by Julie Schauer | Feb 13, 2016 | Ceramics, Contemporary Art, Eva Zeisel, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Industrial Design, Isamu Noguchi, Karen Karnes, National Museum for Women in the Arts, Ruth Asawa, Surrealism

|

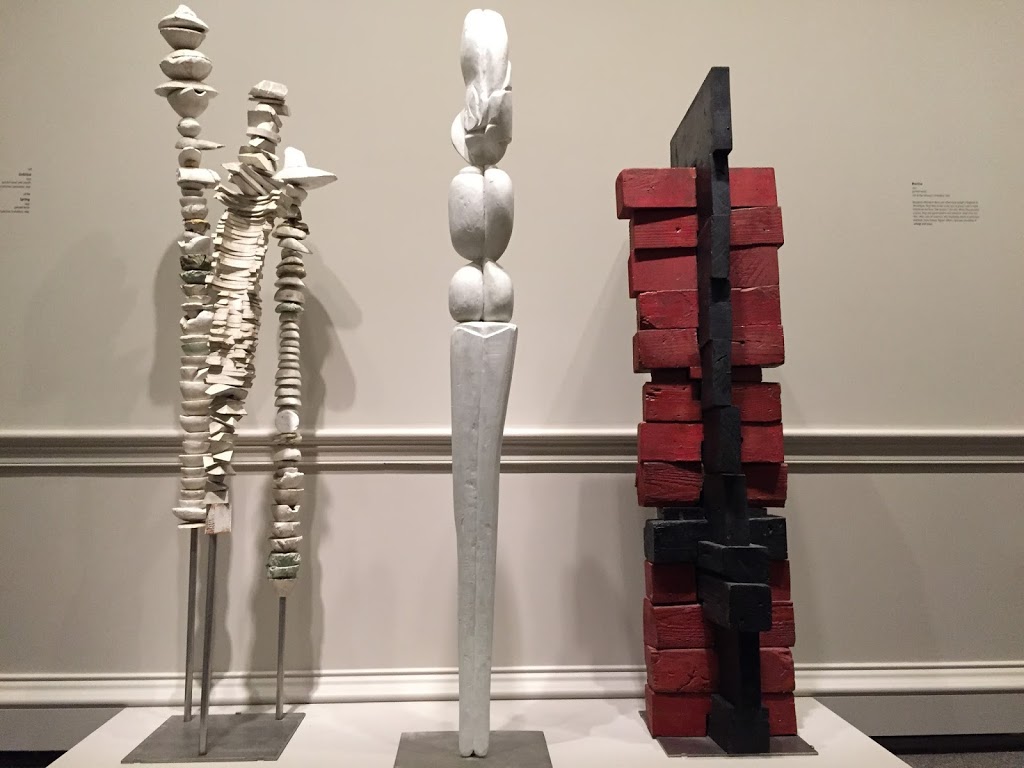

Isamu Noguchi, Trinity, 1945, Gregory, 1948, Strange Bird (To the Sunflower)

Photo taken from the Hirshhorn’s Facebook page |

Biomorphic and anthropomorphic themes run through quite a few exhibitions of modern artists in Washington at the moment. The Hirshhorn’s Marvelous Objects: Surrealist Sculpture from Paris to New York has several of the abstract, biomorphic Surrealists such as Miro and Calder. The wonderful exhibition will come to a close after this weekend.

Isamu Noguchi’s many sculptures that are part of Marvelous Objects deal with an unexpected part of the artist’s life and work. Noguchi was interned in a prison camp in Arizona for Japanese-Americans during World War II. Whatever the horrors of his experience, he dealt with it as an artist does — making art and using creativity to express the experience by transforming it.

|

| Isamu Noguchi, Lunar Landscape, 1944 |

Lunar landscape comes from immediately after this difficult time period. The artist explained, “The memory of Arizona was like that of the moon… a moonscape of the mind…Not given the actual space of freedom, one makes its equivalent — an illusion within the confines of a room or a box — where imagination may roam, to the further limits of possibility and to the moon and beyond.” It’s like taking tragedy and turning it into magic.

|

| Strange Bird (To the Sunflower), 1945 Noguchi Museum, NY |

|

|

The most interesting piece from this period is Strange Bird (To the Sunflower), 1945. It is pictured here 2x — on top photo, right side, and from a different angle on the left, from a photo in the Noguchi Museum. Between 1945 and 1948, Noguchi made a series of fantastic hybrid creatures that he called memories of humanity “transfigurative archetypes and magical distillations.” Yet the simplicity and the Zen quality I expect to see in his work is gone from this time of his life.

From the beginning of time, “humans have wanted a unifying vision by which to see the chaos of our world. Artists fulfill this role,” said Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto.

I’m reminded of the ancient Greeks who created satyrs and centaurs to deal with their animal nature. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there’s a small Greek sculpture of a man and centaur from about 750 BCE, the Geometric period. The man confronting the centaur seems to be taming him or subduing his own animal nature. Like Noguchi’s sculpture, it has hybrid forms and angularity, but it’s made of bronze. Noguchi’s sculpture is of smooth green slate, which gives it much of its beauty and polish.

|

| Man and Centaur, bronze, 4-3/4″ mid-8th century BCE Metropolitan Museum |

Noguchi was a landscape architect as well as a sculptor. When designing gardens, he rarely used sculpture other than his own. Yet he bought garden seats by ceramicist Karen Karnes. A pair of these benches by Karnes are now on display at the National Museum for Women in the Arts’ exhibition of design visionaries. Looking closely, one sees how she used flattened, hand-rolled coils of clay to build her chairs. The craftsmanship is superb. It’s easy to see how her aesthetic fit into Noguchi’s refined vision of nature.

|

| Karen Karnes, Garden seats, ceramic, from the Museum of Arts in Design, now at NMWA |

|

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 10, 2016 | 20th Century Art, Constantin Brancusi, Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi, Louise Bourgeois, Sculpture, Surrealism

“Contemporary and ancient art are like oil and water, seemingly opposite poles….now I have found the two melding ineffably into one, more like water and air.” Hiroshi Sugimoto, Japanese artist

|

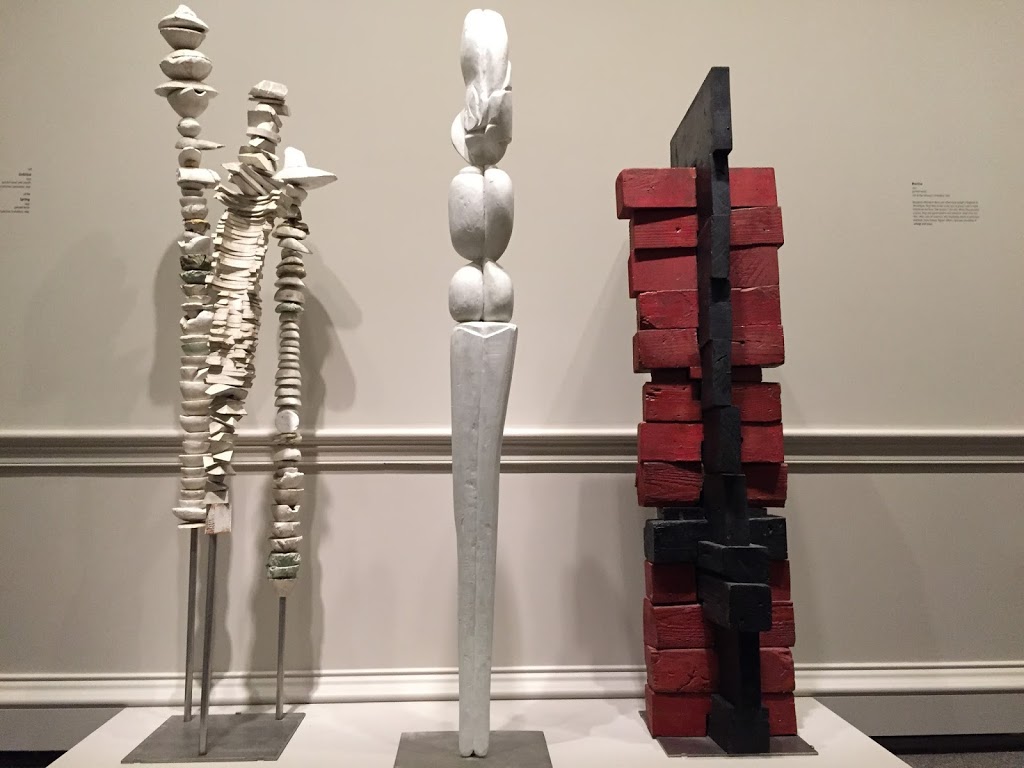

| Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1952, Spring, 1949 and Mortise, 1950 National Gallery of Art |

|

|

Two separate exhibitions in Washington at the moment illustrate the commonality of modern art and prehistoric — especially in sculpture. The me, that theme resonates with two sculptors who lived through most of the 20th century, Louise bourgeois and Isamu Noguchi. The National Gallery has a two-room exhibition Louise Bourgeois:No Exit, and Noguchi (hopefully in another blog)‘s works are part of the Hirshhorn’s exhibition, Marvelous Objects: Surrealist Sculpture from Paris to New York.

|

Constantin Brancusi, Endless Column,1937

|

|

|

Three sculptures by Bourgeois in the National Gallery are what she called personages. As a whole they’re not unlike the archetypal images of Henry Moore or Constantin Brancusi. Among these three works are a group of three piles of stones resting on stilts. It’s one of the Bourgeois sculptures that

|

Barbara Hepworth, Figure in Landscape,cast 1965

|

appears simple and somewhat primitive. Untitled is above on the left. The stones stand tall and top heavy; they seem to be wearing big hats. I’m reminded of the precarious state of human existence. I am also thinking of the top-heavy candidates in the recent Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary, weak on bottom and they may fall. Aesthetically these works form a link to Brancusi’s birds on pedestals and the Endless Column, Targu Jui, Romania, part of a memorial for fallen soldiers in World War I.

The sculpture of Spring center above is reminiscent of a woman, or of the ancient Venus figures, which date to the Paleolithic era, around 20,000 BCE. It can be compared the the elongated marble burial figures from prehistoric, Cycladic Greece as well.

|

| “Venus” figures from Dolni Vestinici, Willendorf, Austria and Lespuge, France |

|

|

|

A version of Alberto Giacometti’s bronze Spoon Woman from the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas is in the surrealist exhibition (Example below from Art Institute of Chicago). Giacometti made this archetypal image in 1926/27, but the bronze was cast in 1954. Henry Moore’s Interior and Exterior Forms, is a theme he did over and over, is an archetype of the mother and child.

|

| Giacometti, Spoon Woman, 1926/27, cast |

1954 |

In 1967, the Museum Ludwig, founded by chocolate manufacturers in Cologne, Germany, asked for one of her sculptures to be replicated in a single large piece of chocolate. She chose Germinal, its name suggestive of germination and new beginnings. (Germinal is also the name of Emile Zola’s famous French novel of 19th century coal minors. I wouldn’t put it past her to be referring to the story, but don’t have an idea as to how and why)

|

| Germinal, 1967, promised gift of Dian Woodner, copyright |

|

|

Bourgeois, who died in 2010, lived to be 98 years. She continually worked and invented anew. In time, I think she will be considered a giant among the sculptors of the 20th century, on par with Moore, Brancusi and Calder. Her art was more varied than the others and she defied categorization and/or predictability. However, certain themes seemed to carry her for long periods of time, such as the personages of her early to middle period and the cells she did late in her life. She worked both vary large and very small and with an infinite variety of materials including fiber. She grew up in a family which worked in the tapestry business, primarily repairing antique tapestries. To her, making art was making reparations making peace with the past. Some wish to put her in the category of Surrealism, but she calls herself an Existentialist, in the philosophical realm of Jean-Paul Sartre. Looking at some of the drawings in the National Gallery and how she explained it does give a clue into the existential thoughts and feelings.

|

| Spider, 2003 (not in exhibition) |

One of Bourgeois’s best-known themes was the spider, having done several monumental statues in public places. The spider stands for the protective mother, and her version of the archetype, as it also alludes to the weaving activity in her family. It is large and embracing but can also have a dark side. I like best the spiders that combine the metal sculpture with the delicate tapestry figures. The delicacy and litheness of her spider people remind me of the wonderful organic acrobat sculptures from ancient Crete.

|

| Bull-leaping acrobat, ivory, from Palace at Knossos, Crete, c. 1500 BCE |

Bourgeois deals with metaphors. She calls sculpture the architecture of memory. She is poetic, but she’s also quite humorous. She also made a sculpture series of giant eyes. She describes eyes mirrors reflecting various realities. I’m reminded that in ancient times, the eyes were the mirrors of a person’s soul. As different as her works may be, she portrays a consistent voice and aesthetic throughout her career.

|

| Eye Bench, 1996-97, Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle |

When I went to the Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle back in 2010, a friend of mine from California and I came upon her Eye Benches. We sat down and enjoyed it. She designed three different sets of eye benches made of granite. In the end, it seems Bourgeois used her art to make sense of her very complicated world and our experience of that world. Sometimes she seems to laugh at it all, so this experience calls for a good laugh and relaxation.

|

| Louise Bourgeois, Eye Bench, Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle. |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments