by Julie Schauer | Feb 10, 2016 | 20th Century Art, Constantin Brancusi, Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi, Louise Bourgeois, Sculpture, Surrealism

“Contemporary and ancient art are like oil and water, seemingly opposite poles….now I have found the two melding ineffably into one, more like water and air.” Hiroshi Sugimoto, Japanese artist

|

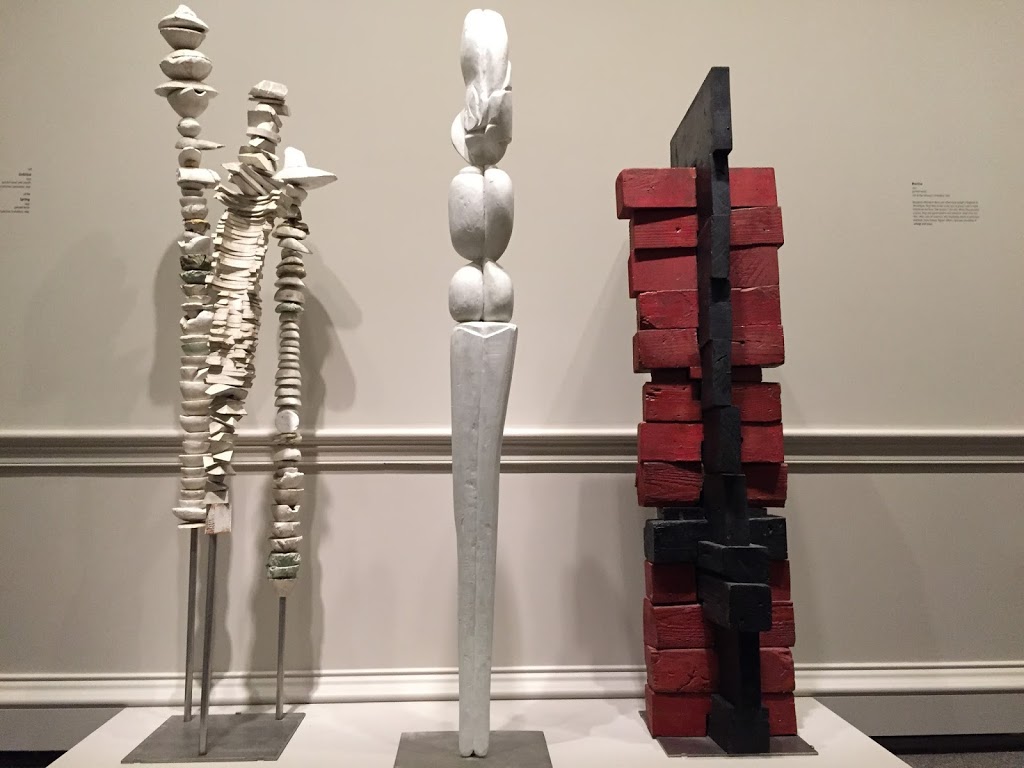

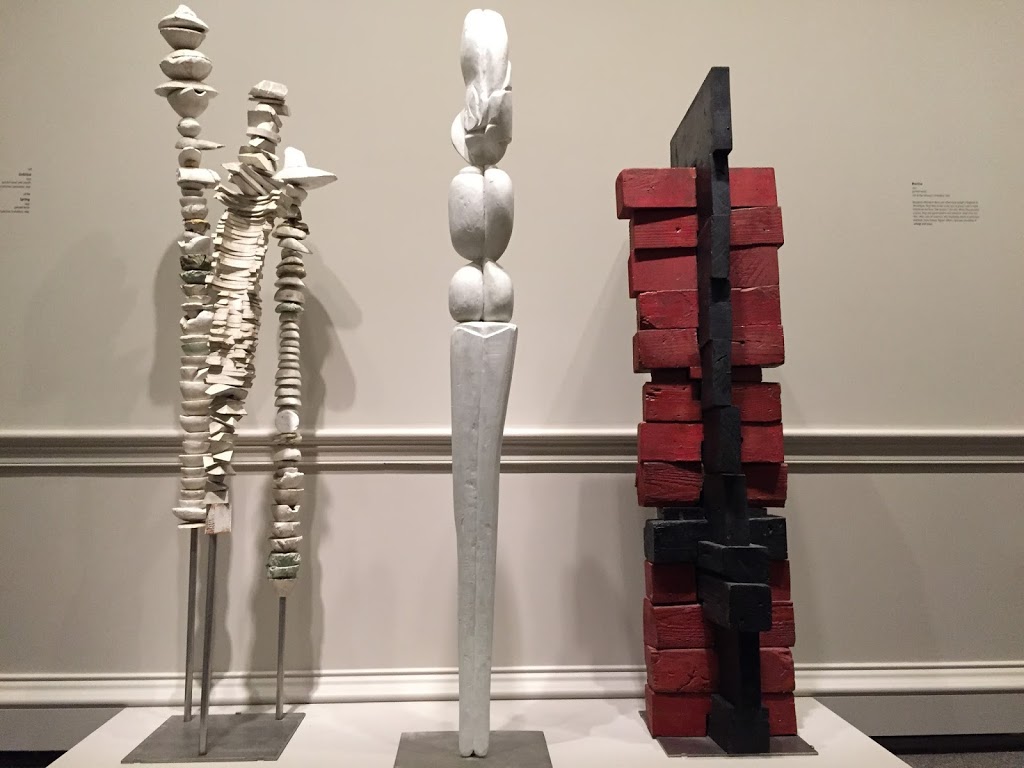

| Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1952, Spring, 1949 and Mortise, 1950 National Gallery of Art |

|

|

Two separate exhibitions in Washington at the moment illustrate the commonality of modern art and prehistoric — especially in sculpture. The me, that theme resonates with two sculptors who lived through most of the 20th century, Louise bourgeois and Isamu Noguchi. The National Gallery has a two-room exhibition Louise Bourgeois:No Exit, and Noguchi (hopefully in another blog)‘s works are part of the Hirshhorn’s exhibition, Marvelous Objects: Surrealist Sculpture from Paris to New York.

|

Constantin Brancusi, Endless Column,1937

|

|

|

Three sculptures by Bourgeois in the National Gallery are what she called personages. As a whole they’re not unlike the archetypal images of Henry Moore or Constantin Brancusi. Among these three works are a group of three piles of stones resting on stilts. It’s one of the Bourgeois sculptures that

|

Barbara Hepworth, Figure in Landscape,cast 1965

|

appears simple and somewhat primitive. Untitled is above on the left. The stones stand tall and top heavy; they seem to be wearing big hats. I’m reminded of the precarious state of human existence. I am also thinking of the top-heavy candidates in the recent Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary, weak on bottom and they may fall. Aesthetically these works form a link to Brancusi’s birds on pedestals and the Endless Column, Targu Jui, Romania, part of a memorial for fallen soldiers in World War I.

The sculpture of Spring center above is reminiscent of a woman, or of the ancient Venus figures, which date to the Paleolithic era, around 20,000 BCE. It can be compared the the elongated marble burial figures from prehistoric, Cycladic Greece as well.

|

| “Venus” figures from Dolni Vestinici, Willendorf, Austria and Lespuge, France |

|

|

|

A version of Alberto Giacometti’s bronze Spoon Woman from the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas is in the surrealist exhibition (Example below from Art Institute of Chicago). Giacometti made this archetypal image in 1926/27, but the bronze was cast in 1954. Henry Moore’s Interior and Exterior Forms, is a theme he did over and over, is an archetype of the mother and child.

|

| Giacometti, Spoon Woman, 1926/27, cast |

1954 |

In 1967, the Museum Ludwig, founded by chocolate manufacturers in Cologne, Germany, asked for one of her sculptures to be replicated in a single large piece of chocolate. She chose Germinal, its name suggestive of germination and new beginnings. (Germinal is also the name of Emile Zola’s famous French novel of 19th century coal minors. I wouldn’t put it past her to be referring to the story, but don’t have an idea as to how and why)

|

| Germinal, 1967, promised gift of Dian Woodner, copyright |

|

|

Bourgeois, who died in 2010, lived to be 98 years. She continually worked and invented anew. In time, I think she will be considered a giant among the sculptors of the 20th century, on par with Moore, Brancusi and Calder. Her art was more varied than the others and she defied categorization and/or predictability. However, certain themes seemed to carry her for long periods of time, such as the personages of her early to middle period and the cells she did late in her life. She worked both vary large and very small and with an infinite variety of materials including fiber. She grew up in a family which worked in the tapestry business, primarily repairing antique tapestries. To her, making art was making reparations making peace with the past. Some wish to put her in the category of Surrealism, but she calls herself an Existentialist, in the philosophical realm of Jean-Paul Sartre. Looking at some of the drawings in the National Gallery and how she explained it does give a clue into the existential thoughts and feelings.

|

| Spider, 2003 (not in exhibition) |

One of Bourgeois’s best-known themes was the spider, having done several monumental statues in public places. The spider stands for the protective mother, and her version of the archetype, as it also alludes to the weaving activity in her family. It is large and embracing but can also have a dark side. I like best the spiders that combine the metal sculpture with the delicate tapestry figures. The delicacy and litheness of her spider people remind me of the wonderful organic acrobat sculptures from ancient Crete.

|

| Bull-leaping acrobat, ivory, from Palace at Knossos, Crete, c. 1500 BCE |

Bourgeois deals with metaphors. She calls sculpture the architecture of memory. She is poetic, but she’s also quite humorous. She also made a sculpture series of giant eyes. She describes eyes mirrors reflecting various realities. I’m reminded that in ancient times, the eyes were the mirrors of a person’s soul. As different as her works may be, she portrays a consistent voice and aesthetic throughout her career.

|

| Eye Bench, 1996-97, Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle |

When I went to the Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle back in 2010, a friend of mine from California and I came upon her Eye Benches. We sat down and enjoyed it. She designed three different sets of eye benches made of granite. In the end, it seems Bourgeois used her art to make sense of her very complicated world and our experience of that world. Sometimes she seems to laugh at it all, so this experience calls for a good laugh and relaxation.

|

| Louise Bourgeois, Eye Bench, Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle. |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Dec 4, 2014 | 19th Century Art, Cassatt, Degas, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, National Gallery of Art Washington, Sculpture

|

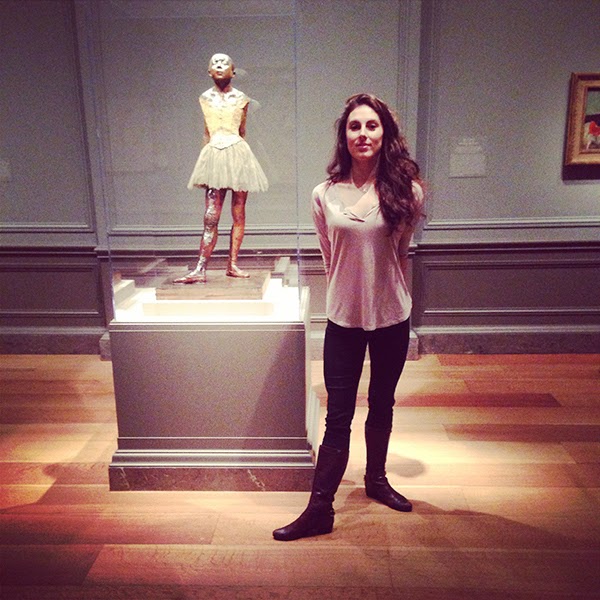

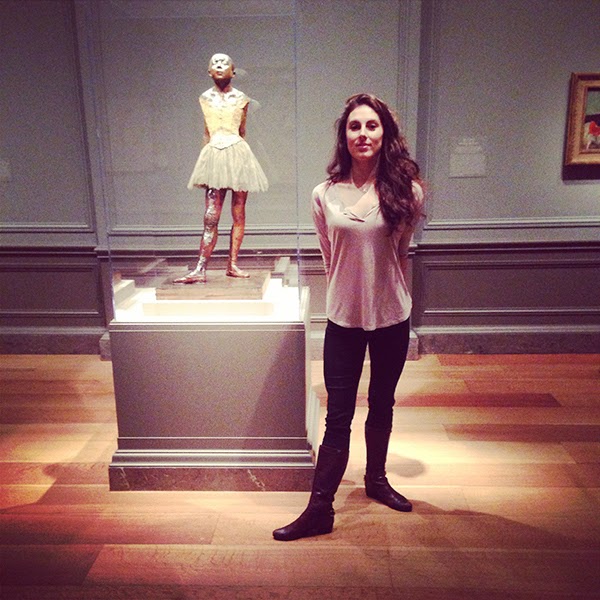

| Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, 1878–1881,pigmented beeswax, clay, metal armature, rope, paintbrushes, human hair, silk and linen ribbon, cotton and silk tutu, linen slippers, on wooden baseoverall without base: 98.9 x 34.7 x 35.2 cm (38 15/16 x 13 11/16 x 13 7/8 in.) weight: 49 lb. (22.226 kg) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

|

It was a joy to see the Kennedy Center’s world-premiere production, The Little Dancer, which closed on November 30th. Tiler Peck, principle of the New York City Ballet had the lead as 14-year-old Marie van Goethem, the ballerina who posed for Degas’ famous statue, Little Dancer. Although Peck is definitely far more mature than Degas’ model was, she certainly was a good choice for the role. Boyd Gaines, as Degas, really does not look like him but I guess it doesn’t matter. Some of the settings and compositions are the same as you will see in his paintings. (My blog about Degas’s paintings of dancers)

|

The music is delightful, and most of the story is fairly credible, so I do hope the musical will go to more venues. The Kennedy Center audiences loved it. The musical fits in with what I’ve been writing about, Degas and Cassatt and the relationships between artists. The story opens in 1917 with a visit to Degas’ household after his death. Mary Cassatt is there, wishing to turn the ballerina away, but she came back to see the sculpture he did of her many years earlier. It’s fairly funny as it refers to the yellow coat with a fur collar that was annoying to Marie.

|

| Tiler Peck in front of the National Gallery of Art’s Little Dancer Aged Fourteen , from Tiler Talks Blog, October 15, 2014 |

The story is truthful in that portrayed some of the challenges in the lives of the dancers who were working class girls. Marie’s mother was a laundress, and I’m guessing she posed for Degas, too. Laundresses — like dancers and race horses — were part of Degas’ continuous subject matter, as he studied the movements of muscles and limbs at work and in stress. (While we think of dancers and race horses expressing consummate grace, we don’t think of laundresses that way.) In the play, Marie was put into a competition with snooty, upper class girl who had a stage mother, a story for a Disney movie or a story which would be more truthful today. Wealthy girls were not so likely to be ballerinas in the 19th century, as their parents wouldn’t have subjected them to gawking men. Class differences, as a major theme of the play, are historically correct for the time. Other details of biography, Degas’ grumpy outer shell that hid his softness, his sensitivity to strong light and fear of going blind were woven into the tale. Of course, the close companionship and artistic relationship with Mary Cassatt, especially during the time Marie would have posed, were very true.

|

| Tiler Peck as Marie, the Little Dancer, in the Kennedy Center Musical of that name |

The musical, too, has flashbacks to old the older and younger Marie. Rebecca Luker, an experienced Broadway star who plays the older Marie, has a powerful voice. The musical is similar to a recent genre of books which use a work of art to create a historical fiction. Like Girl with a Pearl Earring, Tracy Chevalier’s book about Jan Vermeer and his famous subject, much of the details are imagined.

For the importance of the statue artistically, the National Gallery of Art will have Little Dancer Aged Fourteen on display in an exhibition with other sketches, paintings and sculpture until January 11, 2015. I think the importance of Degas’ wax sculptures as comparable the importance of his sketches. Waxes to bronzes are like drawings are to paintings, although not necessarily the case here. It helped him realize his vision for his paintings.

|

Fourth Position Front, on the Left Leg, c. 1885/1890 pigmented beeswax, metal armature, cork, on wooden base

overall without base: 60.3 x 37.8 x 34.1 cm (23 3/4 x 14 7/8 x 13 7/16 in.)

height (of figure): 56.8 cm (22 3/8 in.)

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon |

Degas built the statue in wax over an armature, and he did it in an additive process. In the play, it is called a “characterizing portrait.” and As such, it was quite innovative. Details are not the important part as much as the essence the characterization. The play opens with a famous by Degas: “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.” What Degas did so brilliantly make us see the essence of the practice, the work, the attitude and the dedication which made the ballet become what it became. Most of his paintings are of rehearsals rather than performances. Seeing his work makes our lives richer, and seeing “Little Dancer” enriches us. Even the 6-year old boys near me were entranced by it.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Jul 26, 2013 | Contemporary Art, Eco-Art, Environmental Art, Greater Reston Arts Center, Local Artists and Community Shows, Painting Techniques, Sculpture

|

| William Alburger, Forest, 2013, 65″ x 108″ x 9″ rescued spalted birch, in an solo exhibition at GRACE |

Eco-friendly art is meeting the world of high art, if we’re to take a cue from what’s showing at local art centers and galleries. It can be stated that the earliest environmental art started with the artists’ visions and applied those visions to the environment, with little interest in sustainability.

Quite the opposite trend is developing now. Several emerging artists, the “environmental artists” of the 21

st century put nature in the center–not the artist or the idea. Nature is the subject and the artist is nature’s follower. The following artists’ creations are about the land and earth; other artists interested in the environment have been more concerned with a world under

the sea.

|

William Alburger, Non-traditional Backwards

One-Door, 2012, 27″ x. 13.5″ x 5.25

reclaimed Pennsylvania barn wood, specialty

glass and fabric |

William Alburger lives in rural Pennsylvania, where he picks up scraps of wood from fallen trees and mixes them with discarded barn doors. He is a passionate conservationist with an addiction to collecting what otherwise would be burned, decayed or discarded in landfills. Largely self-taught, Alburger formerly worked as a painting contractor. His art is both pictorial and practical. Some sculptures almost look like two-dimensional works, while others function as shelves or furniture. Hidden doors, cubbyholes and cabinets create surprises, making the natural world his starting point for expression. Intrusions of man-made items are minor. The knots, whirls, colors and textures of wood speak for themselves, revealing rustic beauty.

|

William Alburger, Synapse, 2013,

65″ x 23″ x 5.25″ rescued spalted

poplar and Pennsylvania barn wood |

Currently the Greater Reston Area Arts Center (GRACE) is hosting a solo exhibition of Alburger’s works. In Synapse, Alburger cut into the interesting grain and patterns of fallen poplar. He framed top and bottom with old barn wood and reconfigured the form to suggest the space where two forms meet and form connection. Allburger finds what is already there in nature, but, through presentation, teaches us how to see it in a new way. Otherwise, we might not notice what nature can evoke and teach us.

|

Pam Rogers, Tertiary Education, 2012, handmade

soil, mineral and plant pigments, ink, watercolor

and graphite on paper. Courtesy Greater

Reston Area Art Association |

Dedication to the natural world is second nature to Pam Rogers, whose day job is as an illustrator in the Natural History Museum of the Smithsonian Institution. “I’m inclined to see environment as shaping all of us,” Rogers explains, noting the importance of where we come from, and how our natural surroundings mark our stories and connections. While drawing natural specimens, she sees as much beauty in decay is as in birth, growth and development. We’re reminded that everything that comes alive, by nature or made by man, will turn to dust. Rogers’ drawings combine plants, animals and occasional pieces of hardware. Some of the pigments spring from nature, the red soil of North Georgia and plant pigments.

As in Alburger’s Synapse, above, Rogers seeks to form connections between man and the environment. She inserts nails and other links into the drawings from nature for this purpose, as in Stolen Mythology, below. At the moment, Pam Rogers’ art is in the show, {Agri Interior} in the Wyatt Gallery at the Arlington Arts Center. One of her paintings is now in a group exhibition, Strictly Painting, at McLean Project for the Arts.

|

Pam Rogers, Stolen Mythology, 2009 mixed media

|

Rogers mixes traditional art techniques with abstraction, natural with man-made, sticks and strings, and does both delicate two-dimensional works and vigorous three-dimensional art. Her sculptures and installations explore some of the same themes. At the end of last year, she had an exhibition at GRACE called Cairns. Cairns refer to a Gaelic term to describe a man-made pile of stones that function as markers. Her work, whether two-dimensional or three-dimensional, is also about the markers signifying the connections in her journey.

|

| Pam Rogers, SCAD Installation (detail), plants, wire, metal fabric, 2009 |

“There are landmarks and guides that permeate my continuing journey and my exploration of the relationship between people, plants and place. I continually try to weave the strings of agriculture, myth and magic, healing and hurting.” Several of her paintings have titles referring to myths, including Stolen Mythology, above, and another one called Potomac Myths. Originally from Colorado, Rogers also lived in Massachusetts and studied in Savannah for her Masters in Fine Art. It’s not surprising that, in college, she had a double major in Anthropology and Art History.

|

Henrique Oliveira, Bololô, Wood, hardware, pigment

Site-specific installation, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution

Photograph by Franko Khoury, National Museum of African Art |

Artists cite the spiritual and mythic connection we have to environment. As a student, Brazilian artist Henrique Oliveira noted the beauty of wood fences which screened construction sites in São Paolo. Observing these strips being taken down, he collected them and re-used the weathered, deteriorating sheets of woods for some of his most interesting sculpture. Oliveira was asked to do an installation in dialogue with Sandile Zulu for the Museum of African Art in Washington, DC. His project, Bololô, refers to a Brazilian term for life’s twists and tangles, bololô. The weathered strips can act like strokes of the paint brush, with organic and painterly expression, reaching from ceiling to wall and around a pole but usually not touching the ground. Oliveira’s installation is a reflection of the difficulty in staying grounded in life, in this tangle of confusion.

|

Danielle Riede, Tropical Ring, 2012, temporary installation in the Museum of Merida, Mexico

photo courtesy of artist |

|

|

Environmental concerns played a part in the collaboration of Colombian artist Alberto Baraya and Danielle Riede, at the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art, shown in 2011. Expedition Bogotá-Indianapolis was “an examination of the aesthetics of place and its plants” in central Indiana. For two years, the artists collected artificial plants from second-hand stores, yard sales and neighborhoods in around Indianapolis. Last year Riede did an installation for the City Museum of Merida, Mexico, Tropical Ring. It’s made of artificial plants garnered from second-hand crafts in from Indiana and Mexico. The plants were cut and reconfigured to evoke the pattern of an ecosystem, indoors. Currently, the artist is looking for a community partner to participate in Sustainable Growths, an art installation of crafts and other re-used objects destined for abandoned homes in Indianapolis.

|

Danielle Riede, My Favorite Colors, 2006, photo courtesy

http://www.jardin-eco-culture.com/

|

|

|

|

Originally, Riede’s primary medium was discarded paint, which she gathered from the unused waste of other artists or the pealing pigments of dilapidated structures. My Favorite Colors, right, follows several paths of recycled paint along the wall of the Regional Museum of Contemporary art Serignan, France. Beauty comes from the color, light, pattern, and even from the shadows cast on walls to deliberate effect. The memory landscape is uniquely described in the eco-jardin-culture website. The installation is permanent, although much of what we consider environmental art is temporary.

|

Sustainable Growths: Painting with Recycled Materials is Riede’s

project to bring meaning to abandoned homes in Indianapolis. Artist’s photo |

Fallen trees, branches and other wastes of nature are tools of drawing to artist R L Croft. Some artists feel they have no choice but to re-use and re-claim discarded goods or fallen debris, as many folk artists and untrained artists have always been doing. The need to draw or create is innate and a constant in one’s identity as an artist, but it’s not easy to get commissions, jobs or sell art. Art materials are very expensive, so there is a practical objective to using environmental objects which do not need to be stored.

|

| R L Croft, Portal, 2011, Oregon Inlet, North Carolina |

To Croft, using the environment is a means of drawing, but on a very large scale. His outdoor, impromptu drawings-in-the-wild are images grounded in his style of painting and sculpture. Croft has made a number of sculptures called “portals” and/or “fences,” most of which have been carried away by rising tides or decay. He makes these assemblages out of debris found along the beaches, particularly those of the Outer Banks, in North Carolina. Portal at Oregon Inlet, NC, left, was constructed of found lumber, nails, driftwood, plastic, rope, bottles, netting, etc.

Environmentalism is not the primary content of his art. Croft says: “Making art for the purpose of being an environmentalist doesn’t interest me. Making art whose process is environmentally friendly does interest me.” He works in rivers, woods and on beaches. In the aftermath of one natural disaster, Hurricane Irene, he brought meaning to the incident–both personal and anthropological.

.jpg) |

R.L. Croft, Shipwreck Irene, in Rocky Mount, N.C. Built in October, 2012, it’s still there but

less recognizable as a ship form. The location is in Battle Park

off of Falls Road near the Route 64 overpass. Photo courtesy of artist.

|

Croft made Shipwreck Irene in Rocky Mountain, NC, when the Maria V. Howard Art Center held a sculpture competition and allowed him the use of fallen debris after Hurricane Irene, which left as much physical devastation as his sculptures allude to metaphorically. The shipwreck is a very old icon in the history of art, usually associated with 17th century Dutch seascapes. But to Croft, who in childhood found healing in the Outer Banks after the death of his mother, the meaning is deep. The area known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic” fed his early sense of adventure and aesthetic appreciation for texture, decay and the abrasive effects of wind, sand and water.

Hurricane Irene “is much like the resilient community frequently raked over by severe hurricanes, yet plunging forward. The current art center is world class and it is the replacement for an earlier one destroyed when still new. ” Croft said. Shipwreck Irene is still there, but decay renders it increasingly unrecognizable as a ship form. The temporary aspect is expected. “People of the region know grit and impermanence,” the artist explained. “I’m told that Shipwreck Irene became a habitat for small animals and small birds but that is a happy accident.”

|

| R L Croft, Sower, 2013, 22 x 14 courtesy artist |

|

Croft has also said: “Nothing can be taken for granted. Constant change proves to be the only reliable point of reference. Equilibrium being as fleeting as life itself, one fuses an array of thought fragments retrieved from memories into a drawing of graphite, metal or wood. By doing so, the artist builds a fragile mental world of metaphor that lends meaning to his largely unnoticed visit among the general population.” Croft did an installation in the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, a drawing in the wild entitled Sower, in homage to Van Gogh He worked in wattle to make a large drawing that, in a metaphorical, abstracted way, resembles a striding farmer sowing his seed. The farmer is the winged maple seed and it references Vincent’s wonderful ink line drawings.

Nature has been the subject of art by definition and a curiosity about the natural world has defined a majority of artists since the Renaissance. The first wave of Environmental Artists applied their vision to the environment by directly making changes to the environment–permanent (Robert Smithson, James Turrell) or temporary (Christo and Jeanne-Claude) Turrell ,whose most famous work is the Roden Crator in Arizona, is the subject of a major

retrospective now in New York, at the Guggenheim.

It is one thing for art to alter the environment, as the earliest environmental artists did. It is another thing to make art to call attention to the problems of waste and depletion of the earth’s resources. Yet, it’s an even stronger statement when professional artists exclusively make art that re-uses discarded items and turns them into art. Environmental Art today addresses waste reduction and stands up against the problems caused by environmental damage to our rapidly changing world. Designers are getting into this process, as explained in the previous blog. For example, Nani Marquina and Ariadna Miguel design and sell a rug made of discarded bicycle tubes, Bicicleta.

In the future, I hope to blog on how artists address sustainable agriculture. Currently, the main exhibition at Arlington Arts Center, Green Acres: Artists Farming Fields, Greenhouses and Abandoned Lots.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Nov 28, 2012 | Architecture, Christianity and the Church, Mosaics, Sculpture, Sicily, The Middle Ages

|

Sicily was controlled or settled at various times by Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Saracens,

Normans and Spaniards. This view is Monreale, in the north, east of Palermo. |

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

|

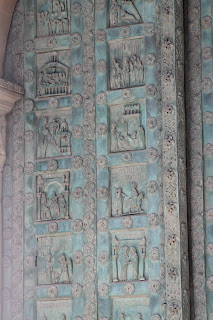

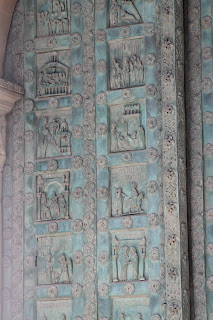

Bonnano of Pisa cast the bronze doors

in 1185 |

A Norman ruler, William II (1154-89), built Monreale Cathedral between 1174 and 1185. When the Roman Empire first became Christian, Sicily reflected the ethnic Greeks who lived on the island. In the 8th century, Saracens conquered Sicily and held it for two centuries, although a majority of residents were Christians of the Byzantine tradition. William the Conqueror’s brother Roger took over the island in 1085, but allowed the other groups to live peacefully and practice their religion. Normans, Lombards and other “Franks” also settled on the island, but the Norman rule between the late 11th and late 13th centuries was quite tolerant. By the 13th century, most residents adopted the Roman Catholic faith. Germans, Angevins and finally, the Spanish took control of the island.

|

This pair of figural capitals in the cloister could be a biblical

story such as Daniel in the Lion’s Den or even a pagan tale |

Monreale Cathedral was built on a basilican plan in the Romanesque style that dominated Western Europe in the 12th century, although the Gothic style had already taken hold in Paris at the time of this building. It is based on the longitudinal cross plan with a rounded east end. Two towers flank the facade. (This Cathedral ranks right up with Chartres and Notre-Dame of Paris, as one of the world’s most beautiful churches.)

|

Capitals feature men, beasts and beautiful

acanthus leaf designs |

In the artistic and decorative details, there is great richness. The portal has one of the few remaining sets of bronze doors from the Romanesque period. These doors were designed and cast by a Tuscan artist, Bonanno da Pisa. A cloister, similar to the cloisters of all abbey churches has a beautiful courtyard with figural capitals. Its pointed arches betray Islamic influence. The sculptors who carved the capitals are thought to have come from Provence in southern France, perhaps because of similarity in style to abbey churches near Arles and Nîmes, places with a strong Roman heritage. However, on the exterior apse of the church is a surprise. It has the rich geometry of Islamic tile patterns. Islamic artists who lived in the vicinity of Monreale were probably called upon to do this work.

|

| Islamic artisans decorated the eastern side of the church with rich geometric patterns |

The Greek artists who decorated the Cathedral’s interior were amongst the finest mosaic artists available. The Norman ruler may have brought these great artisans from Greece. Monreale Cathedral holds the second largest extant collection of church mosaics in the world. The golden mosaics completely cover the walls of the nave, aisles, transept and apse – amounting to 68,220 square feet in total. Only the mosaics at Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey, cover more area, although this cycle is better preserved. The narrative images gleam with heavenly golden backgrounds, telling the stories of Biblical history. The architecture is mainly western Medieval while imagery is Byzantine Greek.

|

| Mosaics in the nave and clerestory of Monreale Cathedral |

A huge Christ Pantocrator image that covers the apse is perhaps the most beautiful of all such images, appearing more calm and gentle than Christ Pantocrator (meaning “almighty” or “ruler of all”) on the dome of churches built in Greece during the Middle Ages. The artists adopted an image used in the dome of Byzantine churches into the semicircular apse behind the altar of this western style church. Meant to be Jesus in heaven, as described in the opening words of John’s gospel, the huge but gentle figure casts a gentle gaze and protective blessing gesture over the congregation. He is compassionate as well as omnipotent.

|

Christ Pantocrator, an image in the dome of Greek churches, spans the apse

of this western Romanesque church. |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 5, 2012 | Ancient Art, Exhibition Reviews, Greek Art, Memorials, Renaissance Art, Sculpture, The Middle Ages

An exquisite of exhibition “mourning” statues at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, have a beauty and realism that give us something to cry about, a phrase Michelangelo used to describe Flemish painting.

In the 15th century, Flanders was ruled by the Duke of Burgundy and similarities to the Flemish style of painting can be are apparent in the style of sculptors Jean de la Huerta and Antoine de la Moiturier. They learned their art from the great Claus Sluter, a Netherlandish sculptor who worked in Burgundy. The Dukes of Burgundy had one of Europe’s richest courts, in rivalry with the King of France to the west and Holy Roman Empire to the east.

The 40 statues line up as if in a funeral procession. At the exhibition, viewers have a chance to see the statues in more completeness and in a more realistic way than in the location they were originally placed, below the bodies of Duke John the Fearless (Jean sans Peur) and his wife, Marguerite. In the current display, the alabaster figures are seen as they move in space, without the elaborate decorative Gothic frames that confine them. They represent the clergy and family members who had been part of Jean the Fearless’ funeral procession in 1424. The statues are on loan from Dijon, France, while the Musee des Beaux Art is undergoing renovation.

Cowls and hoods identify these figures as mourners in the funeral procession. They are alabaster white with details such as books and belts painted. Larger effigies of the duke and duchess were painted in bright colors to look real.

Cowls and hoods identify these figures as mourners in the funeral procession. They are alabaster white with details such as books and belts painted. Larger effigies of the duke and duchess were painted in bright colors to look real.

Like Rogier van Weyden or the

Master of Dreux Budé , these sculptors drew on both realism and emotionalism in a style that is on the cusp between the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The figures are white with a few painted color details, although mourners and even horses, in the funerary procession actually wore black, hooded robes. A tomb of Philippe Pot, Seneschal of Burgundy, from about 1480 has life-size, hooded black figures which hold up the tomb and give an even more realistic version of a funeral.

Life-sized, hooded, black pallbearers were carved anonymously c. 1480 for the tomb of Philippe Pot, Seneschal of Burgundy. They have a greater sense of actuality but less individual, emotional pathos of the group in traveling exhibition.

Life-sized, hooded, black pallbearers were carved anonymously c. 1480 for the tomb of Philippe Pot, Seneschal of Burgundy. They have a greater sense of actuality but less individual, emotional pathos of the group in traveling exhibition.The small white, alabaster figures, however, are full of passionate emotion, and they move into a a variety of different positions. Their angular cuts of drapery are Gothic in style, but when seen in the round, as on display now, the statues have a 3-dimensional spatial conception of the Renaissance. Fortunately the artists carved them in the round, even though they are not seen this way in the Gothic niches underneath the life-sized, reclining duke and duchess. (In 1793, French revolutionaries damaged the effigies of the duke and duchess who represented the repression of the aristocracy, but left the mourners largely unharmed.)

The statuettes are part of the funerary sarcophagus of Jean sans Peur and Marguerite of Bavaria in the fine arts museum of Dijon. The small mourners walk in a funerary procession but are covered by gothic canopies.

These figures call to mind all the mourning figure in art history who accompany the processions and burials of important historical people, and remind us of the processions like those of Roman emperors. Certainly “mourners” were part of the history of art going back more than 5,000 years. However, I couldn’t think of any mourners from early Medieval art because the Early Christians felt death as triumphant and not a matter of earthly pain.

Although the Burgundian court was probably aware of ancient Roman sarcophagii depicting mourners in the funerary procession, the classical Greek-style Sarcophagus of the Mourning Women has a comparable format. This coffin of c. 350 BC was for a king of Sidon, Lebanon, and the women on bottom were probably part of his harem. Each mourner is carved in relief, standing separately between half-columns, while a chariots travel in a frieze above, perhaps the funerary procession or the rulers trip into afterlife. The women twist and  turn and cry to show their various expressions of grief after the death of a leader. As usual, these mourners serve a god-like ruler, not ordinary citizens.

turn and cry to show their various expressions of grief after the death of a leader. As usual, these mourners serve a god-like ruler, not ordinary citizens.

Eighteen women adorn the bottom of a sarcophagus of c. 350 BC, on view at that archeological museum in Istanbul

Early Greek funerary art attempts to show profound emotion. Both the ancient Greeks and Egyptians had elaborate burial ceremonies for their heroes or rulers that could last weeks or months. Mourners accompany pharoahs in their tombs, as the women below.

To the right, female “professional” mourners with raised arms who accompanied the great Ramses in his funerary procession are painted in his tomb.

Detail from a Greek vase in the Metropolitan Museum of Art has rows of mourning figures on either side of the funerary bier. Similar vases come from a cemetery in Athens and they date to 800-700 BC.

The lives of fallen Greek heroes were celebrated with elaborate games, chariot races and processions, as in the funeral sponsored by Achilles for the death of his friend Patrokles. Geometric style vases, from the 8th century BC, are decorated with scenes from funeral procession. Schematic, stick-like figures raise their arms to show they are grieving for the deceased. The figural design is a composite type: frontal torso, profile face and a single, huge eye.

Even older than Greek and Egyptian representations are two small terra cotta statues from Cernavoda, Romania, c. 4,000 BC. Found in a burial close to the Danube River, these statues could be mourning figures. The man’s arms are raised while the woman’s arm is on her knee, her shape suggesting fertility and hope for continuity. I can’t help but think these little figurines were made by the ancestors of Mycenaean or Dorian Greeks who in a later era migrated down into Greece.

The male figure is sometimes called “The Thinker,” but these clay figures from Cernavoda, Romania may be mourners who accompany an important person in burial. The raised arms to show grief was later used by Greeks. They also remind me of Brancusi and Henry Moore.

The exhibition stays until April 15 in Richmond, the last destination in a 2-year, 7-city tour in the United States, including the New York Metropolitan Museum. Next they will go to the Cluny Museum on Paris before returning home. It will be interesting to see how they are displayed when they go home to Dijon.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 8, 2011 | Caryatids, Erechtheion, Greek Art, Mythology, Sculpture, the Acropolis

Six famous women hold up the Porch of the Maidens of the Erechtheion, a temple on the Acropolis of Athens. These statues are admired for their graceful poses and drapery, but who notices the hair? An Art Historian who specializes in the sculpture of the Acropolis, Katherine Schwab, has studied the hairstyles and made a project of it for her students at Fairfield University in Connecticut. Here’s a summary of a presentation she gave last night at the Greek Embassy in Washington.

In the New Acropolis Mus eum, Athens –which was just built a few years ago — one can see the statues from the back with their beautiful long braids of hair, falling in fishtails followed by more curls. In fact, the hair of the statues is in better condition than the faces and bodies whose arms are completely missing. (Caryatid is the name given to a feminine statue which acts as a column to hold up a building; Kore is a statue of a maiden.)

eum, Athens –which was just built a few years ago — one can see the statues from the back with their beautiful long braids of hair, falling in fishtails followed by more curls. In fact, the hair of the statues is in better condition than the faces and bodies whose arms are completely missing. (Caryatid is the name given to a feminine statue which acts as a column to hold up a building; Kore is a statue of a maiden.)

These six caryatids are

labeled Kore A – Kore F.

Every hairstyle is a bit different. Most have fishtail braids down the back, along with regular braids wrapped around the head. Some of the caryatids have sidecurls, while others do not. Professor Schwab did the Caryatid Project with hai r stylist Miloxy Torres who recreated the braids on 6 students, all of whom had long, thick and mainly curly hair. The students acted out the caryatid poses other at the Fairfield University c

r stylist Miloxy Torres who recreated the braids on 6 students, all of whom had long, thick and mainly curly hair. The students acted out the caryatid poses other at the Fairfield University c ampus in 2009.

ampus in 2009.

The Porch of the Maidens adorns the Erechtheion which honors Athena, Poseidon, and two legendary kings Erechtheus and Krekops. It is an unusual building in many ways: three porches of different sizes going out in different directions. It was of special civic and religious significance to the ancient Athenians, because it marked the site of the contest between the god of the sea, Poseidon (Neptune) and Athena, goddess of war and wisdom, for control of Athens. In that competition presided over by legendary King Kekrops, Poseidon’s Neptune struck a hole on a rock to bring forth a spring of salt water. Nearby, in front of the building, Athena miraculously brought to life an olive tree. Athena’s gift was deemed greater and she became the ruler of Athens. One portion of the Erechtheion contains a wooden statue of Athena which fell from heaven during the reign of Erechtheus, but the Porch of the Maidens stands over the hole where Poseidon tapped his trident.

|

| The original caryatids are now on view in the New Acropolis Museum, Athens |

The photos are from the Caryatid

Project and Wikipedia. For more information and a video, see

www.fairfield.edu/caryatid Here’s the video

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

.jpg)

Recent Comments