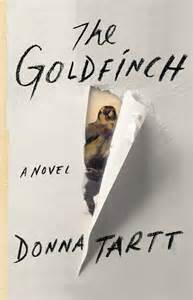

The Goldfinch: Truth in Art and Life

|

| Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch, 1654 |

“We have art in order to not die for the truth.” Donna Tartt quotes Nietzche in the opening of one of her chapters in The Goldfinch, an epic journey of life novel. It’s taken me all year, but finally, I’ve finished reading The Goldfinch (need a long plane trip to do that). The entire drama is centered around a missing painting, or, shall we say, a stolen painting in the hands of the narrator.

It’s interesting that Donna Tartt chose a painting to be the symbol of her protagonist. Carel Fabritius’ The Goldfinch — the painting — is a bird chained on a pedestal. He’s stationary–as if saying “I am.” At one point, the author gives a hint of original purpose for the painting, that it was a signpost for a tavern. (That’s the type of things art historians write about, but Tartt writes about the painting in a much more interesting way.)

Because I’m not a literary scholar, I can’t comment on Tartt’s writing. But as an art critic, she understands why we need art in our lives. The quotes in the book are full of wisdom about the intersection of art and humankind, art and life, truth and life. She understands art as well as any art historian. Here are some quotes from the book:

“If our secrets define us as opposed to the face we show the world: then painting was the secret that raised me above the surface of life and enabled me to know who I am.”

The voice in the book, Theo Decker, starts when he’s a 13-year old. His life is a traumatic one, and he soon becomes an orphan.

The voice in the book, Theo Decker, starts when he’s a 13-year old. His life is a traumatic one, and he soon becomes an orphan.

“If every great painting is really a self-portrait what if anything is Fabritius saying about himself?” (Here’s the other blog I wrote about birds by multiple artists.)

She describes qualities the goldfinch has that are like human qualities: “It’s hard not to see the human in the finch. Dignified, vulnerable. One prisoner looking at another.” Later on Tartt writes: “… even a child can see its dignity: thimble of bravery, all fluff and brittle bone. Not timid, not even hopeless, but steady and holding it’s place. Refusing to pull back from the world.”

Before coming to this conclusion, the protagonist makes these smart observations about life:

“Can’t good sometimes come from strange back doors?”

“Coincidence is God’s way of remaining anonymous.”

As Theo goes through so many trials and tribulations, we think that it’ll end in tragedy and that he’ll be doomed. Of Theo’s relationship to Pippa, the narrator says: “Since our flaws and weaknesses were so much the same, and one of us could bring the other one down way too quick.” It seems this truth is often the case in many relationships. Kitsey, to whom Theo is engaged, seems quite the opposite of Theo in so many ways, shallow and disengaged. Do such opposites anchor each other and keep them from going to deeply in the wrong direction? (The answer, well, is that his transformation comes without her in the picture)

Tartt also makes us think about beauty and truth.

“Beauty alters the grain of reality.”

“It’s not about outward appearances but inward significance.” The narrator explains at the end that the “only truths that matter are the ones I don’t, and I can’t, understand.” So what does the painting mean for him? “Patch of sunlight on a yellow wall. The loneliness that separate every living creature from every other living creature,” This description can be applied to the goldfinch, and how Theo sees his life.

“There’s no truth beyond illusion. Because between reality on the one hand, the where the mind strikes reality, there’s a middle zone, a rainbow edge where beauty comes into being, where two very different surfaces mingle and blur to provide what life does not; and this is the space where all art exists, and all magic.”

On p. 569, Horst describes the Fabritius painting: “It’s a joke….and that’s what all the very greatest masters do. Rembrandt, Velazquez. Late Titian…..They build up the illusion, the trick–but step closer? it falls apart into brushstrokes. Abstract, unearthly. A different and much deeper sort of beauty altogether. The thing and yet not the thing.” “There’s a doubleness. You see the mark, you see the paint for the paint, and also the living bird.” “He takes the image apart very deliberately to show us how he painted it. Daubs and patches, very shaped and handworked, the neckline especially, a solid piece of paint, very abstract.” What lovely descriptions of the intersection of realism and abstraction.

Why is The Goldfinch so touching to so many people, both the book and the painting? Theo and Tartt express deep appreciation for the restoration specialists, like Hobie, Theo’s caretaker and business partner. Hobie lovingly bring works back to their original state. In the book, there’s an intersection between truth and illusion, but there’s also the understanding that great art is at once realistic and abstract.

The Goldfinch is a trompe l’oiel painting, but it is so much more.

“Its the slide of transubstantiation where paint is paint and yet also feather and bone. It’s the place where reality becomes serious and anything serious is a joke. The magic point where every idea and it’s opposite are equally true.” As I often say, art is about the reconciliation of opposites, and Theo and Tartt achieve this in The Goldfinch.

In Dutch art history, Fabritius, a pupil of Rembrandt stands in between his teacher and the master of Delft, Vermeer. Vermeer’s simplicity could not be imagined without The Goldfinch, and one wonders if he was in fact Vermeer’s teacher. Fabritius lived in Delft at the time of his death in in 1654. He died in a gunpowder explosion when he was only 32. Gerry, a blogger in Great Britain, did a tremendous job of explaining Fabritius and his painting.

I always enjoy reading books that center around a painting. But this novel is not about how or why the painting was made. It is about the journey of the painting and it’s presumed caretaker, what it does for him through his growing years and into several years of adulthood. It is a symbol of his life, his hopes and the man he became.

Recent Comments