by Julie Schauer | Aug 11, 2015 | Giorgio Vasari, Giuliano da Sangallo, Mythology, Piero di Cosimo, Renaissance Art

|

| Piero di Cosimo, Giuliano da Sangallo and Francesco Giamberti. The two-part painting was on loan from Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum recently. |

An exhibition of Renaissance painter Piero di Cosimo’s recently closed at the National Gallery in Washington a few months ago, and it’s taken me awhile to develop and express my understanding of him. Piero di Cosimo: The Poetry of Painting in Renaissance Florence continues a the Uffizi Gallery with a slightly different body of works in Florence, until September 27. It’s an interesting look at this quirky painter, someone who was living and working at the same time as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.

|

Piero di Cosimo’s Allegory, is part of the National Gallery’s

own collection. It is seen as an allegory of overcoming

one’s animal nature. |

Many of my students who wrote reviews of the exhibition dealt entirely with his religious paintings, the subjects you expect to see most often in Renaissance art. Like most Renaissance artists, Piero also did portraits. Some portraits, especially the diptych of Giuliano da Sangallo, architect, and Francesco Giamberti, musician, (above) are fabulous. Each part of the diptych is a separate window view of the subjects stand in front of deep landscape space. The colors radiant, the textures exquisite.

However, Piero is best known for his paintings of mythological allegories. Allegory in the National Gallery, left, is usually interpreted as a classical story of the choice between good and evil, also called The Dream of Scipio. There’s a winged female figure taming the wild horse. The animal is a reminder of the bestial side of nature. (Most men need to be tamed by women.) The half-human mermaid on bottom is swimming to the right.

|

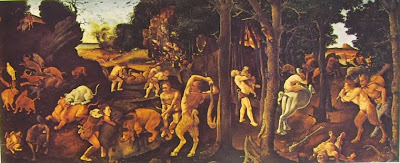

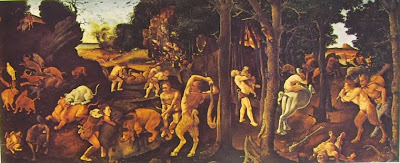

| Piero di Cosimo, The Hunting Scene, c. 1510, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

To me, his paintings are complex allegories of interrelated themes. Even the religious paintings carry the same themes as the mythological paintings. He’s very interested in man’s bestial nature, the choices between good and evil and the possibilities for transformation (redemption). Of interest are two scenes from the Metropolitan Museum. The Hunting Scene, (above) is web of animals fighting men and satyrs. It looks like two satyrs in front right have clubbed a man to death– a man who is radically foreshortened and ghostly pale. It is brutal, like The Battle of Ten Naked Men. According to the Metropolitan Museum, Piero was inspired by Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura.

|

| Return from the Hunt (detail) Metropolitan, NY |

Two rooms at the National Gallery were devoted to the mythologies, which I find to be his most imaginative and interesting works. Giorgio Vasari, the first Italian Renaissance art historian, writing after Piero died, explained the artist by saying,”It pleased him to see everything wild like his own nature.”

On the other hand, I see that Piero as relating his depictions primeval themes to Christianity. The sequel to the brutal hunting scene, Return from the Hunt, has a the detail (right), a man sitting in a tree that resembles the cross, and another man making or carrying a wooden cross like Simon. Is it somehow connected to Jesus’ crucifixion, even if Jesus and Simon aren’t there?Couples are falling in love. It would seem that Piero believes that even the wildest of men can be redeemed and overcome their animal nature.

It was common for Renaissance artists to do graphic compositions to show off their knowledge of one-point linear perspective. The Building of a Palace is Piero’s showpiece of perspective. This interesting demonstration of building methods has multiple activities going on at once. Another wooden cross is visible in the upper right, attached to a piece of machinery in front of the grand palace. He repeats the cross in what appears to be a secular scene, somewhat like the way Dutch artists of the 1600s put in their reminders of death and redemption. Surely the Christian message was important to Piero no matter how secular or pagan he seems.

|

| Piero di Cosimo, The Building of a Palace, 1515-20, Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida |

When Piero painted Perseus and Andromeda, a classical tale from Ethiopia, he picked up a theme not so different from the familiar Christian story of St. George and the Dragon.

|

| Perseus and Andromeda, 1510 or 1513, Uffizzi, Florence |

The National Gallery’s painting, The Visitation with St. Nicholas and S. Anthony, is one of Piero’s most famous paintings. Vasari describes the reflections on the balls of St. Nicholas as a reflection of the “strangeness of his brain.” After his teacher Cosimo Roselli died, Piero shut himself up and led a life less man than beast, according to Vasari. “He would never have his rooms swept. He would only eat when hunger came to him, and then only eggs. He boiled 50 eggs at a time, at the same time he boiled his glue for paint.”

|

| The Discovery of Honey, from the Worcester Art Museum |

Vasari further described Piero’s eccentricities. He was deathly afraid of lightning. Is it the real Piero, or something Vasari arrived upon by hearsay or by his own deduction? We will never know. “And he was likewise so great a lover of solitude, that he knew no pleasure save that of going off by himself with his thoughts, letting his dance roam and building his castles in the air.” The small mythological paintings, like The Invention of Honey, show his greatest gift as an artist: the ability to tell a story with allegorical content. Along with this storytelling ability, he had a wonderful capability of creating panoramas with perspective and integrating the figures into nature.

|

| Piero di Cosimo, Vulcan and Aeolus, c. 1500, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa |

Piero is better at painting panoramic allegories than painting figures on a larger scale. Sometimes the anatomy is weak and his foreshortening is inaccurate, as in Vulcan and Aeolus. Yet the painting is enchanting and brings us into a dreamworld where an unexpected mix of events takes place. A Dutch painter who lived at the same time, Heironymous Bosch, also painted giraffes he never may have seen. Like Bosch, he’s an ancestor of Surrealists. What was he thinking?

|

| The Myth of Prometheus, c. 1515, Alte Pinakothek, Munich |

We don’t know if Vasari’s description of Piero holds a grain of truth. What seems to be true, though, is that the conflict between good in evil is an essential part of Piero’s work. The reconciliation of Christianity to pagan themes is also essential to our understanding of him and other Renaissance masters. Zeus looks just like Jesus in The Myth of Prometheus. The theme is punishments from too much pride. Zeus is destroying the man fashioned by Prometheus and Prometheus’s brother is turned into a monkey in the upper left, and several scenes are conflated together. The artist is trying to find an analogy with Christian morality in the stories of the ancients. Zeus has the long hair, beard and red and blue clothes we associate with Jesus. (Having taken a class in Renaissance Neoplatonism and knowing writers of the time like Pico della Mirandola and Ficino, it’s clear that many Florentines thought of Christian themes and ancient themes as complimentary, like two sides of the same coin.)

|

Madonna with Jesus, St. John the Baptist, Sts. Jerome and

Bernard of Clairvaux |

A round tondo painting by Piero, Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist, St. Bernard of Clairvaux and St. Jerome, is lovely. It also has narrative dramas to illustrate the human struggle between good and evil in the middleground. St. Jerome is beating his chest to ward off temptation. The lion is shown with him, because St. Jerome tamed a lion. Behind St. Bernard, a devil is tied to a column, symbolizing the conquest of temptation. Another gorgeous religious painting tondo painting is in Tulsa, where the child Baptist gives his lamb to Baby Jesus.

|

Simonetta Vespucci, not in the NGA show

Musee Conde, Chantilly France |

The National Gallery show had exquisite paintings of Saint Mary Magdalene and St. John the Evangelist that looked like portraits. Their iconographic details show that Piero was influenced by the details and symbolism of Flemish artists. St. John holds a chalice with a snake a symbol attesting to his faith when the Romans asked him to swallow poison. Piero di Cosimo’s most famous portrait, a painting of the beautiful Florentine icon Simonetta Vesupucci, who died too young, was not in the National Gallery exhibition. Piero painted her as if bitten by an asp, like Cleopatra, on left. Again, he used the theme of snakes, which would seem to fit with his

His bacchanalian scenes had “strange fauns, satyrs, sylvan gods, little boys and bacchanals, that is is of marvel to see the diversity of the bay horses and gameness, and the variety of goat like creatures,” describes Vasari. There is a “joy of life produced by the great genius of Piero. There’s a certain subtlety by which he investigates some of the deepest and most subtle secrets of Nature, but only for his own delight and for his pleasure in art.”

|

| detail the Invention of Honey |

Vasari wrote more about Piero other artists who are considered even greater painters, namely Giorgione and Correggio. Vasari had a Florentine bias, and Piero was from Florence. Vasari also wrote, “If Piero had not been so solitary, and had taken more care of himself, he would have made known the greatness of his intellect in such a way that he would have been revered. By reason of his uncouth ways, he was rather held to be a madman.”

Piero was a wonderful eccentric who painted many imaginative and poetic mythologies. What links him to the best of the Renaissance is his lush colors, his landscapes and deep perspective. Some of his work is excellent but others stand out for their uneven quality. What breaks the mold for this time is when his mythologies reveal mankind’s delightful, bestial nature. Like the mannerist images Arcimboldo came up with later in the 16th century, his paintings teach us about the dark side of our human nature. In fact, his knarled branches look much like Arcimbolodo’s portrait of the The Four Seasons in One Head.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Jan 18, 2014 | Marc Chagall, Mosaics, Mythology, National Gallery of Art Washington

|

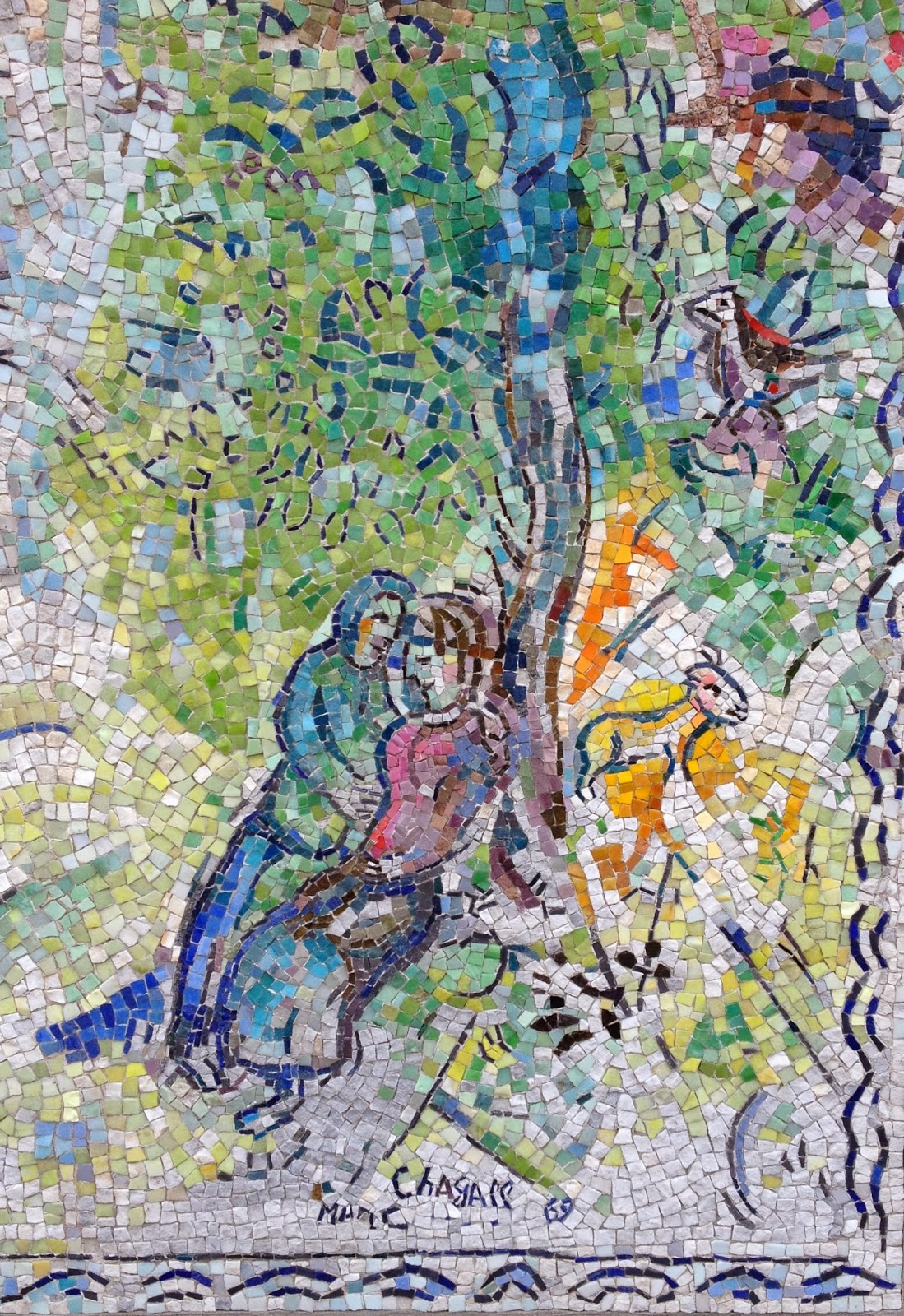

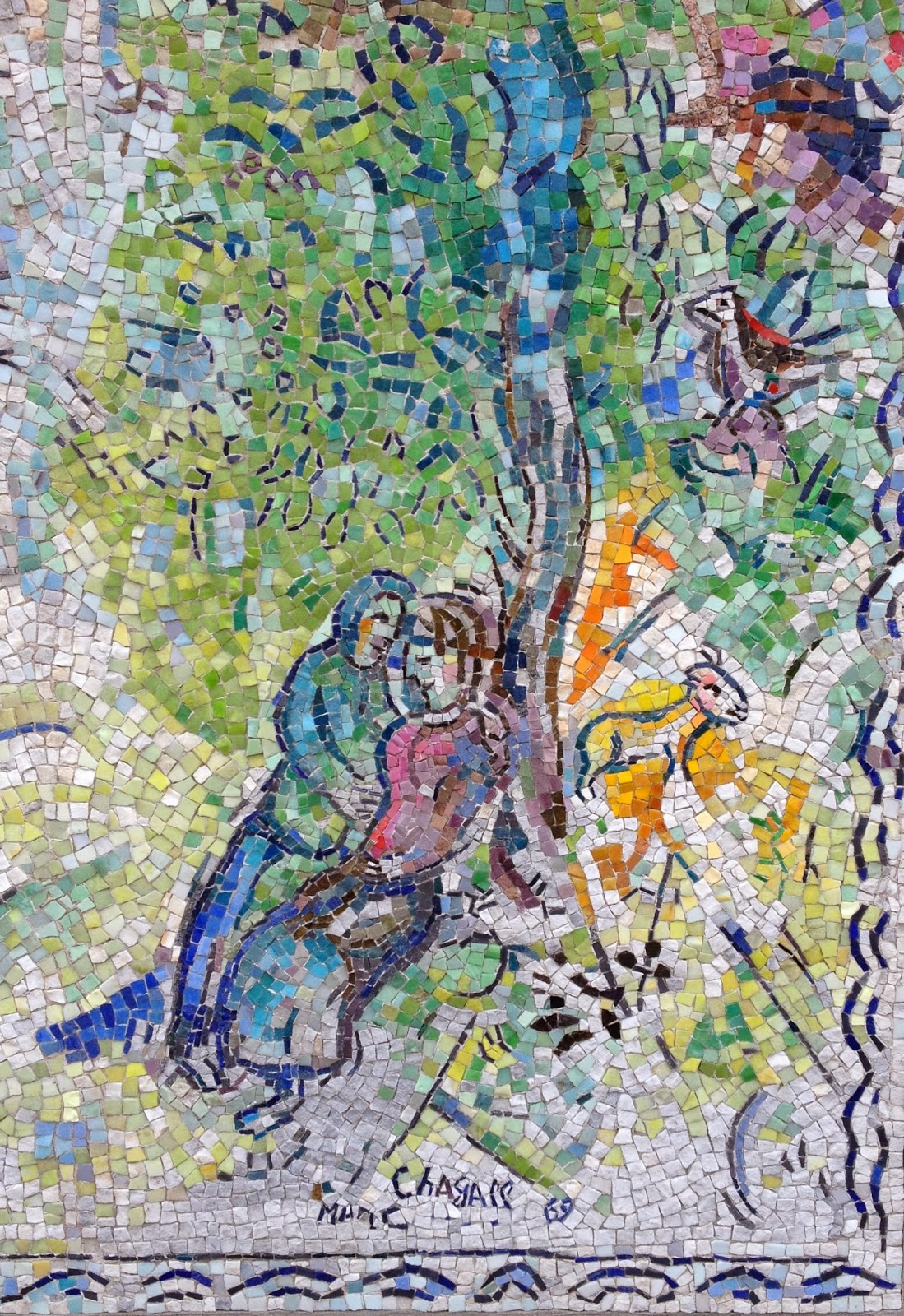

Detail – Marc Chagall, with Lino Melano, Orpheus, 1971, from the upper

right side–Pegasus, Three Graces, Orpheus

|

The nation’s capital city added a sudden burst of color this season in the form of Marc Chagall’s Orpheus, a glass and stone mosaic. It’s a 17′ by 10′ wall standing in the National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden, between 7th and 9th Streets, NW, Constitution Avenue and Madison Avenue. Evelyn Stephansson Nef, who died in 2009, donated it to the museum. (The composition is one of three new acquisitions in the National Gallery, a must-see along with a Van Gogh, a Gerrit von Honthorst and a loan of the Dying Gaul from the Capitoline Museum in Rome.)

The mosaic stands in the garden behind the restaurant, but in front of the heavily traveled Route 1. Fortunately, a lot trees shield it from view of the traffic, providing a reflective space for viewers. The sculpture garden is on the National Mall, but open only from 10-5 daily and 11-6 Sundays, except for an ice rink in winter which has longer hours.

Evelyn Nef and her husband, John Nef, were friends of the artist who was inspired after visiting them in 1968. The artist gave the mosaic to the couple back in 1971. For years, it was in the garden of their Georgetown residence, vaguely visible from the street. The National Gallery spent years preparing, repairing, moving and re-installing its 10 separate concrete panels, a process described in the Washington Post. The seams aren’t visible.

|

Detail, Marc Chagall, Orpheus, 1971. Here Orpheus

is crowned and holds his lyre. |

Chagall did the drawings for the composition in his studio back in France, and then hired mosaicist Lino Melano to complete it. Melano supervised installation which was finished in November, 1971. The artist returned at the time to see it. It was his first mosaic installed in the US. Afterwards, Chagall did the renowned Four Seasons mosaics for the First National Plaza in Chicago.

The composition has the spontaneity, verve and joy we can expect from Chagall. The execution, however, took a highly skilled Italian mosaicist who was steeped in the tradition. Melano used Murano glass, natural-colored stones and stones cut from Carrara marble. On close inspection, viewers can discern where there is glass: in the most brightly-colored passages, the shining blues, reds and radiant yellows. There is a touch gold leaf behind some of the glass, a technique inherited from the Byzantine mosaicists.

(For a good comparison, Byzantine mosaics are currently on view in the marvelous National Gallery Exhibition, Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Art from Greek Collections, until March 2, 2014.) Byzantine mosaics also combine stone cubes and glass cubes, called tesserae, but the tesserae are much, much smaller in Byzantine mosaics.

Melano wisely reserved the gold leaf for a few choice places, but only on Orpheus, his crown and his knee.

|

Detail, Marc Chagall, Orpheus, mosaic, 1971. Figures cross the ocean,

with an angel guide, the sun and mythological horse, Pegasus |

The god Orpheus is shown without his ill-fated mortal lover, Eurydice. Eurydice lost him because she disobeyed fate and dared to turn back and look at him while in the underworld. Chagall ignores the pessimistic part of the story. How then do we interpret what Chagall was trying to convey?

The other mythological figures are the flying horse Pegasus and the Three Graces. The winged-horse does not have feet, reminding me of the incomplete depictions of animals painted in the caves of southern France, near Chagall’s studio. Orpheus holds his lyre in a prominent position. Pegasus flies and Orpheus makes music while a little birdie flies. The Graces are not dancing here, but they remind us of our gifts and that grace is indeed possible. Chagall, who escaped Europe in the Holocaust, had a knack for putting a positive spin on events. He obviously chooses the highest potentials of human nature, while not exactly ignoring the negative.

|

| Detail, lower left corner with Chagall’s signature |

Of course the myth of Orpheus also conjures up images of the underworld. On the left, there is water where people are entering in groups and fishes are swimming. Could this be the River Styx of Greek mythology? Chagall said it referred to the groups of immigrants who crossed the ocean to get a better life. Above the river is a huge burst of sun. An angel flies triumphantly overhead, with open arms. The artist ignored the rules of perspective and foreshortening on this figure, reminding us that flight, or overcoming limitation, is indeed possible. He suggests that dreams can come true.

A dreaming couple on the bottom right hand side are happily in a paradise, under a tree. The artist’s signature is underneath. Chagall may have thought of himself with his wife, Bella. According to the National Gallery’s website, Evelyn Nef asked Chagall if this was her and her husband, John. He replied, “If you like.” There’s a border to the composition. Everywhere lines are curved, making this composition the image of life as a joyful journey, a graceful dance with much optimism.

|

Marc Chagall, Russian, 1887-1985, Orpheus, designed 1969, executed 1971, stone and glass mosaic

overall size: 302.9 x 517.84 cm (119 1/4 x 203 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

The John U. and Evelyn S. Nef Collection

2011.60.104.1-10 |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Oct 27, 2013 | Baroque Art, Diego Velázquez, Mythology, Old Testament, Paintings of Deception

|

| Diego Velázquez, Joseph’s Bloody Coat Brought to Jacob, 1630 oil on canvas, Monastery of San, Lorenzo, El Escorial, Spain, 87 3/4 x 98 3/8 in. wikipedia image |

Cheating card players and fortune tellers by Caravaggio and Georges de la Tour are among the best-known paintings of deception. Two extraordinary Velázquez paintings completed in 1630, The Forge of Vulcan and Joseph’s Bloody Coat Brought to Jacob, above, are also allegories of deception from the Baroque period of art.

Although a Biblical painting and a mythological painting would not seem connected, the canvasses match in height, format and the number of figures, six each. The painting of Jacob and sons has been cut at either end, while the other image has added canvas to the left. Both paintings have large window openings onto landscapes on their left sides. There are only male figures, many of them scantily dressed to show the artist’s extraordinary ability at depicting muscles of the arms, legs, back and chests with fine nuances of light and shadow. Joseph’s Blood Coat Brought to Jacob also has a barking dog.

Velázquez painted these pictures during his first of two trips to Italy, in 1630. In Italy, he seems to have been influenced by the frieze-like compositions of classical sarcophagi, which inspired him to spread his figures along the front of the composition, where the figures can be read from right to left or left to right.

Velázquez painted these pictures during his first of two trips to Italy, in 1630. In Italy, he seems to have been influenced by the frieze-like compositions of classical sarcophagi, which inspired him to spread his figures along the front of the composition, where the figures can be read from right to left or left to right.

In Joseph’s Bloody Coat Brought to Jacob, the lies and deception are still occurring. Joseph’s jealous brothers have sold him into slavery in Egypt, keeping his coat. They smeared blood of a goat on the beautiful coat and then told the father Joseph had been killed. While two of the brothers who are slightly darkened may evoke the shame, the two holding the coat are without remorse. They lie so easily, while a brother whose back faces us is feigning horror. Only five of Joseph’s ten older brothers are present. (More sons would ruin the format of the composition, but this omission also suggests that the other sons had remorse and couldn’t continue to carry out the deception in front of their father.)

In Joseph’s Bloody Coat Brought to Jacob, the lies and deception are still occurring. Joseph’s jealous brothers have sold him into slavery in Egypt, keeping his coat. They smeared blood of a goat on the beautiful coat and then told the father Joseph had been killed. While two of the brothers who are slightly darkened may evoke the shame, the two holding the coat are without remorse. They lie so easily, while a brother whose back faces us is feigning horror. Only five of Joseph’s ten older brothers are present. (More sons would ruin the format of the composition, but this omission also suggests that the other sons had remorse and couldn’t continue to carry out the deception in front of their father.)

Velázquez painted a vivid picture of poor Jacob, who favored Joseph among his sons. He is frightfully upset and disturbed. Below his foot, Jacob’s dog barks with a recognition of the duplicity taking place. The viewer can’t help but feel the old man’s crushing pain. Jacob is a tragic figure. Velázquez shows his ability to depict texture, especially in the carpet and the dog. He’s equally adept at showing an awareness of the dramas of human nature.

|

| Diego Velazquez, The Forge of Vulcan, 1630, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid, 87¾ in × 114⅛ in. Prado images |

|

In The Forge of Vulcan, the deception is announced by the sun god Apollo, who announces to Vulcan that Vulcan’s wife Venus, is cheating on him. The helpers at the iron forge show curiosity and shock. A young worker on the right, mouth ajar, is particularly comical in his spontaneous reactions. The god Vulcan bends vigorously and is upset. He’s all the more foolish because the announcement comes while he’s making armor for his wife’s lover, Mars, the god of war. It’s comedy more than tragedy, and Apollo, a tattle-tale, looks proud and gossipy.

Velázquez shows that he could portray comedy and he could paint real tragedy. He used his skills to reveal much about human nature, as well as Shakespeare had done writing plays in England two decades earlier. Velázquez’s brushstrokes capture amazingly realistic textures. The fire of the smelting iron, as well as the sheen of a vase and of armor, light up Vulcan’s blacksmith shop. Furthermore, he has painted the workmen closest to the fire in warmer skin tones, true to the colors that light from a fireplace would reflect on their flesh. The colors and sensibility in the entire scene are more earthy than the inside of Jacob’s palace.

Velázquez shows that he could portray comedy and he could paint real tragedy. He used his skills to reveal much about human nature, as well as Shakespeare had done writing plays in England two decades earlier. Velázquez’s brushstrokes capture amazingly realistic textures. The fire of the smelting iron, as well as the sheen of a vase and of armor, light up Vulcan’s blacksmith shop. Furthermore, he has painted the workmen closest to the fire in warmer skin tones, true to the colors that light from a fireplace would reflect on their flesh. The colors and sensibility in the entire scene are more earthy than the inside of Jacob’s palace.

While we may get a laugh at the gods of Mt. Olympus, we’re appalled and saddened by the behavior of Jacob’s sons. For an artist in pious Spain, deception in the Bible is tragic while deception in mythology becomes a comedy. Velazquez painted other mythological subjects, but his Bacchus is debauched and flabby, and Mars, god of war, is out of energy and depleted. Mythology is good for stories and subject matter but he didn’t always respect it as much as Italian artists like Titian, or French artists like Poussin.

While we may get a laugh at the gods of Mt. Olympus, we’re appalled and saddened by the behavior of Jacob’s sons. For an artist in pious Spain, deception in the Bible is tragic while deception in mythology becomes a comedy. Velazquez painted other mythological subjects, but his Bacchus is debauched and flabby, and Mars, god of war, is out of energy and depleted. Mythology is good for stories and subject matter but he didn’t always respect it as much as Italian artists like Titian, or French artists like Poussin.

Though I’ve never been to the Prado Museum in Madrid which has 45 Velázquez paintings, I had the good luck to see these beautiful images in a Velázquez exhibition at the Metropolitan in 1989. These two paintings knocked me the ground, I but didn’t understand how they were linked in meaning until reading the catalogue and other literature.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Sep 15, 2013 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Architecture, Greek Art, Knossos, Mythology

This summer I finally had the opportunity to go to Greece and see the sprawling Palace at Knossos. Actually, it’s not certain if this site was a palace, administrative center, giant apartment building, religious/ceremonial building, or all of the above. Yet it is so huge that, when discovered in 1900, archeologist Arthur Evans certainly thought he had found a true labyrinth where the legendary King Minos lived and kept his minotaur. The name Minoan for the Bronze Age people who lived in Crete from about 2000-1300 BC has stuck.

|

Covering 6 acres, the palace of Knossos and the surrounding city may have

had a population of 100,000 in the Bronze Age |

According to legend, the king of Athens paid tribute to King Minos by sending him 7 young men and young women who were in turn fed and sacrificed to the half-man, half-bull minotaur. Eventually, with the aid of Minos’ daughter and the inventor Daedalus, Theseus carried a ball of thread to find his way out and to slay the beast.

Although the art at Knossos doesn’t play out the precise myth, carvings and paintings found there involve imagery of bulls. Acrobats jumped and did flips over the animals’ horns, perhaps part religious ritual. It must have been an exciting but highly dangerous sport, and it’s easy to understand that as the story changed over time, later generations would envision a bull-headed monster in a spooky maze.

|

The palace at Knossos is on the hillside, about 5 kilometers from the sea. It was never fortified

Other, smaller palaces have been uncovered on the island. |

Could a prisoner escape without Theseus’ clever trick? Three or possibly four entrances to the palace are off-axis and may have appeared entirely hidden. The building also had windows, light wells, air shafts and ventilation. It was an engineering marvel. No wonder its architect Daedalus became a god to the Greeks. When I was there, it not only felt like a “labyrinth,” but also like “babel.” Its the only place I’d ever been where so many different, unfamiliar languages were being spoken at once. Despite the number of people, it never felt too crowded, because the palace covers six acres.

|

The downward taper of Minoan

columns is unusual but may have

religious significance. The capital

resembles the cushions of Doric

columns of Greece 1000 years later |

The building runs over 5 levels of twists and turns, on the hillside, not on top of a hill. It had 1300 rooms at one time and could have housed as many 5,000 people. There’s a large central courtyard, perhaps where crowds observed the bull-leaping sports. At least four other ancient maze-like palaces have been excavated on other parts of the island, but none as large as Knossos. It is thought that only 10% of Minoan Crete has been excavated and that bronze age Crete had 90 cities. I remember reading that Knossos had a population of at least 100,000 people around 1500 BC. Minoans traded with Egypt and Mesopotamia. Archaeologists have uncovered a Minoan colony in Egypt, Tel-el D’aba, and at Miletus in Turkey.

|

The North Entrance has a restored

fresco of a bull. Minoans were probably

the first to paint in fresco, on wet plaster |

Evans spent 35 years digging, researching and restoring the Palace of Knossos. The restoration reveals the Minoans’ unusual, downward-facing columns, with the narrowest parts on bottom. The earliest builders used the cypress tree and turned it over, so it wouldn’t grow.

There were both small frescoes and life-size frescoes, most of them now in the Archeological Museum in Heraklion, including the bull-leaping fresco. Since Egyptians painted in secco, on dry plaster, it’s believed that Minoans invented the fresco technique of painting on wet plaster. Colors such as blue, red and yellow ochre are very vivid. Generally Minoans painted with a freer and more organic style than the artists of Egypt and Mesopotamia, and often had more naturalistic depictions. However, whenever men or women are found marching with erect stiff postures, it’s conjectured that they functioned as priests and priestesses partaking in the religious rituals. There’s a famous bull-leaping fresco in the local museum.

|

| La Parisienne from Knossos |

|

|

|

Archeologists of today would not take as much liberty and restore as extensively as he did. While Evans pieced together restorations of the palace based on the remnants and shards, he also used his knowledge to restore what is missing. Personally I appreciate that his reconstruction fills in the blanks for us, giving an idea of the size and grandeur of the palace. Also, there’s a great deal to speculate as to what it may have been like to live there. It seems that grains, wine and olive oil may have been milled and pressed at the palace, and also stored in huge pithoi (giant vases) under the floor.

The word labyrinth originates from the labrys, a double-axe related to the double horns of the bull. The language used at the time the first palace was built, around the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, has not yet been deciphered. A second language which appeared at Knossos after mainland Greeks took over the palace after 1500 BC has been translated and is related to the classical Greek language

|

The life-size Prince of Lilies was thought by

Archeologist Arthur Evans to be a priest.

Lilies are common in Minoan imagery. |

All the inscriptions on cylinder seals are commercial records and inventories. Besides myth, the art and artifacts are the best way to figure out the story of these people. Only about 10 percent of the ancient Minoan sites have been excavated. Although the contents of the Archeological Museum of Heraklion, near Knossos, is well known and published, the beautiful pottery and artifacts from the museum of Chania, Crete’s next largest city, have not been published. Getting outside of the cities and into the countryside leaves the impression that the rural life really hasn’t changed too much in 1000 years.

|

The grand staircase at Knossos spans 5 levels. The layout of rooms is organic around a

central courtyard. What seems to be a haphazard arrangement may reflect

building and rebuilding after earthquakes. |

Certain things that date to the Mycenaean takeover of the palace include the Throne Room. Amazing, when the room was discovered, the gypsum throne was intact. Evidence points to the suggestion that the palace had to be abandoned all of a sudden, because of a fire, natural disaster or invasion. Even if this culture eventually went into oblivion for a few hundred years, when the Greek culture re-emerged around the 8th century BC, the Greeks culture retained so much of the Minoan heritage in its art and myth. The myths of the minotaur, Minos, Europa, Theseus, Daedelus and Icarus involve Crete, but so does the story of Zeus who was said to be born in Crete.

|

The Throne Room was found with oldest throne in

Europe, dating to Mycenaean occupation of Crete, around

1450-1400 BC. Evidence shows people had fled suddenly. |

Knossos has a theatre right outside the palace. Performances took place at the bottom of two seating areas set perpendicular to each other, rather than at the end of curved seating area as in later Greek theaters. The ancient Minoans also gave the world two important inventions, indoor plumbing and the potter’s wheel. Wouldn’t it be something if some of the first great Greek literary masterpieces also had an origin here, 1000 years earlier?

Occupation of the palace ended sometime between 1400 and 1100 BC. In the classical era Crete was never as important as Athens, though it is clear that much of what formed later Greek culture came from Crete. A settlement re-emerged in Knossos during Roman times, but during the Middle Ages the population shifted to the city of Heraklion, about 4-5 miles away.

|

| An area outside of the palace has two sets of seats set at a perpendicular angle. Acoustics indicate it was a theater. |

|

|

|

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 22, 2013 | Art and Literature, Art Appreciation: Visual Analysis, Baroque Art, Diego Velázquez, Fiber Arts, Mythology, Painting Techniques

|

Diego Velázquez, Las Hilanderas (The Spinners), oil on canvas, H: 220 cm (86.6 in) x W: 289 cm (113.8 in)

The Prado, Madrid |

(Not for beginning art students; I was not able to understand or interpret this painting at all until teaching a class in Mythology.)

The study of myths in all cultures, like the study of art, may seem obscure but it can illuminate some truths about humanity. Around the world, the beauty of weaving has some association with magic. So we look to Diego Velázquez’s Las Hilanderas (also called The Spinners, The Tapestry Weavers or The Fable of Arachne) which focuses on the weaving contest between Pallas Minerva and Arachne described in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The foreground scene is about a competition which includes spinning and carding, preparations that come before the weaving of tapestries. The final outcome of the story is implied, not shown. Velázquez used a complex composition of diagonals to weave a tale, a fable that lovers of Charlotte’s Web should appreciate.

Velázquez often put humor into his mythological scenes, but The Spinners is not a satire. It’s related in theme to Las Meninas (The Maids of Honor), considered by a majority of art experts to be the greatest secular painting of all time. The painterly effects of hair and material which dazzle us in Las Meninas go even further in The Spinners, which has a similarly complicated meaning. Its format is horizontal rather than vertical, but it also features a foreground and background for two tiers of storytelling connected by an opening of light and stairs. As Las Meninas is a group portrait disguised as everyday life in Velázquez El Escorial Palace studio, Las Hilanderas is a narrative posed as a genre scene in the dress styles or 17th century Spain. It’s dated one year after Las Meninas, 1657.

|

| Detail of Pallas Athena (Minerva) and a “spinning” wheel |

According to Ovid, Arachne was a girl born to humble parents in Lydia (an area of Turkey famous for beautiful weavings). She was reknown for her remarkable skill, but did not see her art as a gift from the goddess of weaving. Arachne accepted praise that set her above Pallas Minerva (Pallas Athena–also the goddess of wisdom) in the art of weaving. She said, “Let her compete with me, and if she wins I’ll pay whatever penalty.” So Pallas Athena disguised herself as an old crone, saying “Old age is not to be despised for with it wisdom comes…..seek all the fame you wish as best of mortal weavers, but admit the goddess as your superior in skill.”

Arachne wasn’t humbled and said “Why won’t (the goddess) come to challenge me herself?” Athena then cast off old age and revealed herself. Arachne was not scared and immediately took up the challenge of the competition. In foreground of Velázquez’s canvas, Athena (in a headscarf) and Arachne set up their spinning and carding operations in preparation for the weaving competition. At least three assistants are helping in the task. There are balls and balls of wool and thread and even a cat, but no looms in sight.

Just as Shakespeare liked to insert plays within his plays to elucidate the story, Velázquez was fond of putting subsidiary stories in his paintings. Another episode takes place in the background, although Velázquez skipped parts and hinted of the conclusion under the archway. Here Athena wears her goddess of war helmut. There are the same number of people in front as in back, five. It would be reasonable to believe that the young women in the back are the same assistants who help in the foreground, but have changed their clothing into fancy dresses. Only the lowly-born Arachne, furthest from the viewer, is modestly dressed.

|

From the girl “Fate” in shadow, we peer into a scene where Athena is about to strike Arachne.

Arachne’s belly is the center of the painting, hinting of the spider’s belly she will become. |

According to Ovid’s tale, when goddess and girl had completed their tasks, Athena revealed her tapestry with its central subject of Athena winning her competition with Poseidon to be the patron of Athens. She wove an olive vine from her sacred tree into the tapestry’s border. Secondary scenes showed the power of gods and goddesses as they triumphed over humans. The subject of Arachne’s tapestry was stories of trickeries by gods and goddesses, at the expense of mortals. She had shown as her central subject as the rape of Europa by Zeus in the form of a bull. This scene is recognized in the back of this painting as a replica of Titian’s famous painting of that subject in the Spanish royal collection.

“Bitterly resenting her rival’s success, the goddess warrior ripped it, with its convincing evidence of celestial misconduct, all asunder; and with her shuttle of Cytorian boxwood, struck at Arachne’s face repeatedly.” In the painting, Athena holds her shuttle in the foreground, not the background, but Velázquez cleverly placed it in Athena’s left hand where it points to the next image of Athena in armor. Velázquez highlighted the goddess’s anger against a light blue background and emphasized the force of Athena’s striking arm. Arachne’s head is nearly the center of the painting, but the viewer realizes she will exist no longer. “She could not bear this, the ill-omened girl, and bravely fixed a noose around her throat: while she was hanging, Pallas, stirred to mercy, lifted her up and said:

“Bitterly resenting her rival’s success, the goddess warrior ripped it, with its convincing evidence of celestial misconduct, all asunder; and with her shuttle of Cytorian boxwood, struck at Arachne’s face repeatedly.” In the painting, Athena holds her shuttle in the foreground, not the background, but Velázquez cleverly placed it in Athena’s left hand where it points to the next image of Athena in armor. Velázquez highlighted the goddess’s anger against a light blue background and emphasized the force of Athena’s striking arm. Arachne’s head is nearly the center of the painting, but the viewer realizes she will exist no longer. “She could not bear this, the ill-omened girl, and bravely fixed a noose around her throat: while she was hanging, Pallas, stirred to mercy, lifted her up and said:

“Though you will hang, you must indeed live on, you wicked child; so that your future will be no less fearful than your present is, may the same punishment remain in place for you and yours forever!” Then, as the goddess turned to go, she sprinkled Arachne with the juice of Hecate’s herb, and at the touch of that grim preparation, she lost her hair, then lost her nose and ears; her head got smaller and her body, too; her slender fingers were now legs that dangled close to her sides; now she was very small, but what remained of her turned into belly, from which she now continually spins a thread, and as a spider, carries on the art of weaving as she used to do.” Note that the belly of Arachne which will be the spider’s core is at the exact center of the painting.

|

| The Spinners, right side, detail of Arachne |

With the fable explaining the origin of spiders, it makes sense that the preparatory activity in the foreground is all about the thread (and the spinning of fate), because there is so much winding to that thread. I interpret the young helpers to Arachne and Pallas Athena as the three Fates. The Fates can be described as Moira in singular name, or Moirai. Their specific names are Clotho meaning “Spinner,” Lachesis, who measures the thread, and Atropos who is inflexible and cuts it off. The three Fates are goddesses and daughters of Zeus who are sometimes considered more important than Zeus in their ability to seal destiny. They come in various disguises, and wouldn’t be surprising if these young women seen as helpers are really the ones who ultimately are in charge. In myth and life, there is always the question of how much free will or how much fate determines outcome.

Velázquez uses highlights and shadows strategically for his story telling goals. Arachne stands out because she is highlighted to a much greater degree than Minerva is, yet we see nothing of her face. How ironic that he, Velázquez who proudly showed his face in Las Meninas, his allegory of painting, does not allow Arachne to show hers. Her back is to us, as she labors deftly and diligently. Both Athena and Arachne are barefoot. The goddess, who is older though not an old lady, even shows some leg!

One of the women in the background is looking back to the foreground, a complexity that pulls the composition together. Perhaps she had been the only one of three Fates who supported Arachne and was pulling strings for her. The woman or Fate dressed in blue shows her back to the viewer, but she appears again immediately below in the foreground, though separated by stairs. Here Velázquez has deliberately darkened her face in shadow, in deeper shadow than is necessary for the composition. As in other Velázquez paintings, shadowed figures can signify that a character in the painting is an actor, an actor who is playing a role in an act of deception. Though she aids Arachne in the guise of as a common peasant girl, her concern with thread could actually be in the process of spinning a different fate.

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, Pallas and Arachne, oil, 1634, at Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond |

Velazquez was familiar with the fable of Arachne from a Peter Paul Rubens painting of Pallas and Arachne which was owned by the Spanish royal family. The Rubens composition is more violent, with Pallas Athena striking Arachne to the ground. A copy of this painting was in the background of Las Meninas, Velázquez’s most famous painting of 1656, a composition which raises the status of art and the artist. Velázquez must have thought of the art of weaving as a noble pursuit, similar to the art of painting. Both require exceptional talent and skill. Weaving and spinning have additional, magical connotations in mythology, such as the woven clothing of goddesses, the weavings of Odysseus’ wife and the thread which let Theseus out of the labyrinth. Velázquez was a great artist, but, like the prodigy Arachne, he was not of noble birth.

|

Detail of self-portrait in Las Meninas, with

the red cross added later |

|

|

Las Meninas — which contains a portrait of the artist in the act of painting — is about the role of the artist, the origins of creativity and the attainment of status. The Spinners further explores these subjects and elucidates some of the same ideas. Our talents are divine gifts and, as mortals, there are limitations on us. No matter what the artist’s genius is, there are warnings against boasting. In the end, we are left with a reminder of the punishment which comes from carrying pride too far.

The paintings compare artistry and skill, and the status of the artist, to the non-negotiable status of higher beings, i.e., the Spanish Royal family, and an Olympian goddess. There is a crucial difference, however. Arachne, an upstart weaver, was just a girl when she challenged the goddesses of wisdom and weaving and the Fates. Velázquez, on the other hand, was 56 when he painted Las Meninas, and his self-portrait looks outward asserting the importance due to him. Remember how Athena in the guise of an old lady had warned Arachne that with old age comes wisdom.

|

Velázquez, The Water Seller of Seville, c. 1620

Apsley House, London |

Velázquez had also been an extraordinary prodigy, only about 20 when he painted The Water Seller of Seville. There, an elderly man is passing a glass of water to an adolescent boy while a young adult man stands behind. It was nearly 40 years later that he finally gained knighthood status, the Order of Santiago. A red cross, painted on his chest three years after completing Las Meninas, indicates that title he attained shortly before death in 1660. However, from Velázquez’s other paintings, we know he treated royalty and peasant with equal respect and dignity. The old man in The Water Seller of Seville wears a torn cloak indicating his humble means compared to the young boy he serves. So it is not Arachne’s lowly birth, but her youthful pride which denied the wisdom of age that Velázquez sees as her ultimate downfall. The attainment of greatness is possible if one waits, for only with age comes wisdom.

Velázquez’s stylistic change over the years from tight and controlled to very painterly is typical. He painted two allegories of deception, one mythological, when he was around 30 and in Rome, a turning point in his career. (You can some of the changes of his style from early to middle and late in a blog about him.)

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Sep 1, 2012 | 19th Century Art, Art and Literature, Cezanne, Exhibition Reviews, Franz Marc, Gauguin, Giorgione, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Landscape Painting, Matisse, Modern Art, Mythology, Nicolas Poussin

One of the first ‘pastoral‘ paintings(not in the exhibition) was

The Pastoral Concert, 1509, by Titian and/or

Giorgione, originator of the pastoral, where landscape is on par with figures. Shepherds and musicians are frequent in this theme.

Good things always end, including summer and a chance to see how the greatest modern artists painted themes of leisure as Arcadian Visions: Gauguin, Cezanne, Matisse, ends Labor Day.

The exhibition highlights 3 large paintings: Gauguin’s frieze-like Where do We Come From?…, 1898, Cézanne’s Large Bathers, 1898-1905 and Matisse’s Bathers by a River, 1907-17.

Each painting was crucial to the goals of the artists, and crucial to the transitioning from the art and life of the past into the 20th century. These modernist visions actually are part of a much older theme descended from Greece and written about in Virgil’s Eclogues. Nineteenth-century masters were very familiar with this tradition from the 16th-century painting in the Louvre, The Pastoral Concert, by Giorgione and/or Titian. Édouard Manet’s infamous Luncheon on the Grass of 1863 was probably painted to fulfill that artist’s stated desire to modernize The Pastoral Concert. Those who think artists throw away tradition, think again; the greatest artists of the modern age did not.

Arcadia was originally thought to be in the mountains of central Greece. Virgil described a place where shepherds, nymphs and minor gods who lived on milk and honey, made music and were shielded from the vicissitudes of life. With its promise of calm simplicity, Arcadia was a place of refuge. Renaissance scholars writers and painters re-descovered it; Baroque painters developed the theme further, and 19th century artists glorified it because the Industrial created yearnings for a simpler life. (Musée d’Orsay in Paris has a small focused exhibit on Arcadia at the moment.) Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem of 1876, An Afternoon of the Faun, had this theme, too, and was followed by Claude Debussy’s musical interpretation after that poem.

But, even Virgil had warned, that things are not always as they seem. The exhibition’s signature pieces by Gauguin, Cézanne and Matisse reflect harmonious relationships between humans and nature, but tinged with loss. The best of Arcadian visions give equal importance to figures and landscape, as these artists do. Other 19th century painters, whose work is shown for comparison, include Corot, Millet, Signac, Seurat, and Puvis da Chavannes. It is interesting that the museum did not include Auguste Renoir’s Large Bathers, 1887, in the PMA’s own collection, probably because that idealized scene does not have anything foreboding.

Paul Gauguin, Where do we come From? Who Are We? Where Are We Going?(detail of left side), 1898

From the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is so large that it must be seen in real life.

Artist Paul Gauguin escaped France and settled in the the south seas, Tahiti, where he searched for his version of Arcadia. It was the first time I had seen Gauguin’s Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going? No reproduction does justice to its color, details and beauty. Twelve five feet wide and four feet high, it must be seen in person to adequately “read the painting.” Composed of figures familiar from other Gauguin paintings, this allegory makes us think deeply about the meaning of life via Gauguin’s favorite figural types, the women of Tahiti. He depicts youth, adulthood and old age and treats each phase as a moment of discovery and passing to the next, but we may end up with more questions than answers.

Paul Cézanne, The Large Bathers, 1898-1906, Philadelphia Museum of Art, is the

culminations of many studies he had been doing of bathers since the 1870s.

The acoustical guide to the exhibition quotes Paul Gauguin who said that Paul Cézanne spent days on mountaintop reading Virgil. Cézanne’s soul was always in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence and the connection to that past was in his blood, coming from a very classical childhood education of Latin and Greek and hiking through old Roman paths with friend and future novelist, Émile Zola. Even though the bathers have no sensuality, Cézanne’s Large Bathers is a painting which gives exquisite beauty to its concept. To me, it stands out as the most important painting in the show. An article links Cézanne to thoughts of death, Poussin and several poets who wrote of the territory surrounding Aix as Arcadia. This painting is perhaps the most Arcadian modern painting of the exhibition, although there are no shepherds, no musicians and no men. While it picks up the dream of humankind living simply in nature, under its beauty and its bounty, one woman points to the river, suggesting a place where these complacent bathers will ultimately go.

The design of The Large Bathers perfectly balances traditional space and compositional structure with the goals of modern art. I always knew how much I loved this painting, but now I know why. The exhibition gave me much new insight and appreciation to fill an entire blog about this painting. Matisse’s painting is in the same large room of the exhibition, but the message is less subtle.

Matisse spent ten years revising this painting, 8’7″ by 12’10” Art Institute of Chicago

He completed Bathers by a River around 1917

Bathers by a River is also very large and, as expected, even more abstract. Matisse worked on the painting for 10 years and changed it, as his ideas and conceptions changed. Noticeable is the lack of color and empty features of the faces. He paints verticals, a suitable balance to the curves, but a snake appears in front and in the center, which can be seen as a dire warning. World War I was happening at the time he finished it. His earlier paintings of bathers were far more joyful and colorful.

Henri Rousseau, The Dream, 1910, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

is approximately 6’8″ x 9’9″

It was a complete surprise to see Henri Rousseau’s The Dream, also a very large painting. The tropical landscape with an elephant and lions is included in the same room of monumental paintings. Rousseau drew exotic plants in the botanical gardens of Paris and he painted them in a simplistic style with unexpected, evocative juxtapositions. He was a visionary before the Surrealists. His woman reclines in a traditional pose on a seat-less sofa, as a dark-skinned horn player and jungle animals appears. Music, repose, luxury of nature are typical Arcadian themes, and it is a joy to see it in the same room with the three signature paintings of the exhibition.

Nicolas Poussin, The Grande Bacchanal, c. 1627, from the Louvre, Paris

To understand all these connections, the curator included a painting by the most representative painter of the Arcadian tradition, Nicolas Poussin. (New York’s Metropolitan Museum hosted an exhibition, Poussin and Nature: Arcadian Visions, 4 years ago.) Poussin was a Baroque artist who was thoroughly engrossed in a classical style with themes taken from ancient writers. His painting The Grande Bacchanal, 1627, on loan from the Louvre, has beautiful women, musicians, a Silenus and even baby revelers, with darkess approaching the landscape. Each of the early modern artists featured in the exhibition were familiar with Poussin’s style and sources, as well as Watteau and Boucher who painted pastoral themes in the 18th century.

Matisse’s early Fauvist paintings, Music and The Dance, are abstract and modern but thoroughly a part of the pastoral tradition. Athough the exhibition does not show any of the colorful compositions Matisse did in the first decade of the 20th century, those paintings have tons of color and are steeped in the pastoral tradition. (I’ll need to take trip to Philadelphia to see the Barnes Collection with another large version of Cézanne’s Bathers and Matisse’s famous The Joy of Life.)

A sketch of “Music” from MoMA links back to Poussin’s The Andrians, with dancers, a lounging woman and a violinist. This painting is not in the exhibition..

Quotes from the poet Virgil’s pastoral literature line the walls. We witness how various artists of the 19th and 20th centuries interpreted his poetry in drawings, paintings, etchings and illustrated books. The exhibition ends with Picasso, Cubists, Expressionists and little-known Russian painters of the 20th century. Although not always inspired by Virgil or Ovid, these paintings can be linked to the desire for a bucolic life of simplicity and harmony in nature.

I was awed to see the Robert Delaunay’s City of Paris, 1910-12. Delaunay famously painted the Eiffel Tower in a Cubist jumble of colors and shifting perspectives. That symbol of modernism was only a little more than 20 years old at this time. This giant canvas of Paris also has three large nudes. They are the Three Graces, just as Botticelli and Raphael had painted them. Delaunay’s vision of Paris includes the past and the present, but the nudes of the past are actually seem more central to this composition of shifting triangles, circles and planes of colors. If anything, Cubism reminds us of life’s impermanence.

Robert Delaunay, City of Paris, 1910-12, is 8’9″ x 13’4″

Finally, at the end we see

Franz Marc’s Deer in Forest, II, from the Phillips Collection. Here the humans are gone and only animals are in the forest. The exhibition is very thoughtful and reflective, and I thank Curator Joseph Rishel for giving us so much to ponder. It is one designed not only to make us only look art more closely, but we must also think more deeply.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments