by Julie Schauer | Dec 13, 2015 | Gauguin, Picasso, Rouault

|

Paul Gauguin, NAFAE faaipoipo (When Will You Marry?) 1892

Rudolph Staechelin Collection |

The Phillips Collection’s latest loan exhibition, “Gauguin to Picasso: Masterworks from Switzerland,” draws upon a pair of collections assembled by two prominent but very different Swiss art collectors. To me, the theme of dualism, pairs and split identities stands out strongly. The exhibition highlights one of Gauguin’s most famous paintings, When are You to be Married? — a painting that recently was sold. (The Staechelin and Im Oberstag collections of modern art are normally on display at the Basel Kunstmuseum. Here’s an article for background on the collectors why the paintings are traveling.)

Like so many other paintings by Gauguin, the two women in this infamous painting express two realities, which could represent the split identities within Tahitian society. He painted it during his first stay in Tahiti in 1892. The woman in front is natural, organic, relaxed and colorful in her red skirt. The orchid in her hair was said to suggest that she is looking for a mate. A woman behind is taller, more severe and covered in a pink dress buttoned to the top–an influence of Western missionaries. The woman in back has a bigger head than the woman in front. Does he mean to imply that she dominates? Or, is Gauguin imagining a single Tahitian woman who is torn between her native identity and the invasion of western civilization.

|

| Eugene Delacroix, Women of Algiers, 1834, The Louvre |

The woman in front may be inspired by one of the very beautiful, sensual women painted in Delacroix’s Women of Algiers, one of my all-time favorite paintings. (Delacroix was allowed into the mayor’s harem to sketch the women–pictured at right. Like Gauguin, Delacroix was European observing women in an exotic, foreign land.)

|

| Gauguin, Self-Portrait, 1889, NGA |

|

|

|

|

In his self-portraits and so much of his art, Gauguin expresses the split nature in mankind, the areas where there is inner conflict. Symbolist Self-Portrait at the National Gallery of Art (NGA), Washington, is a divided person, both a saint and a sinner. He has a choice in the matter, and we wonder what he’ll choose.

The two Tahitian women are different, yet blended. Warm brown skin tones unite them and the hot red skirt of the “natural” native woman flawlessly flows into the warm pink of the stiffer, “civilized” woman. The colors blend and contrast simultaneously into a beautiful harmony. (Is it surprising that this picture was the most expensive painting ever sold? Rumor has it that it was purchased by a Qatari for Qatar Museums.)

|

| Georges Rouault, Landscape with Red Sail, 1939, Im Obersteg Foundation, permanent loan to the Kunstmuseum Basel. Photo © Mark Gisler, Müllheim. Image © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris |

Other artists in this exhibition continue the theme of duality and split personality. Early 20th century Expressionist Georges Rouault was honest about his identity as a person belonging in another century, the age of the cathedrals. His heavily-outlined Landscape with Red Sail uses colors reminiscent of the colors in stained glass and the way stained glass is divided by lines of lead. Yet, his paint is applied in a very rough, heavy manner, hardly like the smoothness of glass. His beautiful seascape does, however, evoke the light of a sunset peaking behind the sailboat–like the light filtering in medieval churches.

|

| Alexej Jawlensky, Self-Portrait, 1911 Im Obersteg Collection |

|

|

The Expressionist painter Alexej von Jawlensky was a Russian living in Switzerland, in exile there during World War I. There’s a haunting quality to his Self-Portrait, left. Jawlensky and Im Obersteg had a strong friendship throughout his career.

One side of a Picasso painting features a woman in a Post-Impressionist style, “Woman At the Theatre,” and the other side has a sad woman, The Absinthe Drinker, from the beginning of the “Blue period.” Both were painted in 1901. They could not be more different from each other. Picasso was very experimental at that

|

| Picasso, The Absinthe Drinker, 1901 Im Obersteg Collection |

|

|

time of his life and in his career.

Expressionism is a large part of the exhibition, especially with Wassily Kandinsky, Chaim Soutine, Marc Chagall and Alexej von Jawlinsky. Swiss Symbolist Ferdinand Hodler shares with us his experience of love and death in a group of paintings of his dying lover Valentine Gode-Darel. It is difficult to watch and for him painting may have been an attempt to make peace with the awful situation.

The series of paintings by Hodler are some of the most powerful in the exhibition because we experience the unfolding of a tragedy. Gode-Darel died of cancer in

|

| Ferdinand Hodler, The Patient, painted 1914, dated 1915. The Rudolf Staechelin Collection © Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler |

1915, a year after diagnosis. The three paintings of rabbis by Marc Chagall continue in the theme of portraiture.

There are very fine small paintings by Cezanne, Monet, Manet, Renoir and Pissaro, two beautiful landscapes by Maurice de Vlaminck. Van Gogh’s, The Garden of Daubigny, 1890 is one of three he did of the same subject weeks before his death. The black cat in the painting is small but curiously out of place. The 60 paintings on view, on view until January 10 — are worth the trip to the Phillips. Here are some of the best photographs of the paintings in the show. These Swiss collections complement the Phillips own marvelous collection of early Modernism. It is curious that the Swiss collections don’t show the greatest of all 20th century Swiss artists, Paul Klee.

|

| Vincent Van Gogh. The Garden of Daubigny, 1890 Rudolf Staechelin Collection |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Sep 1, 2012 | 19th Century Art, Art and Literature, Cezanne, Exhibition Reviews, Franz Marc, Gauguin, Giorgione, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Landscape Painting, Matisse, Modern Art, Mythology, Nicolas Poussin

One of the first ‘pastoral‘ paintings(not in the exhibition) was

The Pastoral Concert, 1509, by Titian and/or

Giorgione, originator of the pastoral, where landscape is on par with figures. Shepherds and musicians are frequent in this theme.

Good things always end, including summer and a chance to see how the greatest modern artists painted themes of leisure as Arcadian Visions: Gauguin, Cezanne, Matisse, ends Labor Day.

The exhibition highlights 3 large paintings: Gauguin’s frieze-like Where do We Come From?…, 1898, Cézanne’s Large Bathers, 1898-1905 and Matisse’s Bathers by a River, 1907-17.

Each painting was crucial to the goals of the artists, and crucial to the transitioning from the art and life of the past into the 20th century. These modernist visions actually are part of a much older theme descended from Greece and written about in Virgil’s Eclogues. Nineteenth-century masters were very familiar with this tradition from the 16th-century painting in the Louvre, The Pastoral Concert, by Giorgione and/or Titian. Édouard Manet’s infamous Luncheon on the Grass of 1863 was probably painted to fulfill that artist’s stated desire to modernize The Pastoral Concert. Those who think artists throw away tradition, think again; the greatest artists of the modern age did not.

Arcadia was originally thought to be in the mountains of central Greece. Virgil described a place where shepherds, nymphs and minor gods who lived on milk and honey, made music and were shielded from the vicissitudes of life. With its promise of calm simplicity, Arcadia was a place of refuge. Renaissance scholars writers and painters re-descovered it; Baroque painters developed the theme further, and 19th century artists glorified it because the Industrial created yearnings for a simpler life. (Musée d’Orsay in Paris has a small focused exhibit on Arcadia at the moment.) Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem of 1876, An Afternoon of the Faun, had this theme, too, and was followed by Claude Debussy’s musical interpretation after that poem.

But, even Virgil had warned, that things are not always as they seem. The exhibition’s signature pieces by Gauguin, Cézanne and Matisse reflect harmonious relationships between humans and nature, but tinged with loss. The best of Arcadian visions give equal importance to figures and landscape, as these artists do. Other 19th century painters, whose work is shown for comparison, include Corot, Millet, Signac, Seurat, and Puvis da Chavannes. It is interesting that the museum did not include Auguste Renoir’s Large Bathers, 1887, in the PMA’s own collection, probably because that idealized scene does not have anything foreboding.

Paul Gauguin, Where do we come From? Who Are We? Where Are We Going?(detail of left side), 1898

From the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is so large that it must be seen in real life.

Artist Paul Gauguin escaped France and settled in the the south seas, Tahiti, where he searched for his version of Arcadia. It was the first time I had seen Gauguin’s Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going? No reproduction does justice to its color, details and beauty. Twelve five feet wide and four feet high, it must be seen in person to adequately “read the painting.” Composed of figures familiar from other Gauguin paintings, this allegory makes us think deeply about the meaning of life via Gauguin’s favorite figural types, the women of Tahiti. He depicts youth, adulthood and old age and treats each phase as a moment of discovery and passing to the next, but we may end up with more questions than answers.

Paul Cézanne, The Large Bathers, 1898-1906, Philadelphia Museum of Art, is the

culminations of many studies he had been doing of bathers since the 1870s.

The acoustical guide to the exhibition quotes Paul Gauguin who said that Paul Cézanne spent days on mountaintop reading Virgil. Cézanne’s soul was always in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence and the connection to that past was in his blood, coming from a very classical childhood education of Latin and Greek and hiking through old Roman paths with friend and future novelist, Émile Zola. Even though the bathers have no sensuality, Cézanne’s Large Bathers is a painting which gives exquisite beauty to its concept. To me, it stands out as the most important painting in the show. An article links Cézanne to thoughts of death, Poussin and several poets who wrote of the territory surrounding Aix as Arcadia. This painting is perhaps the most Arcadian modern painting of the exhibition, although there are no shepherds, no musicians and no men. While it picks up the dream of humankind living simply in nature, under its beauty and its bounty, one woman points to the river, suggesting a place where these complacent bathers will ultimately go.

The design of The Large Bathers perfectly balances traditional space and compositional structure with the goals of modern art. I always knew how much I loved this painting, but now I know why. The exhibition gave me much new insight and appreciation to fill an entire blog about this painting. Matisse’s painting is in the same large room of the exhibition, but the message is less subtle.

Matisse spent ten years revising this painting, 8’7″ by 12’10” Art Institute of Chicago

He completed Bathers by a River around 1917

Bathers by a River is also very large and, as expected, even more abstract. Matisse worked on the painting for 10 years and changed it, as his ideas and conceptions changed. Noticeable is the lack of color and empty features of the faces. He paints verticals, a suitable balance to the curves, but a snake appears in front and in the center, which can be seen as a dire warning. World War I was happening at the time he finished it. His earlier paintings of bathers were far more joyful and colorful.

Henri Rousseau, The Dream, 1910, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

is approximately 6’8″ x 9’9″

It was a complete surprise to see Henri Rousseau’s The Dream, also a very large painting. The tropical landscape with an elephant and lions is included in the same room of monumental paintings. Rousseau drew exotic plants in the botanical gardens of Paris and he painted them in a simplistic style with unexpected, evocative juxtapositions. He was a visionary before the Surrealists. His woman reclines in a traditional pose on a seat-less sofa, as a dark-skinned horn player and jungle animals appears. Music, repose, luxury of nature are typical Arcadian themes, and it is a joy to see it in the same room with the three signature paintings of the exhibition.

Nicolas Poussin, The Grande Bacchanal, c. 1627, from the Louvre, Paris

To understand all these connections, the curator included a painting by the most representative painter of the Arcadian tradition, Nicolas Poussin. (New York’s Metropolitan Museum hosted an exhibition, Poussin and Nature: Arcadian Visions, 4 years ago.) Poussin was a Baroque artist who was thoroughly engrossed in a classical style with themes taken from ancient writers. His painting The Grande Bacchanal, 1627, on loan from the Louvre, has beautiful women, musicians, a Silenus and even baby revelers, with darkess approaching the landscape. Each of the early modern artists featured in the exhibition were familiar with Poussin’s style and sources, as well as Watteau and Boucher who painted pastoral themes in the 18th century.

Matisse’s early Fauvist paintings, Music and The Dance, are abstract and modern but thoroughly a part of the pastoral tradition. Athough the exhibition does not show any of the colorful compositions Matisse did in the first decade of the 20th century, those paintings have tons of color and are steeped in the pastoral tradition. (I’ll need to take trip to Philadelphia to see the Barnes Collection with another large version of Cézanne’s Bathers and Matisse’s famous The Joy of Life.)

A sketch of “Music” from MoMA links back to Poussin’s The Andrians, with dancers, a lounging woman and a violinist. This painting is not in the exhibition..

Quotes from the poet Virgil’s pastoral literature line the walls. We witness how various artists of the 19th and 20th centuries interpreted his poetry in drawings, paintings, etchings and illustrated books. The exhibition ends with Picasso, Cubists, Expressionists and little-known Russian painters of the 20th century. Although not always inspired by Virgil or Ovid, these paintings can be linked to the desire for a bucolic life of simplicity and harmony in nature.

I was awed to see the Robert Delaunay’s City of Paris, 1910-12. Delaunay famously painted the Eiffel Tower in a Cubist jumble of colors and shifting perspectives. That symbol of modernism was only a little more than 20 years old at this time. This giant canvas of Paris also has three large nudes. They are the Three Graces, just as Botticelli and Raphael had painted them. Delaunay’s vision of Paris includes the past and the present, but the nudes of the past are actually seem more central to this composition of shifting triangles, circles and planes of colors. If anything, Cubism reminds us of life’s impermanence.

Robert Delaunay, City of Paris, 1910-12, is 8’9″ x 13’4″

Finally, at the end we see

Franz Marc’s Deer in Forest, II, from the Phillips Collection. Here the humans are gone and only animals are in the forest. The exhibition is very thoughtful and reflective, and I thank Curator Joseph Rishel for giving us so much to ponder. It is one designed not only to make us only look art more closely, but we must also think more deeply.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 5, 2011 | 19th Century Art, Exhibition Reviews, Gauguin, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, National Gallery of Art Washington, The Art Institute of Chicago

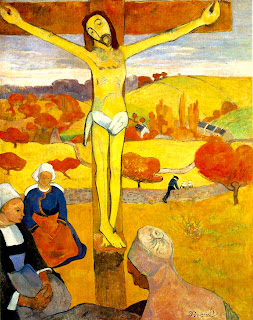

Paul Gauguin was impressed with the sincere, unspoiled piety of women from Brittany, where he painted in 1887. He placed the Yellow Christ, 1889, in a Breton landscape.

Paul Gauguin was impressed with the sincere, unspoiled piety of women from Brittany, where he painted in 1887. He placed the Yellow Christ, 1889, in a Breton landscape.

Paul Gauguin, an early modern rebel against western culture, is influenced by religious culture like his French forebears who painted for kings and churches 400 years earlier. After seeing the Art Institute of Chicago’s exhibition of

Early Renaissance Art in France, I saw the Gauguin exhibition at the National Gallery. Many of Gauguin’s subjects also had religious themes. He put the Crucifixion in a setting of yellow and ocher pigments, and blended it into the landscape of Brittany, a region he respected for its piety and cultural backwardness at that time.

The standing woman in Delectable Waters, above, has the shame of Eve being expelled from the garden of Paradise. We don’t know her relationship to the other women, although they also seem to live in a lush tropical place, much like a Garden of Eden

The standing woman in Delectable Waters, above, has the shame of Eve being expelled from the garden of Paradise. We don’t know her relationship to the other women, although they also seem to live in a lush tropical place, much like a Garden of Eden

Many of the paintings in Gauguin: Maker of Myth come from his Tahitian stay after 1891. He treats several scenes of Tahitian women and gods through the lens of Christianity and other religious traditions. It’s curious that the moon goddess Hina who appears in Delectable Waters, above, is actually in a pose from Hinduism that Gauguin morphs into this Tahitian image. In some canvases the Tahitian women, rather than Eve, deal with evil and temptation. He portrays human dramas of guilt, fear, agony and pain.

Why Are You Angry, from the Art Institute of Chicago, has always fascinated me. It also seems to have a mysterious theme of guilt or shame. This encounter between a standing lady and two seated girls who humble themselves creates a provocative drama separated by an old woman and a tree. Each woman is strongly modeled with lovely, brownish skin tones. The colors of this paradise blend warm hues of yellow and red with the cool, peaceful colors of mauve and blue.

Why Are You Angry, from the Art Institute of Chicago, exemplifies Gauguin’s ability to balance the warm and cool colors of nature, while the composition is balancing the various sides of the human drama .

Even before going to Tahiti, he painted of Christ’s

Agony in the Garden, showing Jesus is a human who feels the same pain of rejection that we, as humans, do. He uses his own face as Jesus Christ. Bright red-orange hair is symbolic of the fire and pain of human suffering, which we see not only as Jesus but part of humankind. There are many self-portraits on view

. Symbolist Self-Portrait from the National Gallery’s collection, shows the paradox of his own good and evil natures, making his choices appear like Adam and Eve’s. More powerful than ego promotion, these self-portraits are powerful expressions of the human dilemma. After all, he started out as a stockbroker, which clearly did not work for him. The exhibition has an impressive display of Gauguin’s sculpture and ceramics, even in self-portraiture.

The Agony in the Garden, is a Christian theme. Here Gauguin has given Jesus his own face, suggesting that he empathized and identified with the suffering of Jesus.

The Agony in the Garden, is a Christian theme. Here Gauguin has given Jesus his own face, suggesting that he empathized and identified with the suffering of Jesus.

One can wonder if Gauguin ever overcame his pain, shame and reached a type of salvation in his final destination, Tahiti. Whether it was Eden, Tahiti or Gethsemane, he seems to paint so many gardens, the paradises for which he hoped. (He had spent a childhood in Peru, traveled to the island of Martinique, to the opposite corners of France, Brittany and Arles, in search of simplicity before arriving in the South Seas.) Curiously, there are no paintings representing his short stay in Arles with Vincent Van Gogh.

In the end, Gauguin leaves his meanings ambiguous, but color is Gauguin’s salvation as an artist.

Two Women, above, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, shows Gauguin’s gift of color–not only yellow sky and brilliant red cherries. The woman to the right is painted with green hues beneath her brown skin, a wonderful match for her blue dress, while the other women has red under brown skin.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments