by Julie Schauer | Feb 1, 2014 | Exhibition Reviews, Fiber Arts, Folk Art Traditions, Greater Reston Arts Center, Local Artists and Community Shows, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Women Artists

|

Rania Hassan, Pensive I, II, III, 2009, oil, fiber, canvas, metal wood, Each piece

is 31″h x 12″w x 2-1/2″ It’s currently on view at Greater Reston Arts Center. |

There’s a revival of status and attention given to traditional, highly-skilled arts and crafts made of yarn, thread and materials. “Stitch,” a new show at Greater Reston Arts Center (GRACE), proves that traditional sewing arts are at the forefront of contemporary art, and that fiber is a forceful vehicle for expression. Meanwhile, the National Museum of Women in the Arts puts the historical spin on traditional women’s art in “Workt by Hand,” a collection of stunning quilts from the Brooklyn Museum which were shown in exhibition at their home museum last year.

|

Bars Quilt, ca. 1890, Pennsylvania; Cotton and wool, 83 x 82″;

Brooklyn Museum,

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. H. Peter Findlay, 77.122.3;

Photography by Gavin Ashworth,

2012 / Brooklyn Museum |

Quilts are normally very large and utilitarian in nature. To some historians, American quilts are appreciated as material culture with possible stories of the people who made them, but they also have some vivid abstract patterns and strong color harmonies. Their bold geometric shapes vary and change with different color combinations. Quilting is a folk art since it is a passed down tradition, and the patterns may seem stylized and highly decorative. Yet there is room for tremendous variation, creativity and individual style.

Within the United States there are important regional folk groups whose quilts have a distinctive style, like the Amish quilt, above. Amish designs can have a sophisticated abstraction deeply appreciated during the period of Minimal Art of the 1960s and 1970s. The exhibition outlines distinctions and also shows styles popular at certain times, including Mariners’ Knot quilts around 1840-1860, the Crazy Quilts of the Victorian period and the Double Wedding Ring pattern popular in the Midwest after World War I.

|

| Victoria Royall Broadhead, Tumbling Blocks quilt–detail, 1865-70 Gift of Mrs Richard Draper, Brooklyn Museum of Art. Photo by Gavin Ashworth/Brooklyn Museum. This silk/velvet creation won first place in contests at state fairs in St. Louis and Kansas City. |

, |

|

|

|

|

One beautifully patterned quilt is from Sweden, but the rest of them are made in the USA. The patterns change like an optical illusions when we move near to far, or when we view in real life or in reproduction. There’s the Maltese Cross pattern, Star of Bethlehem pattern, Log Cabin pattern, Basket pattern and Flying Geese pattern, to name a few. The same patterns can come out looking very differently, depending on the maker. An Album Quilt has the signatures of different people who worked on different squares. We know the names of a handful of the quilting artists.

|

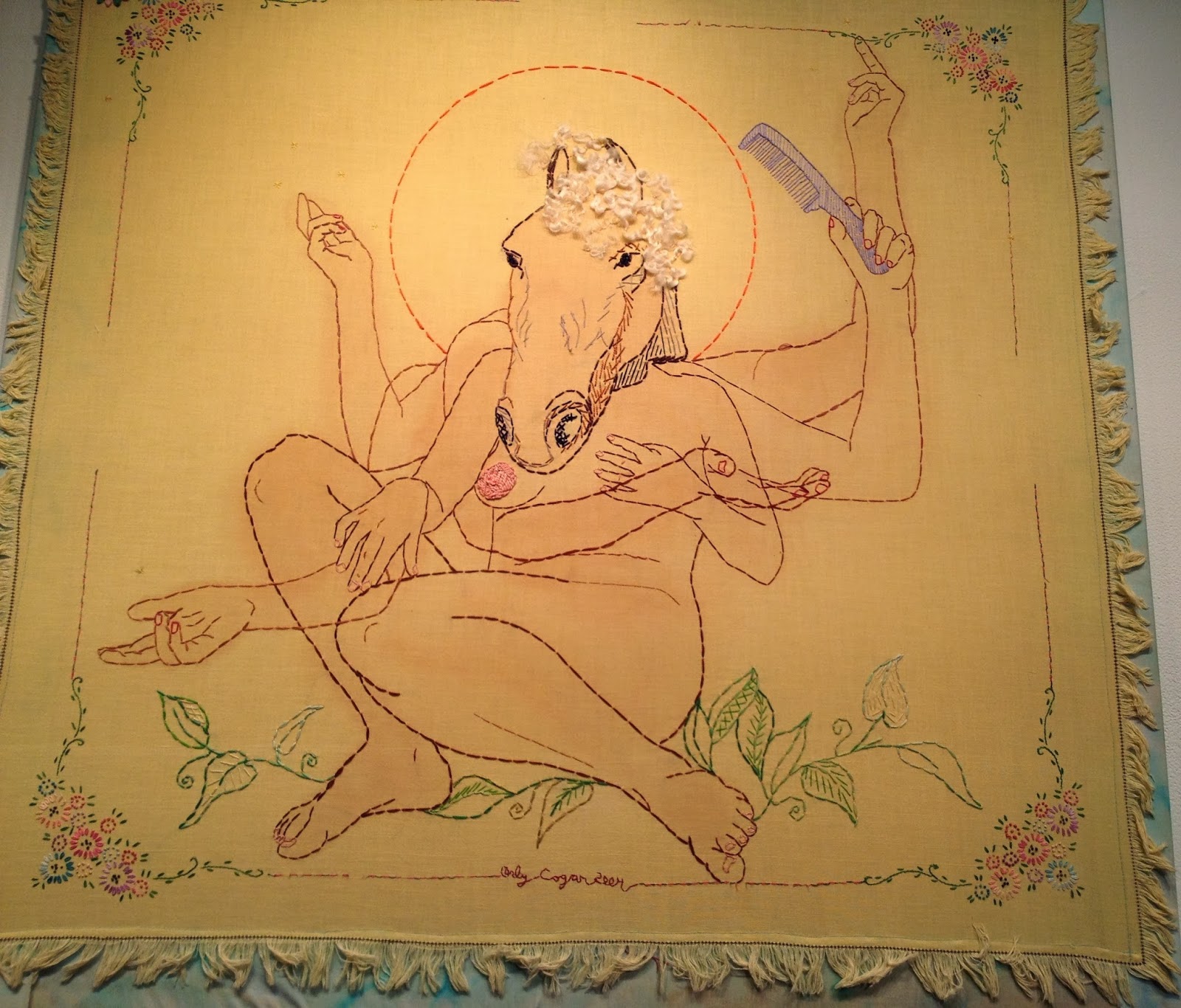

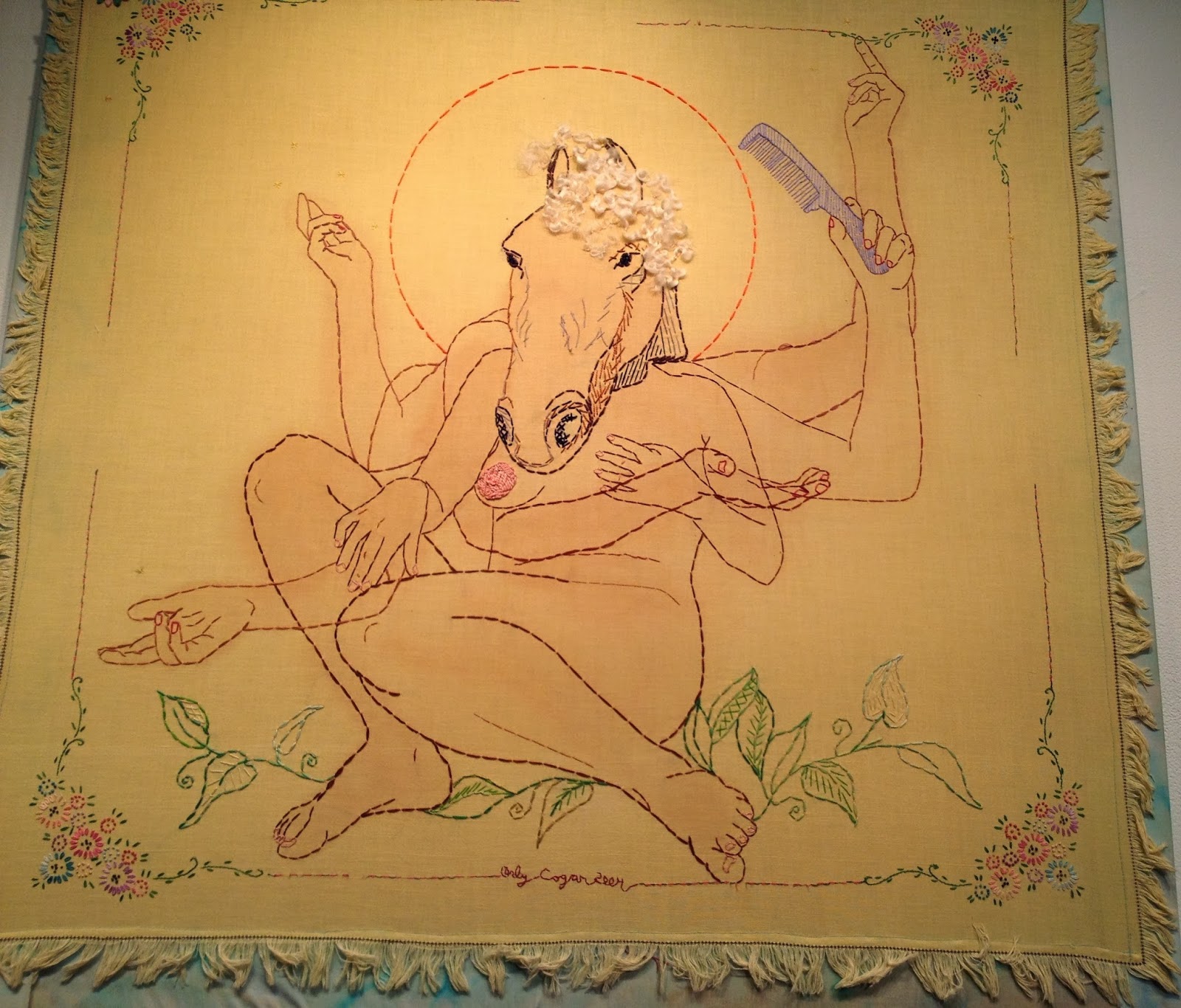

Orly Cogan, Sexy Beast, Hand stitched embroidery

and paint on vintage table cloth, 34″ x 34″ |

While most of the quilts featured in the exhibition were made by anonymous artists, the Reston exhibition includes well-known national figures in fiber art, such as Orly Cogan and Nathan Vincent. Cogan uses traditional techniques on vintage fabrics to explore contemporary femininity and relationships. Her works appear to be large-scale drawings in thread. She adds paint and sews into old tablecloths. I loved the beautiful Butterfly Song Diptich and Sexy Beast, a human-beast combination with multiple arms, like the god Shiva. Vincent, the only man in the show, works against the traditional gender role, crocheting objects of typically masculine themes, such as a slingshot.

|

Pam Rogers, Herbarium Study, 2013, Sewn leaves, handmade

soil and mineral pigments, graphite,

on cotton paper, 22″ x 13-1/2″ |

Most “Stitch” artists are local. Pam Rogers stitches the themes of people, place, nature and myth found in her other works. Kate Kretz, another local luminary of fiber art, embroiders in intricate detail, expressing feelings about motherhood, aging and even the art world.

Kretz’s own blog illuminates her work, including many of the pieces in “Stitch. The pictures there and the detailed photos on an embroidery blog display in sharper detail and explain some of her working methods.

Often she embroiders human hair into the designs and materials, connecting tangible bits of a self with an audience. Kretz explains, “One of the functions of art is to strip us bare, reminding us of the fragility common to every human being across continents and centuries.”

Kretz adds, “The objects that I make are an attempt to articulate this feeling of vulnerability.” Yet some of the works also make us laugh and chuckle, like Hag, a circle of gray hair, Unruly, and Une Femme d’Un Certain Age. Watch out for a dagger embroidered from those gray hairs!

|

Kate Kretz, Beauty of Your Breathing, 2013, Mothers hair from gestation

period embroidered on child’s garment, velvet, 20″ x 25″ x 1″ |

|

Suzi Fox, Organ II, 2014, Recycled

motor wire, canvas, embroidery hoop

12-1/2″ x 8″ x 1-1/2″ |

Kretz is certainly not the only artist who punches us with wit and irony, and/or human hair, into the seemingly delicate stitches. Stephanie Booth combines real hair fibers with photography, and her works relate well to the family history aspect alluded to in NMWA’s quilting exhibition. Rania Hassan is also a multimedia artist who brings together canvas paintings with knitted works. In Dream Catcher and the Pensive series of three, shown at top of this page, she alludes to the fact that knitting is a pensive, meditative act. She painted her own hands on canvases of Pensive I, II, III and Ktog, using the knitted parts to pull together the various parts of three-dimensional, sculptural constructions. She adds wire to the threads for stiffness, although the wires are indiscernible. Suzi Fox uses wire, also, but for delicate, three-dimensional embroideries of hearts, lungs and ribcages (right).

There’s an inside to all of us and an outside. Erin Edicott Sheldon reminds us that stitches are sutures, and she calls her works sutras. Stitches heal our wounds. “I use contemporary embroidery on antique fabric as a canvas to explore the common threads that bind countless generations of women.” Her “Healing Sutras” have a meditative quality, recalling the ancient Indian sutras, the threads that hold all things together.

|

Erin Endicott Sheldon, Healing Sutra#26, 2012, hand

embroidery on antique fabric stained with walnut ink |

In this way she relates who work to the many unknown artists who participated in a traditional arts of quilting. Like the Star of Bethlehem quilt now at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the traditional “Stitch” arts remind us to follow our stars while staying grounded in our traditions.

|

| Star of Bethlehem Quilt, 1830, Brooklyn Museum of Art Gift of Alice Bauer Frankenberg. Photo by Gavin Ashworth/Brooklyn Museum |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Jan 26, 2014 | Asian Art, Buddhism, Collage, Folk Art Traditions, Mandalas, Medieval Art, Mosaics, The Sackler Gallery of Art

|

Temporary floor mandala, flashed by light onto the floor

of the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery of Asian Art |

Mandalas, an important tradition in India, Nepal and Tibet have spread well into the West, or as some think, have always been in the West. The exhibition, Yoga: The Art of Transformation at the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery of Art, takes us into art and history surrounding the physical, spiritual and spiritual exercise of yoga. It’s the first exhibition of its kind. This is the last weekend of the show, featuring works of art in Hindu, Jain and Buddhist practice. Yoga hold some keys to mental and physical healing.

We’re led into yoga’s 3,000-year history by a series of light patterns flashed on the floor–patterns that are mandalas and have lotus patterns. (Lotus is also the name of a yoga pose.) After this weekend, they’ll be gone with the show, but that’s the spirit of mandalas, at least in the Tibetan tradition.

|

| Light Pattern on the floor of the Sackler Gallery of Asian Art forms a Mandala |

Mandalas have radial balance, because their designs flow radially from the center, somewhat like the spokes of a wheel. Traditional Buddhist monks in Tibet spend time together making mandalas of colored sand, working from the center outward using funnels of sand that form thin lines. Deities are invoked during this process of creation, following the same ancient pattern of 2,500 years. The creation is thought to have healing influence. Shortly after its completion, a sand mandala is poured into a river to spread its healing influence to the world.

|

| Chenrezig Sand Mandala was made for Great Britain’s House of Commons in honor of the Dalai Lama’s visit in May, 2008. Material: sand, Size: 7′ x 7′ Source of photo: Wikipedia |

|

|

|

Like the Buddhist Stupas which began in India, the Mandalas are microcosms of the macrocosm, or small replicas of the universe. Yantras are mandalas that are an Indian tradition which may have a more personal meaning. Their beautiful geometric designs can be highly efficient tools for contemplation, concentration and meditations. Concentrating on a focal point, outward chatter ceases and the mind empties to gain a window into truth. Making mandalas can be a powerful aid in Art Therapy.

|

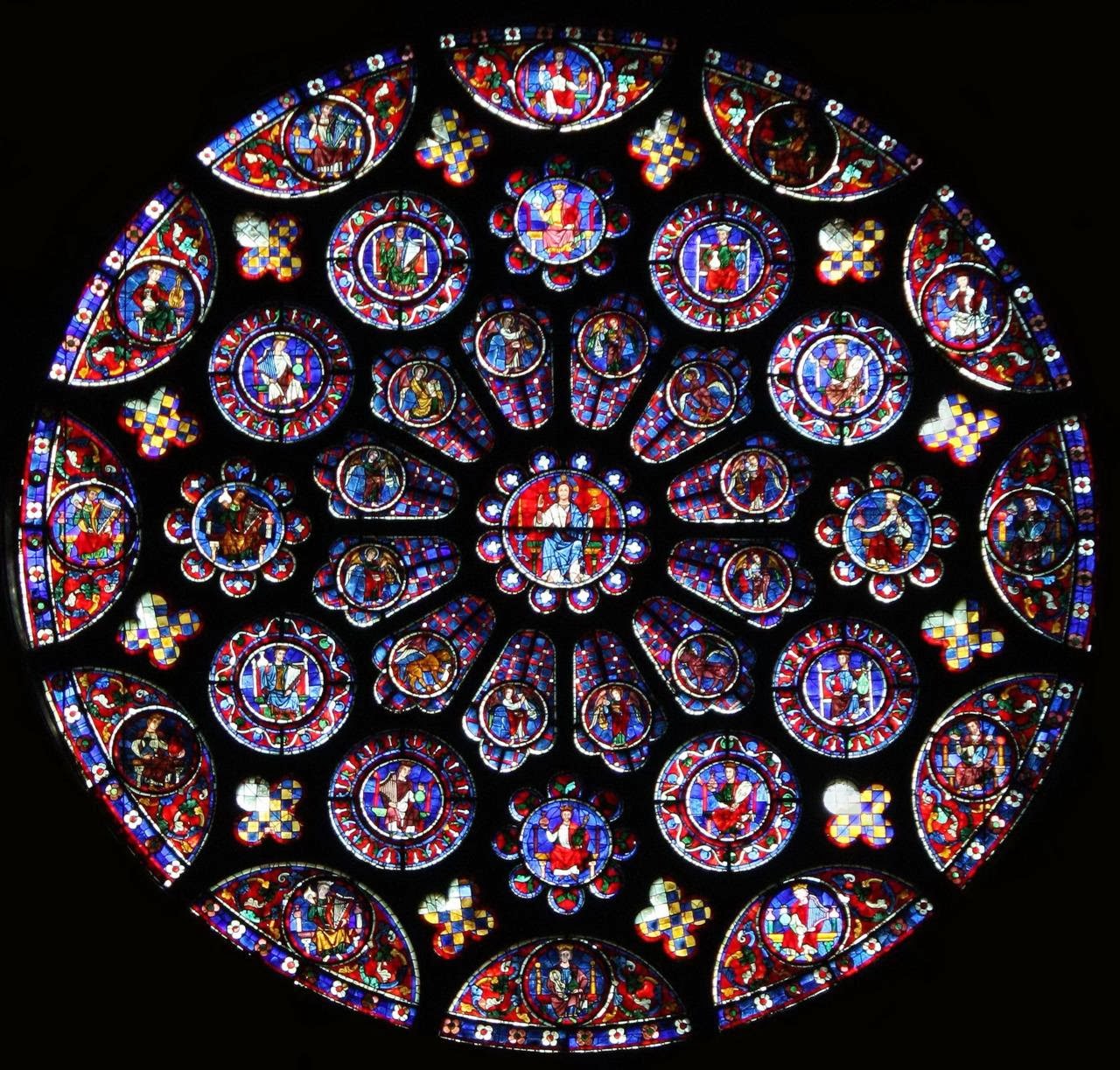

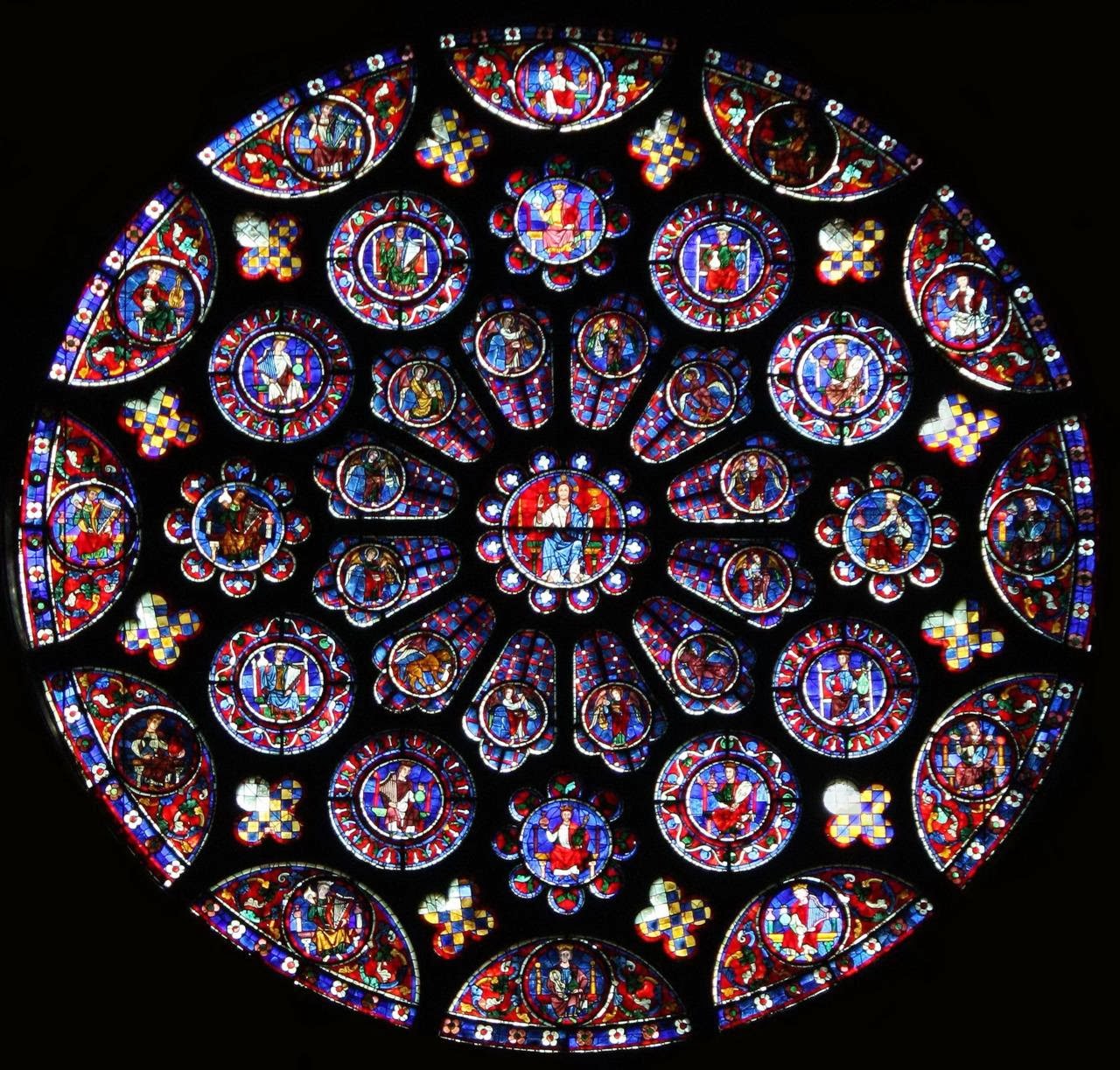

| North Rose Window of Chartres Cathedral, France, c. 1235 |

Circles, without a beginning or end, have an association with God and perfection. They’re an integral part of the design of Gothic Cathedrals, such as Chartres Cathedral and Notre-Dame of Paris which are among the most famous. Their patterns radiate out from the center, into rose patterns. I didn’t believe it when, years ago, a student mentioned they were inspired by Indian mandalas. The greater possibility is that spiritual wisdom comes from the same or similar sources.

|

Sri Chakra Mandala, ceramic tile, made by Ruth Frances Greenberg

17-1/4″ x 17-1/4″ x 1-1/4′ photo Lubosh Cech |

Artist Ruth Frances Greenberg makes ceramic tile mosaic mandalas in her Portland, Oregon studio, and sells them for personal and decorative use. Some are inspired by the Om symbol and by the home blessing doorway mandalas of Tibet. Others are inspired by the Chakras, the energy centers in ancient Indian tradition. The Sri Chakra Mandala has nine interlocking triangles and beautiful geometric complexity. It combines the basic geometric shapes of circle, square and triangle, and expresses powerful energies.

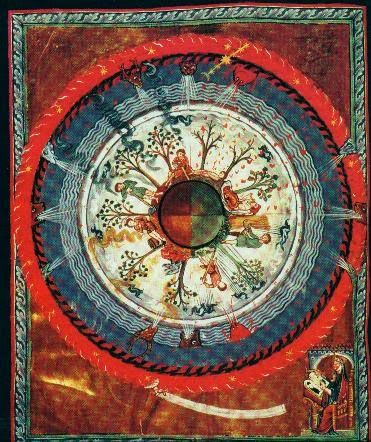

The circle within a square is common in many traditions, but in Indian art the openings of the square represent gateways. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, a study of perfection in human proportions, has a circle within a square. Medieval mystic, St. Hildegard of Bingen, a Doctor of Church, wrote music and created art in response to her visions. Wheel of Life is one of her many visions that were put into illumination in the mandala form, in the 12th century.

Chicago artist Allison Svoboda makes mandalas from a surprising combination of media: ink and collage. She explains, “The same way a plant grows following the path of least resistance, the quick gestures and simplicity of working with ink allows the law of least resistance to prevail….With this process, I work intuitively through thousands of brushstrokes creating hundreds of small paintings. I then collate the work…When I find compositions that intrigue me, I delve into the longer process of collage. Each viewer has his own experience as a new image emerges from the completed arrangement. The ephemeral quality of the paper and meditative aspect of the brushwork evoke a Buddhist mandala.”

|

| Allison Svoboda, Mandala, GRAM, 211–detail |

The 14′ by 14′ Mandala GRAM from the Grand Rapids Art Museum is a radial construction with many inner designs. Some of these designs resemble a Rorschach test, but infinitely more complicated.

The intricacies of the GRAM Mandala alternate and change as our eyes move around it. It’s like a kaleidoscope or spinning wheel. But a configuration in center pull us back in, reminding us to stay centered and whole, as the world changes around us.

|

| Allison Svoboda, Mandala, GRAM, 2011, Grand Rapids Museum of Art, in on paper, collaged 14′ x 14′ |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 22, 2013 | Art and Science, Encaustic, Environmental Art, Fiber Arts, Folk Art Traditions, Hyperbolic Coral Reef, Painting Techniques, Watercolor

|

| The Hyperbolic Coral Reef project has spread around the globe |

Nature is mysterious and some of the magical colors and patterns of the coral reef are a wonder of nature’s artistry. Surprisingly, vegetables such as kale, frissée and other lettuces mimic the free-flowing, wild patterns found in the coral reef. These products of nature form hyperbolic planes, not explained by Euclidean Geometry.

Crochet, a fiber art that traditionally has utilitarian purpose, holds the power to make this mystery visible to our eyes. With this in mind, various hyperbolic coral reef projects have sprung up around the globe, bringing together crochet artists to call attention to the fact that this natural wonder — something akin to the oceans’ natural forest — is vastly disappearing as a result of pollution, human waste and climate change.

|

| Photo of satellite reef, Föhr, Germany, courtesy Uta Lenk |

The Hyperbolic Coral Reef Project is the brainstorm of Margaret and Christine Wertheim, who founded the Institute for Figuring in Los Angeles to highlight this phenomenon. They based their idea on the discovery of a mathematician at Cornell University, Daina Taimina. Taimina used crochet to unlock a mathematical means to explain the parallel nature of crochet lines in 1997, while the Wertheims further developed a repetoire of reef-life forms: loopy “kelps”, fringed “anemones”, crenelated “sea slugs”, and curlicued “corals.” A simple pattern or algorithm, which has a pure shape can be changed slightly to produce variations and permutations of color and form. The Crochet Reef project began in 2005 and the experiment has involved communities of Reefers, which, like the reef itself, have become worldwide. The Wertheim sisters come from Australia, where the Great Barrier Reef is located, while Taimina is originally from Latvia.

|

| Photo of Actual Coral Reef, from www.thenowpass.com |

These handmade, collaborative works of fiber art have brought together art, science and math to a worldwide community — for the purpose of the sharing a wonder of nature that could be lost. The replica of a coral reef for the Smithsonian Community Reef was a satellite of the Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef Project installed at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in 2010-2011. This project has moved and is on view in the Putnam Museum of History and Natural Science in Davenport, Iowa, where it will remain for 5 years. A former student, Jennifer Lindsay supervised the installation and the public outreach at the Smithsonian and the Putman and is currently coordinating the Artisphere Yarn Bomb in Arlington, Va.

|

| Postcard from the coral reef project in Föhr, Germany |

This past summer, there was an installation at the Museum Kunst der Westkuste on island of Föhr, in Germany. Over 700 artists from the island, and the mainland of Germany and Denmark came together and contributed to the largest of over 20 worldwide projects around the world. At this moment, there is a satellite of the Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef Project at Roanoke College in Salem, Va. It will remain there at the Olin Gallery until March 1, 2013, reminding students at this Liberal Arts College of the fragility of the coral reef.

Artist Elise Richman — who lives on the Puget Sound and teaches at the University of the Puget Sound in Tacoma, Wa — also reminds us that changes are afloat at sea. Richman has different processes of painting, each of which reflect environmental systems and states of flux. In the water-based paintings, she applies inks, acrylics and a liquified powder pigment that has been mixed with powder gum arabic. She pours pools of these paints onto thick sheets of watercolor paper, allowing them to expand, evaporate, be absorbed or intermingle, while using minimum control.

|

| Elise Richman, Each Form Overflows its Present, mixed media on canvas, 2013, photo by Richard Nicol |

The poured paint dries into forms that evoke the contours of islands, water bodies, and/or fluid dynamics. Richman then takes these contours as boundaries that she can transgress in subsequent layers. “I assert my will by deepening the color, adjusting the quality of particular edges and unifying the compositions while maintaining the dynamic sense of flux that the materials activate,” she explains.

More recently, she has used this technique on large-scale canvases. Her newest water-based paintings, such as Each Form Overflows its Present, I, represent an active state of flux as well as topographical formations. They comment, through implication, on the threat of accelerated changes humans have induced on the environment.

|

| Elise Richman, Isle I, oil, 12 x 12, 2008 photo by Richard Nicol |

Richman also has a body of three-dimensional oil paintings made of organic dots which seem to grown from the canvases. As one moves around the small, intricately-detailed paintings, the topographies and colors change in visually dynamic ways, maintaining their aesthetic beauty. These forms represent non-hierarchical environments. “They evoke tide-pools of miniature islands; intimate marine scapes act as

|

| Elise Richman, detail of Pool I, 2010, photo by Richard Nicol |

meditations on the processes of painting, an embodiment of time’s passage, and models of the material world’s interconnectedness,” Richman explained. Each mark, point or dot has its own integrity, yet each is subsumed into a larger whole that has an ethical as well as aesthetic dimension. In short, imbalances of power create exploitations of the natural world and groups of people. Yet this largeness of nature can be maintained in works of art that are personal and meditative. Richman’s website includes works in the encaustic and acrylic paint media. The encaustics have multiple layers, from which she scrapes to represent geological formations.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Dec 5, 2012 | Contemporary Art, Exhibition Reviews, Fiber Arts, Folk Art Traditions, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Women Artists

|

| Photo courtesy of Rachael Matthews from the UK Crafts Council |

“High fiber” usually refers to a type of diet, but High Fiber at the National Museum for Women in the Arts demonstrates how “high art” integrates with the everyday world of a Folk Art. In the multi-media world of contemporary art, Fiber Art has gained recognition as a serious art form over the last fifty years. Like the art of glass making, fiber art was invented milleniums ago for utilitarian purposes. Knitting, sewing and weaving developed to meet basic needs of warmth and clothing, but as soon as pattern and design were involved, the process of making art began.

|

| Knitted objects are often in Matthews’ work |

When the ancient artists/crafters knitted, knotted, wove or stitched to follow patterns or innate designs in their heads, they tied together movements between the left and right hands, bridging the creative left side of the brain with the analytical right side of the brain.

Contemporary fiber art may or may not have definite recognizable patterns and designs, but fiber art by definition is very tactile and textural. It may also be sculptural.

The National Museum for Women in the Arts’ exhibition of contemporary fiber artists, on view until January 6, 2013, features seven contemporary fiber artists, each working in styles completely different from the next one. High Fiber is the third installment of NMWA biennial Women to Watch exhibition series, in which regional outreach committees of the museum meet with local curators to find artists. The NMWA made a final selection of the seven artists representing different states and countries.

Rachael Matthews was a leader in a revival of knitting movement in the UK about 10 years ago. She is co-owner of a knit shop in London, Prick Your Finger, where one is more likely to see objects crafted of yarn, rather than a sweater. In Knitted Seascape, 2004, Matthews used illusionism much the way painters do; her hanging curtains, lace-like and pleated, open onto the seascape seen through a false window. She created depth similar to that in Raphael’s visionary painting. The vigorous texture into those waves, making their foam as real as in a Winslow Homer seascape, is not painted but knitted. Matthews also did a floor sculpture to which an hourglass and skull and crossbones attach. We are reminded of death in A Meeting Place for a Sacrifice to the Ultimate Plan, 2010. Another piece she supplied in the exhibition is a wedding dress, made as a collaborative effort where the individual pieces knit by different women form the whole. Collaboration and connection is certainly a part of emerging trend in Fiber Art.

Louise Halsey, from the Arkansas council, is a weaver, who has spent years studying the ancient art of weaving, while teaching and doing workshops. Her work demonstrates vivid color and technical perfection, but also shares the artist’s own narrative ideas. The four works in this show are images of homes. On her website, she explains, “Recently I have been weaving tapestries using the house as a symbol for what I cherish. These images of houses include placing the house amidst what I see as threats that are present in the environment.” Dream Facade, at right, may warn of being too strongly possessed and owned by vanity, while Supersize My House, 2011, questions the dream of bigger and bigger homes.

Louise Halsey, Dream Facade, 2005

wool weft on linen warf – tapestry technique

The house becomes sculpture in large, colorful constructions by Laure Tixier, from France and representing Les amis du NMWA, are based on architecture from around the world. Like children’s forts out of blankets, architecture meets the basic need for shelter with imagination in design. She stitches the forms out of felt and very large Plaid House reflects the classical architecture of Amsterdam. Smaller houses are also on display and they reveal her domestic interpretations of diverse types of architecture, including that of the future. Tixier clearly has an interest in the symbolism and meaning of architecture in history.

Laure Tixier’s Plaid House , 2008, wool felt and thread, 90-1/2″ x 33-1/2″

Collection of Mudam Luxembourg

Debra Folz of Boston combines sophisticated cross-stitch patterns on furniture and mirrors with a sleek modern look. Her works are a contrast to the homespun beauty of some of the works described above, but she was trained in Interior Design. The threads are small and look mechanical but can have depth, control, color harmony and pattern. Mixing thread with a industrial materials may sound discordant, but this harmony of opposites is beauty!

Debra Folz, XStitch Stool, 2009. Steel base,

perforated steel and nylon thread, 20 x 14 x 12 in

Steel is the canvas for embroidery.

|

| Beili Liu, Toil, 2008, Silk organza,72 x 36 x 8 in |

Homes and their contents give security and comfort, but not all works of art in the exhibition have a domestic meaning. There are sculptural wall hangings and installations in the NMWA’s show. Beili Liu, recommended by the Texas State committee, spun strips of silk, a material traditionally associated with China, her country of origin. For Toil, she burned the edges of silk fabric with incense before winding the strips into the funnel-shaped projections that point off the wall. These forms twist and turn in various directions — like miniature tornadoes — creating paths and shadows on the wall. A variety of beige and brown tones add to the richness of this view. Liu’s larger Lure Series (not on view) installations use thread to recall Chinese folklore, she has that is said her work highlights the tensions between her Eastern origins and Western influences. She bridges these gaps well. In fact, fiber art is all about connecting.

Fiber Art seems to be on the verge of asserting new importance into the world of art. Jennifer Lindsay, one of my former students from the Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art and Design’s Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts, coordinated the public outreach, the design and collaborative installation of the Smithsonian Community Reef. The replica of a coral reef in crochet made expressly for the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s 2010-2011

expressly for the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s 2010-2011 Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef project, is now on view in the Putman Museum of History and Natural Science in Davenport, Iowa, until 2016.

|

| Jennifer Lindsay, Cowgirl Jacket is a memento mori to Frida Kahlo, photo by Judy Licht |

Jennifer also dyes her own wool yarns and uses them to make intricate knitted and crocheted clothing, examples of which are shown here. She calls her cowgirl jacket a memento mori for Frida Kahlo. It uses nearly every knitting stitch available. Note the skeletons which link this design to El Dia de los Muertos. Memento mori is a reminder of death.

|

| Lindsay’s Russian Star, photo by Judy Licht |

Getting back to the women’s museum, in the permanent collection, there are other works of fiber or those that remind us of fiber. On the 3rd floor of the NMWA, Remedios Varo’s Weaving of Space and Time is on loan along with two other works by Varo. The oil on masonite painting uses a symbolic circle to magically pull together the opposites of male and female figures, representing time and space. Within the circle are threads, not real threads but painted threads in light glazes that weave together ideas. Nearby is also a Judy Chicago painting whose circular painted form in acrylic and airbrush resembles the type of patterning with which traditional fiber artist created.

NMWA also has a piece by Magdalena Abakanowicz, one of the best known fiber artists of today. Four Seated Figures are of her recognizable life-size figural types made of fabric. The same, yet different, these abakans are representative the anonymity and uniformity of communist society in Poland, what she has known during the bulk of her life. Born in 1929, to Abakanowicz is accustomed to living in conditions which repressed individual creativity and intellect in favor of the collective interest.

|

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Four Seated Figures, 1974-2002, burlap, resin, metal pedestal

figure: 115 cm, 55 cm, 63 cm pedestal: 76 cm, 47 cm, 23 cm

coll. The National Museum of Women in the Arts |

Finally, we can be reminded of the diverse women came together for their quilt-making art who in a film of 1995 called How to Make An American Quilt, including Maya Angelou, Anne Bancroft, Ellen Burstyn, Alfre Woodard and Winona Ryder. Quilting is one the most lasting forms of Fiber Art, embedded into so many folk art traditions. In the end, the making of a quilt is compared to life: “As Anna says about making a quilt, you have to choose your combination carefully. The right choices will enhance your quilt. The wrong choices will dull the colors, hide their original beauty. There are no rules you can follow. You have to go by your instinct. And you have to be brave.”

It’s with fibers that women can connect and that the women of history are tied to the women of today.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments