by Julie Schauer | Feb 16, 2016 | Art and Science, Greater Reston Arts Center, Ramon Cajol, Rebecca Kamen, Steven J. Fowler, Susan Alexjander, theory of relativity

|

| Rebecca Kamen, NeuroCantos, an installation at Greater Reston Arts Center |

Six years ago, The Elemental Garden, an exhibition at Greater Reston Arts Center (GRACE) prompted me to start blogging about art. Like TED talks, the news of something so visually fascinating and mentally stimulating as Rebecca Kamen’s integration of art with sciences needs to spread. GRACE presented her work in 2009 and did a followup exhibition, Continuum, which closed February 13, 2016.

|

| Rebecca Kamen, Lobe, Digital print of silkscreen, 15″ x 22″ |

Like the Elemental Garden, Kamen’s new works visually evoke and replicate scientific principles. For the non-scientist and the scientist, the works and their presentation are fascinating. Kamen worked with a British poet and a composer/musician from Portland, Oregon, each with similar intellectual interests.

Two prints included in the show create a dialogue between her design and the words of poet Steven Fowler. I like how the idea of gray matter is overlapped by darker conduits, in Lobe, above. There’s a wonderful sense of density and depth.

While her last exhibition at GRACE was mainly about the Periodic table in chemistry, this time Rebecca Kamen’s exhibition included additional themes such as neural connectivity, gravitational pull, black holes and other mysteries of the universe. Why use art to talk about science? In a statement for Continuum, Kamen starts with a quote by Einstein: “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science.”

Both art and science are creative endeavors that start with questions. One time Kamen told me that she knows there is some connection between the design of the human brain and the design of the solar system, that has not yet been explained. NeuroCantos, the installation shown in the photo on top, explores this relationship. Floating, hanging cone-like structures made of mylar represent the neuronal networks in the brain, while circular shapes below symbolize the similarity of pattern between the brain and outer space, the micro and macro scales. It investigates “how the brain creates a conduit between inner and outer space through its ability to perceive similar patterns of complexity,” Kamen explained in an interview for SciArt in America, December 2015. The installation brings together neuroscience and astrophysics, but it’s initial spark came from a dialogue with poet Fowler. (They met as fellows at the Salzburg Global Seminar last February and participated in a 5-day seminar exploring The Art of Neuroscience.)

|

| Rebecca Kamen, Portals, 2014, Mylar and fossils |

Nearby another installation, Portals, also features suspended cones hanging over orbital patterns on the floor. The installation interprets the tracery patterns of the orbits of black holes, and it celebrates the 100th anniversary of Einstein’s discovery of general relativity. It’s inspired by gravitational wave physics. To me, it’s just beautiful. I can’t pretend to really understand the rest. The entire exhibit is collaborative in nature, with Susan Alexjander, composer, recreating sounds originating from outer space. The combination of sound, slow movement and suspension is mesmerizing.

Terry Lowenthal made a video projection of “Moving Poems” excerpts from Steven Fowler’s poems and a quote from Santiago Ramon y Cajal, artist and neuroscientist.

There are also earlier works by Kamen, mainly steel and wire sculptures. With names like Synapse, Wave Ride: For Albert and Doppler Effect, they obviously mimic scientific effects as she interprets them. Doppler Effect, 2005, appears to replicate sound waves drawing contrast in how they are experienced from near or far away.

|

| Rebecca Kamen, Doppler Effect, 2005, steel and copper wire |

Kamen is Professor Emeritus at Northern Virginia Community College. She has been an artist-in-residence at the National Institutes of Health. She did research Harvard’s Center for Astrophysics and at the Cajal Institute in Madrid. Her art has been featured throughout the country; while her thoughts and concepts have been shared around the world.

For more information, check out www.rebeccakamen.com, www.oursounduniverse.com (Susan Alexjander) and www.stevenjfowler.com

The Elemental Garden

|

| Elemental Garden, 2011, mylar, fiberglass rods |

To the left is a version of The Elemental Garden in Continuum. An identical version is in the educational program of the Taubman Museum of Art, Roanoke, VA.

(The following is how I described it while writing the original blog back in 2010) Sculptor Rebecca Kamen has taken the elemental table to create a wondrous work of art. The beautiful floating universe of Divining Nature: The Elemental Garden–recently shown at Greater Reston Area Arts Center (GRACE)–is based on the formulas of 83 elements in chemistry. Its amazing that an artist can transform factual information into visual poetry with a lightweight, swirling rhythm of white flowers.

According to Kamen, she had the inspiration upon returning home from Chile. After 2 years of research, study and contemplation, she built 3-dimensional flowers based upon the orbital patterns of each atom of all 83 elements in nature, using Mylar to form the petals and thin fiberglass rods to hold each flower together. The 83 flowers vary in size, with the simplest elements being smallest and the most complex appearing larger. The infinite variety of shapes is like the varieties possible in snowflakes; the uniform white mylar material connects them, but individually they are quite different.

|

| Rebecca Kamen, The Elemental Garden, 2009, as installed in GRACE in 2009 (from artist’s website) |

One could walk in the garden and feel a mystical sensation in the arrangement of flowers, as intriguing as the “floral arrangement” of each single element. After awhile I discovered that the atomic flowers were installed in a pattern based upon the spiral pattern of Fibonacci’s sequence. Medieval writer Leonardo Fibonacci and ancient Indian mathematicians had discovered the divine proportion present in nature. This mystical phenomenon explains the spirals we see in nature: the bottom of a pine cone, the spirals of shells and the interior of sunflowers among other things. Greeks also created this pattern in the “golden section” which defines the measured harmony of their architecture. Kamen wanted to replicate this beauty found in nature

Kamen likened her flowers to the pagodas she had seen in Burma. However, there is an even more interesting, interdisciplinary connection. Research on the Internet brought Kamen to a musician, Susan Alexjander of Portland, OR, who composes music derived from Larmor Frequencies (radio waves)emitted from the nuclei of atoms and translated into tone. Alexjander collaborated, also, and her sound sequences were included with the installation. Putting music and art together with science mirrors the universe and it is pure pleasure to experience this mystery of creation.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 15, 2015 | birds, Chris Allen, Fred Tomaselli, Greater Reston Arts Center, Ingrid Bernhardt, Laurel Roth Hope, Petah Coyne, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Tom Uttech, Walton Ford

|

Fred Tomaselli, Woodpecker, 2009, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

gouache, acrylic, photo collage and epoxy resin on wood, 72″ x 72″ |

I love talking about birds in my Art Appreciation classes, though with a focus very different from from the current SAAM (Smithsonian American Art Museum) exhibition, “The Singing and the Silence: Birds in Contemporary Art.” The exhibition’s message is about man’s relationship to birds, with the accent on environmental issues. My class talks about birds in flight, to symbolize our human aspirations. Flying birds remind us that humans can soar even if we don’t literally know how to fly.

|

Chris Allen, A Grand View, 2010, Stone, beads, fetish

Photo from Pinterest, Bonin Smith |

This exhibition and another excellent exhibition called “Bead,” at GRACE (Greater Reston Arts Center), honor the minutia of creation in thousands or millions of the small details that make up the birds. Both exhibitions are breathtakingly beautiful, must-see experiences, though their purposes are not at all similar. There’s only one week left to see the SAAM show, and almost two left weeks until “Bead” ends on February 28. Two of the 15 artists in “Bead” included birds, but the show also features well-known national artists such as David Chatt and Joyce J. Scott. There are many other masterful and surprising interpretations of beads. A pair of birds sitting on top of Chris Allen’s beaded stones is called A Grand View. Beads are skin for the timeless stones of the earth and Allen’s construction is a metaphor for relationship of body and soul. (Chris Allen reminds me of both a blog I wrote before and the great sculptor I admire, Brancusi.)

Back at SAAM, Fred Tomaselli’s Woodpecker, is a large painting, but its smallest details are mesmerizing. Three of his other large paintings are also in the exhibition, all densely patterned. Tomaselli, originally from Santa Monica, California, recalls growing up with bright colors of Disneyland, but also is quite a naturalist, a bird watcher and a lover of fly fishing. Today an exhibition of his work opens at the Orange County Museum of Art.

|

| Ingrid Bernhardt, Chic Chick, 2014, 5″ x 6″ 4″ papier-mâché, beads and feathers |

As in Woodpecker with its beautiful details, there’s a dedication to perfection in Ingrid Bernhardt’s Chic Chick at GRACE. It’s a papier-mâché bird with added beads and feathers. Tons and tons of the tiniest beads make it very intricate. From the fallen feathers, the artist has made some beautiful earrings which lie beside the bird. It’s quite a novelty and something special to behold. Bernhardt compares her beading technique to the pointillism of Seurat and all the dots of color he used.

|

Laurel Roth Hope, Regalia 63 x 40 x 22 in.

Private Collection

© Laurel Roth Hope. Image courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris

|

Chic Chick’s sheer beauty and attention to detail has lots of competition in the peacocks of California artist, Laurel Roth Hope, currently on view at SAAM. She makes peacocks out of hair clips, fake fingernails, fake eyelashes, jewelry, Swarovski crystal and other beauty symbols. One named Regalia, has all the pride associated with its species, and another sculpture named Beauty, is a composition of two peacocks who play the mating game. This bird traditionally is a symbol of Resurrection and eternal life in Christian art, and the artist evokes a power worthy of that traditional role. Her peacocks are amazingly realistic, but the technique and innovative use of material is an example of how an artist can show us how to see the world in a new way.

|

Laurel Roth Hope, Carolina Parokeet, crocheted yarn on

hand-carved wood pigeon mannequin, Smithsonian

American Art Museum |

Laurel Roth Hope is also concerned about the environment and biodiversity To celebrate certain species that are now extinct, she crocheted sweaters that mimic the coats and plumage of these lost birds. One, Carolina Parokeet, is in the SAAM’s permanent collection. Others in this group include the Passenger Pigeon, The Paradise Parrot and the Dodo. She used her hands to crochet sweaters in beautiful, tiny variegated colors and pattern. Much love goes into her creations. At the same time, we think of so many cultural concepts: beauty, pride, artifice (fake nails and fake eyelashes, loss, death. We ask ourselves: What does the outer coat (outer beauty)mean? What does pride mean if it bites the dust in the end? At the same time, the artist is giving tribute and memory to something that is lost.

|

| Laurel Hope Roth, Beauty, detail from the Peacock series photo from the website |

John James Audubon was America’s master artist of birds. Walton Ford is similarly a naturalist who works with combination techniques–watercolor, gouache, etching, drypoint, etc. He breaks with Audubon with his complex allegorical messages, however. environmental messages, however. Also among the 12 artists in the Smithsonian show, several are bird photographers.

|

Walton Ford, Eothen, 2001

watercolor, gouache, and pencil and ink on paper

40 x 60 in.

The Cartin Collection

Image courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery |

Only one of the artists, Tom Uttech, painted his birds in the way I usually imagine them — in flight. Uttech lives in Wisconsin, and his landscapes come from the North Woods, as well as a provincial park in Ontario. Some of his titles are impossible.

Enassamishhinijweian is my favorite. A bear’s back faces us, as he sits still and calmly observes the world of nature passing by. Multitudes of birds fly. An owl turns to look at us, and even a squirrel flies in the sky. The museum label mentions Uttech’s immersion in nature and his belief in its transformative power, much like Emerson and Thoreau. I’d guess that Uttech is also an admirer of

Heironymous Bosch, a 15th-16th century Dutch painter. He also loved panoramas.

A bear hidden in each of Uttech’s three large panoramic landscapes. These bears are probably the artist himself, or the individual who observes nature.

|

Tom Uttech, Enassamishhinjijweian, 2009, oil on linen, 103″ x112″ Collection of the Crystal Bridges Museum, Bentonville, Arkansas

© Tom Uttech. Image courtesy Alexandre Gallery, New York. Photo by Steven Watson |

Traditionally in art, birds in flight show contact between man and divinity. A bird symbolizes the Holy Spirit. In African and Oceanic cultures, the birds tie a living person to his ancestors. Only one of the artists I noticed at SAAM, Petah Coyne, sees her birds as the travel guides, the conduit between heaven and earth. Her elaborate black and purple sculpture is called Beatrice, after Dante’s beautiful guide through Purgatory, in The Divine Comedy. It’s about 12 feet high, and is dripping with birds and falling flowers. The beautiful work must be seen in person to be appreciated.

The many manifestations of birds reminds us of all the roles they fulfill: the silent and the singing and the flying. We end up with a new, profound appreciation for nature, and the hope to protect its beauty, birds included. These exhibitions helped me to see the vastness of this world, as well as the minutia of its details.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 1, 2014 | Exhibition Reviews, Fiber Arts, Folk Art Traditions, Greater Reston Arts Center, Local Artists and Community Shows, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Women Artists

|

Rania Hassan, Pensive I, II, III, 2009, oil, fiber, canvas, metal wood, Each piece

is 31″h x 12″w x 2-1/2″ It’s currently on view at Greater Reston Arts Center. |

There’s a revival of status and attention given to traditional, highly-skilled arts and crafts made of yarn, thread and materials. “Stitch,” a new show at Greater Reston Arts Center (GRACE), proves that traditional sewing arts are at the forefront of contemporary art, and that fiber is a forceful vehicle for expression. Meanwhile, the National Museum of Women in the Arts puts the historical spin on traditional women’s art in “Workt by Hand,” a collection of stunning quilts from the Brooklyn Museum which were shown in exhibition at their home museum last year.

|

Bars Quilt, ca. 1890, Pennsylvania; Cotton and wool, 83 x 82″;

Brooklyn Museum,

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. H. Peter Findlay, 77.122.3;

Photography by Gavin Ashworth,

2012 / Brooklyn Museum |

Quilts are normally very large and utilitarian in nature. To some historians, American quilts are appreciated as material culture with possible stories of the people who made them, but they also have some vivid abstract patterns and strong color harmonies. Their bold geometric shapes vary and change with different color combinations. Quilting is a folk art since it is a passed down tradition, and the patterns may seem stylized and highly decorative. Yet there is room for tremendous variation, creativity and individual style.

Within the United States there are important regional folk groups whose quilts have a distinctive style, like the Amish quilt, above. Amish designs can have a sophisticated abstraction deeply appreciated during the period of Minimal Art of the 1960s and 1970s. The exhibition outlines distinctions and also shows styles popular at certain times, including Mariners’ Knot quilts around 1840-1860, the Crazy Quilts of the Victorian period and the Double Wedding Ring pattern popular in the Midwest after World War I.

|

| Victoria Royall Broadhead, Tumbling Blocks quilt–detail, 1865-70 Gift of Mrs Richard Draper, Brooklyn Museum of Art. Photo by Gavin Ashworth/Brooklyn Museum. This silk/velvet creation won first place in contests at state fairs in St. Louis and Kansas City. |

, |

|

|

|

|

One beautifully patterned quilt is from Sweden, but the rest of them are made in the USA. The patterns change like an optical illusions when we move near to far, or when we view in real life or in reproduction. There’s the Maltese Cross pattern, Star of Bethlehem pattern, Log Cabin pattern, Basket pattern and Flying Geese pattern, to name a few. The same patterns can come out looking very differently, depending on the maker. An Album Quilt has the signatures of different people who worked on different squares. We know the names of a handful of the quilting artists.

|

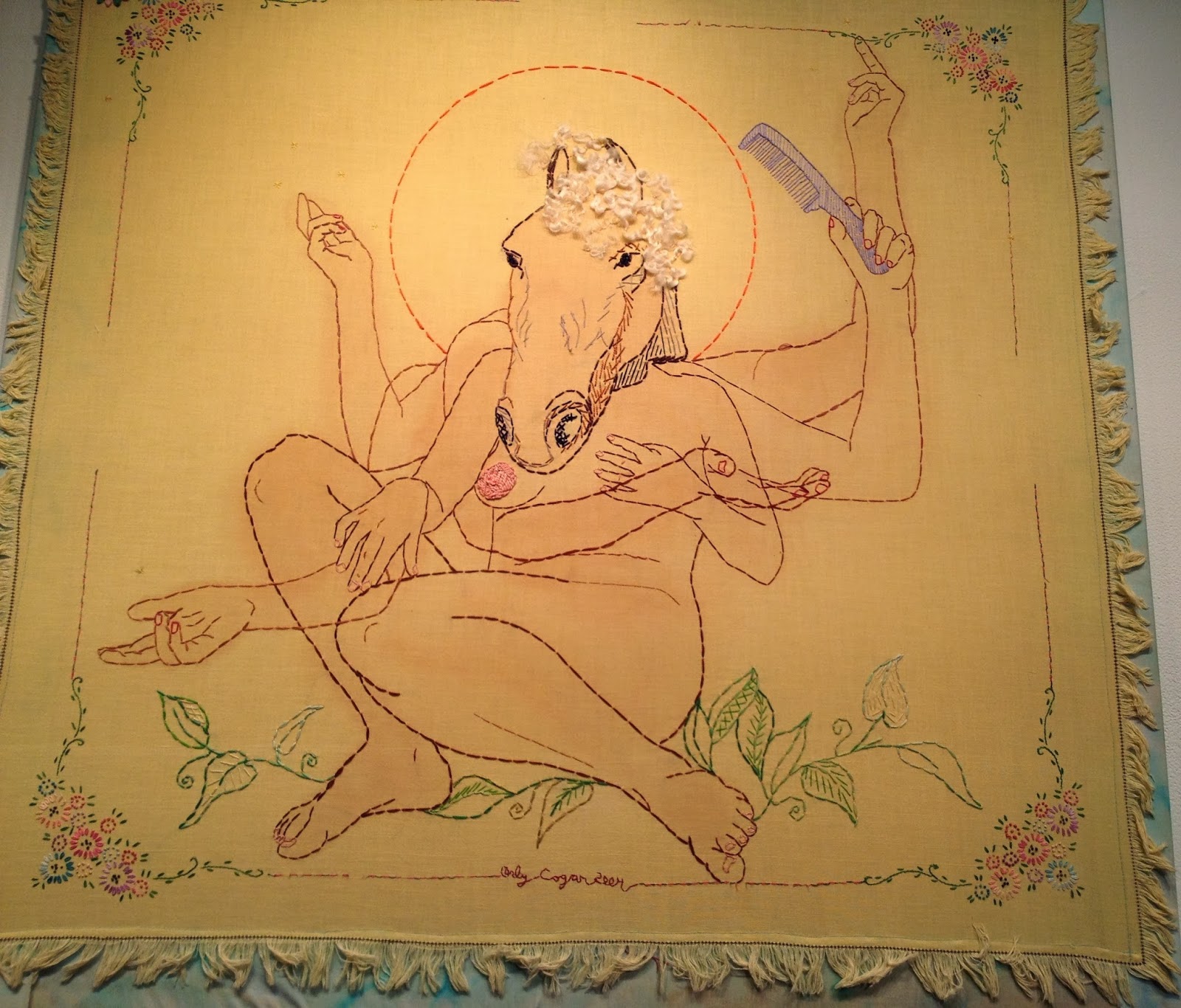

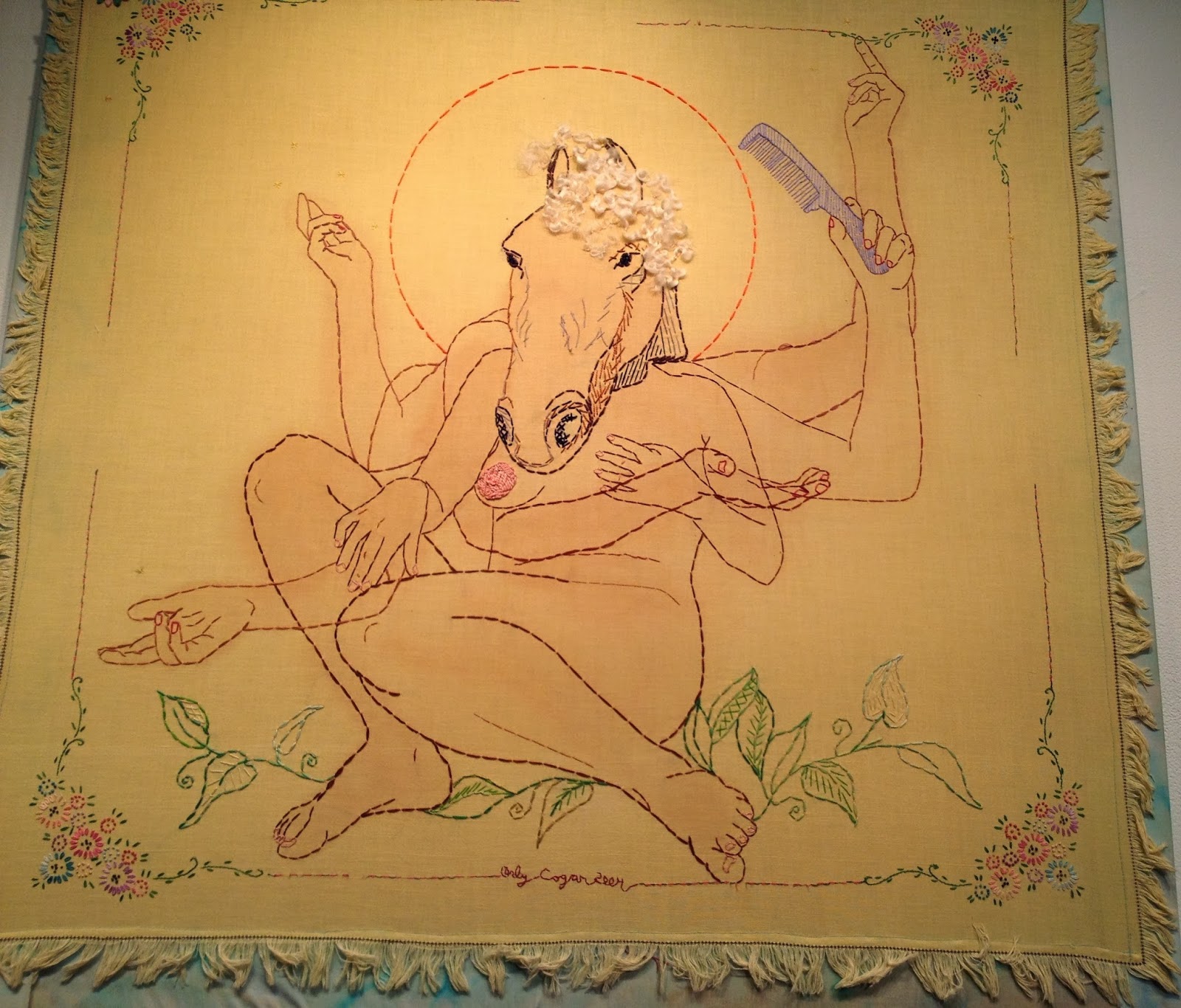

Orly Cogan, Sexy Beast, Hand stitched embroidery

and paint on vintage table cloth, 34″ x 34″ |

While most of the quilts featured in the exhibition were made by anonymous artists, the Reston exhibition includes well-known national figures in fiber art, such as Orly Cogan and Nathan Vincent. Cogan uses traditional techniques on vintage fabrics to explore contemporary femininity and relationships. Her works appear to be large-scale drawings in thread. She adds paint and sews into old tablecloths. I loved the beautiful Butterfly Song Diptich and Sexy Beast, a human-beast combination with multiple arms, like the god Shiva. Vincent, the only man in the show, works against the traditional gender role, crocheting objects of typically masculine themes, such as a slingshot.

|

Pam Rogers, Herbarium Study, 2013, Sewn leaves, handmade

soil and mineral pigments, graphite,

on cotton paper, 22″ x 13-1/2″ |

Most “Stitch” artists are local. Pam Rogers stitches the themes of people, place, nature and myth found in her other works. Kate Kretz, another local luminary of fiber art, embroiders in intricate detail, expressing feelings about motherhood, aging and even the art world.

Kretz’s own blog illuminates her work, including many of the pieces in “Stitch. The pictures there and the detailed photos on an embroidery blog display in sharper detail and explain some of her working methods.

Often she embroiders human hair into the designs and materials, connecting tangible bits of a self with an audience. Kretz explains, “One of the functions of art is to strip us bare, reminding us of the fragility common to every human being across continents and centuries.”

Kretz adds, “The objects that I make are an attempt to articulate this feeling of vulnerability.” Yet some of the works also make us laugh and chuckle, like Hag, a circle of gray hair, Unruly, and Une Femme d’Un Certain Age. Watch out for a dagger embroidered from those gray hairs!

|

Kate Kretz, Beauty of Your Breathing, 2013, Mothers hair from gestation

period embroidered on child’s garment, velvet, 20″ x 25″ x 1″ |

|

Suzi Fox, Organ II, 2014, Recycled

motor wire, canvas, embroidery hoop

12-1/2″ x 8″ x 1-1/2″ |

Kretz is certainly not the only artist who punches us with wit and irony, and/or human hair, into the seemingly delicate stitches. Stephanie Booth combines real hair fibers with photography, and her works relate well to the family history aspect alluded to in NMWA’s quilting exhibition. Rania Hassan is also a multimedia artist who brings together canvas paintings with knitted works. In Dream Catcher and the Pensive series of three, shown at top of this page, she alludes to the fact that knitting is a pensive, meditative act. She painted her own hands on canvases of Pensive I, II, III and Ktog, using the knitted parts to pull together the various parts of three-dimensional, sculptural constructions. She adds wire to the threads for stiffness, although the wires are indiscernible. Suzi Fox uses wire, also, but for delicate, three-dimensional embroideries of hearts, lungs and ribcages (right).

There’s an inside to all of us and an outside. Erin Edicott Sheldon reminds us that stitches are sutures, and she calls her works sutras. Stitches heal our wounds. “I use contemporary embroidery on antique fabric as a canvas to explore the common threads that bind countless generations of women.” Her “Healing Sutras” have a meditative quality, recalling the ancient Indian sutras, the threads that hold all things together.

|

Erin Endicott Sheldon, Healing Sutra#26, 2012, hand

embroidery on antique fabric stained with walnut ink |

In this way she relates who work to the many unknown artists who participated in a traditional arts of quilting. Like the Star of Bethlehem quilt now at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the traditional “Stitch” arts remind us to follow our stars while staying grounded in our traditions.

|

| Star of Bethlehem Quilt, 1830, Brooklyn Museum of Art Gift of Alice Bauer Frankenberg. Photo by Gavin Ashworth/Brooklyn Museum |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Jul 26, 2013 | Contemporary Art, Eco-Art, Environmental Art, Greater Reston Arts Center, Local Artists and Community Shows, Painting Techniques, Sculpture

|

| William Alburger, Forest, 2013, 65″ x 108″ x 9″ rescued spalted birch, in an solo exhibition at GRACE |

Eco-friendly art is meeting the world of high art, if we’re to take a cue from what’s showing at local art centers and galleries. It can be stated that the earliest environmental art started with the artists’ visions and applied those visions to the environment, with little interest in sustainability.

Quite the opposite trend is developing now. Several emerging artists, the “environmental artists” of the 21

st century put nature in the center–not the artist or the idea. Nature is the subject and the artist is nature’s follower. The following artists’ creations are about the land and earth; other artists interested in the environment have been more concerned with a world under

the sea.

|

William Alburger, Non-traditional Backwards

One-Door, 2012, 27″ x. 13.5″ x 5.25

reclaimed Pennsylvania barn wood, specialty

glass and fabric |

William Alburger lives in rural Pennsylvania, where he picks up scraps of wood from fallen trees and mixes them with discarded barn doors. He is a passionate conservationist with an addiction to collecting what otherwise would be burned, decayed or discarded in landfills. Largely self-taught, Alburger formerly worked as a painting contractor. His art is both pictorial and practical. Some sculptures almost look like two-dimensional works, while others function as shelves or furniture. Hidden doors, cubbyholes and cabinets create surprises, making the natural world his starting point for expression. Intrusions of man-made items are minor. The knots, whirls, colors and textures of wood speak for themselves, revealing rustic beauty.

|

William Alburger, Synapse, 2013,

65″ x 23″ x 5.25″ rescued spalted

poplar and Pennsylvania barn wood |

Currently the Greater Reston Area Arts Center (GRACE) is hosting a solo exhibition of Alburger’s works. In Synapse, Alburger cut into the interesting grain and patterns of fallen poplar. He framed top and bottom with old barn wood and reconfigured the form to suggest the space where two forms meet and form connection. Allburger finds what is already there in nature, but, through presentation, teaches us how to see it in a new way. Otherwise, we might not notice what nature can evoke and teach us.

|

Pam Rogers, Tertiary Education, 2012, handmade

soil, mineral and plant pigments, ink, watercolor

and graphite on paper. Courtesy Greater

Reston Area Art Association |

Dedication to the natural world is second nature to Pam Rogers, whose day job is as an illustrator in the Natural History Museum of the Smithsonian Institution. “I’m inclined to see environment as shaping all of us,” Rogers explains, noting the importance of where we come from, and how our natural surroundings mark our stories and connections. While drawing natural specimens, she sees as much beauty in decay is as in birth, growth and development. We’re reminded that everything that comes alive, by nature or made by man, will turn to dust. Rogers’ drawings combine plants, animals and occasional pieces of hardware. Some of the pigments spring from nature, the red soil of North Georgia and plant pigments.

As in Alburger’s Synapse, above, Rogers seeks to form connections between man and the environment. She inserts nails and other links into the drawings from nature for this purpose, as in Stolen Mythology, below. At the moment, Pam Rogers’ art is in the show, {Agri Interior} in the Wyatt Gallery at the Arlington Arts Center. One of her paintings is now in a group exhibition, Strictly Painting, at McLean Project for the Arts.

|

Pam Rogers, Stolen Mythology, 2009 mixed media

|

Rogers mixes traditional art techniques with abstraction, natural with man-made, sticks and strings, and does both delicate two-dimensional works and vigorous three-dimensional art. Her sculptures and installations explore some of the same themes. At the end of last year, she had an exhibition at GRACE called Cairns. Cairns refer to a Gaelic term to describe a man-made pile of stones that function as markers. Her work, whether two-dimensional or three-dimensional, is also about the markers signifying the connections in her journey.

|

| Pam Rogers, SCAD Installation (detail), plants, wire, metal fabric, 2009 |

“There are landmarks and guides that permeate my continuing journey and my exploration of the relationship between people, plants and place. I continually try to weave the strings of agriculture, myth and magic, healing and hurting.” Several of her paintings have titles referring to myths, including Stolen Mythology, above, and another one called Potomac Myths. Originally from Colorado, Rogers also lived in Massachusetts and studied in Savannah for her Masters in Fine Art. It’s not surprising that, in college, she had a double major in Anthropology and Art History.

|

Henrique Oliveira, Bololô, Wood, hardware, pigment

Site-specific installation, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution

Photograph by Franko Khoury, National Museum of African Art |

Artists cite the spiritual and mythic connection we have to environment. As a student, Brazilian artist Henrique Oliveira noted the beauty of wood fences which screened construction sites in São Paolo. Observing these strips being taken down, he collected them and re-used the weathered, deteriorating sheets of woods for some of his most interesting sculpture. Oliveira was asked to do an installation in dialogue with Sandile Zulu for the Museum of African Art in Washington, DC. His project, Bololô, refers to a Brazilian term for life’s twists and tangles, bololô. The weathered strips can act like strokes of the paint brush, with organic and painterly expression, reaching from ceiling to wall and around a pole but usually not touching the ground. Oliveira’s installation is a reflection of the difficulty in staying grounded in life, in this tangle of confusion.

|

Danielle Riede, Tropical Ring, 2012, temporary installation in the Museum of Merida, Mexico

photo courtesy of artist |

|

|

Environmental concerns played a part in the collaboration of Colombian artist Alberto Baraya and Danielle Riede, at the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art, shown in 2011. Expedition Bogotá-Indianapolis was “an examination of the aesthetics of place and its plants” in central Indiana. For two years, the artists collected artificial plants from second-hand stores, yard sales and neighborhoods in around Indianapolis. Last year Riede did an installation for the City Museum of Merida, Mexico, Tropical Ring. It’s made of artificial plants garnered from second-hand crafts in from Indiana and Mexico. The plants were cut and reconfigured to evoke the pattern of an ecosystem, indoors. Currently, the artist is looking for a community partner to participate in Sustainable Growths, an art installation of crafts and other re-used objects destined for abandoned homes in Indianapolis.

|

Danielle Riede, My Favorite Colors, 2006, photo courtesy

http://www.jardin-eco-culture.com/

|

|

|

|

Originally, Riede’s primary medium was discarded paint, which she gathered from the unused waste of other artists or the pealing pigments of dilapidated structures. My Favorite Colors, right, follows several paths of recycled paint along the wall of the Regional Museum of Contemporary art Serignan, France. Beauty comes from the color, light, pattern, and even from the shadows cast on walls to deliberate effect. The memory landscape is uniquely described in the eco-jardin-culture website. The installation is permanent, although much of what we consider environmental art is temporary.

|

Sustainable Growths: Painting with Recycled Materials is Riede’s

project to bring meaning to abandoned homes in Indianapolis. Artist’s photo |

Fallen trees, branches and other wastes of nature are tools of drawing to artist R L Croft. Some artists feel they have no choice but to re-use and re-claim discarded goods or fallen debris, as many folk artists and untrained artists have always been doing. The need to draw or create is innate and a constant in one’s identity as an artist, but it’s not easy to get commissions, jobs or sell art. Art materials are very expensive, so there is a practical objective to using environmental objects which do not need to be stored.

|

| R L Croft, Portal, 2011, Oregon Inlet, North Carolina |

To Croft, using the environment is a means of drawing, but on a very large scale. His outdoor, impromptu drawings-in-the-wild are images grounded in his style of painting and sculpture. Croft has made a number of sculptures called “portals” and/or “fences,” most of which have been carried away by rising tides or decay. He makes these assemblages out of debris found along the beaches, particularly those of the Outer Banks, in North Carolina. Portal at Oregon Inlet, NC, left, was constructed of found lumber, nails, driftwood, plastic, rope, bottles, netting, etc.

Environmentalism is not the primary content of his art. Croft says: “Making art for the purpose of being an environmentalist doesn’t interest me. Making art whose process is environmentally friendly does interest me.” He works in rivers, woods and on beaches. In the aftermath of one natural disaster, Hurricane Irene, he brought meaning to the incident–both personal and anthropological.

.jpg) |

R.L. Croft, Shipwreck Irene, in Rocky Mount, N.C. Built in October, 2012, it’s still there but

less recognizable as a ship form. The location is in Battle Park

off of Falls Road near the Route 64 overpass. Photo courtesy of artist.

|

Croft made Shipwreck Irene in Rocky Mountain, NC, when the Maria V. Howard Art Center held a sculpture competition and allowed him the use of fallen debris after Hurricane Irene, which left as much physical devastation as his sculptures allude to metaphorically. The shipwreck is a very old icon in the history of art, usually associated with 17th century Dutch seascapes. But to Croft, who in childhood found healing in the Outer Banks after the death of his mother, the meaning is deep. The area known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic” fed his early sense of adventure and aesthetic appreciation for texture, decay and the abrasive effects of wind, sand and water.

Hurricane Irene “is much like the resilient community frequently raked over by severe hurricanes, yet plunging forward. The current art center is world class and it is the replacement for an earlier one destroyed when still new. ” Croft said. Shipwreck Irene is still there, but decay renders it increasingly unrecognizable as a ship form. The temporary aspect is expected. “People of the region know grit and impermanence,” the artist explained. “I’m told that Shipwreck Irene became a habitat for small animals and small birds but that is a happy accident.”

|

| R L Croft, Sower, 2013, 22 x 14 courtesy artist |

|

Croft has also said: “Nothing can be taken for granted. Constant change proves to be the only reliable point of reference. Equilibrium being as fleeting as life itself, one fuses an array of thought fragments retrieved from memories into a drawing of graphite, metal or wood. By doing so, the artist builds a fragile mental world of metaphor that lends meaning to his largely unnoticed visit among the general population.” Croft did an installation in the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, a drawing in the wild entitled Sower, in homage to Van Gogh He worked in wattle to make a large drawing that, in a metaphorical, abstracted way, resembles a striding farmer sowing his seed. The farmer is the winged maple seed and it references Vincent’s wonderful ink line drawings.

Nature has been the subject of art by definition and a curiosity about the natural world has defined a majority of artists since the Renaissance. The first wave of Environmental Artists applied their vision to the environment by directly making changes to the environment–permanent (Robert Smithson, James Turrell) or temporary (Christo and Jeanne-Claude) Turrell ,whose most famous work is the Roden Crator in Arizona, is the subject of a major

retrospective now in New York, at the Guggenheim.

It is one thing for art to alter the environment, as the earliest environmental artists did. It is another thing to make art to call attention to the problems of waste and depletion of the earth’s resources. Yet, it’s an even stronger statement when professional artists exclusively make art that re-uses discarded items and turns them into art. Environmental Art today addresses waste reduction and stands up against the problems caused by environmental damage to our rapidly changing world. Designers are getting into this process, as explained in the previous blog. For example, Nani Marquina and Ariadna Miguel design and sell a rug made of discarded bicycle tubes, Bicicleta.

In the future, I hope to blog on how artists address sustainable agriculture. Currently, the main exhibition at Arlington Arts Center, Green Acres: Artists Farming Fields, Greenhouses and Abandoned Lots.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by admin | Jan 6, 2010 | Art and Science, Greater Reston Arts Center, Rebecca Kamen

Never having studied High School Chemistry, I am fascinated by how sculptor Rebecca Kamen has taken the elemental table to create a wondrous work of art. The beautiful floating universe of Divining Nature: The Elemental Garden–recently shown at Greater Reston Area Arts Center (GRACE)–is based on the formulas of 83 elements in chemistry. Its amazing that an artist can transform factual information into visual poetry with a lightweight, swirling rhythm of white flowers.

According to Kamen, who teaches art at Northern Virginia Community College in Alexandria, she had the inspiration upon returning home from Chile. After 2 years of research, study and contemplation, she built 3-dimensional flowers based upon the orbital patterns of each atom of all 83 elements in nature, using Mylar to form the petals and thin fiberglass rods to hold each flower together. The 83 flowers vary in size, with the simplest elements being smallest and the most complex appearing larger. The infinite variety of shapes is like the varieties possible in snowflakes; their whiteness and uniformity of material connect them, but individually they are quite different.

One could walk in the garden and feel a mystical sensation in the arrangement of flowers, as intriguing as the “floral arrangement” of each single element. After awhile I discovered that the atomic flowers were installed in a pattern based upon Fibonacci’s sequence. Medieval writer Leonardo Fibonacci and ancient Indian mathematicians had discovered the divine proportion present in nature. This mystical phenomenon explains the spirals we see in nature: the bottom of a pine cone, the spirals of shells and the interior of sunflowers among other things. Greeks also created this pattern in the “golden section” which defines the measured harmony of their architecture. Kamen wanted to replicate this beauty found in nature and enlisted the help of an architect, Alick Dearie, to create the 3-D spatial arrangement.

Kamen likened her flowers to the pagodas she had seen in Burma. However, there is an even more interesting, interdisciplinary connection. Research on the Internet brought Kamen to a musician, Susan Alexjander of Portland, OR, who composes music derived from Larmor Frequencies (radio waves)emitted from the nuclei of atoms and translated into tone. Alexjander collaborated, also, and her sound sequences were included with the installation. Putting music and art together with science mirrors the universe and it is pure pleasure to experience this mystery of creation.

This installation is now in storage, but hopefully it will be exhibited again during the International Year of Chemistry, 2011. In the meantime, there are few videos online that can be found on youtube searching the artist’s name.

.jpg)

Recent Comments