The Floor Scrapers and the Making of a Caillebotte Masterpiece

|

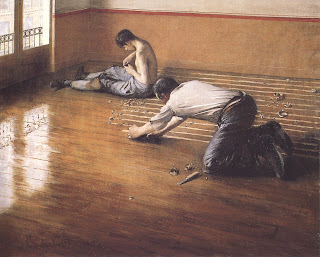

| Gustave Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers, 1875 Musée d’Orsay, now on view at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, |

Right now the National Gallery is having an exhibition of an Impressionist whose reputation has grown over the last 25 years, Gustave Caillebotte. Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye will be on view until October 4.

Caillebotte’s first masterpiece, The Floor Scrapers, was rejected by the Salon in 1875, but accepted into the Impressionist group exhibition the next year. He repaid his dear friends by buying up many of their works and then donating them to the French state after he died. Today many of those paintings belong to Paris’ great early modern museum, Musée d’Orsay.

There are so many reasons The Floor Scrapers is my favorite work by Caillebotte. The composition is extraordinarily well balanced with artful asymmetry on a tilted floor plane. (The invention of photography encouraged artists to look through the viewfinder and frame pictures differently.) There’s also the dignity given to labor, the working man and his beautiful anatomy.

Most it’s incredible to see how Caillebotte painted tactile contrasts on wood in the various stages of sanding, what looks like with or without varnish, and in the light and shadow. Caillebotte painted with more definition and precision than other Impressionists. Yet he illuminates the floor with natural light from the window and we see a wonderful scintillating values, colors and textures. Yellow shines through with touches of blue, but in the distance everything becomes an earthy brown color.

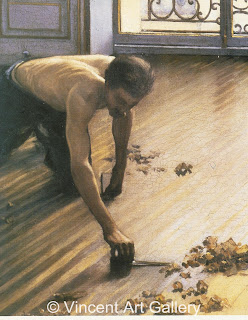

Caillebotte painted another floor scrapers

To understand how good this painting actually is, it’s useful to compare it with another version of floor scrapers that he did. It’s a simpler composition from a different angle, with fantastic lighting effects. Enlarging the photo here will really show off the reflections on the floor. (It isn’t in the National Gallery’s show, but was also part of the 2nd Impressionist exhibition in 1876.)

|

| Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers |

Many of Caillebotte’s other paintings in the exhibition also convey his artful sense of perspective: Le Pont de l’Europe, 1876, for example. He lived at the time that Paris had just experienced a massive rebuilding campaign of boulevards. Paris, A Rainy Day gives an impressive viewpoint of how the new city must have looked to the public, in the eyes of a new bourgeoisie class. Since streets corners were set up in star patterns, the linear perspective goes very deep into multiple vanishing points. A more famous artist, Georges Seurat, borrowed from the composition of Paris: A Rainy Day when he did his iconic painting of Paris on a sunny day, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte.

Other artists of the same time

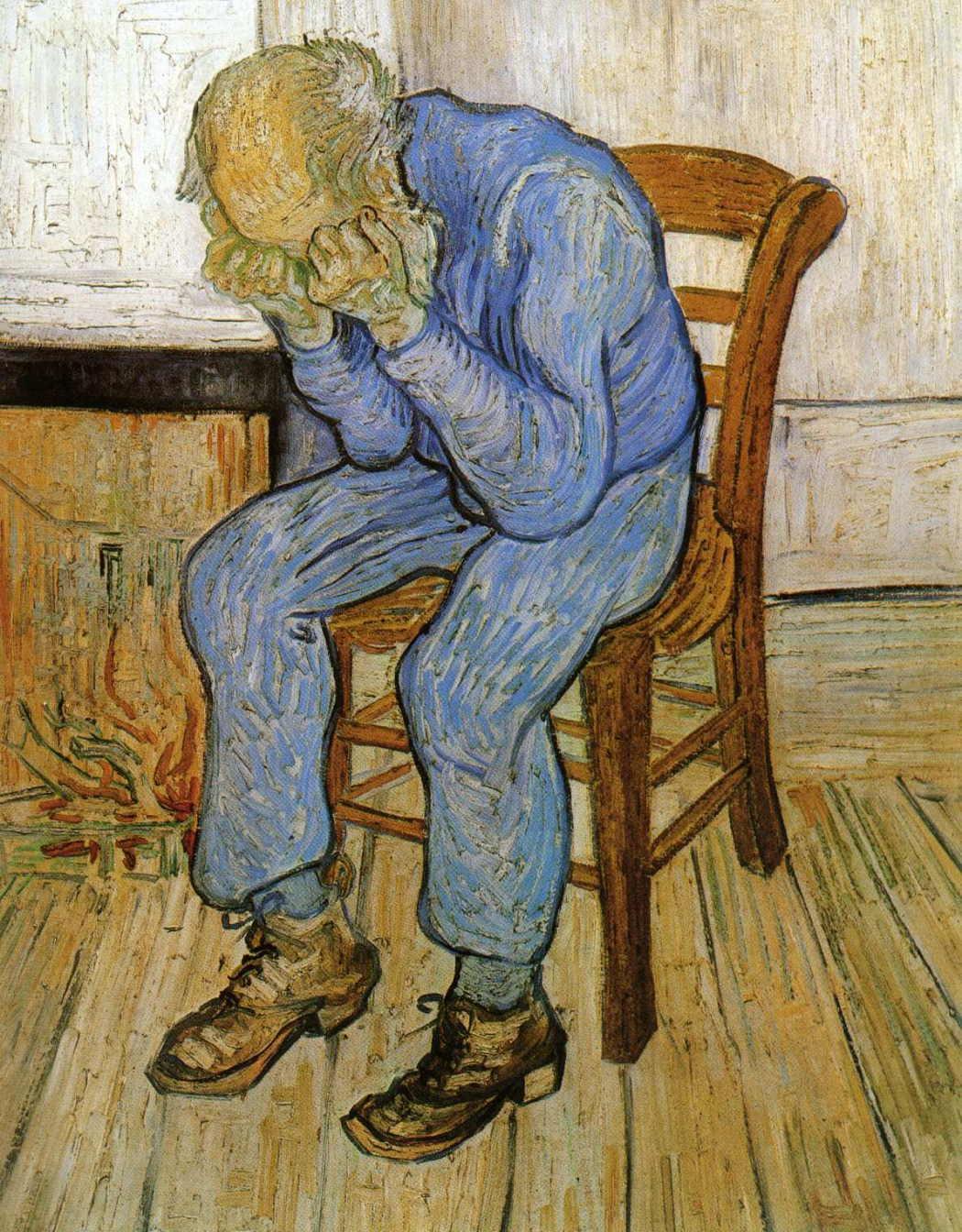

Monet and Van Gogh are other who shared Caillebotte’s love of deep perspective space. Degas went even further than Caillebotte to exploit the unusual viewpoint. His work can be seen in an important Impressionist exhibition is in Philadelphia, Discovering the Impressionists, until September 13. The exhibit showcases Paul Durand-Ruel, the art dealer who took a gamble and went into great financial risk by buying up Impressionist painters because he believed in them. The exhibit includes Monet’s beautiful Poplars series. However, one of the really important works in the group is by Degas, The Dance Foyer at the Opera on the rue Le Peletier.

|

| Edgar Degas, The Dance Foyer at the the Opera on the rue Le Peletier, 1872, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, now on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art |

Comparing Caillebotte’s Men to Degas’ Dancers

This panoramic ballet scene of dancers offers a wonderful comparison with the Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers. This painting is also asymmetric and appears to look spontaneous, while it is actually exceptionally well-planned. Degas offers more layers of observation: into another room and out the window, through a mirror (?) or another room in the back center. We imagine that the major source of light is a an unseen window to the right. Whites and golds predominate the scene, with touches of blue and orange. Degas’s dancers, though quite strong, may seem delicate next to Caillebotte’s muscular workers.

In truth, Degas’ dancing girls and Caillebotte’s hard-working men are much the same. Their work is a labor of love, as the Impressionists saw it. The same can be said about Caillebotte, Degas, Durand-Ruel and those who left us with a wonderful record of life in Paris in the 1870s. The ballet painting was done in an opera house that destroyed by fire the very next year, probably caused by gaslights.

Recent Comments