The Gift of Van Gogh and the Power of Expressionism

Much of our appreciation of Van Gogh can be traced to Helene Müller, whose acquisitions are the foundation of the Kröller-Müller Museum. This German-born heiress was wise in recognizing Van Gogh’s genius and became the first major collector of his work. She and her Dutch husband, Anton Kröller, built a sensational collection and began showing parts of it to the public as early as 1913. They lost their fortune in the economic downturn after World War I, but formed the Kröller-Müller Foundation to protect the art. In 1935, they donated a house, land and a collection of 12,000 pieces to the Netherlands on the condition the country will build a place to display it. There were 90 paintings, 185 drawings by Van Gogh.

In a recent trip to the Netherlands, I was lucky to visit the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo with its awesome collection of Van Goghs. A month earlier I had seen a wonderful exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Van Gogh: Close Up, mostly paintings of nature. The 4 withered sunflowers, above, in the Otterlo museum, reminded me of the painting of two sunflowers I had seen in Philadelphia (from New York’s Metropolitan Museum).

However, we didn’t get to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where the lines were out of the door. Is there ever a time that to see a group of his paintings without big crowds? The public loves Van Gogh so much because everything pulsates and everything we feel and experience is felt so much stronger in his artworks.

My favorite Van Gogh in the Kröller- Müller Museum was The Café Terrace at Night, 1888, an outdoor view of the nightclub Van Gogh frequented in Arles. Intense contrast of yellow light meets the deep blue starry sky.

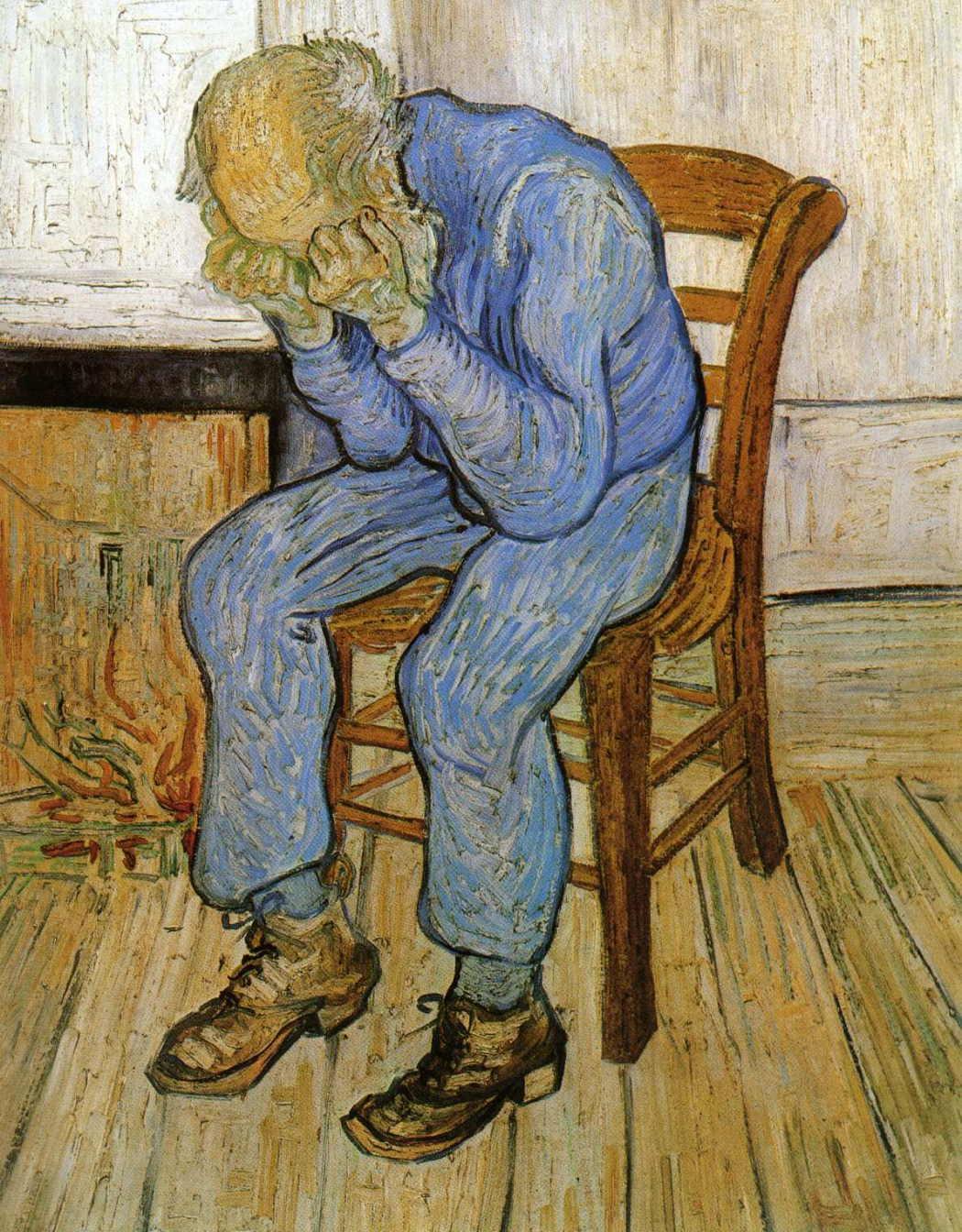

Color is sensual and color draws us into Van Gogh because his blues, greens and yellows are unique, out of this world in their beauty. Applied with heavy brush strokes, Van Gogh lines and shapes form a variety of 3-dimensional textures coming out into space, up into space or around the canvas. We witness the fury of his emotions. Students are fascinated with the details of his life, why he cut off part of an ear and later committed suicide in 1890. Van Gogh wrote of his depression and suicidal thoughts, while others described his manias. Some of his best production seems to have been painted in periods of mania. He suffered from epilepsy and drank too much absinthe. Extremes of mood made him hard to tolerate, but fostered his great genius.

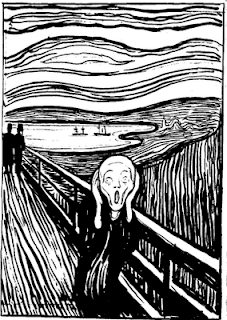

As a student, Cezanne and Gauguin were my early favorites of Post-Impressionism. I didn’t want to be overwhelmed by the intensity of Van Gogh ….or Edvard Munch. Munch’s painting of The Scream, 1893, anticipated what was to come in the 20th century– Depression, world wars, genocides. Van Gogh certainly was a huge influence on the art of Munch and other Expressionists.

As a student, Cezanne and Gauguin were my early favorites of Post-Impressionism. I didn’t want to be overwhelmed by the intensity of Van Gogh ….or Edvard Munch. Munch’s painting of The Scream, 1893, anticipated what was to come in the 20th century– Depression, world wars, genocides. Van Gogh certainly was a huge influence on the art of Munch and other Expressionists.

Vincent Van Gogh and Edvard Munch had the power to visualize and portray intensity of feelings that most of us humans feel at times, though we might not admit it, or we may not be able to express it. Van Gogh in the 1880s and Munch in the 1890s experienced a world that was rapidly changing and adjustment would not be easy. We can understand the difference between old and new life in the very first painting Helene Müller bought. Paul Gabriël’s Train in Landscape, a traditional painting of c.1887, describes the Dutch world at the time of Van Gogh, one leg in the past and one in the future.

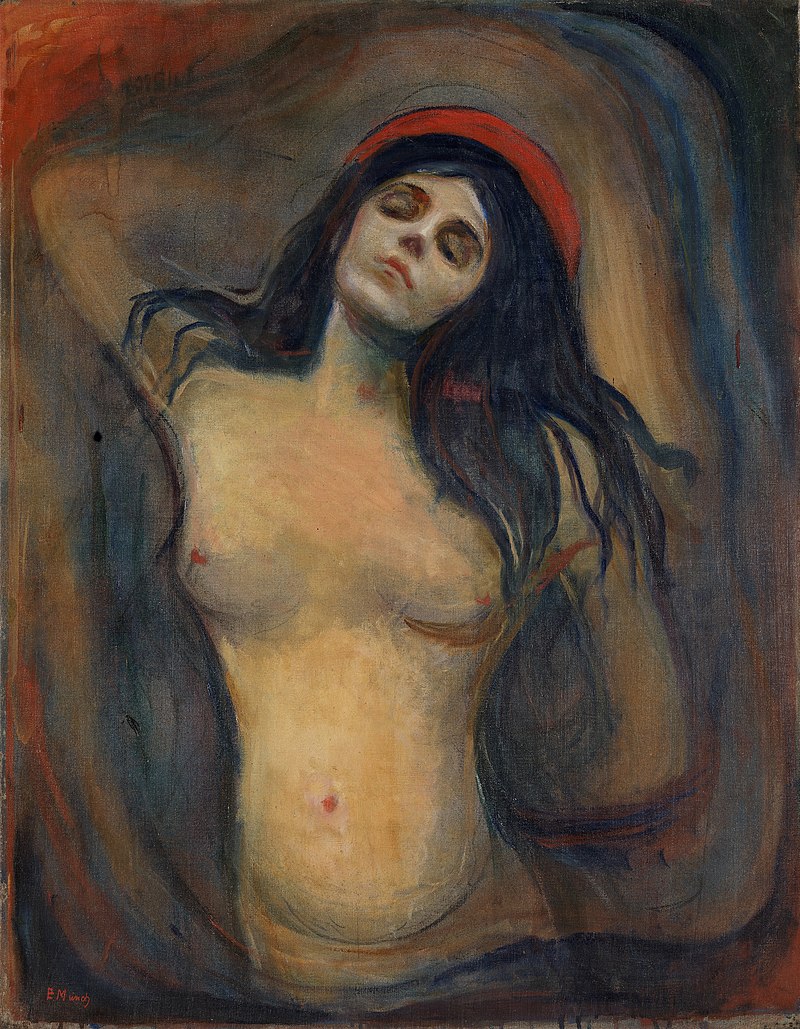

I thank Helene Müller for bringing Van Gogh’s art to the public. She also patronized modern artists of her time, such as Picasso, Fernand Leger, Diego Rivera, Dutchmen Piet Mondrian and Bart van der Leck. She collected many other 19th century modernists: Manet, Monet, Cezanne, Renoir, Pissarro, Gauguin and Munch. In 1922, Helene Muller bought her last painting, Le Chahut by Georges Seurat, a delightful circus image which gives us light-hearteded break from the serious emotions of Van Gogh.

Recent Comments