by Julie Schauer | Aug 24, 2015 | 19th Century Art, Degas, Gustave Caillebotte, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Monet, National Gallery of Art Washington, Paul Durand-Ruel, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Seurat

|

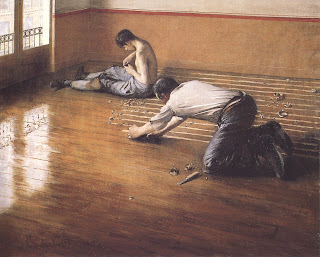

Gustave Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers, 1875 Musée d’Orsay, now on view

at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, |

Right now the National Gallery is having an exhibition of an Impressionist whose reputation has grown over the last 25 years, Gustave Caillebotte. Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye will be on view until October 4.

Caillebotte’s first masterpiece, The Floor Scrapers, was rejected by the Salon in 1875, but accepted into the Impressionist group exhibition the next year. He repaid his dear friends by buying up many of their works and then donating them to the French state after he died. Today many of those paintings belong to Paris’ great early modern museum, Musée d’Orsay.

There are so many reasons The Floor Scrapers is my favorite work by Caillebotte. The composition is extraordinarily well balanced with artful asymmetry on a tilted floor plane. (The invention of photography encouraged artists to look through the viewfinder and frame pictures differently.) There’s also the dignity given to labor, the working man and his beautiful anatomy.

Most it’s incredible to see how Caillebotte painted tactile contrasts on wood in the various stages of sanding, what looks like with or without varnish, and in the light and shadow. Caillebotte painted with more definition and precision than other Impressionists. Yet he illuminates the floor with natural light from the window and we see a wonderful scintillating values, colors and textures. Yellow shines through with touches of blue, but in the distance everything becomes an earthy brown color.

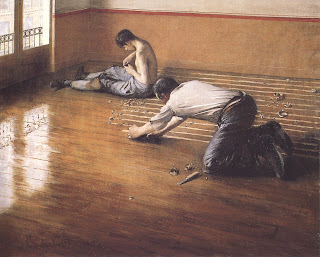

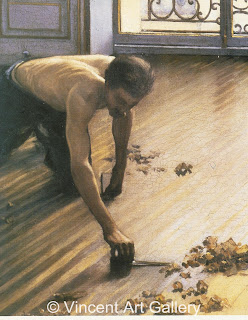

Caillebotte painted another floor scrapers

To understand how good this painting actually is, it’s useful to compare it with another version of floor scrapers that he did. It’s a simpler composition from a different angle, with fantastic lighting effects. Enlarging the photo here will really show off the reflections on the floor. (It isn’t in the National Gallery’s show, but was also part of the 2nd Impressionist exhibition in 1876.)

|

| Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers |

Many of Caillebotte’s other paintings in the exhibition also convey his artful sense of perspective: Le Pont de l’Europe, 1876, for example. He lived at the time that Paris had just experienced a massive rebuilding campaign of boulevards. Paris, A Rainy Day gives an impressive viewpoint of how the new city must have looked to the public, in the eyes of a new bourgeoisie class. Since streets corners were set up in star patterns, the linear perspective goes very deep into multiple vanishing points. A more famous artist, Georges Seurat, borrowed from the composition of Paris: A Rainy Day when he did his iconic painting of Paris on a sunny day, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte.

Other artists of the same time

Monet and Van Gogh are other who shared Caillebotte’s love of deep perspective space. Degas went even further than Caillebotte to exploit the unusual viewpoint. His work can be seen in an important Impressionist exhibition is in Philadelphia, Discovering the Impressionists, until September 13. The exhibit showcases Paul Durand-Ruel, the art dealer who took a gamble and went into great financial risk by buying up Impressionist painters because he believed in them. The exhibit includes Monet’s beautiful Poplars series. However, one of the really important works in the group is by Degas, The Dance Foyer at the Opera on the rue Le Peletier.

|

Edgar Degas, The Dance Foyer at the the Opera on the rue Le Peletier, 1872,

Musée d’Orsay, Paris, now on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art |

Comparing Caillebotte’s Men to Degas’ Dancers

This panoramic ballet scene of dancers offers a wonderful comparison with the Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers. This painting is also asymmetric and appears to look spontaneous, while it is actually exceptionally well-planned. Degas offers more layers of observation: into another room and out the window, through a mirror (?) or another room in the back center. We imagine that the major source of light is a an unseen window to the right. Whites and golds predominate the scene, with touches of blue and orange. Degas’s dancers, though quite strong, may seem delicate next to Caillebotte’s muscular workers.

In truth, Degas’ dancing girls and Caillebotte’s hard-working men are much the same. Their work is a labor of love, as the Impressionists saw it. The same can be said about Caillebotte, Degas, Durand-Ruel and those who left us with a wonderful record of life in Paris in the 1870s. The ballet painting was done in an opera house that destroyed by fire the very next year, probably caused by gaslights.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2024

by Julie Schauer | Dec 4, 2014 | 19th Century Art, Cassatt, Degas, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, National Gallery of Art Washington, Sculpture

|

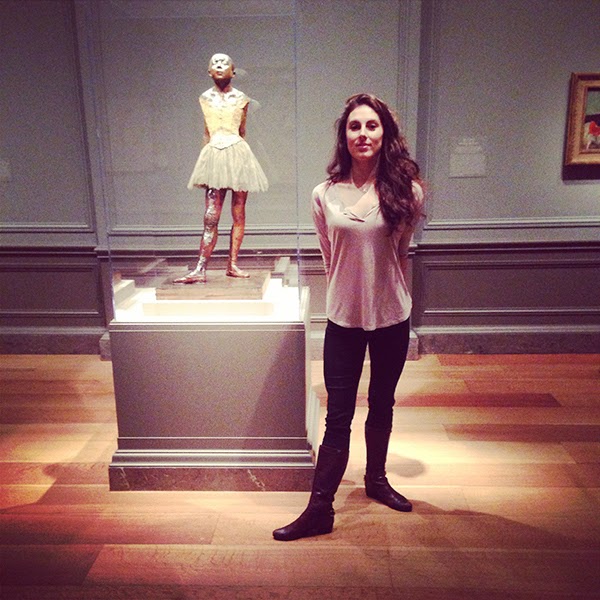

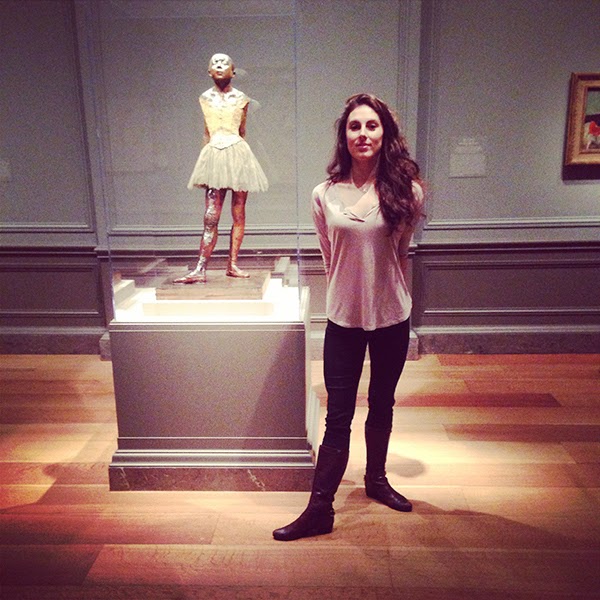

| Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, 1878–1881,pigmented beeswax, clay, metal armature, rope, paintbrushes, human hair, silk and linen ribbon, cotton and silk tutu, linen slippers, on wooden baseoverall without base: 98.9 x 34.7 x 35.2 cm (38 15/16 x 13 11/16 x 13 7/8 in.) weight: 49 lb. (22.226 kg) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

|

It was a joy to see the Kennedy Center’s world-premiere production, The Little Dancer, which closed on November 30th. Tiler Peck, principle of the New York City Ballet had the lead as 14-year-old Marie van Goethem, the ballerina who posed for Degas’ famous statue, Little Dancer. Although Peck is definitely far more mature than Degas’ model was, she certainly was a good choice for the role. Boyd Gaines, as Degas, really does not look like him but I guess it doesn’t matter. Some of the settings and compositions are the same as you will see in his paintings. (My blog about Degas’s paintings of dancers)

|

The music is delightful, and most of the story is fairly credible, so I do hope the musical will go to more venues. The Kennedy Center audiences loved it. The musical fits in with what I’ve been writing about, Degas and Cassatt and the relationships between artists. The story opens in 1917 with a visit to Degas’ household after his death. Mary Cassatt is there, wishing to turn the ballerina away, but she came back to see the sculpture he did of her many years earlier. It’s fairly funny as it refers to the yellow coat with a fur collar that was annoying to Marie.

|

| Tiler Peck in front of the National Gallery of Art’s Little Dancer Aged Fourteen , from Tiler Talks Blog, October 15, 2014 |

The story is truthful in that portrayed some of the challenges in the lives of the dancers who were working class girls. Marie’s mother was a laundress, and I’m guessing she posed for Degas, too. Laundresses — like dancers and race horses — were part of Degas’ continuous subject matter, as he studied the movements of muscles and limbs at work and in stress. (While we think of dancers and race horses expressing consummate grace, we don’t think of laundresses that way.) In the play, Marie was put into a competition with snooty, upper class girl who had a stage mother, a story for a Disney movie or a story which would be more truthful today. Wealthy girls were not so likely to be ballerinas in the 19th century, as their parents wouldn’t have subjected them to gawking men. Class differences, as a major theme of the play, are historically correct for the time. Other details of biography, Degas’ grumpy outer shell that hid his softness, his sensitivity to strong light and fear of going blind were woven into the tale. Of course, the close companionship and artistic relationship with Mary Cassatt, especially during the time Marie would have posed, were very true.

|

| Tiler Peck as Marie, the Little Dancer, in the Kennedy Center Musical of that name |

The musical, too, has flashbacks to old the older and younger Marie. Rebecca Luker, an experienced Broadway star who plays the older Marie, has a powerful voice. The musical is similar to a recent genre of books which use a work of art to create a historical fiction. Like Girl with a Pearl Earring, Tracy Chevalier’s book about Jan Vermeer and his famous subject, much of the details are imagined.

For the importance of the statue artistically, the National Gallery of Art will have Little Dancer Aged Fourteen on display in an exhibition with other sketches, paintings and sculpture until January 11, 2015. I think the importance of Degas’ wax sculptures as comparable the importance of his sketches. Waxes to bronzes are like drawings are to paintings, although not necessarily the case here. It helped him realize his vision for his paintings.

|

Fourth Position Front, on the Left Leg, c. 1885/1890 pigmented beeswax, metal armature, cork, on wooden base

overall without base: 60.3 x 37.8 x 34.1 cm (23 3/4 x 14 7/8 x 13 7/16 in.)

height (of figure): 56.8 cm (22 3/8 in.)

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon |

Degas built the statue in wax over an armature, and he did it in an additive process. In the play, it is called a “characterizing portrait.” and As such, it was quite innovative. Details are not the important part as much as the essence the characterization. The play opens with a famous by Degas: “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.” What Degas did so brilliantly make us see the essence of the practice, the work, the attitude and the dedication which made the ballet become what it became. Most of his paintings are of rehearsals rather than performances. Seeing his work makes our lives richer, and seeing “Little Dancer” enriches us. Even the 6-year old boys near me were entranced by it.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Oct 1, 2014 | 19th Century Art, Cassatt, Degas, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Portraiture, Women Artists

|

| Mary Cassatt, La Loge, 1878-79 |

Mary Cassatt was several years younger than Edgar Degas, but when he saw her work he exclaimed, “Here’s someone who sees as I do.” Currently, the National Gallery is showing Cassatt side by side with Degas, comparing how they two worked together and shared. Both are remarkable portrait artists.

Like Manet and Morisot, their relationship was especially helpful for each of them reach the fullness of artistic vision. They spent about ten years working closing together. As their artistic visions changed, they grew in different directions. They share same daring sense of composition. Both are excellent portrait artists. I just finished reading Impressionist Quartet, by Jeffrey Meyers. It’s the story of Manet, Morisot, Degas and Cassatt: their biographies, their art and their interdependence.

|

| Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt |

Degas and Manet were good friends, too, and had a friendly competition. They had much in common, having been born in Paris and coming from well-to-do backgrounds. Both had a strong affinity for Realism, but Degas was the greater draftsman, and probably the greatest draftsman of the late 19th century. (Read my blog explaining Degas’s dancers) Cassatt and Morisot also were friends, as the two women who were fixtures of the Impressionist group. They were very close to their families, and their subjects were similar. Their personalities were quite different. Berthe Morisot was refined and full of self doubt, while Mary Cassatt was bold and confident. Cassatt did not have Morisot’s elegance or her beauty.

Her confidence shines in all of Degas’ portraits. She was not too pleased with the portrait at right, but Degas often did get into the character of his subjects. Degas painted her leaning forward and bending over, and holding some cards. He put her in a pose used in at least two other paintings, but I’m not certain what he meant by this position. The orange and brown earth tones, and the oblique, sloping asymmetric composition are very common in Degas’ paintings.

Degas may have been somewhat shy, but caustic, biting and moody. By all accounts, it appears that Cassatt made him a happier person. Degas was the one who invited her to join the Impressionist group in 1877, three years after it had formed.. They worked together to gain skills in printmaking. In addition, to their common artistic goals and objectives, both had fathers who were prominent bankers. Mary Cassatt was an American from Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, while Degas had relatives from his mother’s family who lived in New Orleans. Some of his father’s family had moved to Naples, Italy, and had married into the aristocracy there.

No on seems to know if they were lovers. Both artists were very independent, remained single their entire lives. Neither was the type who really wanted to be married. However, each of them had proposed to others when they were very young, and before they knew each other. Writers don’t spend a lot of time speculating about their love lives, still an unknown question. Most art historians believe Degas sublimated his sexual energies fairly well while exploring the young girls and teens who were ballet dancers.

|

| Degas, Henri De Gas and His Niece Lucie, 1876 |

I have always loved this painting of Henri De Gas and his niece Lucie, from the Art Institute of Chicago. It seems a very sympathetic portrait of his uncle and cousin, both of whom have kindly faces. Sometimes it’s been explained that the chair as a vertical line showing the separateness of the relationship. I see it differently. The composition has a large diagonal, and an arc brings are eye from the upper right side to the lower left corner. A continuous compositional line from their heads down to the edge of his hand and the newspaper pulls the older man and young girl together. There heads are nearly at the same angle, single expressing their togetherness. The uncle looks like such a kindly man, and both look at us the viewers.

|

| Marry Cassatt, Portrait of Alexander Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso Cassstt |

Mary Cassatt also shows an even stronger family bond in the Portrait of Alexander Cassatt and His Son, Robert Kelso Cassatt, her brother and nephew. Her brother ultimately rose to be President of the Pennsylvania Railroad and may have been somewhat of a robber baron. You would never see his harshness in his sister’s portrayal. He seems like the ultimate warm, affectionate father. The two faces are placed so closely together, and they’re similar. Degas and Cassatt often portrayed individuals in relation to each other to show their great affection for each other, so differently from the way Manet did. In most of his group portraits Manet makes us keenly aware that each individual is a unique soul. He emphasizes differences and oppositions,

One the best of Mary Cassatt’s portraits is the Young Girl in a blue armchair.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Oct 6, 2011 | 19th Century Art, Art Appreciation: Visual Analysis, Degas, Exhibition Reviews, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, The Phillips Collection

Two Dancers at the Barre, early 1880s−c. 1900, Oil on canvas, 51 1/4 x 38 1/2 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1944. This painting is the centerpiece of the current exhibition.

Point….Flex…..Relevé—–these themes of ballet dancing were the obsession of Edgar Degas, an artist associated with Impressionism but known for his paintings and pastels of dancers. Washington’s Phillips Collection recently put their large painting, Dancers at the Barre, under their conservator’s care. In the process, they discovered wonderful color and took a deeper look into the process of this artist. The exhibition Degas’ Dancers at the Barre: Point and Counterpoint transports the viewer into Degas’ mind and back into the opulent Garnier Opera House which opened in Paris in 1875.

Most of the paintings, drawings and studies in the exhibition feature women, mainly ballerinas. After viewing the show, I once again get the feeling that Degas is the foremost among artists in his understanding of the strength of the female body, just as Michelangelo leads all artists in the understanding of the male bodies. However, unlike Michelangelo, Degas did not demonstrate knowledge of musculature or make his figures sensual. At times he appears to negate the underlying anatomy and distort in order to show the body’s expressive possibilities.

Ballet Rehearsal, c. 1885–91. Oil on canvas, 18 7/8 x 34 5/8 in. Yale University Art Gallery. Gift of Duncan Phillips, B.A., 1908 The composition is asymmetric, typical of Edgar Degas.

Degas’s compositions are about contrast: left and right, point and counterpoint, up and down, orange and blue-green, line and shape, solid forms but with diaphanous clothes, stability and movement. He portrays movement with color and with spontaneous, oblique compositions, allying him with the Impressionists. He exhibited with them from 1873-1886. Arguably, Degas was the greatest of all draftsman during the 2nd half of the 19th century, a time of tremendous artistic creativity.

Degas’s studies of dancers reveal his desire to understand and express the outward effects of stretch and stress, not inner musculature. At this time, ballet was not the idealized performance art we imagine. Instead young girls worked long hours under difficult conditions, with much strain on their youthful physiques. Under Degas’ interpretation, we witness the precision and tour de force of their labors. He drew and painted the rehearsals more frequently than actual performances. In Degas’s early paintings, the viewers admire the dancers’ poise and balance, as they move into difficult positions. In later works, such as the signature piece of the exhibition, we see much contortion and distortion, somewhat like a Cirque du Soleil performance. Through Degas’s drawings, paintings and pastels, we do not necessarily appreciate the body’s outward beauty, but we understand its possibilities, flexibility and the strength of human effort. The bodies’ movements are gestural and evoke strong feelings.

Dancer Adjusting her Shoe,1885, Pastel on paper, 19 x 24 in. Collection of The Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, Tennessee; Bequest of Mr. and Mrs. Hugo N. Dixon, 1975.6. Drawings repeat poses in his paintings and often show changes of the artist’s mind.

Degas is unique amongst the Impressionists in the strength of his line. Outlines at times contrast with the soft tutus of transparent colors. But his colors are sometimes brilliant, particularly oranges and blue-green. There are also vivid bows of pink, yellow, orange and red. He is superb at using color contrast to create light and shadow. Degas painted mainly indoors, but he used natural light from windows to sparkle on his dancers.

He normally works with off-center compositions, an effective foil to the dancers in their shoes. His asymmetry is like the fragile balance of the ballerinas on the tip of their toes: it can be a precarious balance. The art of the ballerina is to remain strong and poised in difficult positions, and Degas balanced his asymmetric compositions artfully, which was equally a challenge.

In a nearby gallery are the works of other artists, such as Manet‘s Spanish Ballet. Sculpture helped Degas refine his vision and the exhibition includes 3 bronze-cast sculptures. Like any great artist, he worked on the same themes over and over, same pose with slight differences. Several late works are pastels, a ideal medium for his methods. The Phillips’ exhibition also runs a filmed performance of Swan Lake.Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas, Two Dancers Resting, c. 1890–95, Charcoal on paper, 22 3/4 x 16 3/8 in. Private Collection.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments