by Julie Schauer | Feb 25, 2014 | Byzantine Art, Cathedral of Hildesheim, Christianity and the Church, Exhibition Reviews, Metalwork, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mosaics, National Gallery of Art Washington, The Middle Ages

Archangel Michael, First half 14th century tempera on wood, gold leaf

overall: 110 x 80 cm (43 5/16 x 31 1/2 in.) Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens

Gold radiates throughout dimly-lit rooms of the National Gallery of Art’s exhibition, Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Art from Greek Collections. Some 170 important works on loan from museums in Greece trace the development of Byzantine visual culture from the fourth to the 15th century. Organized by the Benaki Museum in Athens, it will be on view until March 2 and then at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles beginning April 19. The National Gallery has a done a great job organizing the show, getting across themes of both spiritual and secular life spanning more than 1000 years. The exhibition design is masterful and includes a film about four key Greek churches. The photography is exquisite and provides the full context for the Byzantine church art.

There are dining tables, coins, ivories, jewelry and other objects, but it’s the mosaics which I find most captivating, and this exhibition allows a close-up view. Their nuances of size and shape can be closely observed here, but not in slides or in the distance. Byzantine artists gradually replaced stone mosaics with glass tesserae, painting gold leaf behind the glass to portray backgrounds for the figures. It was the Byzantines created these wondrous images by transforming the Greco-Roman tradition of floor mosaics to that of wall mosaics.

|

| Van Eyck, St John the Baptist, det-Ghent Altarpiece |

|

|

New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art recently hosted another exhibition of the Middle Ages, “Treasures from Hildesheim,” works from the 10th through 13th centuries from Hildesheim Cathedral in Germany. Even though Greek Christians of Byzantine world officially split from Rome in the 11th century, the two exhibitions show that the art of east and west continued to share much in terms of iconography and style. Jan Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, from the 15th century, contains a Deesis composed of Mary, Jesus and John the Baptist, in its center, proving how persistent Byzantine iconography was in the West. That altarpiece shows the early Renaissance continuation of imagining heaven as glistening gold and jewels.

Church architecture evolved very differently however, with the Latin church preferring elongated churches with the floor plan of Roman basilicas. The ritual requirements of the Orthodox Church resulted in a more compact form using domes, squinches and half-domes. Fortunately, the National Gallery’s exhibition has a lot of information about Orthodox churches, their layout and how the Iconostasis (a screen for icons) divided the priests from the congregation.

|

| Reliquary of St. Oswald, c. 1100, is silver gilt |

Both cultures re-used works from antiquity. In the East, the statue heads of pagan goddesses could become Christian saints with a addition of a cross on their foreheads. In the west, ancient portrait busts inspired gorgeous metalwork used for the relics of saints, such as the reliquary of St. Oswald, which actually contained a portion of this 7th century English saint’s skull. Mastering anatomy, perspective and foreshortening was not as important an aim as it was to evoke the glory and golden beauty of heaven as it was imagined to be. The goldsmiths and metalsmiths were considered the best artists of all during this period in the west.

|

Mosaic with a font, mid-5th century Museum of

Byzantine culture, Thessaloniki

Photo source: NGA website |

|

|

|

Perhaps the parallels exist because many artists from the Greek world went to the west during the Iconoclast controversy, spanning most years from 726 to 843. Mosaic artists from the Byzantine Empire peddled their talents in the west, particularly in Carolingian courts of Charlemagne and his sons. From that time forward certain standards of Byzantine representation, such as the long, dark, bearded Jesus on the cross. While we seem to see these images as either icons or mosaics in Greek art, they become symbols in the west, often translated into sculptures of wood, stone or even stained glass.

An interesting parallel of the two exhibitions is the early Byzantine fountain, a wall mosaic of gold, glass and stone in the NGA’s exhibition, which compares well to the 13th century Baptismal font from Hildesheim, showing the Baptism of Christ. The font mosaic is from the Church of the Acheiropoietos in Thessaloniki. It is thought to emulate the fountains and gardens of Paradise. One can visualize of the context in which the fragmentary mosaic was made by watching the film in the exhibition, which shows another wondrous 5th century church in Thessaloniki, the Rotonda Church.

|

A Baptismal Font, 1226, is superb example of Medieval

metalwork from Hildesheim Cathedral. |

The exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum had a life-size

wooden statue of the dead Jesus, dated to the 11th century, originally on a wood cross, now gone. Wood carvers out of Germany were masters of emotional expression. In the iconic

Crucifixion image in the Greek exhibition, a very sad Mary and Apostle John are grieving at the side of Jesus. It’s poignant and emotional, with knit eyebrows, tilted heads and a profoundly felt grief.

|

| Golden Madonna is wood covered in gold, made for St. Michael’s Cathedral before 1002 |

|

The iconographic image of the Theotokos, a Greek type is normally a rigid, enthroned Mary who solidly holds her son, a little emperor. The format expresses that she is the throne, a seat for God in the form of Baby Jesus. From Hildesheim, there is a carved statue which dates to c. 970, carved of wood and covered with a sheet of real good. Both heads are now missing. At one time the statue was covered with jewels, offerings people had given to the statue. In the west, this type became common, called the sedes sapientaie, but the origin is probably Byzantium.

Although heaven is more important than earth, and God and saints in heaven are more powerful than humans, sometimes medieval artists have been capable of revealing the greatest truths about what it’s like to be a human being. In the icons, there is great poignancy and beauty in the eyes. At times the portrayal of grief is overwhelming, as we see on an icon of the Hodegetria image where Mary points the way, the baby Jesus but knows He will die. On the reverse is an excruciatingly painful Man of Sorrows.

|

| Icon of the Virgin Hodegetria, last quarter 12th century, tempera and silver on wood, Kastoria, Byzantine Museum. On the Reverse is a Man of Sorrows |

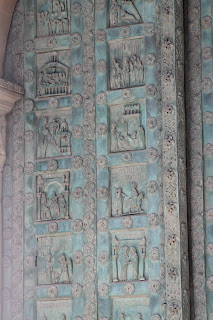

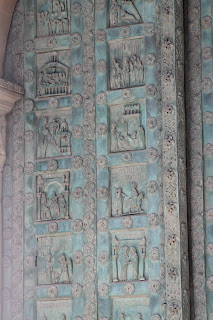

The Metropolitan exhibition of course could not bring the two most important works from Hildesheim, the bronze relief sculptures: a triumphal column with the Passion of Christ and a set of bronze doors for the Cathedral. Completed before 1016, I often think of the figures on the relief panels on those doors as one of the most honest works of art ever created. As God convicts Adam of eating the forbidden fruit, Adam crosses his arm to point to Eve who twists her arms pointing downward to a snake on the ground. We may laugh because God’s arm seems to be caught in his sleeve as he points to Adam. Though this medieval artist/metalsmith (Bishop Bernward?) may not have understood anatomy and perspective, he understood how easy it is for humans to pass the blame and not take responsibility for their actions.

|

| The Expulsion, before 1016, detail of bronze door, St. Michael’s, Hildesheim |

Medieval artists in both the Greek and Latin churches are normally not known by name. After all, their work was for God, not for themselves, for money or for fame.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Nov 20, 2013 | Archeology, Architecture, Christianity and the Church, Roman Art, The Middle Ages

|

A first century temple to Mars, or possibly Janus, near Autun (ancient

Augustodunum) in Burgundy may have inspired the large churches of this region

in the 11th and 12th centuries. Only a fraction of this building remains today. Here,

a family from the Netherlands had a picnic while climbing the ruin.

|

A movement to dot the landscape of Europe with large churches in the 11th and 12th centuries was fueled by deep Christian faith, but, initially, the important building technologies had inspiration from the remains of ancient, pagan buildings. The population surged at this time and the last invaders, the Vikings and Magyars, had settled down.

|

A transept of St. Lazare, Autun, built around 1120

has tall arches and a blind arcade like many

late Roman buildings. The rib vaults

vault are an innovation of Romanesque |

Romanesque is the name given today to that style of art, reflecting its common traits with Roman architecture: arches, barrel vaults and groin vaults. Although the library at the monastery of Cluny, in Burgundy, had a copy of the Roman architect Vitruvius’ treatise on architecture which described how to make concrete, the medieval builders did not use concrete. They looked at the stones around them, used their compasses and measures, and created a marvelous revival of monumental building. It was a time of pilgrimages and Crusades, and stone masons moved from place to place, spreading architectural ideas.

|

Porte d’Arroux is the best preserved of four gates

erected in Autun during Roman times. |

In the first centuries of Christianity, builders reused Roman columns, which were plentiful in the forums surrounding civic buildings of the ancient cities. Romanesque sculptors invented their own style of column capitals and used them to tell stories in sculpture. Even in monastery churches, Romanesque builders needed to allow for pilgrims coming to see relics and they built big. For the proportion of nave arcades to the upper levels of churches, the gallery and clerestory, they took some cues from Roman buildings, aqueducts and gates and made the upper levels smaller. At times, late Roman architecture of the 3rd and 4th centuries, which tended to be more organic and experimental than buildings from the Augustan age, probably served as models.

|

Porte St-Andre is one of the two Roman gates standing in Autun, Burgundy,

although much of it was restored in the 19th century. |

Outside of Autun, the remains of a temple to Mars or Janus, of Gallic fanum design, has magnificent high arches that reminded me of Arches National Park in Utah. Two Roman gates and the remnants of a Roman theater are in Autun, also. It’s surprising so much remains, because the city was sacked by both Saracens in the 8th century and Vikings in the 9th century. Because of the richness of the ruins, it’s not surprising that some of the greatest cathedrals from Romanesque times were built in the Burgundian region of east-central France: St. Lazare in Autun, Ste. Madeleine in Vézelay, St. Philibert at Tournus, and, above all, St. Pierre at Cluny. The church at Cluny remained the largest Christian church until St. Peter’s, Rome, was completed in the 17th century. Most of it was damaged during the French Revolution.

|

The Baths of Constantine, Arles

dated to the 4th century |

Further south, in Arles, the Baths of Constantine, built in the 4th century, may have inspired medieval builders. (It’s hard to know how much was built over it or covered up at the time.) It has clusters of bricks which alternate with limestone in forming the arches. This Roman decorative variation was sometimes imitated. The curved end and semi-dome of the “tepidarium” (warm bath) resembles the apse end of churches from the Middle Ages. In fact, curved exedrae, which are shaped like semi-circles, were ever present in all types of Roman buildings. Probably the best example of Roman vaulting techniques were seen in the theatre and an amphitheater in Arles, dating to the early empire.

|

The curved Roman exedra form of this

bath building was imitated in the curved

east end of Romanesque churches |

Nearby was a famous aqueduct, the Pont du Gard, with three rows of superimposed arches harmoniously proportioned like the two or three levels in the naves of Romanesque churches. In Nîmes, there was also a Roman tower, an amphitheatre, and a theatre that has vanished. The Maison Carrée in Nîmes, a famous Augustan temple, served as inspiration mainly because of its decorative details. The straight post-and-lintel construction did not offer practical solutions for the large size desired in the Romanesque churches. (In neoclassical times, Thomas Jefferson used the Maison Carrée as the model Virginia’s state capital building.)

Most art historians talk of the relationship between the design of triumphal arches and the facades of churches in Provence. Certainly the abundant decorative details of churches in Provence, including Saint Trophime in Arles, is in imitation of classical decorative motifs. This church and others in Provence had continuous bands for narrative sculpture, called friezes, as on classical buildings.

|

The layout of St.-Gilles-du-Gard near Nîmes, France, is often compared to

the design of Roman triumphal arches. The frieze is a continuous narrative in sculpture.

Additionally, the shape of the round tympanum and pilasters has parallels with the

so-called Temple of Diana, below left. |

|

In Nîmes, the remains on the inside of a 3rd

century Temple to Diana, may have inspired

the design of the tympanum and barrel vault,

standards for Romanesque church design

|

However, I note the similarity between St.-Gilles-du-Gard, in the Rhone delta, and the building traditionally considered a Temple of Diana in Nîmes, probably from the 3rd or 4th century. It provides a model for the shape of a tympanum, an important field for sculpture over the doorway of Romanesque churches. Only portions of the interior remain, with the beginning of a reinforced barrel vault, pediments and pilasters. It is easy to see how the shapes of Roman buildings determined some shapes in the churches and cathedrals. Certainly the doorways at St.-Gilles resemble three-part triumphal arches, like the Arch of Constantine or triumphal arch in Orange (see photo on bottom).

|

At St-Gilles-du-Gard, two heads look like Roman

portraits. One that grows out of a Corinthian capital

is dressed like a priest. A snake is approaching the

other head. Only an artist of the Middle Ages

could use classicism with so much wit and whimsy! |

When Romanesque builders took inspiration from ancient art and architecture, they added much of their own creativity and ingenuity. They began to make the arches taller, the vaults more elaborate and pointed, reflecting their borrowings from Islamic architecture during and after the Crusades. (One such Romanesque Church, which took in so many diverse influences, including sculpture in the style of Provence, is Monreale Cathedral, discussed previously on another page in this blog.)

|

The Triumphal Arch in Orange, France was a

richly ornamented, a trait carried over in the

Romanesque churches of Provence |

When it came to sculpture, they were very imaginative, whimsical and emotionally expressive of the religious zeal of a bygone age. At times, they re-used classicism in ways that would not have been acceptable at all, as in Sainte-Marie de Nazareth in Vaison-la Romaine.

Romanesque architecture developed very quickly and led to the Gothic style, which began in Paris around 1150 and spread almost everywhere within a century.

The Via Lucis website has the best and most comprehensive photographs and explanations of Romanesque art and architecture.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Nov 28, 2012 | Architecture, Christianity and the Church, Mosaics, Sculpture, Sicily, The Middle Ages

|

Sicily was controlled or settled at various times by Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Saracens,

Normans and Spaniards. This view is Monreale, in the north, east of Palermo. |

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

The island of Sicily has a central location in the Mediterranean Sea which has made it the most conquered region in Italy, and perhaps the world. Even the Normans who ruled England also went to Sicily. Despite the violence of the Middle Ages, today we can recognize that era in Sicily as providing an example of cross-cultural cooperation which is to be admired. Islam, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism lived in tandem and with tolerance during most of that period. The different religious and cultural groups poured the best work of various artistic traditions in to the building of Monreale Cathedrale, about 8 miles outside of Palermo.

|

Bonnano of Pisa cast the bronze doors

in 1185 |

A Norman ruler, William II (1154-89), built Monreale Cathedral between 1174 and 1185. When the Roman Empire first became Christian, Sicily reflected the ethnic Greeks who lived on the island. In the 8th century, Saracens conquered Sicily and held it for two centuries, although a majority of residents were Christians of the Byzantine tradition. William the Conqueror’s brother Roger took over the island in 1085, but allowed the other groups to live peacefully and practice their religion. Normans, Lombards and other “Franks” also settled on the island, but the Norman rule between the late 11th and late 13th centuries was quite tolerant. By the 13th century, most residents adopted the Roman Catholic faith. Germans, Angevins and finally, the Spanish took control of the island.

|

This pair of figural capitals in the cloister could be a biblical

story such as Daniel in the Lion’s Den or even a pagan tale |

Monreale Cathedral was built on a basilican plan in the Romanesque style that dominated Western Europe in the 12th century, although the Gothic style had already taken hold in Paris at the time of this building. It is based on the longitudinal cross plan with a rounded east end. Two towers flank the facade. (This Cathedral ranks right up with Chartres and Notre-Dame of Paris, as one of the world’s most beautiful churches.)

|

Capitals feature men, beasts and beautiful

acanthus leaf designs |

In the artistic and decorative details, there is great richness. The portal has one of the few remaining sets of bronze doors from the Romanesque period. These doors were designed and cast by a Tuscan artist, Bonanno da Pisa. A cloister, similar to the cloisters of all abbey churches has a beautiful courtyard with figural capitals. Its pointed arches betray Islamic influence. The sculptors who carved the capitals are thought to have come from Provence in southern France, perhaps because of similarity in style to abbey churches near Arles and Nîmes, places with a strong Roman heritage. However, on the exterior apse of the church is a surprise. It has the rich geometry of Islamic tile patterns. Islamic artists who lived in the vicinity of Monreale were probably called upon to do this work.

|

| Islamic artisans decorated the eastern side of the church with rich geometric patterns |

The Greek artists who decorated the Cathedral’s interior were amongst the finest mosaic artists available. The Norman ruler may have brought these great artisans from Greece. Monreale Cathedral holds the second largest extant collection of church mosaics in the world. The golden mosaics completely cover the walls of the nave, aisles, transept and apse – amounting to 68,220 square feet in total. Only the mosaics at Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey, cover more area, although this cycle is better preserved. The narrative images gleam with heavenly golden backgrounds, telling the stories of Biblical history. The architecture is mainly western Medieval while imagery is Byzantine Greek.

|

| Mosaics in the nave and clerestory of Monreale Cathedral |

A huge Christ Pantocrator image that covers the apse is perhaps the most beautiful of all such images, appearing more calm and gentle than Christ Pantocrator (meaning “almighty” or “ruler of all”) on the dome of churches built in Greece during the Middle Ages. The artists adopted an image used in the dome of Byzantine churches into the semicircular apse behind the altar of this western style church. Meant to be Jesus in heaven, as described in the opening words of John’s gospel, the huge but gentle figure casts a gentle gaze and protective blessing gesture over the congregation. He is compassionate as well as omnipotent.

|

Christ Pantocrator, an image in the dome of Greek churches, spans the apse

of this western Romanesque church. |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 5, 2012 | Ancient Art, Exhibition Reviews, Greek Art, Memorials, Renaissance Art, Sculpture, The Middle Ages

An exquisite of exhibition “mourning” statues at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, have a beauty and realism that give us something to cry about, a phrase Michelangelo used to describe Flemish painting.

In the 15th century, Flanders was ruled by the Duke of Burgundy and similarities to the Flemish style of painting can be are apparent in the style of sculptors Jean de la Huerta and Antoine de la Moiturier. They learned their art from the great Claus Sluter, a Netherlandish sculptor who worked in Burgundy. The Dukes of Burgundy had one of Europe’s richest courts, in rivalry with the King of France to the west and Holy Roman Empire to the east.

The 40 statues line up as if in a funeral procession. At the exhibition, viewers have a chance to see the statues in more completeness and in a more realistic way than in the location they were originally placed, below the bodies of Duke John the Fearless (Jean sans Peur) and his wife, Marguerite. In the current display, the alabaster figures are seen as they move in space, without the elaborate decorative Gothic frames that confine them. They represent the clergy and family members who had been part of Jean the Fearless’ funeral procession in 1424. The statues are on loan from Dijon, France, while the Musee des Beaux Art is undergoing renovation.

Cowls and hoods identify these figures as mourners in the funeral procession. They are alabaster white with details such as books and belts painted. Larger effigies of the duke and duchess were painted in bright colors to look real.

Cowls and hoods identify these figures as mourners in the funeral procession. They are alabaster white with details such as books and belts painted. Larger effigies of the duke and duchess were painted in bright colors to look real.

Like Rogier van Weyden or the

Master of Dreux Budé , these sculptors drew on both realism and emotionalism in a style that is on the cusp between the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The figures are white with a few painted color details, although mourners and even horses, in the funerary procession actually wore black, hooded robes. A tomb of Philippe Pot, Seneschal of Burgundy, from about 1480 has life-size, hooded black figures which hold up the tomb and give an even more realistic version of a funeral.

Life-sized, hooded, black pallbearers were carved anonymously c. 1480 for the tomb of Philippe Pot, Seneschal of Burgundy. They have a greater sense of actuality but less individual, emotional pathos of the group in traveling exhibition.

Life-sized, hooded, black pallbearers were carved anonymously c. 1480 for the tomb of Philippe Pot, Seneschal of Burgundy. They have a greater sense of actuality but less individual, emotional pathos of the group in traveling exhibition.The small white, alabaster figures, however, are full of passionate emotion, and they move into a a variety of different positions. Their angular cuts of drapery are Gothic in style, but when seen in the round, as on display now, the statues have a 3-dimensional spatial conception of the Renaissance. Fortunately the artists carved them in the round, even though they are not seen this way in the Gothic niches underneath the life-sized, reclining duke and duchess. (In 1793, French revolutionaries damaged the effigies of the duke and duchess who represented the repression of the aristocracy, but left the mourners largely unharmed.)

The statuettes are part of the funerary sarcophagus of Jean sans Peur and Marguerite of Bavaria in the fine arts museum of Dijon. The small mourners walk in a funerary procession but are covered by gothic canopies.

These figures call to mind all the mourning figure in art history who accompany the processions and burials of important historical people, and remind us of the processions like those of Roman emperors. Certainly “mourners” were part of the history of art going back more than 5,000 years. However, I couldn’t think of any mourners from early Medieval art because the Early Christians felt death as triumphant and not a matter of earthly pain.

Although the Burgundian court was probably aware of ancient Roman sarcophagii depicting mourners in the funerary procession, the classical Greek-style Sarcophagus of the Mourning Women has a comparable format. This coffin of c. 350 BC was for a king of Sidon, Lebanon, and the women on bottom were probably part of his harem. Each mourner is carved in relief, standing separately between half-columns, while a chariots travel in a frieze above, perhaps the funerary procession or the rulers trip into afterlife. The women twist and  turn and cry to show their various expressions of grief after the death of a leader. As usual, these mourners serve a god-like ruler, not ordinary citizens.

turn and cry to show their various expressions of grief after the death of a leader. As usual, these mourners serve a god-like ruler, not ordinary citizens.

Eighteen women adorn the bottom of a sarcophagus of c. 350 BC, on view at that archeological museum in Istanbul

Early Greek funerary art attempts to show profound emotion. Both the ancient Greeks and Egyptians had elaborate burial ceremonies for their heroes or rulers that could last weeks or months. Mourners accompany pharoahs in their tombs, as the women below.

To the right, female “professional” mourners with raised arms who accompanied the great Ramses in his funerary procession are painted in his tomb.

Detail from a Greek vase in the Metropolitan Museum of Art has rows of mourning figures on either side of the funerary bier. Similar vases come from a cemetery in Athens and they date to 800-700 BC.

The lives of fallen Greek heroes were celebrated with elaborate games, chariot races and processions, as in the funeral sponsored by Achilles for the death of his friend Patrokles. Geometric style vases, from the 8th century BC, are decorated with scenes from funeral procession. Schematic, stick-like figures raise their arms to show they are grieving for the deceased. The figural design is a composite type: frontal torso, profile face and a single, huge eye.

Even older than Greek and Egyptian representations are two small terra cotta statues from Cernavoda, Romania, c. 4,000 BC. Found in a burial close to the Danube River, these statues could be mourning figures. The man’s arms are raised while the woman’s arm is on her knee, her shape suggesting fertility and hope for continuity. I can’t help but think these little figurines were made by the ancestors of Mycenaean or Dorian Greeks who in a later era migrated down into Greece.

The male figure is sometimes called “The Thinker,” but these clay figures from Cernavoda, Romania may be mourners who accompany an important person in burial. The raised arms to show grief was later used by Greeks. They also remind me of Brancusi and Henry Moore.

The exhibition stays until April 15 in Richmond, the last destination in a 2-year, 7-city tour in the United States, including the New York Metropolitan Museum. Next they will go to the Cluny Museum on Paris before returning home. It will be interesting to see how they are displayed when they go home to Dijon.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 29, 2010 | Ancient Art, Architecture, Baroque Art, Christianity and the Church, Greek Art, Sicily, The Middle Ages

The Cathedral of Sircusa (Syracuse), Sicily is built within the colonnades of Greek temple to Athena from the early 5th century BC. Byzantine Christians converted the ruins of it into their Cathedral in the 7th century. The fluted columns are engaged in the outer side wall, along with triglyphs, metopes, etc. (the parts of the Doric Order in Greek architecture). The arched windows and crenelated top date from the Middle Ages. (It even had been a mosque at one time.) However, around the corner, the facade is thoroughly Baroque, built in 1700s! Old and new don’t clash, though — because they aren’t seen simultaneously.

The Cathedral of Sircusa (Syracuse), Sicily is built within the colonnades of Greek temple to Athena from the early 5th century BC. Byzantine Christians converted the ruins of it into their Cathedral in the 7th century. The fluted columns are engaged in the outer side wall, along with triglyphs, metopes, etc. (the parts of the Doric Order in Greek architecture). The arched windows and crenelated top date from the Middle Ages. (It even had been a mosque at one time.) However, around the corner, the facade is thoroughly Baroque, built in 1700s! Old and new don’t clash, though — because they aren’t seen simultaneously.

Behind the door of this

Cathedral’s Baroque

facade, the simplicity of an

actual Doric temple

colonnades are hidden.

The medieval barrel vault comfortably meets

the ancient Greek

colonnade to form

a side aisle.

The temple’s floor plan easily adapts to the

7th century Basilican plan church. The

darkest components of this plan belong

to the original Doric Greek temple.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments