by Julie Schauer | Feb 13, 2016 | Ceramics, Contemporary Art, Eva Zeisel, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Industrial Design, Isamu Noguchi, Karen Karnes, National Museum for Women in the Arts, Ruth Asawa, Surrealism

|

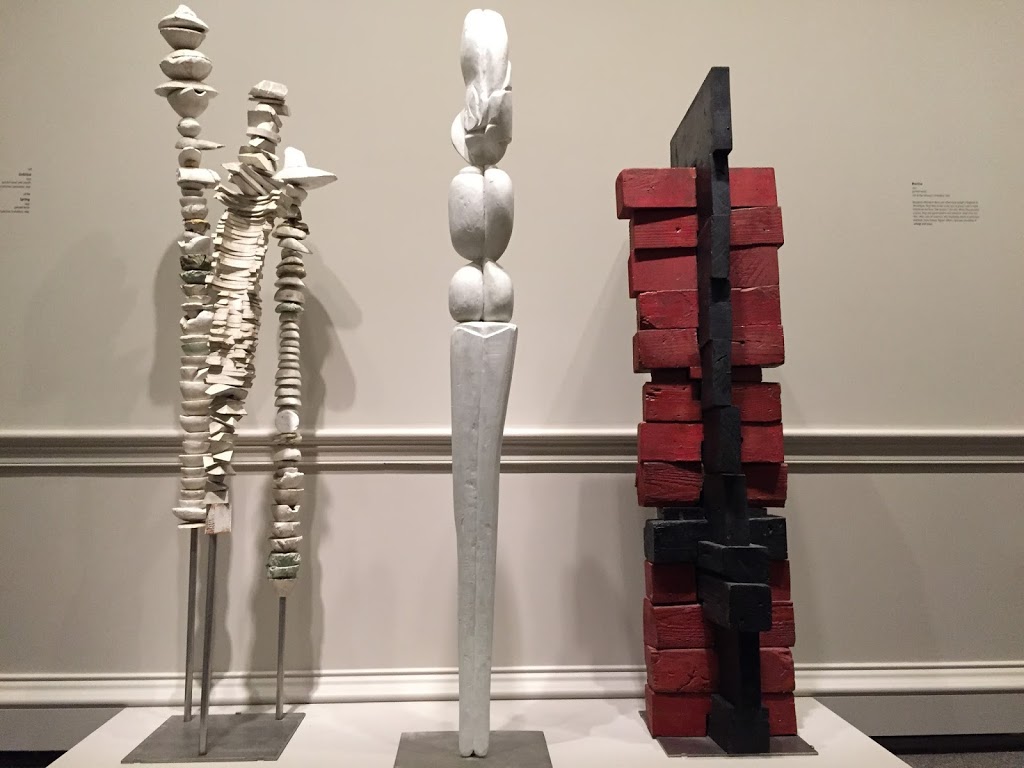

Isamu Noguchi, Trinity, 1945, Gregory, 1948, Strange Bird (To the Sunflower)

Photo taken from the Hirshhorn’s Facebook page |

Biomorphic and anthropomorphic themes run through quite a few exhibitions of modern artists in Washington at the moment. The Hirshhorn’s Marvelous Objects: Surrealist Sculpture from Paris to New York has several of the abstract, biomorphic Surrealists such as Miro and Calder. The wonderful exhibition will come to a close after this weekend.

Isamu Noguchi’s many sculptures that are part of Marvelous Objects deal with an unexpected part of the artist’s life and work. Noguchi was interned in a prison camp in Arizona for Japanese-Americans during World War II. Whatever the horrors of his experience, he dealt with it as an artist does — making art and using creativity to express the experience by transforming it.

|

| Isamu Noguchi, Lunar Landscape, 1944 |

Lunar landscape comes from immediately after this difficult time period. The artist explained, “The memory of Arizona was like that of the moon… a moonscape of the mind…Not given the actual space of freedom, one makes its equivalent — an illusion within the confines of a room or a box — where imagination may roam, to the further limits of possibility and to the moon and beyond.” It’s like taking tragedy and turning it into magic.

|

| Strange Bird (To the Sunflower), 1945 Noguchi Museum, NY |

|

|

The most interesting piece from this period is Strange Bird (To the Sunflower), 1945. It is pictured here 2x — on top photo, right side, and from a different angle on the left, from a photo in the Noguchi Museum. Between 1945 and 1948, Noguchi made a series of fantastic hybrid creatures that he called memories of humanity “transfigurative archetypes and magical distillations.” Yet the simplicity and the Zen quality I expect to see in his work is gone from this time of his life.

From the beginning of time, “humans have wanted a unifying vision by which to see the chaos of our world. Artists fulfill this role,” said Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto.

I’m reminded of the ancient Greeks who created satyrs and centaurs to deal with their animal nature. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there’s a small Greek sculpture of a man and centaur from about 750 BCE, the Geometric period. The man confronting the centaur seems to be taming him or subduing his own animal nature. Like Noguchi’s sculpture, it has hybrid forms and angularity, but it’s made of bronze. Noguchi’s sculpture is of smooth green slate, which gives it much of its beauty and polish.

|

| Man and Centaur, bronze, 4-3/4″ mid-8th century BCE Metropolitan Museum |

Noguchi was a landscape architect as well as a sculptor. When designing gardens, he rarely used sculpture other than his own. Yet he bought garden seats by ceramicist Karen Karnes. A pair of these benches by Karnes are now on display at the National Museum for Women in the Arts’ exhibition of design visionaries. Looking closely, one sees how she used flattened, hand-rolled coils of clay to build her chairs. The craftsmanship is superb. It’s easy to see how her aesthetic fit into Noguchi’s refined vision of nature.

|

| Karen Karnes, Garden seats, ceramic, from the Museum of Arts in Design, now at NMWA |

|

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 10, 2016 | 20th Century Art, Constantin Brancusi, Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi, Louise Bourgeois, Sculpture, Surrealism

“Contemporary and ancient art are like oil and water, seemingly opposite poles….now I have found the two melding ineffably into one, more like water and air.” Hiroshi Sugimoto, Japanese artist

|

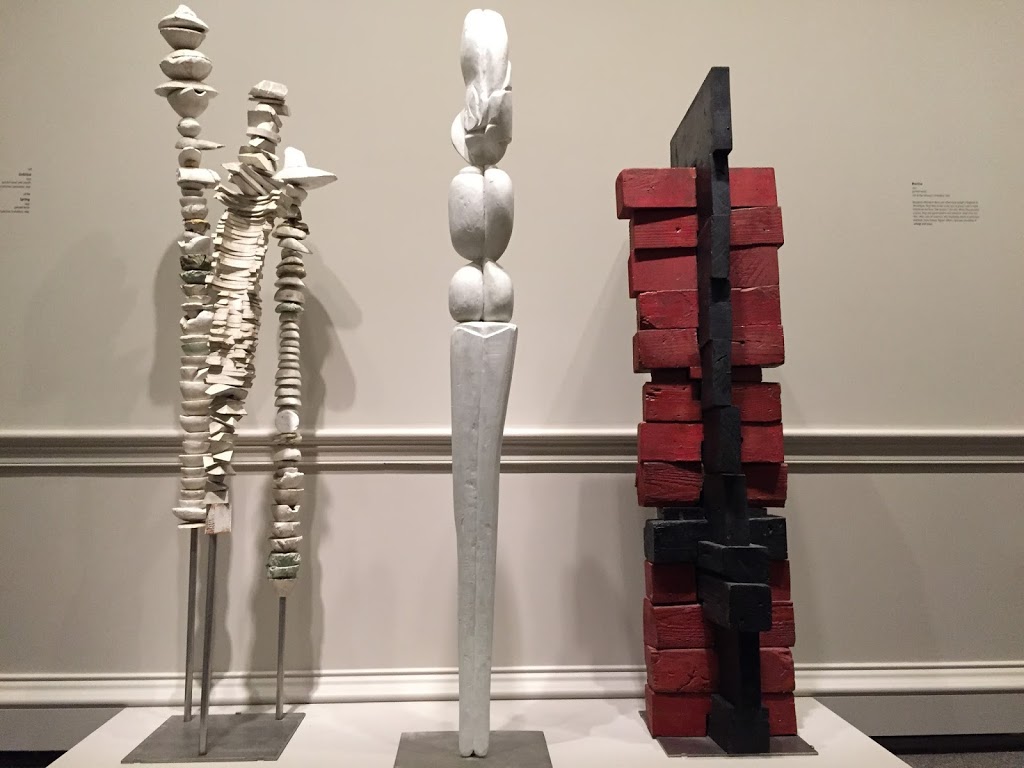

| Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1952, Spring, 1949 and Mortise, 1950 National Gallery of Art |

|

|

Two separate exhibitions in Washington at the moment illustrate the commonality of modern art and prehistoric — especially in sculpture. The me, that theme resonates with two sculptors who lived through most of the 20th century, Louise bourgeois and Isamu Noguchi. The National Gallery has a two-room exhibition Louise Bourgeois:No Exit, and Noguchi (hopefully in another blog)‘s works are part of the Hirshhorn’s exhibition, Marvelous Objects: Surrealist Sculpture from Paris to New York.

|

Constantin Brancusi, Endless Column,1937

|

|

|

Three sculptures by Bourgeois in the National Gallery are what she called personages. As a whole they’re not unlike the archetypal images of Henry Moore or Constantin Brancusi. Among these three works are a group of three piles of stones resting on stilts. It’s one of the Bourgeois sculptures that

|

Barbara Hepworth, Figure in Landscape,cast 1965

|

appears simple and somewhat primitive. Untitled is above on the left. The stones stand tall and top heavy; they seem to be wearing big hats. I’m reminded of the precarious state of human existence. I am also thinking of the top-heavy candidates in the recent Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary, weak on bottom and they may fall. Aesthetically these works form a link to Brancusi’s birds on pedestals and the Endless Column, Targu Jui, Romania, part of a memorial for fallen soldiers in World War I.

The sculpture of Spring center above is reminiscent of a woman, or of the ancient Venus figures, which date to the Paleolithic era, around 20,000 BCE. It can be compared the the elongated marble burial figures from prehistoric, Cycladic Greece as well.

|

| “Venus” figures from Dolni Vestinici, Willendorf, Austria and Lespuge, France |

|

|

|

A version of Alberto Giacometti’s bronze Spoon Woman from the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas is in the surrealist exhibition (Example below from Art Institute of Chicago). Giacometti made this archetypal image in 1926/27, but the bronze was cast in 1954. Henry Moore’s Interior and Exterior Forms, is a theme he did over and over, is an archetype of the mother and child.

|

| Giacometti, Spoon Woman, 1926/27, cast |

1954 |

In 1967, the Museum Ludwig, founded by chocolate manufacturers in Cologne, Germany, asked for one of her sculptures to be replicated in a single large piece of chocolate. She chose Germinal, its name suggestive of germination and new beginnings. (Germinal is also the name of Emile Zola’s famous French novel of 19th century coal minors. I wouldn’t put it past her to be referring to the story, but don’t have an idea as to how and why)

|

| Germinal, 1967, promised gift of Dian Woodner, copyright |

|

|

Bourgeois, who died in 2010, lived to be 98 years. She continually worked and invented anew. In time, I think she will be considered a giant among the sculptors of the 20th century, on par with Moore, Brancusi and Calder. Her art was more varied than the others and she defied categorization and/or predictability. However, certain themes seemed to carry her for long periods of time, such as the personages of her early to middle period and the cells she did late in her life. She worked both vary large and very small and with an infinite variety of materials including fiber. She grew up in a family which worked in the tapestry business, primarily repairing antique tapestries. To her, making art was making reparations making peace with the past. Some wish to put her in the category of Surrealism, but she calls herself an Existentialist, in the philosophical realm of Jean-Paul Sartre. Looking at some of the drawings in the National Gallery and how she explained it does give a clue into the existential thoughts and feelings.

|

| Spider, 2003 (not in exhibition) |

One of Bourgeois’s best-known themes was the spider, having done several monumental statues in public places. The spider stands for the protective mother, and her version of the archetype, as it also alludes to the weaving activity in her family. It is large and embracing but can also have a dark side. I like best the spiders that combine the metal sculpture with the delicate tapestry figures. The delicacy and litheness of her spider people remind me of the wonderful organic acrobat sculptures from ancient Crete.

|

| Bull-leaping acrobat, ivory, from Palace at Knossos, Crete, c. 1500 BCE |

Bourgeois deals with metaphors. She calls sculpture the architecture of memory. She is poetic, but she’s also quite humorous. She also made a sculpture series of giant eyes. She describes eyes mirrors reflecting various realities. I’m reminded that in ancient times, the eyes were the mirrors of a person’s soul. As different as her works may be, she portrays a consistent voice and aesthetic throughout her career.

|

| Eye Bench, 1996-97, Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle |

When I went to the Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle back in 2010, a friend of mine from California and I came upon her Eye Benches. We sat down and enjoyed it. She designed three different sets of eye benches made of granite. In the end, it seems Bourgeois used her art to make sense of her very complicated world and our experience of that world. Sometimes she seems to laugh at it all, so this experience calls for a good laugh and relaxation.

|

| Louise Bourgeois, Eye Bench, Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle. |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Aug 1, 2012 | Mexican Art, Modern Art, Surrealism, Women Artists

Since going to the Miró exhibition recently, I’ve been reminded of Remedios Varo. In 2000, I discovered this marvelous Surrealist in an exhibition devoted to her at Chicago’s Mexican Fine Arts Museum. Called The Magic or Remedios Varo, the exhibition had been organized by Washington’s National Museum of Women in the Arts and shown there. At the moment of this writing there is an exhibition at Mexico City’s Museo de Arte Moderne de Mexico, entitled Remedios Varo: 50 Keys. It includes 50 works of art and a single sculpture.

Certainly Frida Kahlo is much better known, but I find Varo, who knew both Kahlo and Diego Rivera, more evocative and interesting as an artist. Varo also uses a female subject as her chief descriptive vehicle, but she is less self-absorbed than Kahlo and more concerned with the larger world.

Varo was a Surrealist born in Spain in 1908, but exiled to Mexico after 1941. Like Gaudi, Miró and Dalí, she was Catalan, originally from Angles, near Girona and close to the French border. Some of the literature I read of her suggested she was a scientist with a dedication to nature close to that of Leonardo da Vinci. She learned much through her father, an engineer, and lived part of her childhood in Morocco. Varo is certainly a detail artist and paints more in the style of a tempera painter than an oil painter. Yet I hardly see a deep devotion to science; her art taps into more of a spiritual quest for understanding the world. Perhaps, to other observers, she bridges the gap between science and the mystical.

Varo’s people are tall and thin, elongated like Sienese or Catalan figures from around 1400. Her perspective is also similar, somewhat long and exaggerated, also. She has a delicate touch and is able to find connections unexpectedly. As a woman spins in The Alchemist, above, the checkerboard of her cloak turns into tile patten of the floor beneath her. Or is it opposite? She could be weaving the tile floor into her clothing. Some kind of contraption behind her is the machinery that connecting what’s inside with the outdoors. The perspective is like Sienese artist Giovanni di Paolo.

Throughout her work I’m reminded of creativity, where it comes from and where it goes. Her artwork evokes these connections again and again. There something mystical in how it comes about. While The Flutist, above, plays next to a mountain, the stones magically rise and form a tower, while a schematic mathematical drawing holds the tower in place. Stairs of the tower are rising, going up to heaven like a Tower of Babel. However, some sources cite the the periodic table of chemistry, though I don’t quite see that connection. There are fossils on these stones, so a connection to the ancient past, present and future come together in one place.

Creation of the Birds, left, dates to 1957. As a wise woman in owl’s clothing paints birds, the birds fly out the window, She also holds a magnifying glass lit by a star out the window which, in turn, illuminates her creation. The brush comes out in her center, the heart source of creativity, which is really a guitar strung around her neck. There are egg-shaped contraptions on the floor and out another window. In fact, this machine mixes her paint, while a bird eats on the floor. Art, music, inspiration, heart, mind, and inspiration flow together, while birds fly in and out. The artist’s work is to connect inner and outer worlds.

Varo’s connection to Surrealists in Paris and Barcelona was strong. She attended the Academy of San Fernando in Madrid, the same art school as Salvador Dalí had attended. We know little of her work in Europe before she went to Mexico, but we know she admired the paintings of Heironymous Bosch at the Prado and philosophical writings of the hermetic tradition. Most of the work that can be seen is comes from the 1950s up to her death in 1963. Her association with the Surrealism made her unacceptable to either the Spanish government after the Civil War or a France during Nazi occupation. She and her French husband fled to Mexico where they met other artists such as English-born Leonora Carrington, perhaps the artist closest to her in style.

We can’t always know what was on her mind, as in the case of much Surrealism, but there seems to be a desire to tap into the origin of creativity and to connect the self (herself) to the larger universe. Her last painting, before she unexpectedly died of a heart attack at age 53, was Revolving Still Life. Pieces of fruit spin off plates as the planets orbit the sun. How interesting the many ways she can connect the small and ordinary with the big, cosmic implications! She has many online followers and fans of her work. There was an exhibition in Los Angeles last Spring which featured 10 of her paintings.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Jul 24, 2012 | Art Appreciation: Visual Analysis, Exhibition Reviews, Joan Miro, Modern Art, National Gallery of Art Washington, Surrealism

|

Joan Miró, Nocturne, 1935, is a small oil on copper

from the Cleveland Museum of Art. A jumping man,

crescent moon and spiral suggest the artist ability to

leap above problems of life. |

“We Catalans believe you must always plant your feet firmly on the ground if you want to be able to jump into the air”

In 1948, Joan Miró used these words to describe the Catalan mentality. Like Salvador Dali and Antoni Gaudí, giants of modern art and architecture, Miro came from Catalonia, the area of Spain on the Mediterranean Sea near the French border. Catalans had a language and cultural identify different from the rest of Spain. Washington’s National Gallery, which hosts a Miro exhibition until August 12, completes the quote on a wall label:

“The that I came down to earth from time to time makes it possible for me to jump higher.”

Joan Miró: Ladders of Escape is the appropriate name for this exhibition which captures the flying spirit of this Surrealist artist. From beginning to end, the exhibit relates him the times and places he lived. His lifespan was long, from 1893 until 1983. As the world changed so much during the the 20th century, politically, artistically and technologically, his art also changed but kept some continuities.

|

Vegetable Garden and Donkey, Moderna Museet, Stockholm,

1918, reveals Miro’s roots |

Miró’s family had a farm in the country town called Montruig, “red mount” in Catalan. The earliest paintings show his roots in an agricultural land which launched him. Some of the animals, particularly the rooster, will recur in his art, after he moved to Paris in 1920.

The National Gallery of Art’s large painting called The Farm, 1921-23, in a style at times called detailism, shows a compulsive need to fill up the painting. Miro considered it autobiographical and Ernest Hemingway, who owned it, thought it represented both the artist and Spain in the midst of change. Meticulous and precise, The Farm has two ladders, 4 rabbits, 2 roosters, other birds and crops, buildings and a tree in the center. There is “earthiness” on the ground, but the animals are perched on top of various launching pads; In this painting, we witness a Miró who is ready take off as an artist.

|

| By the time Miró painted the National Gallery’s The Farm, 1921-23, his art began to change. Shown above is a detail of the painting has farm animals and other symbols such as the ladder which will remain most of his life. |

in 1923, he joined the Surrealist group of artists led by André Breton. He adopted a biomorphic Surrealism which is more abstract than realistic. He began to use repetitious motifs, such as a “Catalan Peasant,” ladders, roosters. Surrealism put the subconscious mind on equal par with the conscious mind and Miró’s images appear as symbols. A painting of 1926, Dog Barking at the Moon, gives insight into Miró’s thinking. If the barking dog is chasing the moon, his dreams, the ladder suggests a way to get there.

|

Joan Miro, Dog Barking at the Moon, 1926, is from the Philadelphia

Museum of Art is an early example of his Surrealism. |

During this time in Paris, Miró was working with free association. He even said, “Rather than setting out to paint something, I begin painting………and the paint begins to assert itself.” In style and in working methods, we can also associate him with Antoni Gaudí, who was constantly revising and changing his drawings for the Sagrada Familia as he worked. The ladders of Miró are like the towers of Gaudí, leaping points into an imagined world. The ability to escape proved to be a good tool to use in hard times.

The state of affairs surrounding Miró got worse. The economy in Europe became very difficult and Miro returned home to Catalonia, to the city of Barcelona. Peace in Spain was shorl-lived; the Depression hit in 1932 and in 1934, the Catalan Republic was suppressed. In 1936, The Spanish Civil War began and lasted until 1939. Still Life with an Old Shoe, a painting from this time, has a fork going through and apple. Miró described the painting as having a “realism that is far from photographic.”

|

Still Life with Old Shoe, 1936 is in MoMA’s Collection. Miró managed to find

color in the depressing conditions of the Spanish Civil War. |

|

Morningstar, 1941, is the in the Fundació Miró of Barcelona,

one of two European museums which has hosted the exhibition. |

By 1933, Miró grew apart from the Surrealists, as he did not support Communism, and they did not respect him working with popular art and designing tapestries. During the Spanish Civil War, he did a series of dark paintings and, like Picasso, did a piece for the Spanish Republican Pavilion in the 1937 Paris exhibition (

The Reaper was political, but is not in this show.) When Franco triumphed in Spain’s Civil War (with the help of Hitler and Mussolini), Miró did not support his regime. He went back to Paris briefly, but the Nazis would soon invade Paris and he left again. During his self-imposed exile to Normandy and the Spanish island of Majorca, he did a “Constellation” series of gouaches, combining black lines with solid colored shapes. Stars, towers, and human forms dance in patterns of optimism expressing his hope in dreary times. Miró’s vivid color and organic forms solidify his artistic identity. Each painting has a star as he visualizes a dream for something better, but the work is still grounded, and never “flighty.”

|

| Message to My Friend, 1964, is in the Tate Modern Museum. |

|

|

|

|

The late paintings of Miró get even simpler and more symbolic, for example, Message to My Friend, 1964. Since the 1920s, he had been a friend of American artist Alexander Calder who had developed the mobile as an art form. Washington’s Phillips Collection in held an exhibition to highlight the artistic connection between these artists about 7 years ago. As the curator explained, they shared an incredible ability to compose line in space. (Calder’s playful circus figures remind me of the Constellation series.)

I am thankful the curators of this exhibition presented a consistent view of an artist who is able to fly and dream in the face of a pessimistic world. The exhibition does not include some of his most famous paintings, such as Harlequin’s Carnival, which would not fit into the theme. Of all the “automatic” and playful artists of the Dada and Surrealist eras, Paul Klee is my favorite because he remains truest to an automatic, childlike, form of communicating in his art. However, Miró also draws upon an honest, open and ingenuous vision. Perhaps some of his ability to look for greater heights was shown to him by an older and endlessly imaginative countryman, Antoni Gaudi. Joan Miro: Ladders of Escape will be at the Gallery until August 12th. It has already traveled through Europe, starting at the Tate in London and the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Sep 17, 2010 | Arcimboldo, Renaissance Art, Surrealism

I have often thought the Mannerist style of late Renaissance art had a lot in common with the Surrealism of the 20th century. After viewing the National Gallery’s Arcimboldo exhibition, this analogy seems stronger. Arcimboldo was a Mannerist from Milan who worked for the Court of Maximilian II in Vienna, and for his son, Rudolf II, in Vienna and in Prague. It is interesting that his reputation went down for a number of years until the Surrealists of the 20th Century revived the interest in his art.

“Librarian,” 1566, could easily be mistaken for an early 20th century Surrealist painting, at first glance. Arcimboldo painted various professions. “The Jurist,” also on display at the National Gallery, is a scathing portrayal of the legal profession.

Mannerism came after the High Renaissance style of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael, which had lasted only about 20 years. The idealism of their style seemed to perish as Europe descended into the wars and devastation that occurred after the Reformation began. Much of life may have seemed surreal, or like a very bad dream. In the same vein, Dadaism and Surrealism resulted from the irrationality of World War I, when a Europe that had supposedly reached a high level of civilization was torn asunder by senseless war.

Arcimboldo, the keen observer of nature, introduces the still life, a new genre

Arcimboldo, the keen observer of nature, introduces the still life, a new genre

of painting. His vegetable harvest is bountiful BUT……

Mannerist artists enjoyed clever, disguised subjects. Surrealists loved to play tricks, too, often playing pranks on each other.

Arcimboldo was every bit the jokester. The Vegetable Gardener, above and below, is full of onions, carrots, mushrooms, etc., but it can be turned over. (The National Gallery uses mirrors to show the reversal. )

“The Vegetable Gardener” is one of three reversible food images in

“The Vegetable Gardener” is one of three reversible food images in

the exhibition which uses mirrors to show the illusion.

In Arcimboldo’s world, plants, flowers and fruits metamorphose into human heads. Also there are lizards, bats and hideous creatures that make up human beings. While Surrealism had the goal to make the subconscious visible, Mannerism may have been doing much the same, accidentally, or subconsciously, but four centuries earlier.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments