by Julie Schauer | Mar 24, 2014 | African-American Art, American Art, Christianity and the Church, Smithsonian American Art Museum

|

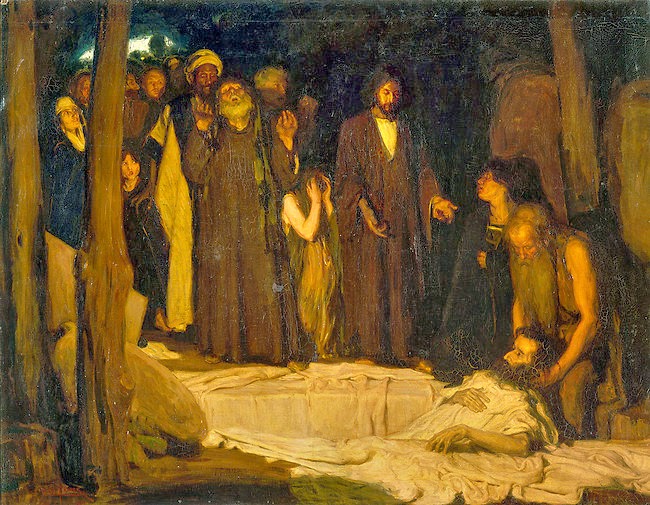

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Raising of Lazarus, Musee d’Orsay, Paris, 1896 |

Henry Ossawa Tanner, the most important African-American painter born in the 19th century, should probably be considered America’s greatest religious painter, too. He came into the world in when our country was on the brink of its Civil War, in Pittsburgh, 1859. Though his paintings are profound, he normally doesn’t get as much recognition as he deserves.

Religious painting has never been a significant genre in the United States. Mainly, it has been used for book illustration and in churches with stained glass windows. Of course, Europe had its own rich tradition of paintings for Catholic Churches and even in the Protestant Netherlands, Rembrandt made paintings and prints of biblical subjects for their religious significance.

Tanner reinvented religious painting with highly original interpretations. His father was a minister in the AME Church who ultimately became the bishop of Philadelphia in 1888. His mother was born in slavery, but escaped on the underground railway. Although Tanner was born free, he obviously experienced turbulent times and discrimination; faith could have given him solace.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Annunciation, 1894, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts |

In 1894, Tanner painted Mary, mother of Jesus, at the Annunciation, the biblical story of an angel announcing to Mary she is to be the mother of God. Typical Annunciation scenes put a flying angel interrupting a teenage girl in her bedroom. Tanner leaves out the angel and only a beam of light represents the divine encounter. Pictured as a young women in her bedroom, Mary reflects inward on the meaning of the light, knowing God has things in mind for her. The painting is absolutely beautiful, a show-stopper with a profound imagining of how Christ’s earthly life began. The streak of light appears as the leg of the cross as it passes through a horizontal shelf on the wall. When we notice this detail, we’re given a hint of how Jesus’ life ended, death by crucifixion.

|

| detail-The Raising of Lazarus |

Tanner’s technique uses mainly the pictorial language of realism to convey divine presence on Earth, in contrast to Abbot Handerson Thayer who used symbolic angels and winged figures in an idealized classical figural style. Another way to explain the difference is to say that Tanner painted in a vernacular language, instead of using the classical Latin language. His religious stories are without supernatural excess, but he uses light strategically to illuminate miracles.

Although born in Pittsburgh, most of his early life was in Philadelphia. He became the pupil of legendary teacher Thomas Eakins in 1879. Although Eakins considered him a star pupil, he faced racial prejudice from other students. Not receiving recognition in the United States, he set out for Europe in 1891, and received additional training at the Academe Julian in Paris. Philadelphia may have been the best place for an American to study art in the 19th century, but Paris was the best place for an artist to be. By 1895, his work was accepted in the Paris Salon. The next year he received an honorable mention at the Salon, and in 1897, his recognition was complete with The Raising of Lazarus, 1896. The success which alluded him the US came after only a few years living in France.

The Raising of Lazarus (top of this blog page, and to the right.) received a third class medal in the Paris Salon, but it also became the first painting to be bought by the nation of France and placed in a national museum. The painting tells the story of Jesus going into the grave of Lazarus to bring him back to life, with sisters Mary and Martha and a group of his stunned followers. Tanner captures in paint the earthly event as it actually could have taken place, but uses heightened light-dark contrast to illuminate the miracle.

|

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Two Disciples at the Tomb, 1906

Art Institute of Chicago, 51 x 41-7/8″ |

|

We can think of Tanner as similar to Caravaggio who introduced dramatic light – dark contrast to show that the calling to follow the Lord is a mysterious event. More importantly, we can think of Tanner like Rembrandt, who used light to convey subtle and mysterious psychological states that accompany a person undergoing a spiritual awakening, or witnessing a miracle. As in the works of both the earlier artists, the drama becomes an interior event.

In 1906, Tanner’s painting of Two Disciples at the Tomb won first prize at the Art Institute of Chicago’s 19th exhibition of American painting.. In it, Peter, the older man points to himself as if saying “Oh my God,” while the younger apostle John raises is head straining to with expectancy to see fulfillment of Jesus’ promise with the Resurrection. Light is strategically placed on the whitened necks against dark clothing, and the glow of their bony faces radiate a sudden awareness of the miraculous event of Christ’s Resurrection. They’re the faces of simple men, whose faith has saved them.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Three Marys, 1910 Fisk University, Nashville, TN 42″ x. 50″ |

The Three Marys is a particularly beautiful portrait of women as they see the light in front of Jesus’ tomb and that he has risen from the dead. The witnessing of a miracle is a profound spiritual event. Each woman has a slightly different psychological response. Like many of Rembrandt’s paintings, The Three Marys is nearly monochromatic, with blue as the primary color. He explained the intent of his paintings, “My effort has been to not only put the Biblical incident in the original setting, but at the same time give it the human touch….to try to convey to the public the reverence and elevation these subjects impart to me.” It seemed that as time went on, the blues get stronger and stronger in his paintings.

|

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson, 1893

Hampton University, Hampton, VA |

|

|

Actually Tanner’s best know paintings are The Banjo Lesson, 1893, at Hampden University and The Thankful Poor, 1894, in a private collection. He painted them on return to the United States and based them on memories from travel in North Carolina. Instead biblical stories, these paintings are scenes of everyday life. Yet they have a religious significance in their contemplative spirit and the suggestion of humility. The Banjo Lesson has two sources of light, an unseen window and an unseen fireplace or stove to the right. The glow of light shows that he was familiar with Impressionism and applied some of its diffusive, scattered light it.

Tanner traveled extensive to the Middle East and into the Islamic world. Trips to Egypt and Palestine in 1897 and 1898 may have given him inspiration for the settings in his paintings. After 1900, he developed a looser style, with more tonalism and the possibility of becoming more poetic.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, Abraham’s Oak, 1905, Smithsonian American Art Museum |

As we may expect, the city of Philadelphia has a substantial collection of his work, particularly where he studied, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The Smithsonian American Art Museum has a large collection of his works also. I particularly like Abraham’s Oak, which can be read as a pure landscape painting. Also fairly monochromatic, the painting reflects the Tonalist style prevalent in the United States at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. Tonalist landscapes are moody, evocative, contemplative and spiritual. He combines the underlying beauty in nature with a symbolic oak, the place Abraham staked out for his people as the Jewish patriarch.

Like the great early 19th century artist Eugene Delacroix, Tanner was fascinated by North African subjects and themes. (I see Delacroix’s influence in the vivid colors and the way he treated the floor patterns in The Annunciation.) He went to Algeria in 1908 and Morocco in 1912. The Atlas Mountains of Morocco are said have been inspiration a late painting, The Good Shepherd, also in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Figures became smaller, but faith is still his driving force. The unification of subject with landscape has increased. There’s a huge precipice these sheep could fall down, but their loving shepherd protects them. According to Jesse Tanner, his son, the artist believed that “God needs us to help fight with him against evil and we need God to guide us.” He lived to be 79, dying in 1937.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Good Shepherd, c. 1930 Smithsonian American Art Museum |

(I have seen only one exhibition of his paintings at the Terra Museum of American Art, back around 1996 and the work mesmerized me.) An exhibition in Philadelphia two years ago attempted to bring Tanner the recognition due to him. Here’s a professor’s review of the exhibit which also traveled to Cincinnati and to Houston.

There may be reasons apart from racism as to why he is not more famous in America. The United States lacks a tradition of religious painting and doesn’t easily embrace it. Furthermore, art historians celebrate artists who are innovators, those who bring art forward. Although Tanner was painting at the time of Picasso, Matisse, Kandinsky, Klee and O’Keeffe, he was not strongly affected by their trends of change. He stayed true to himself and in that way, he is a prophet of his faith rather than a prophet of the avant-garde.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Mar 23, 2014 | 19th Century Art, American Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Art Institute of Chicago

|

| Abbot Handerson Thayer, Winged Figure, 1889, The Art Institute of Chicago |

It may be the dreamer in me who is so attracted to the winged paintings of Abbott Handerson Thayer. The first of his paintings that I fell in love with was Winged Figure. above, at the Art Institute of Chicago. I’ve always admired the loose simplicity of the Grecian style of clothes, even before studying Greek art. However, what appeals most to me is the sense of security and peace this figure has as she sleeps, protected and held by the curve of her wing. Her leg and golden garment are strong and sculptural, but it’s not clear if she’s on the ground or on a cloud.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Angel, 1887, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of John Gellatly Mary, the artist’s daughter, posed. |

After moving to Washington, I found that Thayer is represented well in the nation’s capital. Angel of 1887 is a very young figure, and Thayer’s daughter Mary served as the model when she was 11. She’s frontal, symmetric, quite pale and white. She may or may not be in flight. Thayer is probably the premier American painter of angels, a Fra Angelico or a Luca della Robbia in paint. He gives them an idealized beauty and paints in a pristine Neoclassical style, as well as Europeans did.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, A Winged Figure, 1904-1913, The Freer Gallery of Art,

Smithsonian Institution Gift of Charles Lang Freer. The model is the

artist’s daughter, Gladys |

One of the winged figures at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art wears a laurel wreath. More rigid than his other angels, she faces us frontally with the geometry of a Greek column. Her face is severe, too, and she doesn’t quite touch the ground. Daughter Gladys was his model. (The Freer Gallery of the Smithsonian has published an explanation of the Winged Figures collected by Charles Lang Freer.)

Thayer’s preference for painting winged figures was not entirely religious. His interest in naturalism started as a 6-year old living near Keene, New Hampshire, when he began the avid study of birds and nature. However, his obsession with painting winged figures, angels and innocent children may have something to do with the fact that two of his children died unexpectedly in the early 1880s. That so many of his figures gained wings may represent hopes he had for coming to terms with loss.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Virgin, 1892-93,

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution Gift of Charles Lang Freer

(The artist’s children, Gladys, Mary, Gerald) |

|

|

|

|

He painted his three remaining children over and over again, and three of these paintings are in the

Smithsonian American Art Museum. In

Virgin at the Freer Gallery of Art, the oldest Mary faces us frontally walking in a pose similar to the

Nike of Samothrace. Although she doesn’t technically have wings like the Nike of Samothrace, the clouds behind her become large, white wings. Mary is an icon in the center who boldly holds and leads the younger sister and brother. She is noble and unflappable but moves swiftly. The younger children are strong, too, and do not smile. Their hair flies in the wind and the ground they walk on is hazy. Above all, they’re innocent. (These two younger children, Gladys and Gerald, also became painters.)

Understandingly, there was some intense melancholy surrounding he and his wife for some time. In 1891, his wife died, too. Thayer may be sentimental, but the paintings of his children would suggest he wanted them to be strong, triumphant and prepared for any event.

|

| Abbott Handerson Thayer, Roses, 1890, oil on canvas 22 1/4 x 31 3/8 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly |

Thayer was a superb painter of other subjects. He also did portraits, landscapes and still lives, which can be found on the Smithsonian’s website. An exceptional still life at Smithsonian American Art Museum, Roses, demonstrates his incredible skill. He manages to be highly detailed with the leaves and blooms but spontaneous and expressive for the vase and background. The color is somewhat muted, but the texture is strong. The style of his still lives compares well to Edouard Manet’s textured still lives and the pristine beauty Henri Fantin-Latour’s still lives. Like the highly skilled academic painter Bouguereau, he seems to be able to combine the best of the great 19th century styles: Neoclassicism, Realism and the emotional or dreamy qualities of Romanticism.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Mount Monadnock, 1911, 22 3/16 x. 24 3/16 “

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC |

The other great style of the period was Impressionism, which captured the fleeting qualities of light and colors. While Thayer may not be categorized as an Impressionist, he should be added to the list of marvelous snow painters. His best scenes of snow come from the area near where he lived in Keene and in Dublin, New Hampshire. In the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s Mount Monadnock, 1911, Thayer captured some of the beautiful scenery surrounding this mountain very familiar to him. There are vivid blues, purples and reds in this snow and the lights on the mountain top are brilliant. There’s a small, horizontal string of light coming across the ground to separate trees from mountain.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Monadnock No. 2, 1912,

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution. Gift of Charles Lang Freer |

He repeated the composition over and over, as Impressionists did. Mount Monadnock, 1904 and Monadnock No. 2, 1912 are in the Freer Gallery of Art. The snow topped mountain is also brilliant and even whiter in the painting of 1912. Touches purplish-gray suggest how cold it must have been. The trees are dark however, a definite force of nature. Thayer knew Impressionistic techniques and had lived in France, but he was also an artist who wanted to find some solidity and permanence in the world, even as it will change and be gone. He painted Winter Dawn on Monadnock in 1918, now in the Freer, too. There were less pine trees at this time, but the radiant pinks of dawn pervade the scene on the left.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Winter Dawn on Monadnock, 1918, The Freer Gallery of Art,

Smithsonian Institution Gift of Charles Lang Freer. |

Who can see and understand illusion in nature better than an artist? In 1909, he and his son, Gerald Handerson Thayer, wrote a major book on protective coloration in nature, Concealing and Coloration in the Animal Kingdom: An Exposition of the Laws of Disguise. He ascertained that in shadow birds or animals become darker to be hidden, but naturally turn lighter in sun. Another naturalist, former President Teddy Roosevelt, scoffed at his ideas and they were not accepted. However, he tried to share his ideas with the American government during World War I.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Stevenson Memorial, 1903, 81-7/16 x 16 1/8 “

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC Gift of John Gellatly |

Thayer made as a memorial, above, to author Robert Louis Stevenson, someone he deeply admired but did not know. His first idea was for the memorial was to paint his three children, in honor of Stevenson’s book,

A Child’s Garden of Verses. He changed his mind, and a winged figure sits on a stone marked VAEA, the spot in Samoa where Stevenson is buried.

Thayer memorialized Stevenson, but what about his salvation? In 2008, the Smithsonian did a documentary film about him, Invisible: Abbott Thayer and the Art of Camouflage. Apparently his ideas about camouflage are more readily accepted now than they were in his time. Doesn’t his reputation as a painter deserve wide recognition, too? While keeping a foothold here on earth, his winged figures suggest that humans have the potential to transcend the hard life and fly above our limitations.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by admin | Feb 22, 2013 | 19th Century Art, American Art, Hudson River School, Landscape Painting, Nature, The Civil War

|

| Frederic Edwin Church, Meteor of 1860, is in the collection of Judith Filenbaum Hernstadt |

Photos of the asteroid and a meteor which hit in Russia this past week reminded me of Frederick Edwin Church’s painting of a meteor, now on view in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s exhibition, The Civil War and American Art. This month we celebrate President’s Day, Black History Month, and Spielberg’s film of Lincoln in the Oscars, while the exhibition presents the historical and sociological aspects of the civil war as interpreted by artists of that time. Many paintings and photographs on display tell those stories, but there’s also a sub-theme of landscape as metaphor. The scenery of two Hudson River School artists, Church and Sanford Robinson Gifford, present geological and astronomical wonders with deeper meanings.

Church’s Meteor of 1860 connects to Walt Whitman’s poem in Leaves of Grass, Year of the Meteors (1859-60). While Whitman’s poem spoke of John Brown’s rebellion and the election of Abraham Lincoln, it also described “the comet that came unannounced out of the north flaring in heaven,” and “the strange huge meteor-procession dazzling and clear shooting over our heads. (A moment, a moment long it sail’d its balls of unearthly light over our heads, Then departed, dropt in the night, and was gone;)

Church painted two large meteors followed by a trail of smaller sparks whose trail runs parallel to the earth. Like Whitman’s description, his vision also appeared at night; it lit up sky in pink and cast a glowing reflection on the water. He wrote about the event he had seen from his home in the Hudson River Valley, Catskill, New York on July 20, 1860. Could he have seen this rare event as an omen?

|

| Frederic Edwin Church, Natural Bridge, Virginia, 1852 collection of the Fralin Art Museum, University of Virginia |

The earliest painting by Church in the Smithsonian exhibition is The Natural Bridge, Virginia, a geological formation in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, which George Washington had surveyed and Thomas Jefferson had owned at one time. His painting pulls our eyes upward to the meticulously painted detail of the rock against white clouds and a brilliant blue sky. Another story is told towards the bottom of the painting, where a black man explains this geographic wonder to a seated white woman, putting him in the authoritative position.

|

| Frederic Edwin Church, Icebergs, 1861, from the Dallas Museum of Art |

In 1859, Church had traveled by boat from New York to Labrador in search of icebergs. He exhibited one result, Icebergs, in New York on April 24, 1861, two weeks after war had broken out at Fort Sumter. Church responded to the national strife, renaming the painting The North—Church’s Picture of Icebergs, thus signaling his political stance. Church allocated all exhibition fees to a fund established to support the Union Soldiers’ Fund. The large, impregnable iceberg is said to represent the North itself. Church also may have wished to commemorate the Battle of Fort Sumter and signal his sympathies in another well-known painting owned by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Our Banner in the Sky.

|

| Frederic Edwin Church, Cotopaxi, 1862, oil on canvas, Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, Robert H. Tannahill Foundation Fund, Gibbs-Williams Fund, Dexter M. Ferry Jr. Fund, Merrill Fund, Beatrice W. Rogers Fund, and Richard A. Manoogian Fund. The Bridgeman Art Library |

Church traveled worldwide in his exploration of nature, natural wonders and exotic landscapes. In 1862, he painted the Cotopaxi volcano in Ecuador. Volcanoes are frequently seen as harbingers of war and upheaval. Frederick Douglas had said in 1861, “Slavery is felt to be a moral volcano, a burning lake, a hell on earth.” Cotopaxi, along with Icebergs, is one of the four large paintings which may be seen as allegories of the causes and events of the Civil War.

|

| Church, Aurora Borealis, 1865, in the Smithsonian American Art Museum |

Church painted the northern lights in 1865 based on sketches provided by explorer Israel Hayes’ sketches from a voyage to Labrador. Aurora Borealis is an expansive view of nature in blue, green yellow, orange and red. The halo of lights makes the sky look grand, while a boat shrinks next to its magnificence. Generally the northern lights were interpreted as omens of disaster, but fortunately the war ended during the year in which it was painted.

|

| Frederic Edwin Church, Niagara Falls, 1857, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC |

There are other important paintings by Church in Washington, DC, including the National Gallery’s El Rio de Luz. The Corcoran Gallery of Art owns Niagara Falls, 1857, above. During the 19th century, lithographs of this painting circulated the country at a time when travel was not easy and photography was not widespread. It’s worth going to the Corcoran to see the painting. A gorgeous rainbow rises through the mist and spray, but is only visible by surprise when one stands in front of the real painting, not computer reproduction. Frederic Church can be thanked for painting and interpreting the art of nature and for reminding us of mother nature’s greatness.

by Julie Schauer | Dec 5, 2010 | 19th Century Art, American Art, Exhibition Reviews, Landscape Painting

Thomas Cole, Sunset on the Arno, 1837, is at the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley until January 23. The exhibition, organized by the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, is from a private collection. Whispy clouds hover above, almost like angels.

Forty paintings from the Hudson River School of painting glow in the Shenandoah Valley, in the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley, Winchester, VA. Certainly this location has some resemblance to the Hudson River Valley and these paintings would naturally resonate in the community. Just as the 19th century artists centered mainly in New York and New England hoped to capture and hold onto the natural beauty of their unspoiled nature, the Shenandoah Valley still offers a resting place from too much human development. Entitled “Different Views of Hudson River Painting,” the paintings will be in Winchester until January 23.

Jasper Francis Cropsey, The Narrows of Lake George, in the Hudson River Museum. A smaller, view of Lake

Jasper Francis Cropsey, The Narrows of Lake George, in the Hudson River Museum. A smaller, view of Lake George with similar colors is on view is in the in the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley

In this two-room exhibition, many pristine paintings are arranged amongst poetry and quotations by Walt Whitman, William Cullen Bryant and others. The four seasons and many sunsets are on view. These paintings capture views we occasionally see in the mountains or countryside in those moments of nature’s most beautiful light and color. I was particularly drawn to Jasper Francis Cropsey’s radiant, reflecting color in Lake George, reminding me of the beautiful autumn that has just passed. Much if its appeal is that this painting and several others allow us to remember something and then hold onto it.

John William Casilear, Quiet River (Genesee), 1874. Often there are usually more cattle than people in the Hudson River paintings.

John William Casilear, Quiet River (Genesee), 1874. Often there are usually more cattle than people in the Hudson River paintings.

The majority of paintings are small and intimate; brushstrokes are minute and very detailed. People and animals, if depicted, are extremely small to show the grandeur of the natural world. The air is clean, often hazy, and the water is totally placid. We are invited into contemplation.

There are majestic views of Niagara Falls and Mount Washington, but also simple scenes of unknown places such as John William Casilear’s Quiet River (Genesee),1874. There is nothing intellectual about the exhibition, only the opportunity for reverie in peaceful, pastoral places. Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson School and painter of the Journey of Life series in Washington’s National Gallery, often painted his landscapes as allegories, but there doesn’t seem to be an underlying message in this Italian scene, Sunset on the Arno–unless the clouds are seen as angels.

such as John William Casilear’s Quiet River (Genesee),1874. There is nothing intellectual about the exhibition, only the opportunity for reverie in peaceful, pastoral places. Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson School and painter of the Journey of Life series in Washington’s National Gallery, often painted his landscapes as allegories, but there doesn’t seem to be an underlying message in this Italian scene, Sunset on the Arno–unless the clouds are seen as angels.

Laura Woodward, Adirondeck Woodland with Deer, has an infinite variety of greens, from very light to dark. The two deer are barely shown against the daylight around the bend of a stream and under the tall trees on the right.

The entire exhibition helps us understand why the Hudson River School is still admired. Alexis Rockman, a contemporary New York painter featured in this blog’s next entry was influenced by the Hudson River School.This distinctive American style of painting was importan t from the 1830s to 1880s. Impressionism in France had a much bigger influence on modernism and is usually more popular, but these artists–and there are so many of them– deserve a long look and a lot of our respect.

t from the 1830s to 1880s. Impressionism in France had a much bigger influence on modernism and is usually more popular, but these artists–and there are so many of them– deserve a long look and a lot of our respect.

At home I have a small painting on a plate, done in the Hudson River style by my great-grandmother. A gift to my great-grandfather, it is signed on the reverse, “From Helen to James, painted between Xmas and New Year’s 1889.

George Inness, Moonlight, Tarpons Springs, 1892, is in the Phillips Collection and part of the current exhibition, Side by Side, which offers comparison to paintings in Oberlin College’s Allen Art Museum. Along with Ralph Blakelock’s Moonlight and three other moonlight paintings, it can be seen until January 16Washington museums also have several paintings of the Tonalists who came after the Hudson River School and were generally more painterly. These artists used more layers and show greater influence from the techniques of French painters, particularly from the Barbizon School. The Tonalist painters of moonlight scenes, offer a nice comparison with the sunsets of Hudson River painters—less color but perhaps even more evocative of moods. These paintings include several by Ralph Albert Blakelock at the National Gallery, Phillips, Corcoran and Smithsonian American Art Museum, as well as paintings by George Inness.

Here is a blog devoted to the Hudson River School: http://circa1855.blogspot.com/

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by admin | Dec 5, 2010 | 19th Century Art, American Art, Hudson River School, Landscape Painting, Nature

Thomas Cole, Sunset on the Arno, 1837, is at the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley until January 23. The exhibition, organized by the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, is from a private collection. Whispy clouds hover above, almost like angels.

Forty paintings from the Hudson River School of painting glow in the Shenandoah Valley, in the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley, Winchester, VA. Certainly this location has some resemblance to the Hudson River Valley and these paintings would naturally resonate in the community. Just as the 19th century artists centered mainly in New York and New England hoped to capture and hold onto the natural beauty of their unspoiled nature, the Shenandoah Valley still offers a resting place from too much human development. Entitled “Different Views of Hudson River Painting,” the paintings will be in Winchester until January 23.

Jasper Francis Cropsey, The Narrows of Lake George, in the Hudson River Museum. A smaller, view of Lake

Jasper Francis Cropsey, The Narrows of Lake George, in the Hudson River Museum. A smaller, view of Lake George with similar colors is on view is in the in the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley

In this two-room exhibition, many pristine paintings are arranged amongst poetry and quotations by Walt Whitman, William Cullen Bryant and others. The four seasons, many sunsets and other wonders of nature are on view. These paintings capture views we occasionally see in the mountains or countryside in those moments of nature’s most beautiful light and color. I was particularly drawn to Jasper Francis Cropsey’s radiant, reflecting color in Lake George, reminding me of the beautiful autumn that has just passed. Much if its appeal is that this painting and several others allow us to remember something and then hold onto it.

John William Casilear, Quiet River (Genesee), 1874. Often there are usually more cattle than people in the Hudson River paintings.

John William Casilear, Quiet River (Genesee), 1874. Often there are usually more cattle than people in the Hudson River paintings.

The majority of paintings are small and intimate; brushstrokes are minute and very detailed. People and animals, if depicted, are extremely small to show the grandeur of the natural world. The air is clean, often hazy, and the water is totally placid. We are invited into contemplation.

There are majestic views of Niagara Falls and Mount Washington, but also simple scenes of unknown places such as John William Casilear’s Quiet River (Genesee),1874. There is nothing intellectual about the exhibition, only the opportunity for reverie in peaceful, pastoral places. Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson School and painter of the Journey of Life series in Washington’s National Gallery, often painted his landscapes as allegories, but there doesn’t seem to be an underlying message in this Italian scene, Sunset on the Arno–unless the clouds are seen as angels.

such as John William Casilear’s Quiet River (Genesee),1874. There is nothing intellectual about the exhibition, only the opportunity for reverie in peaceful, pastoral places. Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson School and painter of the Journey of Life series in Washington’s National Gallery, often painted his landscapes as allegories, but there doesn’t seem to be an underlying message in this Italian scene, Sunset on the Arno–unless the clouds are seen as angels.

Laura Woodward, Adirondeck Woodland with Deer, has an infinite variety of greens, from very light to dark. The two deer are barely shown against the daylight around the bend of a stream and under the tall trees on the right.

The entire exhibition helps us understand why the Hudson River School is still admired. Alexis Rockman, a contemporary New York painter featured in this blog’s next entry was influenced by the Hudson River School.This distinctive American style of painting was importan t from the 1830s to 1880s. Impressionism in France had a much bigger influence on modernism and is usually more popular, but these artists–and there are so many of them– deserve a long look and a lot of our respect.

t from the 1830s to 1880s. Impressionism in France had a much bigger influence on modernism and is usually more popular, but these artists–and there are so many of them– deserve a long look and a lot of our respect.

At home I have a small painting on a plate, done in the Hudson River style by my great-grandmother, as gift to my great-grandfather It is signed on the reverse, “From Helen to James, painted between Xmas and New Year’s 1889.

Washington museums also have several paintings of the Tonalists who came after the Hudson River School and were generally more painterly. These artists used more layers and show greater influence from the techniques of French painters, particularly from the Barbizon School. The Tonalist painters of moonlight scenes, offer a nice comparison with the sunsets of Hudson River painters—less color but perhaps even more evocative of moods. These paintings include several by Ralph Albert Blakelock at the National Gallery, Phillips, Corcoran and Smithsonian American Art Museum, as well as paintings by George Inness.

Here is a blog devoted to the Hudson River School: http://circa1855.blogspot.com/

by Julie Schauer | Mar 21, 2010 | American Art, Exhibition Reviews, Georgia O'Keeffe, Modern Art, The Phillips Collection, Women Artists

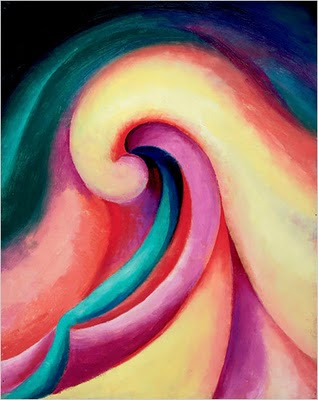

Series 1, No. 3, 1918, is from the Milwaukee Art Museum

Series 1, No. 3, 1918, is from the Milwaukee Art Museum

Once again the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, has put on a splendid exhibition of an early modern master, Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction. Although I’ve seen O’Keeffe exhibitions in the past, there is always something new to be seen in her work. Several compelling images that I had not seen before, especially from the Whitney Museum, a co-organizer of the exhibition, and the Milwaukee Art Museum, are in this show.

O’Keeffe’s abstract imagery is inspired by diverse subjects, more often natural than manmade–flowers, bones, mountains, aerial views, and the diverse places she lived, Wisconsin, Lake George, NY and New Mexico. Less well known is the fact that she lived in Charlottesville, Va., and some of her colors could easily be reflections of sunsets over the Blue Ridge Mountains. Even though a group of abstractions is inspired by music, one of the curators pointed out that Music, Pink and Blue, No. 2, resembles Natural Bridge, Va. The meaning of each single work is unique to the viewer; everyone who goes to visit the show is inclined to see something different and take their own inspiration from it.

The exhibition is enhanced by O’Keeffe’s charcoal drawings and the weather photographs of Alfred Stieglitz. One thing I recognized anew is the quality of O’Keeffe’s brushstrokes and how they reflect the particular form of each abstraction takes. Although photographs may provide a glimpse at her subtle blending of colors, it is only through seeing the exhibition that one can truly enjoy the wonder of O’Keeffe’s vision. It will be at the Phillips until May 9th, and then moves to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe.

Music, Pink and Blue, No. 2, from the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

t from the 1830s to 1880s. Impressionism in France had a much bigger influence on modernism and is usually more popular, but these artists–and there are so many of them– deserve a long look and a lot of our respect.

t from the 1830s to 1880s. Impressionism in France had a much bigger influence on modernism and is usually more popular, but these artists–and there are so many of them– deserve a long look and a lot of our respect.

t from the 1830s to 1880s. Impressionism in France had a much bigger influence on modernism and is usually more popular, but these artists–and there are so many of them– deserve a long look and a lot of our respect.

t from the 1830s to 1880s. Impressionism in France had a much bigger influence on modernism and is usually more popular, but these artists–and there are so many of them– deserve a long look and a lot of our respect.

Recent Comments