by Julie Schauer | Feb 15, 2015 | birds, Chris Allen, Fred Tomaselli, Greater Reston Arts Center, Ingrid Bernhardt, Laurel Roth Hope, Petah Coyne, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Tom Uttech, Walton Ford

|

Fred Tomaselli, Woodpecker, 2009, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

gouache, acrylic, photo collage and epoxy resin on wood, 72″ x 72″ |

I love talking about birds in my Art Appreciation classes, though with a focus very different from from the current SAAM (Smithsonian American Art Museum) exhibition, “The Singing and the Silence: Birds in Contemporary Art.” The exhibition’s message is about man’s relationship to birds, with the accent on environmental issues. My class talks about birds in flight, to symbolize our human aspirations. Flying birds remind us that humans can soar even if we don’t literally know how to fly.

|

Chris Allen, A Grand View, 2010, Stone, beads, fetish

Photo from Pinterest, Bonin Smith |

This exhibition and another excellent exhibition called “Bead,” at GRACE (Greater Reston Arts Center), honor the minutia of creation in thousands or millions of the small details that make up the birds. Both exhibitions are breathtakingly beautiful, must-see experiences, though their purposes are not at all similar. There’s only one week left to see the SAAM show, and almost two left weeks until “Bead” ends on February 28. Two of the 15 artists in “Bead” included birds, but the show also features well-known national artists such as David Chatt and Joyce J. Scott. There are many other masterful and surprising interpretations of beads. A pair of birds sitting on top of Chris Allen’s beaded stones is called A Grand View. Beads are skin for the timeless stones of the earth and Allen’s construction is a metaphor for relationship of body and soul. (Chris Allen reminds me of both a blog I wrote before and the great sculptor I admire, Brancusi.)

Back at SAAM, Fred Tomaselli’s Woodpecker, is a large painting, but its smallest details are mesmerizing. Three of his other large paintings are also in the exhibition, all densely patterned. Tomaselli, originally from Santa Monica, California, recalls growing up with bright colors of Disneyland, but also is quite a naturalist, a bird watcher and a lover of fly fishing. Today an exhibition of his work opens at the Orange County Museum of Art.

|

| Ingrid Bernhardt, Chic Chick, 2014, 5″ x 6″ 4″ papier-mâché, beads and feathers |

As in Woodpecker with its beautiful details, there’s a dedication to perfection in Ingrid Bernhardt’s Chic Chick at GRACE. It’s a papier-mâché bird with added beads and feathers. Tons and tons of the tiniest beads make it very intricate. From the fallen feathers, the artist has made some beautiful earrings which lie beside the bird. It’s quite a novelty and something special to behold. Bernhardt compares her beading technique to the pointillism of Seurat and all the dots of color he used.

|

Laurel Roth Hope, Regalia 63 x 40 x 22 in.

Private Collection

© Laurel Roth Hope. Image courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris

|

Chic Chick’s sheer beauty and attention to detail has lots of competition in the peacocks of California artist, Laurel Roth Hope, currently on view at SAAM. She makes peacocks out of hair clips, fake fingernails, fake eyelashes, jewelry, Swarovski crystal and other beauty symbols. One named Regalia, has all the pride associated with its species, and another sculpture named Beauty, is a composition of two peacocks who play the mating game. This bird traditionally is a symbol of Resurrection and eternal life in Christian art, and the artist evokes a power worthy of that traditional role. Her peacocks are amazingly realistic, but the technique and innovative use of material is an example of how an artist can show us how to see the world in a new way.

|

Laurel Roth Hope, Carolina Parokeet, crocheted yarn on

hand-carved wood pigeon mannequin, Smithsonian

American Art Museum |

Laurel Roth Hope is also concerned about the environment and biodiversity To celebrate certain species that are now extinct, she crocheted sweaters that mimic the coats and plumage of these lost birds. One, Carolina Parokeet, is in the SAAM’s permanent collection. Others in this group include the Passenger Pigeon, The Paradise Parrot and the Dodo. She used her hands to crochet sweaters in beautiful, tiny variegated colors and pattern. Much love goes into her creations. At the same time, we think of so many cultural concepts: beauty, pride, artifice (fake nails and fake eyelashes, loss, death. We ask ourselves: What does the outer coat (outer beauty)mean? What does pride mean if it bites the dust in the end? At the same time, the artist is giving tribute and memory to something that is lost.

|

| Laurel Hope Roth, Beauty, detail from the Peacock series photo from the website |

John James Audubon was America’s master artist of birds. Walton Ford is similarly a naturalist who works with combination techniques–watercolor, gouache, etching, drypoint, etc. He breaks with Audubon with his complex allegorical messages, however. environmental messages, however. Also among the 12 artists in the Smithsonian show, several are bird photographers.

|

Walton Ford, Eothen, 2001

watercolor, gouache, and pencil and ink on paper

40 x 60 in.

The Cartin Collection

Image courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery |

Only one of the artists, Tom Uttech, painted his birds in the way I usually imagine them — in flight. Uttech lives in Wisconsin, and his landscapes come from the North Woods, as well as a provincial park in Ontario. Some of his titles are impossible.

Enassamishhinijweian is my favorite. A bear’s back faces us, as he sits still and calmly observes the world of nature passing by. Multitudes of birds fly. An owl turns to look at us, and even a squirrel flies in the sky. The museum label mentions Uttech’s immersion in nature and his belief in its transformative power, much like Emerson and Thoreau. I’d guess that Uttech is also an admirer of

Heironymous Bosch, a 15th-16th century Dutch painter. He also loved panoramas.

A bear hidden in each of Uttech’s three large panoramic landscapes. These bears are probably the artist himself, or the individual who observes nature.

|

Tom Uttech, Enassamishhinjijweian, 2009, oil on linen, 103″ x112″ Collection of the Crystal Bridges Museum, Bentonville, Arkansas

© Tom Uttech. Image courtesy Alexandre Gallery, New York. Photo by Steven Watson |

Traditionally in art, birds in flight show contact between man and divinity. A bird symbolizes the Holy Spirit. In African and Oceanic cultures, the birds tie a living person to his ancestors. Only one of the artists I noticed at SAAM, Petah Coyne, sees her birds as the travel guides, the conduit between heaven and earth. Her elaborate black and purple sculpture is called Beatrice, after Dante’s beautiful guide through Purgatory, in The Divine Comedy. It’s about 12 feet high, and is dripping with birds and falling flowers. The beautiful work must be seen in person to be appreciated.

The many manifestations of birds reminds us of all the roles they fulfill: the silent and the singing and the flying. We end up with a new, profound appreciation for nature, and the hope to protect its beauty, birds included. These exhibitions helped me to see the vastness of this world, as well as the minutia of its details.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Dec 4, 2014 | 19th Century Art, Cassatt, Degas, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, National Gallery of Art Washington, Sculpture

|

| Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, 1878–1881,pigmented beeswax, clay, metal armature, rope, paintbrushes, human hair, silk and linen ribbon, cotton and silk tutu, linen slippers, on wooden baseoverall without base: 98.9 x 34.7 x 35.2 cm (38 15/16 x 13 11/16 x 13 7/8 in.) weight: 49 lb. (22.226 kg) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

|

It was a joy to see the Kennedy Center’s world-premiere production, The Little Dancer, which closed on November 30th. Tiler Peck, principle of the New York City Ballet had the lead as 14-year-old Marie van Goethem, the ballerina who posed for Degas’ famous statue, Little Dancer. Although Peck is definitely far more mature than Degas’ model was, she certainly was a good choice for the role. Boyd Gaines, as Degas, really does not look like him but I guess it doesn’t matter. Some of the settings and compositions are the same as you will see in his paintings. (My blog about Degas’s paintings of dancers)

|

The music is delightful, and most of the story is fairly credible, so I do hope the musical will go to more venues. The Kennedy Center audiences loved it. The musical fits in with what I’ve been writing about, Degas and Cassatt and the relationships between artists. The story opens in 1917 with a visit to Degas’ household after his death. Mary Cassatt is there, wishing to turn the ballerina away, but she came back to see the sculpture he did of her many years earlier. It’s fairly funny as it refers to the yellow coat with a fur collar that was annoying to Marie.

|

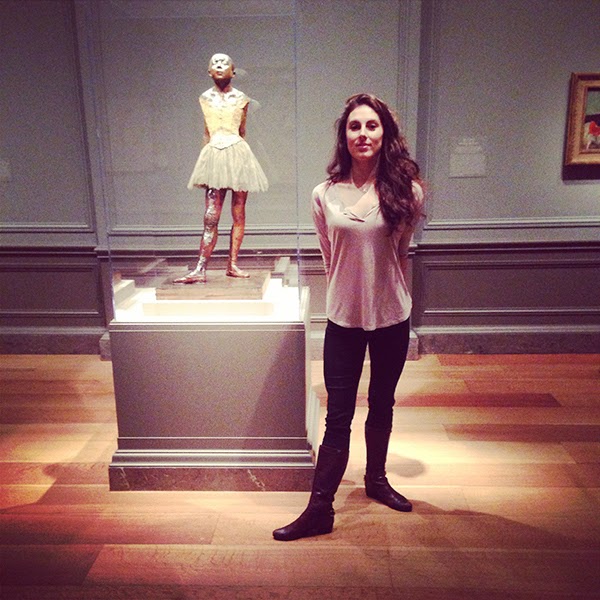

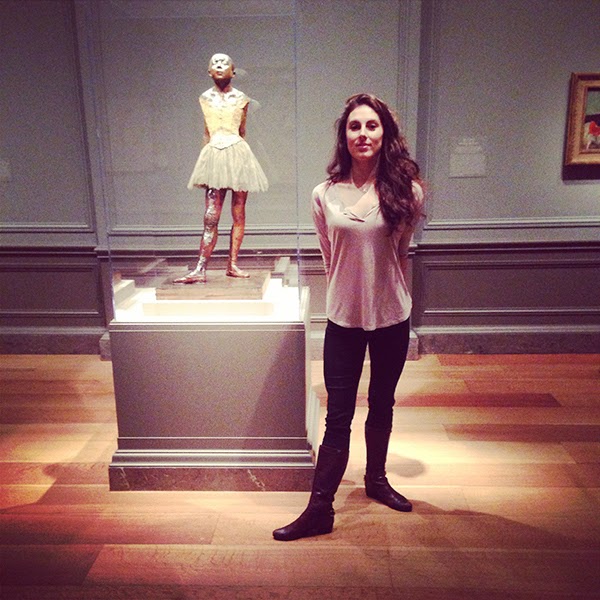

| Tiler Peck in front of the National Gallery of Art’s Little Dancer Aged Fourteen , from Tiler Talks Blog, October 15, 2014 |

The story is truthful in that portrayed some of the challenges in the lives of the dancers who were working class girls. Marie’s mother was a laundress, and I’m guessing she posed for Degas, too. Laundresses — like dancers and race horses — were part of Degas’ continuous subject matter, as he studied the movements of muscles and limbs at work and in stress. (While we think of dancers and race horses expressing consummate grace, we don’t think of laundresses that way.) In the play, Marie was put into a competition with snooty, upper class girl who had a stage mother, a story for a Disney movie or a story which would be more truthful today. Wealthy girls were not so likely to be ballerinas in the 19th century, as their parents wouldn’t have subjected them to gawking men. Class differences, as a major theme of the play, are historically correct for the time. Other details of biography, Degas’ grumpy outer shell that hid his softness, his sensitivity to strong light and fear of going blind were woven into the tale. Of course, the close companionship and artistic relationship with Mary Cassatt, especially during the time Marie would have posed, were very true.

|

| Tiler Peck as Marie, the Little Dancer, in the Kennedy Center Musical of that name |

The musical, too, has flashbacks to old the older and younger Marie. Rebecca Luker, an experienced Broadway star who plays the older Marie, has a powerful voice. The musical is similar to a recent genre of books which use a work of art to create a historical fiction. Like Girl with a Pearl Earring, Tracy Chevalier’s book about Jan Vermeer and his famous subject, much of the details are imagined.

For the importance of the statue artistically, the National Gallery of Art will have Little Dancer Aged Fourteen on display in an exhibition with other sketches, paintings and sculpture until January 11, 2015. I think the importance of Degas’ wax sculptures as comparable the importance of his sketches. Waxes to bronzes are like drawings are to paintings, although not necessarily the case here. It helped him realize his vision for his paintings.

|

Fourth Position Front, on the Left Leg, c. 1885/1890 pigmented beeswax, metal armature, cork, on wooden base

overall without base: 60.3 x 37.8 x 34.1 cm (23 3/4 x 14 7/8 x 13 7/16 in.)

height (of figure): 56.8 cm (22 3/8 in.)

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon |

Degas built the statue in wax over an armature, and he did it in an additive process. In the play, it is called a “characterizing portrait.” and As such, it was quite innovative. Details are not the important part as much as the essence the characterization. The play opens with a famous by Degas: “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.” What Degas did so brilliantly make us see the essence of the practice, the work, the attitude and the dedication which made the ballet become what it became. Most of his paintings are of rehearsals rather than performances. Seeing his work makes our lives richer, and seeing “Little Dancer” enriches us. Even the 6-year old boys near me were entranced by it.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Oct 1, 2014 | 19th Century Art, Cassatt, Degas, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Portraiture, Women Artists

|

| Mary Cassatt, La Loge, 1878-79 |

Mary Cassatt was several years younger than Edgar Degas, but when he saw her work he exclaimed, “Here’s someone who sees as I do.” Currently, the National Gallery is showing Cassatt side by side with Degas, comparing how they two worked together and shared. Both are remarkable portrait artists.

Like Manet and Morisot, their relationship was especially helpful for each of them reach the fullness of artistic vision. They spent about ten years working closing together. As their artistic visions changed, they grew in different directions. They share same daring sense of composition. Both are excellent portrait artists. I just finished reading Impressionist Quartet, by Jeffrey Meyers. It’s the story of Manet, Morisot, Degas and Cassatt: their biographies, their art and their interdependence.

|

| Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt |

Degas and Manet were good friends, too, and had a friendly competition. They had much in common, having been born in Paris and coming from well-to-do backgrounds. Both had a strong affinity for Realism, but Degas was the greater draftsman, and probably the greatest draftsman of the late 19th century. (Read my blog explaining Degas’s dancers) Cassatt and Morisot also were friends, as the two women who were fixtures of the Impressionist group. They were very close to their families, and their subjects were similar. Their personalities were quite different. Berthe Morisot was refined and full of self doubt, while Mary Cassatt was bold and confident. Cassatt did not have Morisot’s elegance or her beauty.

Her confidence shines in all of Degas’ portraits. She was not too pleased with the portrait at right, but Degas often did get into the character of his subjects. Degas painted her leaning forward and bending over, and holding some cards. He put her in a pose used in at least two other paintings, but I’m not certain what he meant by this position. The orange and brown earth tones, and the oblique, sloping asymmetric composition are very common in Degas’ paintings.

Degas may have been somewhat shy, but caustic, biting and moody. By all accounts, it appears that Cassatt made him a happier person. Degas was the one who invited her to join the Impressionist group in 1877, three years after it had formed.. They worked together to gain skills in printmaking. In addition, to their common artistic goals and objectives, both had fathers who were prominent bankers. Mary Cassatt was an American from Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, while Degas had relatives from his mother’s family who lived in New Orleans. Some of his father’s family had moved to Naples, Italy, and had married into the aristocracy there.

No on seems to know if they were lovers. Both artists were very independent, remained single their entire lives. Neither was the type who really wanted to be married. However, each of them had proposed to others when they were very young, and before they knew each other. Writers don’t spend a lot of time speculating about their love lives, still an unknown question. Most art historians believe Degas sublimated his sexual energies fairly well while exploring the young girls and teens who were ballet dancers.

|

| Degas, Henri De Gas and His Niece Lucie, 1876 |

I have always loved this painting of Henri De Gas and his niece Lucie, from the Art Institute of Chicago. It seems a very sympathetic portrait of his uncle and cousin, both of whom have kindly faces. Sometimes it’s been explained that the chair as a vertical line showing the separateness of the relationship. I see it differently. The composition has a large diagonal, and an arc brings are eye from the upper right side to the lower left corner. A continuous compositional line from their heads down to the edge of his hand and the newspaper pulls the older man and young girl together. There heads are nearly at the same angle, single expressing their togetherness. The uncle looks like such a kindly man, and both look at us the viewers.

|

| Marry Cassatt, Portrait of Alexander Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso Cassstt |

Mary Cassatt also shows an even stronger family bond in the Portrait of Alexander Cassatt and His Son, Robert Kelso Cassatt, her brother and nephew. Her brother ultimately rose to be President of the Pennsylvania Railroad and may have been somewhat of a robber baron. You would never see his harshness in his sister’s portrayal. He seems like the ultimate warm, affectionate father. The two faces are placed so closely together, and they’re similar. Degas and Cassatt often portrayed individuals in relation to each other to show their great affection for each other, so differently from the way Manet did. In most of his group portraits Manet makes us keenly aware that each individual is a unique soul. He emphasizes differences and oppositions,

One the best of Mary Cassatt’s portraits is the Young Girl in a blue armchair.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Mar 24, 2014 | African-American Art, American Art, Christianity and the Church, Smithsonian American Art Museum

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Raising of Lazarus, Musee d’Orsay, Paris, 1896 |

Henry Ossawa Tanner, the most important African-American painter born in the 19th century, should probably be considered America’s greatest religious painter, too. He came into the world in when our country was on the brink of its Civil War, in Pittsburgh, 1859. Though his paintings are profound, he normally doesn’t get as much recognition as he deserves.

Religious painting has never been a significant genre in the United States. Mainly, it has been used for book illustration and in churches with stained glass windows. Of course, Europe had its own rich tradition of paintings for Catholic Churches and even in the Protestant Netherlands, Rembrandt made paintings and prints of biblical subjects for their religious significance.

Tanner reinvented religious painting with highly original interpretations. His father was a minister in the AME Church who ultimately became the bishop of Philadelphia in 1888. His mother was born in slavery, but escaped on the underground railway. Although Tanner was born free, he obviously experienced turbulent times and discrimination; faith could have given him solace.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Annunciation, 1894, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts |

In 1894, Tanner painted Mary, mother of Jesus, at the Annunciation, the biblical story of an angel announcing to Mary she is to be the mother of God. Typical Annunciation scenes put a flying angel interrupting a teenage girl in her bedroom. Tanner leaves out the angel and only a beam of light represents the divine encounter. Pictured as a young women in her bedroom, Mary reflects inward on the meaning of the light, knowing God has things in mind for her. The painting is absolutely beautiful, a show-stopper with a profound imagining of how Christ’s earthly life began. The streak of light appears as the leg of the cross as it passes through a horizontal shelf on the wall. When we notice this detail, we’re given a hint of how Jesus’ life ended, death by crucifixion.

|

| detail-The Raising of Lazarus |

Tanner’s technique uses mainly the pictorial language of realism to convey divine presence on Earth, in contrast to Abbot Handerson Thayer who used symbolic angels and winged figures in an idealized classical figural style. Another way to explain the difference is to say that Tanner painted in a vernacular language, instead of using the classical Latin language. His religious stories are without supernatural excess, but he uses light strategically to illuminate miracles.

Although born in Pittsburgh, most of his early life was in Philadelphia. He became the pupil of legendary teacher Thomas Eakins in 1879. Although Eakins considered him a star pupil, he faced racial prejudice from other students. Not receiving recognition in the United States, he set out for Europe in 1891, and received additional training at the Academe Julian in Paris. Philadelphia may have been the best place for an American to study art in the 19th century, but Paris was the best place for an artist to be. By 1895, his work was accepted in the Paris Salon. The next year he received an honorable mention at the Salon, and in 1897, his recognition was complete with The Raising of Lazarus, 1896. The success which alluded him the US came after only a few years living in France.

The Raising of Lazarus (top of this blog page, and to the right.) received a third class medal in the Paris Salon, but it also became the first painting to be bought by the nation of France and placed in a national museum. The painting tells the story of Jesus going into the grave of Lazarus to bring him back to life, with sisters Mary and Martha and a group of his stunned followers. Tanner captures in paint the earthly event as it actually could have taken place, but uses heightened light-dark contrast to illuminate the miracle.

|

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Two Disciples at the Tomb, 1906

Art Institute of Chicago, 51 x 41-7/8″ |

|

We can think of Tanner as similar to Caravaggio who introduced dramatic light – dark contrast to show that the calling to follow the Lord is a mysterious event. More importantly, we can think of Tanner like Rembrandt, who used light to convey subtle and mysterious psychological states that accompany a person undergoing a spiritual awakening, or witnessing a miracle. As in the works of both the earlier artists, the drama becomes an interior event.

In 1906, Tanner’s painting of Two Disciples at the Tomb won first prize at the Art Institute of Chicago’s 19th exhibition of American painting.. In it, Peter, the older man points to himself as if saying “Oh my God,” while the younger apostle John raises is head straining to with expectancy to see fulfillment of Jesus’ promise with the Resurrection. Light is strategically placed on the whitened necks against dark clothing, and the glow of their bony faces radiate a sudden awareness of the miraculous event of Christ’s Resurrection. They’re the faces of simple men, whose faith has saved them.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Three Marys, 1910 Fisk University, Nashville, TN 42″ x. 50″ |

The Three Marys is a particularly beautiful portrait of women as they see the light in front of Jesus’ tomb and that he has risen from the dead. The witnessing of a miracle is a profound spiritual event. Each woman has a slightly different psychological response. Like many of Rembrandt’s paintings, The Three Marys is nearly monochromatic, with blue as the primary color. He explained the intent of his paintings, “My effort has been to not only put the Biblical incident in the original setting, but at the same time give it the human touch….to try to convey to the public the reverence and elevation these subjects impart to me.” It seemed that as time went on, the blues get stronger and stronger in his paintings.

|

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson, 1893

Hampton University, Hampton, VA |

|

|

Actually Tanner’s best know paintings are The Banjo Lesson, 1893, at Hampden University and The Thankful Poor, 1894, in a private collection. He painted them on return to the United States and based them on memories from travel in North Carolina. Instead biblical stories, these paintings are scenes of everyday life. Yet they have a religious significance in their contemplative spirit and the suggestion of humility. The Banjo Lesson has two sources of light, an unseen window and an unseen fireplace or stove to the right. The glow of light shows that he was familiar with Impressionism and applied some of its diffusive, scattered light it.

Tanner traveled extensive to the Middle East and into the Islamic world. Trips to Egypt and Palestine in 1897 and 1898 may have given him inspiration for the settings in his paintings. After 1900, he developed a looser style, with more tonalism and the possibility of becoming more poetic.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, Abraham’s Oak, 1905, Smithsonian American Art Museum |

As we may expect, the city of Philadelphia has a substantial collection of his work, particularly where he studied, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The Smithsonian American Art Museum has a large collection of his works also. I particularly like Abraham’s Oak, which can be read as a pure landscape painting. Also fairly monochromatic, the painting reflects the Tonalist style prevalent in the United States at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. Tonalist landscapes are moody, evocative, contemplative and spiritual. He combines the underlying beauty in nature with a symbolic oak, the place Abraham staked out for his people as the Jewish patriarch.

Like the great early 19th century artist Eugene Delacroix, Tanner was fascinated by North African subjects and themes. (I see Delacroix’s influence in the vivid colors and the way he treated the floor patterns in The Annunciation.) He went to Algeria in 1908 and Morocco in 1912. The Atlas Mountains of Morocco are said have been inspiration a late painting, The Good Shepherd, also in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Figures became smaller, but faith is still his driving force. The unification of subject with landscape has increased. There’s a huge precipice these sheep could fall down, but their loving shepherd protects them. According to Jesse Tanner, his son, the artist believed that “God needs us to help fight with him against evil and we need God to guide us.” He lived to be 79, dying in 1937.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Good Shepherd, c. 1930 Smithsonian American Art Museum |

(I have seen only one exhibition of his paintings at the Terra Museum of American Art, back around 1996 and the work mesmerized me.) An exhibition in Philadelphia two years ago attempted to bring Tanner the recognition due to him. Here’s a professor’s review of the exhibit which also traveled to Cincinnati and to Houston.

There may be reasons apart from racism as to why he is not more famous in America. The United States lacks a tradition of religious painting and doesn’t easily embrace it. Furthermore, art historians celebrate artists who are innovators, those who bring art forward. Although Tanner was painting at the time of Picasso, Matisse, Kandinsky, Klee and O’Keeffe, he was not strongly affected by their trends of change. He stayed true to himself and in that way, he is a prophet of his faith rather than a prophet of the avant-garde.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Mar 23, 2014 | 19th Century Art, American Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Art Institute of Chicago

|

| Abbot Handerson Thayer, Winged Figure, 1889, The Art Institute of Chicago |

It may be the dreamer in me who is so attracted to the winged paintings of Abbott Handerson Thayer. The first of his paintings that I fell in love with was Winged Figure. above, at the Art Institute of Chicago. I’ve always admired the loose simplicity of the Grecian style of clothes, even before studying Greek art. However, what appeals most to me is the sense of security and peace this figure has as she sleeps, protected and held by the curve of her wing. Her leg and golden garment are strong and sculptural, but it’s not clear if she’s on the ground or on a cloud.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Angel, 1887, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of John Gellatly Mary, the artist’s daughter, posed. |

After moving to Washington, I found that Thayer is represented well in the nation’s capital. Angel of 1887 is a very young figure, and Thayer’s daughter Mary served as the model when she was 11. She’s frontal, symmetric, quite pale and white. She may or may not be in flight. Thayer is probably the premier American painter of angels, a Fra Angelico or a Luca della Robbia in paint. He gives them an idealized beauty and paints in a pristine Neoclassical style, as well as Europeans did.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, A Winged Figure, 1904-1913, The Freer Gallery of Art,

Smithsonian Institution Gift of Charles Lang Freer. The model is the

artist’s daughter, Gladys |

One of the winged figures at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art wears a laurel wreath. More rigid than his other angels, she faces us frontally with the geometry of a Greek column. Her face is severe, too, and she doesn’t quite touch the ground. Daughter Gladys was his model. (The Freer Gallery of the Smithsonian has published an explanation of the Winged Figures collected by Charles Lang Freer.)

Thayer’s preference for painting winged figures was not entirely religious. His interest in naturalism started as a 6-year old living near Keene, New Hampshire, when he began the avid study of birds and nature. However, his obsession with painting winged figures, angels and innocent children may have something to do with the fact that two of his children died unexpectedly in the early 1880s. That so many of his figures gained wings may represent hopes he had for coming to terms with loss.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Virgin, 1892-93,

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution Gift of Charles Lang Freer

(The artist’s children, Gladys, Mary, Gerald) |

|

|

|

|

He painted his three remaining children over and over again, and three of these paintings are in the

Smithsonian American Art Museum. In

Virgin at the Freer Gallery of Art, the oldest Mary faces us frontally walking in a pose similar to the

Nike of Samothrace. Although she doesn’t technically have wings like the Nike of Samothrace, the clouds behind her become large, white wings. Mary is an icon in the center who boldly holds and leads the younger sister and brother. She is noble and unflappable but moves swiftly. The younger children are strong, too, and do not smile. Their hair flies in the wind and the ground they walk on is hazy. Above all, they’re innocent. (These two younger children, Gladys and Gerald, also became painters.)

Understandingly, there was some intense melancholy surrounding he and his wife for some time. In 1891, his wife died, too. Thayer may be sentimental, but the paintings of his children would suggest he wanted them to be strong, triumphant and prepared for any event.

|

| Abbott Handerson Thayer, Roses, 1890, oil on canvas 22 1/4 x 31 3/8 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly |

Thayer was a superb painter of other subjects. He also did portraits, landscapes and still lives, which can be found on the Smithsonian’s website. An exceptional still life at Smithsonian American Art Museum, Roses, demonstrates his incredible skill. He manages to be highly detailed with the leaves and blooms but spontaneous and expressive for the vase and background. The color is somewhat muted, but the texture is strong. The style of his still lives compares well to Edouard Manet’s textured still lives and the pristine beauty Henri Fantin-Latour’s still lives. Like the highly skilled academic painter Bouguereau, he seems to be able to combine the best of the great 19th century styles: Neoclassicism, Realism and the emotional or dreamy qualities of Romanticism.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Mount Monadnock, 1911, 22 3/16 x. 24 3/16 “

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC |

The other great style of the period was Impressionism, which captured the fleeting qualities of light and colors. While Thayer may not be categorized as an Impressionist, he should be added to the list of marvelous snow painters. His best scenes of snow come from the area near where he lived in Keene and in Dublin, New Hampshire. In the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s Mount Monadnock, 1911, Thayer captured some of the beautiful scenery surrounding this mountain very familiar to him. There are vivid blues, purples and reds in this snow and the lights on the mountain top are brilliant. There’s a small, horizontal string of light coming across the ground to separate trees from mountain.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Monadnock No. 2, 1912,

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution. Gift of Charles Lang Freer |

He repeated the composition over and over, as Impressionists did. Mount Monadnock, 1904 and Monadnock No. 2, 1912 are in the Freer Gallery of Art. The snow topped mountain is also brilliant and even whiter in the painting of 1912. Touches purplish-gray suggest how cold it must have been. The trees are dark however, a definite force of nature. Thayer knew Impressionistic techniques and had lived in France, but he was also an artist who wanted to find some solidity and permanence in the world, even as it will change and be gone. He painted Winter Dawn on Monadnock in 1918, now in the Freer, too. There were less pine trees at this time, but the radiant pinks of dawn pervade the scene on the left.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Winter Dawn on Monadnock, 1918, The Freer Gallery of Art,

Smithsonian Institution Gift of Charles Lang Freer. |

Who can see and understand illusion in nature better than an artist? In 1909, he and his son, Gerald Handerson Thayer, wrote a major book on protective coloration in nature, Concealing and Coloration in the Animal Kingdom: An Exposition of the Laws of Disguise. He ascertained that in shadow birds or animals become darker to be hidden, but naturally turn lighter in sun. Another naturalist, former President Teddy Roosevelt, scoffed at his ideas and they were not accepted. However, he tried to share his ideas with the American government during World War I.

|

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Stevenson Memorial, 1903, 81-7/16 x 16 1/8 “

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC Gift of John Gellatly |

Thayer made as a memorial, above, to author Robert Louis Stevenson, someone he deeply admired but did not know. His first idea was for the memorial was to paint his three children, in honor of Stevenson’s book,

A Child’s Garden of Verses. He changed his mind, and a winged figure sits on a stone marked VAEA, the spot in Samoa where Stevenson is buried.

Thayer memorialized Stevenson, but what about his salvation? In 2008, the Smithsonian did a documentary film about him, Invisible: Abbott Thayer and the Art of Camouflage. Apparently his ideas about camouflage are more readily accepted now than they were in his time. Doesn’t his reputation as a painter deserve wide recognition, too? While keeping a foothold here on earth, his winged figures suggest that humans have the potential to transcend the hard life and fly above our limitations.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments