by Julie Schauer | Mar 23, 2014 | 19th Century Art, American Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Art Institute of Chicago

|

| Abbot Handerson Thayer, Winged Figure, 1889, The Art Institute of Chicago |

It may be the dreamer in me who is so attracted to the winged paintings of Abbott Handerson Thayer. The first of his paintings that I fell in love with was Winged Figure. above, at the Art Institute of Chicago. I’ve always admired the loose simplicity of the Grecian style of clothes, even before studying Greek art. However, what appeals most to me is the sense of security and peace this figure has as she sleeps, protected and held by the curve of her wing. Her leg and golden garment are strong and sculptural, but it’s not clear if she’s on the ground or on a cloud.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Angel, 1887, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of John Gellatly Mary, the artist’s daughter, posed. |

After moving to Washington, I found that Thayer is represented well in the nation’s capital. Angel of 1887 is a very young figure, and Thayer’s daughter Mary served as the model when she was 11. She’s frontal, symmetric, quite pale and white. She may or may not be in flight. Thayer is probably the premier American painter of angels, a Fra Angelico or a Luca della Robbia in paint. He gives them an idealized beauty and paints in a pristine Neoclassical style, as well as Europeans did.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, A Winged Figure, 1904-1913, The Freer Gallery of Art,

Smithsonian Institution Gift of Charles Lang Freer. The model is the

artist’s daughter, Gladys |

One of the winged figures at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art wears a laurel wreath. More rigid than his other angels, she faces us frontally with the geometry of a Greek column. Her face is severe, too, and she doesn’t quite touch the ground. Daughter Gladys was his model. (The Freer Gallery of the Smithsonian has published an explanation of the Winged Figures collected by Charles Lang Freer.)

Thayer’s preference for painting winged figures was not entirely religious. His interest in naturalism started as a 6-year old living near Keene, New Hampshire, when he began the avid study of birds and nature. However, his obsession with painting winged figures, angels and innocent children may have something to do with the fact that two of his children died unexpectedly in the early 1880s. That so many of his figures gained wings may represent hopes he had for coming to terms with loss.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Virgin, 1892-93,

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution Gift of Charles Lang Freer

(The artist’s children, Gladys, Mary, Gerald) |

|

|

|

|

He painted his three remaining children over and over again, and three of these paintings are in the

Smithsonian American Art Museum. In

Virgin at the Freer Gallery of Art, the oldest Mary faces us frontally walking in a pose similar to the

Nike of Samothrace. Although she doesn’t technically have wings like the Nike of Samothrace, the clouds behind her become large, white wings. Mary is an icon in the center who boldly holds and leads the younger sister and brother. She is noble and unflappable but moves swiftly. The younger children are strong, too, and do not smile. Their hair flies in the wind and the ground they walk on is hazy. Above all, they’re innocent. (These two younger children, Gladys and Gerald, also became painters.)

Understandingly, there was some intense melancholy surrounding he and his wife for some time. In 1891, his wife died, too. Thayer may be sentimental, but the paintings of his children would suggest he wanted them to be strong, triumphant and prepared for any event.

|

| Abbott Handerson Thayer, Roses, 1890, oil on canvas 22 1/4 x 31 3/8 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly |

Thayer was a superb painter of other subjects. He also did portraits, landscapes and still lives, which can be found on the Smithsonian’s website. An exceptional still life at Smithsonian American Art Museum, Roses, demonstrates his incredible skill. He manages to be highly detailed with the leaves and blooms but spontaneous and expressive for the vase and background. The color is somewhat muted, but the texture is strong. The style of his still lives compares well to Edouard Manet’s textured still lives and the pristine beauty Henri Fantin-Latour’s still lives. Like the highly skilled academic painter Bouguereau, he seems to be able to combine the best of the great 19th century styles: Neoclassicism, Realism and the emotional or dreamy qualities of Romanticism.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Mount Monadnock, 1911, 22 3/16 x. 24 3/16 “

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC |

The other great style of the period was Impressionism, which captured the fleeting qualities of light and colors. While Thayer may not be categorized as an Impressionist, he should be added to the list of marvelous snow painters. His best scenes of snow come from the area near where he lived in Keene and in Dublin, New Hampshire. In the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s Mount Monadnock, 1911, Thayer captured some of the beautiful scenery surrounding this mountain very familiar to him. There are vivid blues, purples and reds in this snow and the lights on the mountain top are brilliant. There’s a small, horizontal string of light coming across the ground to separate trees from mountain.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Monadnock No. 2, 1912,

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution. Gift of Charles Lang Freer |

He repeated the composition over and over, as Impressionists did. Mount Monadnock, 1904 and Monadnock No. 2, 1912 are in the Freer Gallery of Art. The snow topped mountain is also brilliant and even whiter in the painting of 1912. Touches purplish-gray suggest how cold it must have been. The trees are dark however, a definite force of nature. Thayer knew Impressionistic techniques and had lived in France, but he was also an artist who wanted to find some solidity and permanence in the world, even as it will change and be gone. He painted Winter Dawn on Monadnock in 1918, now in the Freer, too. There were less pine trees at this time, but the radiant pinks of dawn pervade the scene on the left.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Winter Dawn on Monadnock, 1918, The Freer Gallery of Art,

Smithsonian Institution Gift of Charles Lang Freer. |

Who can see and understand illusion in nature better than an artist? In 1909, he and his son, Gerald Handerson Thayer, wrote a major book on protective coloration in nature, Concealing and Coloration in the Animal Kingdom: An Exposition of the Laws of Disguise. He ascertained that in shadow birds or animals become darker to be hidden, but naturally turn lighter in sun. Another naturalist, former President Teddy Roosevelt, scoffed at his ideas and they were not accepted. However, he tried to share his ideas with the American government during World War I.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Stevenson Memorial, 1903, 81-7/16 x 16 1/8 “

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC Gift of John Gellatly |

Thayer made as a memorial, above, to author Robert Louis Stevenson, someone he deeply admired but did not know. His first idea was for the memorial was to paint his three children, in honor of Stevenson’s book,

A Child’s Garden of Verses. He changed his mind, and a winged figure sits on a stone marked VAEA, the spot in Samoa where Stevenson is buried.

Thayer memorialized Stevenson, but what about his salvation? In 2008, the Smithsonian did a documentary film about him, Invisible: Abbott Thayer and the Art of Camouflage. Apparently his ideas about camouflage are more readily accepted now than they were in his time. Doesn’t his reputation as a painter deserve wide recognition, too? While keeping a foothold here on earth, his winged figures suggest that humans have the potential to transcend the hard life and fly above our limitations.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 8, 2010 | 19th Century Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Exhibition Reviews, Japanese Art, Jean-Francois Millet, Landscape Painting, Painting Techniques, Van Gogh

Jean-Francois Millet, The Gust of Wind, 1871-73, National Museum of Wales

Jean-Francois Millet, The Gust of Wind, 1871-73, National Museum of WalesIt’s disappointing that the Corcoran exhibition, From Turner to Cezanne, had to be taken down early as a precaution over environmental concerns……I was counting on going Friday, April 9, three days after it abruptly closed. What am I missing? A spectacular collection from the National Gallery of Wales, little-known paintings of well-known artists that are seldom seen in the US………………… Torrents of Rain and Gusts of Wind…..

Vincent Van Gogh, Rain, Auvers, 1890, from the National Museum of Wales

Vincent Van Gogh’s suns, stars and flowers from sunny Provence express the intensity he experienced while living there. But in May, 1890, he moved north of Paris to Auvers-sur-Oise and painted Rain, Auvers in July. Van Gogh used such a heavy impasto of paint that this painting conveys a heavy impact of rain. Van Gogh had an uncommon ability to combine actual texture of the paint itself with the tangible, tactile sense of objects painted. I really wanted to see Rain, Auvers to experience the downpour. Exaggerated or not, Van Gogh has the power to create a reality that makes us feel its presence more keenly. But the rain in this painting, deliberate gashes to the canvas surface, warns of a downpour more powerful than rain, the artist’s impending doom–he shot himself July 29th.

Even more than the Van Gogh, I was also looking forward to seeing paintings by Daumier and Millet, two mid-19th century French painters who are often overlooked, particularly in their gifts of great draftsmanship. Van Gogh seems to have admired them. One of Millet’s paintings from this Davies Collection at the National Museum of Wales is The Gus t of Wind, 1871-73. Millet conveys the full fury of a storm in the countryside. He captures the birds, leaves and branches with jagged, undulating brushstrokes. Along with the wind, his tree is uprooted and the birds, man (a shepherd whose sheep can barely be seen) and flock scatter in a fury, as the luminous colors of daylight poke through the background.

t of Wind, 1871-73. Millet conveys the full fury of a storm in the countryside. He captures the birds, leaves and branches with jagged, undulating brushstrokes. Along with the wind, his tree is uprooted and the birds, man (a shepherd whose sheep can barely be seen) and flock scatter in a fury, as the luminous colors of daylight poke through the background.

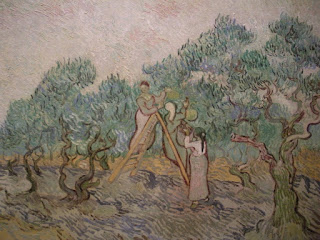

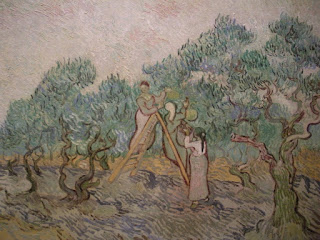

It is commonly understood that Van Gogh’s paintings of The Sower were inspired by Millet’s The Sower. No doubt Van Gogh knew many paintings by Millet and shared his appreciation for man’s connection to the land. He adopted Millet’s expressive lines, but thickened the contours and turned up the volume on color. Brandon, one of my students, was amazed to discover the wind that Van Gogh captured in The Olive Orchard, now on view in the Chester Dale Collection at the National Gallery of Art. Certainly Millet was one of Van Gogh’s most inspiring teachers, along with the Japanese artist Hiroshige, whose woodcuts gave Van Gogh the motif of diagonal cuts for rain.

In May and during

most of the summer, this exhibition travels to Albuquerque Museum of Art in New Mexico. However, while the O’Keeffe exhibition remains at the Phillips until May 9th, its worth seeing the weather photographs of Alfred Stieglitz and comparing them to paintings about weather.

Ando Hiroshige, Rain Shower on Ohashi Bridge, 1857woodcut, at the Library of Congress. The rain, treated like gashes in the wood, influenced the gashes in “Rain,Auvers”

Van Gogh, The Olive Orchard, 1889, Chester Dale Collection,N ational Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

ational Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

detail, The Gust

of Wind, shows

how Millet’s lines influenced Van Gogh

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments