Van Gogh: Touched by Fire and Pain

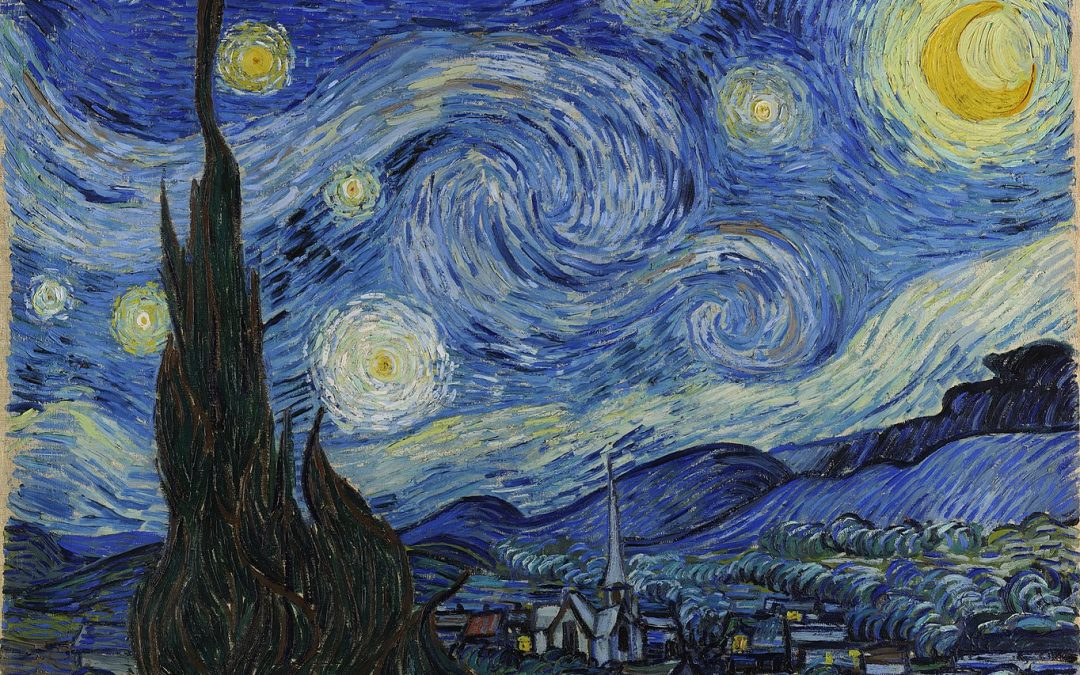

When people think of Vincent Van Gogh’s visionary art, the first painting that comes to mind is A Starry Night, 1889, the painting memorialized by Don McLean’s song. Everyone knows he lived a tortured life, ending it by suicide at age 37.

My two great passions, art and mental health, come together in Van Gogh. I recently finished reading The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence, by British art historian Martin Gayford. The book chronicles Van Gogh’s life in the Fall of 1888, letters to his brother and others, his relationship with Paul Gauguin and Gauguin’s letters (This period was also the subject of an excellent, ground-breaking exhibition organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, about 20 years ago.)

Questions linger:

The Bedroom at Arles, 1888, The Art Institute of Chicago

Did his art arise because of his illness or in spite of his illness?

Were his most productive works done during periods of intense mania?

Did his unique vision come from certain hallucinations?

Or was it produced in the depths of despair?

Although van Gogh sold only one painting during his lifetime, other artists like Gauguin and Émile Bernard easily recognized his genius. His brother, Theo, also his art dealer, displayed kindness towards him, always supporting him financially. When Van Gogh began as a painter, about 10 years before his death, he had already failed in other professions. By the time he shared the “Yellow House” with Gauguin in Arles, some of Gauguin’s paintings had already been sold. Van Gogh was more prolific than Gauguin, but he hadn’t sold a thing. It is not unusual for an artist to face rejection and still persevere, so we can’t pin his mental state on the problem of rejection. Fortunately, he described his works in detail in letters to his brother.

Gayford checks out the evidence in his paintings against the evidence in letters, his life events, Gauguin’s letters and historical records. To my surprise, the book describes Gauguin as particularly patient with his housemate, despite the weird behaviors.

What happened between Van Gogh and Gauguin?

Van Gogh moved to Arles early in the year of 1888, but Gauguin didn’t arrive until October. Van Gogh had a head start, and he already knew the neighbors, people like the Ginouxs, innkeepers; the Roulins, the postmaster, his wife and children, and the grocer next door. Both men frequented bars and prostitutes, but Gauguin didn’t drink much. Vincent had the dream of starting an art colony there.

To see what may have led to the final incident, one should look at the painting Van Gogh was working on at the time of the falling out. “La Berceuse,” meaning the woman who rocks the cradle” is a portrait of Madame Roulin, whom he painted at least five times. According to Gayford, Pierre Loti’s book about Icelandic fishermen inspired this painting.

Van Gogh imagines the lady as a Madonna-like figure, rocking the cradle which is held by a string and stands outside of the painting. How very strange, but both Van Gogh and Gauguin were inspired by Symbolist poetry, and symbolism is definitely the intent here. Colors need not reflect visual reality, but can express feeling. Here, complementary colors of red and green, which appear opposite each other on the color wheel, set the tone. Except for the lady’s enormous bosom, the painting appears flat, The hands are jagged and crooked. Madame Roulin gave birth to her third son a few months earlier. The string of the cradle may allude to this fact, but she looks detached from it. Van Gogh was a very literary man, but what was he thinking?

La Berceuse is not a good bedtime story, but it had a great deal of influence on later art such as that of Matisse. It is one of five versions he made in December 1888 and finished in January 1889.

On December 22, Gauguin wrote a long letter describing to a friend his challenges with Van Gogh, but claimed that he would stay. After supper on December 23, Gauguin left the yellow house and Van Gogh followed after him, blade in hand. Although Gauguin’s own accounts vary, he would never return. In response, Vincent cut off the lower part of his ear that night and bled profusely. He enclosed the ear, delivered it to a brothel, and marked it for a woman named Rachel, saying “Guard this object carefully.” He returned home and went to sleep. (Kirk Douglas plays Van Gogh in A Lust for Life, acting out these events.)

Postmaster Roulin nursed him back to health and his family was informed. At this time, according to Gayford, p. 228, his mother wrote to Theo, “I believe he was always ill and his suffering and ours was a result of it.”

What do we know of his mental illness in light of today’s knowledge?

Van Gogh was known to have a form of epilepsy, but it wasn’t his primary problem. He drank heavily and people found him especially strange and scary when he was drunk.

Because Van Gogh cut off his ear, some people believe he had auditory hallucinations. Most often hallucinations are associated with psychosis. Psychosis that is permanent generally refers to schizophrenia. It can take the form of visual or auditory hallucinations. Those who support the schizophrenia diagnosis believe he was trying to stop auditory hallucinations. However, that hypothesis doesn’t explain why he cut off only part of his ear and why he delivered it to Rachel. The message intended for Rachel, as well as the meaning of La Berceuse, would make sense to him, but not the outside world.

In the 1800s mental illnesses were not classified as they are today, but we would see his highs and lows as most characteristic of Bipolar I. Gayford firmly argues this position, saying that Van Gogh had hallucinations and made associations that didn’t fit with reality. Vincent identified emotionally with Hugo van der Goes, a gifted 15th-century Netherlandish painter who also had a fit of madness and attempted to kill himself.

It’s true that many creative people who touch us deeply are also touched by a fire within. Writers Edgar Alan Poe and Ernest Hemingway are often named as other great geniuses who suffered from Bipolar Disorder. They also drank heavily and ended their lives tragically. The “unruly genius,” Caravaggio, certainly belongs in this category, too. The Romantic tradition of the early 1800s celebrated an affinity between madness and creativity, as with Goya and Beethoven, both of whom became deaf and deeply depressed as they aged. (I have not read Kay Redfield Jamison’s book about this, Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament. My sources at the end of this article.)

Contrary to popular belief, those who suffered from mental illnesses in the 1880s — at least where Van Gogh lived — were not treated poorly. Cold bath therapy rather than heavy pharmaceuticals, were the treatments of his day. And Van Gogh’s doctors respected him; they wanted him to paint.

Timeline and Treatment, 1889

Van Gogh recovered quickly and he completed La Berceuse in January.

January 5 – Dr. Félix Rey came to see him. According to the doctor, Vincent spent much time explaining his paintings to the doctor. He continued La Berceuse around this time.

On February 3, he wrote to his brother Theo: “I have moments when I am twisted with enthusiasm or madness or prophesy…”

February 7 – He was back in the hospital in Arles with a new doctor. Dr. Deloy wrote that Van Gogh was in a state of overexcitement and spoke in incoherent words. He thought people were trying to poison him.

February 17 – He had recovered. But in the meantime, the inhabitants of Arles petitioned the mayor to have him sent away, either to his family or to an asylum. Thirty residents signed the petition, naming him a public nuisance. Women and children were scared of him, and one dressmaker claimed he grabbed her. They complained of his excessive drinking.

March 23 – Painter Paul Signac came to visit him and suggested he move to Cassis, a port on the Mediterranean

May 3 – He voluntarily entered the Saint-Paul de Mausole Asylum in Saint-Rémy, thirteen miles from Arles. The building, a monastery from the 11th century, is open to the public today. He was treated well here under the care of Dr. Peyron. He was encouraged to paint and produced some of his best-known works here, including A Starry Night, Irises and many views of fields and cypress trees.

June – Van Gogh wrote to his brother: “This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star which looked very big.” He painted A Starry Night during this period but regretted it: “once again I allowed myself to be led astray into reaching or stars that are too big — another failure — and have had my fill of that.”

He continued working at the asylum for the rest of the year. While not allowed to drink at all, he was very productive.

Timeline and Treatment, 1890

January 16 – He was in an important exhibition in Brussels and received a good review

In the first four months of the year, he had several attacks and spent most of the time in a state of withdrawal.

May 16 – He left Saint-Rémy, and was taken under the care of a homeopathic doctor, Dr. Paul Gachet and went to see his brother in Paris.

May 19 – He moved to a small village outside of Paris, Auvers-sur-Oise, under the care of Dr. Gachet.

June 8 – He had a reunion with his brother, Theo. Dr. Gachet pronounced him cured.

Early July — The darkness returns again.

July 27 – He shot himself in the chest but survived. (Recent accounts suggest that he was killed by others, a view suggested in the movie, At Eternity’s Gate, 2019.)

July 29 – He died at 1:30 a.m.

Vincent’s Artistic Output Seen Against His Illness

Many artists take time to reach greatness, to find their inner self or their best artistic expression. That was the case with Vincent. The paintings we most admire today were done in 1888, 1889, and 1890, while he was in Arles and Saint-Rémy. Works for this period are more unified, more visionary and hold together well. It is easy to see that he finally found his style in the South of France, even if it was where his madness emerged most profoundly.

As for producing art during periods of mania, we must look into his years of output. In his short lifetime, he wrote, 2,140 letters and created more than 3,000 works of art, 860 of them oil paintings. He averaged 96 paintings per year, compared with Monet who averaged 42, Cézanne who averaged 23, and Rembrandt who averaged 15. Each of the other artists was fanatical, as intense and driven as Van Gogh. Artists of their caliber, like Van Gogh, responded to a deep inner necessity, a “calling,” which could not be ignored.

(I thank Russ Ramsey, for the following information, the source listed on bottom, pp 138-141):

Van Gogh: Number of paintings per year:

1881- 2, 1882 – 14, 1883 – 18, 1884 – 52

1885 – 143, 1886 – 93, 1887 – 118

1888 – 169, 1889 – 134, 1890 – 108

How did he keep up this frenetic pace? Was he in manic phases when he did the most work? I believe so. He did 42 paintings in June 1990, the month before he died. During the first four months of 1890, he painted only 18 canvasses. Remember he had several episodes during this time, and I would assume they were deep, crippling depressions. Bipolar I is known for periods of intense highs and lows. When he was high, he could channel the energy into painting. When he was very, very low he couldn’t work at all.

Another sign of mania is in the brushstrokes, In his time, only Vincent Van Gogh used single strokes loaded heavily with paint, never mixing or blending. His paint was extraordinarily thick and heavy. There’s no room for error with this method, or the errors are part of the painting. No wonder he worked so quickly. When his genius was at its height, the texture of his paint mimicked the actual texture of the subject, as in his beard from the Self-Portrait, above, or in his Sunflowers, below.

Judging Him by the Standards of Today

I had wondered if drinking absinthe, legal at that time, had something to do with Vincent’s hallucinations and mood swings. Gayford refutes this notion. Today much mental illness is brought out by substance abuse, a problem that can be prevented. That probably not the case of Van Gogh, whose sister Jo was diagnosed with schizophrenia. In fact four of six children in the Van Gogh family appear to have suffered from mental illnesses of varying degrees. He may have used alcohol and absinthe to self-medicate. There exists a notion that drug use can enhance creativity, which may or may not be true. Even Baudelaire, who experimented with hashish in the 19th century, denied the idea that it was helpful for anything.

Would Van Gogh have done such incredible work if he had been medicated, as would be suggested today? Some people with Bipolar I refuse to take medications because they like the manias and don’t appreciate the flattening of moods. I think that in Van Gogh’s case, he could have lived longer with today’s medications, but he would not have lived as long in the hearts of future generations.

Sources:

Martin Gayford, The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence

Russ Ramsey, Rembrandt is in the Wind: Learning to Love Art Through the Eyes of Faith

Ingo F Walther and Rainer Metzger, Van Gogh: The Complete Paintings

Martin Bailey, The Sunflowers are Mine

I don’t pretend to have expertise on Bipolar I Disorder, but I’ve read Kay Redfield Jamison, An Unquiet Mind, and Terry Cheney ‘s Mania. Robert Whitaker’s Mad in America confirms the belief that treatments of the mentally ill in 19th century France were not lacking compassion and were often better than the treatments of today.

We must thank Van Gogh for all his letters, for the artists and the sister-in-law, Jo, who saved his work. His letters are widely translated; and’ a new volume was published this year, The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh. Martin Bailey wrote a book explaining about Van Gogh at Saint-Rémy, Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum.

My other blogs about Van Gogh:

This one includes a photo from his asylum window and works he did in Auvers: https://artventures2.wpenginepowered.com/into-the-fields-with-van-gogh/

Torrents of Rain and Gusts of Wind

https://artventures2.wpenginepowered.com/the-gift-of-van-gogh-and-the-power-of-expressionism/

Recent Comments