by admin | Apr 20, 2012 | 19th Century Art, Hokusai, Printmaking

Some of Henri Riviere’s “36 Views of the Eiffel Tower.” are in the Phillips’ exhibition, Snapshot: Paintings and Photography, from Bonnard to Vuillard. Five Metro stops away, the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery is hosting an exhibition of Katsushika Hokusai’s “36 Views of Mt. Fuji.” The Cherry Blossom Festival just celebrated the100th anniversary of Japan’s gift of cherry trees to Washington, DC, a capital city based on French urban design patterns. These exhibitions coincided with that event.

Some of Henri Riviere’s “36 Views of the Eiffel Tower.” are in the Phillips’ exhibition, Snapshot: Paintings and Photography, from Bonnard to Vuillard. Five Metro stops away, the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery is hosting an exhibition of Katsushika Hokusai’s “36 Views of Mt. Fuji.” The Cherry Blossom Festival just celebrated the100th anniversary of Japan’s gift of cherry trees to Washington, DC, a capital city based on French urban design patterns. These exhibitions coincided with that event.

The top of the Eiffel Tower seen beyond the leaves is from Henri Riviere’s 36 Views of the Eiffel Tower, its Frontispiece,

published in 1902. Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mt. Fuji, 1830-1832, inspired him. The scene below, Mt. Fuji

from Goten-yama has Spring cherry blossoms opening to a distant view of the peak.

The Sackler exhibition has selected the most vivid images available of Hokusai’s woodblock prints and the colors are vibrant. Blues predominate, but most prints have at least 4 other hues. Riviere’s images are printed as color lithographs with more neutral color harmonies. French artists admired Japanese woodblock prints and Riviere owned at least 800 of them. The Phillips’ exhibition–definitely worth the visit–also has small paintings and many photographs by Post-Impressionist artists such as Edouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, George Hendrik Breitner, Henri Evenepoel and Felix Valloton.

Both artists create different atmospheric effects, including the effects of wind, snow and various cloud formations. In many prints by each artist, the subjects, Mt. Fuji or the Eiffel Tower, are subordinated to other scenery. Yet, Riviere used Hokusai’s examples as inspiration rather than imitation.

Through rooftops and chimneys of Paris’ many buildings we vaguely see the Eiffel Tower. A cat pokes through the diagonal zigzag of lines in the foreground as a dog runs away. Their silhouettes remind me

that Riviere did shadow plays for

Le Chat Noir (the Black Cat).

Warehouses line a canal to form diagonal lines which lead first, to Edo Castle, then to Mt. Fuji, on the upper left corner, (No 31 – Nihonbashi at Edo)

A large Mt. Fuji dominates the upper left, as a strong wind blows. In this Autumn view, the people look

small compared to the force of the wind (No. 18 – Sunshū Ejiri, in Suruga Province). Both

Hokusai and Riviere take the viewers through a yearly cycle of changing

weather conditions. Hokusai’s work dates to 1830-32.

Riviere also creates the sensation of Autumn wind surrounding a lonely man on a park bench. The

Eiffel Tower stands directly above him.

Riviere spent a year watching the building of the Eiffel Tower. During that time, he was able to go up into the construction and take photographs from the inside out. Twelve of these photos are in the Phillips’

exhibition, along with the lithograph above based on one of those pictures

The Phillips’ exhibition compares these prints to photographs Riviere shot of workers constructing the Eiffel Tower. Riviere’s primary profession was as a theatre set designer for Le Chat Noir, where he created shadow plays. As an artist, he is less well-known than Hokusai, although there is something magical about his style, perhaps a reflection of his work with silhouettes in the theatre and with photography. His prints were published in 1902 several years after he had taken the pictures of the Eiffel Tower.

Hokusai is one of Japan’s greatest artists. There are two more exhibitions of paintings and screens by Hokusai in the Freer Gallery of Asian Art, which holds the world’s largest collection of Hokusai and is attached to the Sackler Gallery. The rarely-seen Boy Viewing Mt. Fuji, ink on silk, is in a medium too fragile for continuous display, but it is included with the Hokusai paintings.

It is an interesting to see that Hokusai, as an eastern artist, identifies with the power of pure nature, a volcanic mountain which dominates the Japanese landscape, while the western artist’s symbol is a man-made construction, built for the World’s Fair of 1889 and still a dominant symbol of Paris today.

Hokusai’s Boy Viewing Mt. Fuji, 1846, is a peaceful painting which expresses the grandeur of Mt. Fuji in color and ink on silk. It is part of the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Asian art and will be on view until June 24, 2012 .

by admin | Apr 8, 2010 | 19th Century Art, Hokusai, Landscape Painting, Nature, Printmaking, Van Gogh

Jean-Francois Millet, The Gust of Wind, 1871-73, National Museum of Wales

Jean-Francois Millet, The Gust of Wind, 1871-73, National Museum of WalesIt’s disappointing that the Corcoran exhibition, From Turner to Cezanne, had to be taken down early as a precaution over environmental concerns……I was counting on going Friday, April 9, three days after it abruptly closed. What am I missing? A spectacular collection from the National Gallery of Wales, little-known paintings of well-known artists that are seldom seen in the US………………… Torrents of Rain and Gusts of Wind…..

Vincent Van Gogh, Rain, Auvers, 1890, from the National Museum of Wales

Vincent Van Gogh’s suns, stars and flowers from sunny Provence express the intensity he experienced in the South of France. But in May, 1890, he moved north of Paris to Auvers-sur-Oise and painted Rain, Auvers in July. This painting conveys a heavy impact of rain with Van Gogh’s uncommon ability to combine actual texture of the paint itself with the tangible, tactile sense of objects painted. I really wanted to see Rain, Auvers to experience the downpour. Exaggerated or not, Van Gogh has the power to create a reality that makes us feel its presence more keenly. But the rain in this painting, deliberate gashes to the canvas surface, warns of a downpour more powerful than rain, the artist’s impending doom–he shot himself July 29th.

Even more than the Van Gogh, I was also looking forward to seeing paintings by Daumier and Millet, two mid-19th century French painters who are often overlooked, particularly in their gifts of great draftsmanship. Van Gogh seems to have admired them. One of Millet’s paintings from this Davies Collection at the National Museum of Wales is The Gus t of Wind, 1871-73. Millet conveys the full fury of a storm in the countryside. He captures the birds, leaves and branches with jagged, undulating brushstrokes. Along with the wind, his tree is uprooted and the birds, man (a shepherd whose sheep can barely be seen) and flock scatter in a fury, as the luminous colors of daylight poke through the background.

t of Wind, 1871-73. Millet conveys the full fury of a storm in the countryside. He captures the birds, leaves and branches with jagged, undulating brushstrokes. Along with the wind, his tree is uprooted and the birds, man (a shepherd whose sheep can barely be seen) and flock scatter in a fury, as the luminous colors of daylight poke through the background.

It is commonly understood that Van Gogh’s paintings of The Sower were inspired by Millet’s The Sower. No doubt Van Gogh knew many paintings by Millet and shared his appreciation for man’s connection to the land. He adopted Millet’s expressive lines, but thickened the contours and turned up the volume on color. Brandon, one of my students, was amazed to discover the wind that Van Gogh captured in The Olive Orchard, now on view in the Chester Dale Collection at the National Gallery of Art. Certainly Millet was one of Van Gogh’s most inspiring teachers, along with the Japanese artist Hiroshige, whose woodcuts gave Van Gogh the motif of diagonal cuts for rain.

In May and during

most of the summer, this exhibition travels to Albuquerque Museum of Art in New Mexico. However, while the O’Keeffe exhibition remains at the Phillips until May 9th, its worth seeing the weather photographs of Alfred Stieglitz and comparing them to paintings about weather.

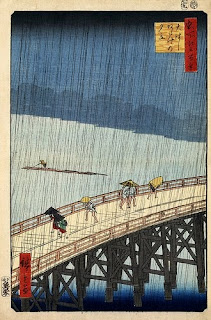

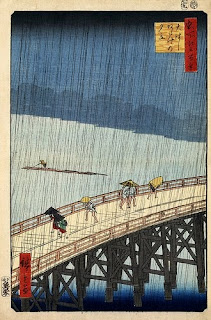

Ando Hiroshige, Rain Shower on Ohashi Bridge, 1857woodcut, at the Library of Congress. The rain, treated like gashes in the wood, influenced the gashes in “Rain,Auvers”

Van Gogh, The Olive Orchard, 1889, Chester Dale Collection,N ational Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

ational Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

detail, The Gust

of Wind, shows

how Millet’s lines influenced Van Gogh

Some of Henri Riviere’s “36 Views of the Eiffel Tower.” are in the Phillips’ exhibition, Snapshot: Paintings and Photography, from Bonnard to Vuillard. Five Metro stops away, the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery is hosting an exhibition of Katsushika Hokusai’s “36 Views of Mt. Fuji.” The Cherry Blossom Festival just celebrated the100th anniversary of Japan’s gift of cherry trees to Washington, DC, a capital city based on French urban design patterns. These exhibitions coincided with that event.

Some of Henri Riviere’s “36 Views of the Eiffel Tower.” are in the Phillips’ exhibition, Snapshot: Paintings and Photography, from Bonnard to Vuillard. Five Metro stops away, the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery is hosting an exhibition of Katsushika Hokusai’s “36 Views of Mt. Fuji.” The Cherry Blossom Festival just celebrated the100th anniversary of Japan’s gift of cherry trees to Washington, DC, a capital city based on French urban design patterns. These exhibitions coincided with that event.

Recent Comments