by Julie Schauer | Mar 24, 2014 | African-American Art, American Art, Christianity and the Church, Smithsonian American Art Museum

|

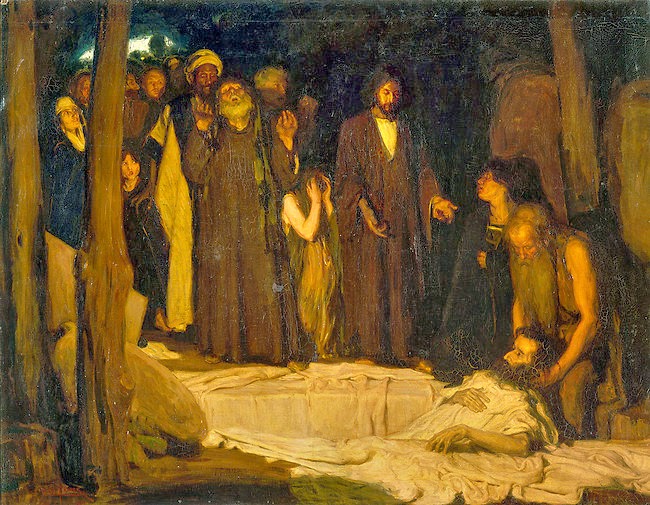

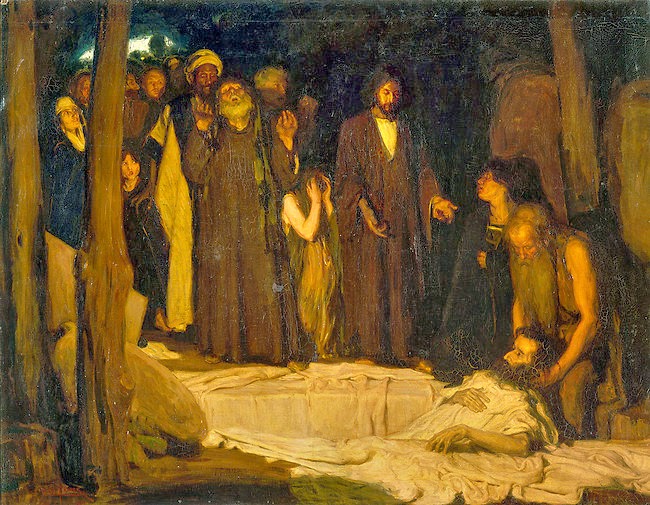

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Raising of Lazarus, Musee d’Orsay, Paris, 1896 |

Henry Ossawa Tanner, the most important African-American painter born in the 19th century, should probably be considered America’s greatest religious painter, too. He came into the world in when our country was on the brink of its Civil War, in Pittsburgh, 1859. Though his paintings are profound, he normally doesn’t get as much recognition as he deserves.

Religious painting has never been a significant genre in the United States. Mainly, it has been used for book illustration and in churches with stained glass windows. Of course, Europe had its own rich tradition of paintings for Catholic Churches and even in the Protestant Netherlands, Rembrandt made paintings and prints of biblical subjects for their religious significance.

Tanner reinvented religious painting with highly original interpretations. His father was a minister in the AME Church who ultimately became the bishop of Philadelphia in 1888. His mother was born in slavery, but escaped on the underground railway. Although Tanner was born free, he obviously experienced turbulent times and discrimination; faith could have given him solace.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Annunciation, 1894, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts |

In 1894, Tanner painted Mary, mother of Jesus, at the Annunciation, the biblical story of an angel announcing to Mary she is to be the mother of God. Typical Annunciation scenes put a flying angel interrupting a teenage girl in her bedroom. Tanner leaves out the angel and only a beam of light represents the divine encounter. Pictured as a young women in her bedroom, Mary reflects inward on the meaning of the light, knowing God has things in mind for her. The painting is absolutely beautiful, a show-stopper with a profound imagining of how Christ’s earthly life began. The streak of light appears as the leg of the cross as it passes through a horizontal shelf on the wall. When we notice this detail, we’re given a hint of how Jesus’ life ended, death by crucifixion.

|

| detail-The Raising of Lazarus |

Tanner’s technique uses mainly the pictorial language of realism to convey divine presence on Earth, in contrast to Abbot Handerson Thayer who used symbolic angels and winged figures in an idealized classical figural style. Another way to explain the difference is to say that Tanner painted in a vernacular language, instead of using the classical Latin language. His religious stories are without supernatural excess, but he uses light strategically to illuminate miracles.

Although born in Pittsburgh, most of his early life was in Philadelphia. He became the pupil of legendary teacher Thomas Eakins in 1879. Although Eakins considered him a star pupil, he faced racial prejudice from other students. Not receiving recognition in the United States, he set out for Europe in 1891, and received additional training at the Academe Julian in Paris. Philadelphia may have been the best place for an American to study art in the 19th century, but Paris was the best place for an artist to be. By 1895, his work was accepted in the Paris Salon. The next year he received an honorable mention at the Salon, and in 1897, his recognition was complete with The Raising of Lazarus, 1896. The success which alluded him the US came after only a few years living in France.

The Raising of Lazarus (top of this blog page, and to the right.) received a third class medal in the Paris Salon, but it also became the first painting to be bought by the nation of France and placed in a national museum. The painting tells the story of Jesus going into the grave of Lazarus to bring him back to life, with sisters Mary and Martha and a group of his stunned followers. Tanner captures in paint the earthly event as it actually could have taken place, but uses heightened light-dark contrast to illuminate the miracle.

|

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Two Disciples at the Tomb, 1906

Art Institute of Chicago, 51 x 41-7/8″ |

|

We can think of Tanner as similar to Caravaggio who introduced dramatic light – dark contrast to show that the calling to follow the Lord is a mysterious event. More importantly, we can think of Tanner like Rembrandt, who used light to convey subtle and mysterious psychological states that accompany a person undergoing a spiritual awakening, or witnessing a miracle. As in the works of both the earlier artists, the drama becomes an interior event.

In 1906, Tanner’s painting of Two Disciples at the Tomb won first prize at the Art Institute of Chicago’s 19th exhibition of American painting.. In it, Peter, the older man points to himself as if saying “Oh my God,” while the younger apostle John raises is head straining to with expectancy to see fulfillment of Jesus’ promise with the Resurrection. Light is strategically placed on the whitened necks against dark clothing, and the glow of their bony faces radiate a sudden awareness of the miraculous event of Christ’s Resurrection. They’re the faces of simple men, whose faith has saved them.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Three Marys, 1910 Fisk University, Nashville, TN 42″ x. 50″ |

The Three Marys is a particularly beautiful portrait of women as they see the light in front of Jesus’ tomb and that he has risen from the dead. The witnessing of a miracle is a profound spiritual event. Each woman has a slightly different psychological response. Like many of Rembrandt’s paintings, The Three Marys is nearly monochromatic, with blue as the primary color. He explained the intent of his paintings, “My effort has been to not only put the Biblical incident in the original setting, but at the same time give it the human touch….to try to convey to the public the reverence and elevation these subjects impart to me.” It seemed that as time went on, the blues get stronger and stronger in his paintings.

|

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson, 1893

Hampton University, Hampton, VA |

|

|

Actually Tanner’s best know paintings are The Banjo Lesson, 1893, at Hampden University and The Thankful Poor, 1894, in a private collection. He painted them on return to the United States and based them on memories from travel in North Carolina. Instead biblical stories, these paintings are scenes of everyday life. Yet they have a religious significance in their contemplative spirit and the suggestion of humility. The Banjo Lesson has two sources of light, an unseen window and an unseen fireplace or stove to the right. The glow of light shows that he was familiar with Impressionism and applied some of its diffusive, scattered light it.

Tanner traveled extensive to the Middle East and into the Islamic world. Trips to Egypt and Palestine in 1897 and 1898 may have given him inspiration for the settings in his paintings. After 1900, he developed a looser style, with more tonalism and the possibility of becoming more poetic.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, Abraham’s Oak, 1905, Smithsonian American Art Museum |

As we may expect, the city of Philadelphia has a substantial collection of his work, particularly where he studied, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The Smithsonian American Art Museum has a large collection of his works also. I particularly like Abraham’s Oak, which can be read as a pure landscape painting. Also fairly monochromatic, the painting reflects the Tonalist style prevalent in the United States at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. Tonalist landscapes are moody, evocative, contemplative and spiritual. He combines the underlying beauty in nature with a symbolic oak, the place Abraham staked out for his people as the Jewish patriarch.

Like the great early 19th century artist Eugene Delacroix, Tanner was fascinated by North African subjects and themes. (I see Delacroix’s influence in the vivid colors and the way he treated the floor patterns in The Annunciation.) He went to Algeria in 1908 and Morocco in 1912. The Atlas Mountains of Morocco are said have been inspiration a late painting, The Good Shepherd, also in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Figures became smaller, but faith is still his driving force. The unification of subject with landscape has increased. There’s a huge precipice these sheep could fall down, but their loving shepherd protects them. According to Jesse Tanner, his son, the artist believed that “God needs us to help fight with him against evil and we need God to guide us.” He lived to be 79, dying in 1937.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Good Shepherd, c. 1930 Smithsonian American Art Museum |

(I have seen only one exhibition of his paintings at the Terra Museum of American Art, back around 1996 and the work mesmerized me.) An exhibition in Philadelphia two years ago attempted to bring Tanner the recognition due to him. Here’s a professor’s review of the exhibit which also traveled to Cincinnati and to Houston.

There may be reasons apart from racism as to why he is not more famous in America. The United States lacks a tradition of religious painting and doesn’t easily embrace it. Furthermore, art historians celebrate artists who are innovators, those who bring art forward. Although Tanner was painting at the time of Picasso, Matisse, Kandinsky, Klee and O’Keeffe, he was not strongly affected by their trends of change. He stayed true to himself and in that way, he is a prophet of his faith rather than a prophet of the avant-garde.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 25, 2014 | Byzantine Art, Cathedral of Hildesheim, Christianity and the Church, Exhibition Reviews, Metalwork, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mosaics, National Gallery of Art Washington, The Middle Ages

Archangel Michael, First half 14th century tempera on wood, gold leaf

overall: 110 x 80 cm (43 5/16 x 31 1/2 in.) Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens

Gold radiates throughout dimly-lit rooms of the National Gallery of Art’s exhibition, Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Art from Greek Collections. Some 170 important works on loan from museums in Greece trace the development of Byzantine visual culture from the fourth to the 15th century. Organized by the Benaki Museum in Athens, it will be on view until March 2 and then at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles beginning April 19. The National Gallery has a done a great job organizing the show, getting across themes of both spiritual and secular life spanning more than 1000 years. The exhibition design is masterful and includes a film about four key Greek churches. The photography is exquisite and provides the full context for the Byzantine church art.

There are dining tables, coins, ivories, jewelry and other objects, but it’s the mosaics which I find most captivating, and this exhibition allows a close-up view. Their nuances of size and shape can be closely observed here, but not in slides or in the distance. Byzantine artists gradually replaced stone mosaics with glass tesserae, painting gold leaf behind the glass to portray backgrounds for the figures. It was the Byzantines created these wondrous images by transforming the Greco-Roman tradition of floor mosaics to that of wall mosaics.

|

| Van Eyck, St John the Baptist, det-Ghent Altarpiece |

|

|

New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art recently hosted another exhibition of the Middle Ages, “Treasures from Hildesheim,” works from the 10th through 13th centuries from Hildesheim Cathedral in Germany. Even though Greek Christians of Byzantine world officially split from Rome in the 11th century, the two exhibitions show that the art of east and west continued to share much in terms of iconography and style. Jan Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, from the 15th century, contains a Deesis composed of Mary, Jesus and John the Baptist, in its center, proving how persistent Byzantine iconography was in the West. That altarpiece shows the early Renaissance continuation of imagining heaven as glistening gold and jewels.

Church architecture evolved very differently however, with the Latin church preferring elongated churches with the floor plan of Roman basilicas. The ritual requirements of the Orthodox Church resulted in a more compact form using domes, squinches and half-domes. Fortunately, the National Gallery’s exhibition has a lot of information about Orthodox churches, their layout and how the Iconostasis (a screen for icons) divided the priests from the congregation.

|

| Reliquary of St. Oswald, c. 1100, is silver gilt |

Both cultures re-used works from antiquity. In the East, the statue heads of pagan goddesses could become Christian saints with a addition of a cross on their foreheads. In the west, ancient portrait busts inspired gorgeous metalwork used for the relics of saints, such as the reliquary of St. Oswald, which actually contained a portion of this 7th century English saint’s skull. Mastering anatomy, perspective and foreshortening was not as important an aim as it was to evoke the glory and golden beauty of heaven as it was imagined to be. The goldsmiths and metalsmiths were considered the best artists of all during this period in the west.

|

Mosaic with a font, mid-5th century Museum of

Byzantine culture, Thessaloniki

Photo source: NGA website |

|

|

|

Perhaps the parallels exist because many artists from the Greek world went to the west during the Iconoclast controversy, spanning most years from 726 to 843. Mosaic artists from the Byzantine Empire peddled their talents in the west, particularly in Carolingian courts of Charlemagne and his sons. From that time forward certain standards of Byzantine representation, such as the long, dark, bearded Jesus on the cross. While we seem to see these images as either icons or mosaics in Greek art, they become symbols in the west, often translated into sculptures of wood, stone or even stained glass.

An interesting parallel of the two exhibitions is the early Byzantine fountain, a wall mosaic of gold, glass and stone in the NGA’s exhibition, which compares well to the 13th century Baptismal font from Hildesheim, showing the Baptism of Christ. The font mosaic is from the Church of the Acheiropoietos in Thessaloniki. It is thought to emulate the fountains and gardens of Paradise. One can visualize of the context in which the fragmentary mosaic was made by watching the film in the exhibition, which shows another wondrous 5th century church in Thessaloniki, the Rotonda Church.

|

A Baptismal Font, 1226, is superb example of Medieval

metalwork from Hildesheim Cathedral. |

The exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum had a life-size

wooden statue of the dead Jesus, dated to the 11th century, originally on a wood cross, now gone. Wood carvers out of Germany were masters of emotional expression. In the iconic

Crucifixion image in the Greek exhibition, a very sad Mary and Apostle John are grieving at the side of Jesus. It’s poignant and emotional, with knit eyebrows, tilted heads and a profoundly felt grief.

|

| Golden Madonna is wood covered in gold, made for St. Michael’s Cathedral before 1002 |

|

The iconographic image of the Theotokos, a Greek type is normally a rigid, enthroned Mary who solidly holds her son, a little emperor. The format expresses that she is the throne, a seat for God in the form of Baby Jesus. From Hildesheim, there is a carved statue which dates to c. 970, carved of wood and covered with a sheet of real good. Both heads are now missing. At one time the statue was covered with jewels, offerings people had given to the statue. In the west, this type became common, called the sedes sapientaie, but the origin is probably Byzantium.

Although heaven is more important than earth, and God and saints in heaven are more powerful than humans, sometimes medieval artists have been capable of revealing the greatest truths about what it’s like to be a human being. In the icons, there is great poignancy and beauty in the eyes. At times the portrayal of grief is overwhelming, as we see on an icon of the Hodegetria image where Mary points the way, the baby Jesus but knows He will die. On the reverse is an excruciatingly painful Man of Sorrows.

|

| Icon of the Virgin Hodegetria, last quarter 12th century, tempera and silver on wood, Kastoria, Byzantine Museum. On the Reverse is a Man of Sorrows |

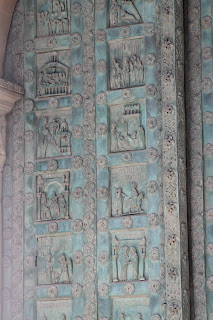

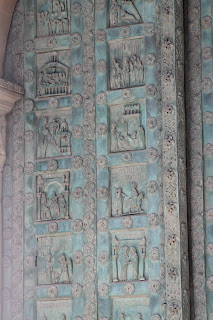

The Metropolitan exhibition of course could not bring the two most important works from Hildesheim, the bronze relief sculptures: a triumphal column with the Passion of Christ and a set of bronze doors for the Cathedral. Completed before 1016, I often think of the figures on the relief panels on those doors as one of the most honest works of art ever created. As God convicts Adam of eating the forbidden fruit, Adam crosses his arm to point to Eve who twists her arms pointing downward to a snake on the ground. We may laugh because God’s arm seems to be caught in his sleeve as he points to Adam. Though this medieval artist/metalsmith (Bishop Bernward?) may not have understood anatomy and perspective, he understood how easy it is for humans to pass the blame and not take responsibility for their actions.

|

| The Expulsion, before 1016, detail of bronze door, St. Michael’s, Hildesheim |

Medieval artists in both the Greek and Latin churches are normally not known by name. After all, their work was for God, not for themselves, for money or for fame.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Nov 20, 2013 | Archeology, Architecture, Christianity and the Church, Roman Art, The Middle Ages

|

A first century temple to Mars, or possibly Janus, near Autun (ancient

Augustodunum) in Burgundy may have inspired the large churches of this region

in the 11th and 12th centuries. Only a fraction of this building remains today. Here,

a family from the Netherlands had a picnic while climbing the ruin.

|

A movement to dot the landscape of Europe with large churches in the 11th and 12th centuries was fueled by deep Christian faith, but, initially, the important building technologies had inspiration from the remains of ancient, pagan buildings. The population surged at this time and the last invaders, the Vikings and Magyars, had settled down.

|

A transept of St. Lazare, Autun, built around 1120

has tall arches and a blind arcade like many

late Roman buildings. The rib vaults

vault are an innovation of Romanesque |

Romanesque is the name given today to that style of art, reflecting its common traits with Roman architecture: arches, barrel vaults and groin vaults. Although the library at the monastery of Cluny, in Burgundy, had a copy of the Roman architect Vitruvius’ treatise on architecture which described how to make concrete, the medieval builders did not use concrete. They looked at the stones around them, used their compasses and measures, and created a marvelous revival of monumental building. It was a time of pilgrimages and Crusades, and stone masons moved from place to place, spreading architectural ideas.

|

Porte d’Arroux is the best preserved of four gates

erected in Autun during Roman times. |

In the first centuries of Christianity, builders reused Roman columns, which were plentiful in the forums surrounding civic buildings of the ancient cities. Romanesque sculptors invented their own style of column capitals and used them to tell stories in sculpture. Even in monastery churches, Romanesque builders needed to allow for pilgrims coming to see relics and they built big. For the proportion of nave arcades to the upper levels of churches, the gallery and clerestory, they took some cues from Roman buildings, aqueducts and gates and made the upper levels smaller. At times, late Roman architecture of the 3rd and 4th centuries, which tended to be more organic and experimental than buildings from the Augustan age, probably served as models.

|

Porte St-Andre is one of the two Roman gates standing in Autun, Burgundy,

although much of it was restored in the 19th century. |

Outside of Autun, the remains of a temple to Mars or Janus, of Gallic fanum design, has magnificent high arches that reminded me of Arches National Park in Utah. Two Roman gates and the remnants of a Roman theater are in Autun, also. It’s surprising so much remains, because the city was sacked by both Saracens in the 8th century and Vikings in the 9th century. Because of the richness of the ruins, it’s not surprising that some of the greatest cathedrals from Romanesque times were built in the Burgundian region of east-central France: St. Lazare in Autun, Ste. Madeleine in Vézelay, St. Philibert at Tournus, and, above all, St. Pierre at Cluny. The church at Cluny remained the largest Christian church until St. Peter’s, Rome, was completed in the 17th century. Most of it was damaged during the French Revolution.

|

The Baths of Constantine, Arles

dated to the 4th century |

Further south, in Arles, the Baths of Constantine, built in the 4th century, may have inspired medieval builders. (It’s hard to know how much was built over it or covered up at the time.) It has clusters of bricks which alternate with limestone in forming the arches. This Roman decorative variation was sometimes imitated. The curved end and semi-dome of the “tepidarium” (warm bath) resembles the apse end of churches from the Middle Ages. In fact, curved exedrae, which are shaped like semi-circles, were ever present in all types of Roman buildings. Probably the best example of Roman vaulting techniques were seen in the theatre and an amphitheater in Arles, dating to the early empire.

|

The curved Roman exedra form of this

bath building was imitated in the curved

east end of Romanesque churches |

Nearby was a famous aqueduct, the Pont du Gard, with three rows of superimposed arches harmoniously proportioned like the two or three levels in the naves of Romanesque churches. In Nîmes, there was also a Roman tower, an amphitheatre, and a theatre that has vanished. The Maison Carrée in Nîmes, a famous Augustan temple, served as inspiration mainly because of its decorative details. The straight post-and-lintel construction did not offer practical solutions for the large size desired in the Romanesque churches. (In neoclassical times, Thomas Jefferson used the Maison Carrée as the model Virginia’s state capital building.)

Most art historians talk of the relationship between the design of triumphal arches and the facades of churches in Provence. Certainly the abundant decorative details of churches in Provence, including Saint Trophime in Arles, is in imitation of classical decorative motifs. This church and others in Provence had continuous bands for narrative sculpture, called friezes, as on classical buildings.

|

The layout of St.-Gilles-du-Gard near Nîmes, France, is often compared to

the design of Roman triumphal arches. The frieze is a continuous narrative in sculpture.

Additionally, the shape of the round tympanum and pilasters has parallels with the

so-called Temple of Diana, below left. |

|

In Nîmes, the remains on the inside of a 3rd

century Temple to Diana, may have inspired

the design of the tympanum and barrel vault,

standards for Romanesque church design

|

However, I note the similarity between St.-Gilles-du-Gard, in the Rhone delta, and the building traditionally considered a Temple of Diana in Nîmes, probably from the 3rd or 4th century. It provides a model for the shape of a tympanum, an important field for sculpture over the doorway of Romanesque churches. Only portions of the interior remain, with the beginning of a reinforced barrel vault, pediments and pilasters. It is easy to see how the shapes of Roman buildings determined some shapes in the churches and cathedrals. Certainly the doorways at St.-Gilles resemble three-part triumphal arches, like the Arch of Constantine or triumphal arch in Orange (see photo on bottom).

|

At St-Gilles-du-Gard, two heads look like Roman

portraits. One that grows out of a Corinthian capital

is dressed like a priest. A snake is approaching the

other head. Only an artist of the Middle Ages

could use classicism with so much wit and whimsy! |

When Romanesque builders took inspiration from ancient art and architecture, they added much of their own creativity and ingenuity. They began to make the arches taller, the vaults more elaborate and pointed, reflecting their borrowings from Islamic architecture during and after the Crusades. (One such Romanesque Church, which took in so many diverse influences, including sculpture in the style of Provence, is Monreale Cathedral, discussed previously on another page in this blog.)

|

The Triumphal Arch in Orange, France was a

richly ornamented, a trait carried over in the

Romanesque churches of Provence |

When it came to sculpture, they were very imaginative, whimsical and emotionally expressive of the religious zeal of a bygone age. At times, they re-used classicism in ways that would not have been acceptable at all, as in Sainte-Marie de Nazareth in Vaison-la Romaine.

Romanesque architecture developed very quickly and led to the Gothic style, which began in Paris around 1150 and spread almost everywhere within a century.

The Via Lucis website has the best and most comprehensive photographs and explanations of Romanesque art and architecture.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Nov 28, 2012 | Architecture, Christianity and the Church, Mosaics, Sculpture, Sicily, The Middle Ages

|

Sicily was controlled or settled at various times by Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Saracens,

Normans and Spaniards. This view is Monreale, in the north, east of Palermo. |

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

|

Bonnano of Pisa cast the bronze doors

in 1185 |

A Norman ruler, William II (1154-89), built Monreale Cathedral between 1174 and 1185. When the Roman Empire first became Christian, Sicily reflected the ethnic Greeks who lived on the island. In the 8th century, Saracens conquered Sicily and held it for two centuries, although a majority of residents were Christians of the Byzantine tradition. William the Conqueror’s brother Roger took over the island in 1085, but allowed the other groups to live peacefully and practice their religion. Normans, Lombards and other “Franks” also settled on the island, but the Norman rule between the late 11th and late 13th centuries was quite tolerant. By the 13th century, most residents adopted the Roman Catholic faith. Germans, Angevins and finally, the Spanish took control of the island.

|

This pair of figural capitals in the cloister could be a biblical

story such as Daniel in the Lion’s Den or even a pagan tale |

Monreale Cathedral was built on a basilican plan in the Romanesque style that dominated Western Europe in the 12th century, although the Gothic style had already taken hold in Paris at the time of this building. It is based on the longitudinal cross plan with a rounded east end. Two towers flank the facade. (This Cathedral ranks right up with Chartres and Notre-Dame of Paris, as one of the world’s most beautiful churches.)

|

Capitals feature men, beasts and beautiful

acanthus leaf designs |

In the artistic and decorative details, there is great richness. The portal has one of the few remaining sets of bronze doors from the Romanesque period. These doors were designed and cast by a Tuscan artist, Bonanno da Pisa. A cloister, similar to the cloisters of all abbey churches has a beautiful courtyard with figural capitals. Its pointed arches betray Islamic influence. The sculptors who carved the capitals are thought to have come from Provence in southern France, perhaps because of similarity in style to abbey churches near Arles and Nîmes, places with a strong Roman heritage. However, on the exterior apse of the church is a surprise. It has the rich geometry of Islamic tile patterns. Islamic artists who lived in the vicinity of Monreale were probably called upon to do this work.

|

| Islamic artisans decorated the eastern side of the church with rich geometric patterns |

The Greek artists who decorated the Cathedral’s interior were amongst the finest mosaic artists available. The Norman ruler may have brought these great artisans from Greece. Monreale Cathedral holds the second largest extant collection of church mosaics in the world. The golden mosaics completely cover the walls of the nave, aisles, transept and apse – amounting to 68,220 square feet in total. Only the mosaics at Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey, cover more area, although this cycle is better preserved. The narrative images gleam with heavenly golden backgrounds, telling the stories of Biblical history. The architecture is mainly western Medieval while imagery is Byzantine Greek.

|

| Mosaics in the nave and clerestory of Monreale Cathedral |

A huge Christ Pantocrator image that covers the apse is perhaps the most beautiful of all such images, appearing more calm and gentle than Christ Pantocrator (meaning “almighty” or “ruler of all”) on the dome of churches built in Greece during the Middle Ages. The artists adopted an image used in the dome of Byzantine churches into the semicircular apse behind the altar of this western style church. Meant to be Jesus in heaven, as described in the opening words of John’s gospel, the huge but gentle figure casts a gentle gaze and protective blessing gesture over the congregation. He is compassionate as well as omnipotent.

|

Christ Pantocrator, an image in the dome of Greek churches, spans the apse

of this western Romanesque church. |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Nov 16, 2012 | Christianity and the Church, National Gallery of Art Washington, Raphael, Renaissance Art

Last weekend the annual Sydney J. Freedberg Lecture on Italian Art at the National Gallery of Art was “Not a Painting But a Vision.” Andreas Henning, curator from Dresden, Germany, spoke about The Sistine Madonna, a magnificent altarpiece Raphael painted in 1512 which is now in the Dresden State Art Museum. I have written about it in a previous blog, comparing the Mary of this painting to the Raphael’s lovely image of inner and outer beauty in La Donna Velata.

However, as the title suggested, it is painting of a vision and that Mary is not of this world. She has facial features of that generic beauty similar to those of the Donna Velata, but she is more ethereal and otherworldly. As much as we may want to reach out and hug the baby Jesus, we can’t. The Madonna also carries a tinge of sadness in this image, a practice artists used to reveal Mary recognition that her Son will die someday.

However, two saints, Saint Sixtus and Saint Barbara have brighter colors and lead the transition to the audience on earth. The curator explained that they represent a reconciliation of opposites, as we often find in Raphael’s paintings. They are male and female, old and young, the active life and the contemplative life. But the truth is that they, too, are in heaven.

When the Sistine Madonna was completed and set as an altarpiece in a monastery church in Piacenza, we must imagine curtains framing the Mary, her veil blowing in a wind, as separating one world from another. The drama is in the relationship of the audience to the vision in the work of art. Only the saturated green curtains and a balustrade on bottom are meant to be part of the material world. In fact, in this visionary painting, Raphael has gone behind the Renaissance perspective which aims for imitation of reality. He anticipated the triumphant late Renaissance artist Correggio and the visionary art of Baroque, such as Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa.

I’ve never seen this painting, but was thrilled to view the new slides since the painting’s cleaning. In the background, the clouds reveal the faces of many more cherubs. There are 42 faces in the clouds. (These faces are mainly visible in first image on the upper left side.) What glorious illusion!

The curator also pointed out that these sweet and precious angels, who look upward in observation and wonder, were an afterthought which Raphael felt the composition needed them for completion. What impeccable images of innocence, charm and love!

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Dec 5, 2011 | Art Appreciation: Visual Analysis, Baroque Art, Caravaggio, Christianity and the Church, Georges de la Tour, National Gallery of Art Washington

Martha and Mary Magdalene, c. 1598, shows the saint at the moment of her conversion. It is from the Detroit Institute of Arts, but is currently on view in Caravaggio and His Followers, at the Kimbell Museum of Art

In Caravaggio’s remarkable version of the Mary Magdalen story, he painted the moment of her transition from sinner to saint. As much as Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code popularized the idea that the Church demonized Mary Magdalen, more commonly she was idealized in art as a saint who turned her life around. The painter Michelangelo Merisi, who is nicknamed Caravaggio, was demonized in his lifetime for his shockingly realistic paintings and his own “sinful” life. (He was charged with murder and often on the run.)

The inclusion of Martha with Mary Magdalen and other objects requires the viewer to interpret the symbolism. Martha is seated with her back to the viewer, with only one shoulder and her hands hit by Caravaggio’s dramatic lighting. On the table are a comb, powder puff and mirror, symbols of vanity. Mary points to her chest holding a flower, while her other hand points emphatically to a diamond square of radiant light on the edge of the convex mirror.

The naturalistic light, seemingly projected from a window, is also a divine light, the ray of God which has inspired the worldly Mary Magdalen to “see the light.” In the moment that Caravaggio highlighted and caught in paint, as if on camera, we witness spiritual transition. From this point on she will give up her luxury and prostitution to follow Jesus. By using models who resemble contemporary people in Rome, rather than Biblical characters, the viewers were supposed to identify with the personal nature of the conversion process.

Light is concentrated in a few important places: Martha’s hands, Mary’s face and chest, the hand and patch of light on the mirror. Sister Martha’s hands are lit because she is pleading for Mary to change (and perhaps counting her sins and/or the reasons she should convert). Mary answers by pointing precisely to that light on the mirror.

Perhaps because Mary Magdalen was seen as an instrument of change, and as the most loyal companion of Jesus in his death, she was greatly idolized in the Middle Ages. The church of Sainte-Madeleine, Vezelay, in Burgundy, was a site of her relics and one of the most important of all pilgrimage churches. However, in the late 13th century, a 3rd century Christian tomb discovered in the crypt of a church in Provence was connected to Mary Magdalen. The site of her devotion then moved to this church and another site in the delta of the Rhone, where legend claimed she had relocated after Jesus’ death.

After seeing Caravaggio’s painting of Mary Magdalen, I thought differently of Georges de la Tour’s The Penitent Magdalen at the National Gallery. Like Caravaggio, he used a contemporary young woman as his model. Yet this contemplative scene omits symbols of vanity and the light-dark contrast comes from candlelight hidden behind a skull. As Mary looks in the mirror, the skull is reflected rather than her face, as de la Tour has artfully manipulated perspective. Life as a sinner leads to a spiritual death. Death is inevitable, but if she chooses to follow Jesus she will die of the self and be reborn in new life.

Here Mary Magdalen may either be pondering her fate before conversion, or thinking of her wish to be reunited with Jesus in eternity later in life. Oddly, she caresses the skull as if wanting to die, perhaps because death for a person at peace with God is ultimate goal and preferable to life on earth. The shape of the skull mimics, in reverse, the shape of her sleeve, arm and hand, showing her intimate connection to thoughts of death. In his view, we are also encouraged to ponder our actions and/or sins and consider our life in eternity. Personal faith is in important factor of both the Reformation and Counter-Reformation at this time, although only the Catholic artists would portray  saints. De la Tour leaves the meaning ambiguous, unlike Caravaggio who shows a transitional moment.

saints. De la Tour leaves the meaning ambiguous, unlike Caravaggio who shows a transitional moment.

Georges de la Tour, The Repentant Magdalene, c. 1635, at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, shows her in a contemplative mode, perhaps thinking of death.

In the 6th century, Pope Gregory gave a sermon suggesting Mary Magdalen had been a prostitute before following Jesus. (Of her past, the Bible refers to the seven demons Jesus cast out of her, a vague description.) Although the church usually portrayed her to show that salvation is possible to all who ask for forgiveness, the model for Caravaggio’s Mary Magdalen was Fillide Melandroni, one of Rome’s most notorious courtesans. Neither she nor Caravaggio–who revolutionized art in his time–seem to have undergone a spiritual revolution. Caravaggio was frequently in fights and in 1606 he appears to have gotten into a fight with another man over Fillide, this remarkable woman.

(Note: Caravaggio’s more famous paintings of religious calling/conversion are The Calling of St. Matthew and The Conversion of St. Paul, both in Rome and done around 1601. This artist’s life is always a fascination to the public. There is a new biography about him by Andrew Graham-Dixon, Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane, which may try to explain the contradictions of his life. A biography I read a long time ago is Desmond Seward, Caravaggio: A Passionate Life.)

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments