, the tree trunks are purple, she said, and suggested that I stop interpreting what I knew was there: grays, whites, browns and blacks. She was trying to help me see as the artist sees and to use my eye to see an Impressionist’s vision of the world. There also was a gorgeous sunset in the painting I was doing, but I certainly didn’t paint a glorious rainbow of color effects as Monet did. Check out more of his snow scenes on this website.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments