by admin | Apr 28, 2010 | Architecture, Sicily, The Greek World

The gigantic Temple of Olympian Zeus, Agrigento, was damaged by earthquakes before completion. This new statue, a flying bronze, echoes the temple’s fallen state. The wing overlaps and seems to touch a huge Doric capital to the right of the middle.

I was recently in Sicily to view mainly the ancient Greek sites. My camera broke and thankfully Kelli Palmer is letting me share her pictures of Agrigento, a city known for the beauty of its golden limestone.

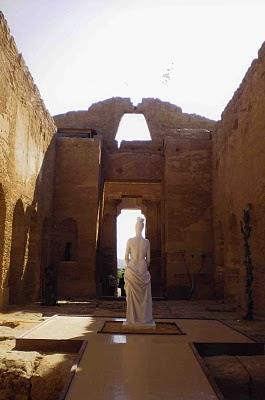

The Temple of Concord in Agrigento is one of the best preserved Greek temples standing today, probably due to the fact that it was used as a church in the Middle Ages. Right now contemporary sculpture is on display there and at the other temples in Agrigento. The combination of antique/modern — though not always successful — is particularly well done at this site because it does not detract from the ancient architecture while displaying the new work effectively. The sculptures seem to be made for this purpose.

A nude comfortably “bronzes”herself on the

porch of a 5th century BC Doric temple. It is

not known to whom the temp le wasdedicated

le wasdedicated.

Bronze hands reach upward, perhaps

expressing aspirations appropriate to

either church or temple. The arches date from the middle ages. The medieval builders cut arches into the walls, changing the ancient temple’s “cella”

into a church’s nave.

The modern marble figure, draped in a fashion reminiscent of the Venus de Milo, is far more sensual than a cult statue to Demeter, Persephone, Aphrodite or even the Christian Mary would have been in a religious building. But it stands harmoniously in this room which had been converted into a church’s nave in the 6th century. The relationship of a church‘s nave to its side aisles is similar to the relationship of an inner temple (the cella) to the outer colonnade.

by admin | Apr 8, 2010 | 19th Century Art, Hokusai, Landscape Painting, Nature, Printmaking, Van Gogh

Jean-Francois Millet, The Gust of Wind, 1871-73, National Museum of Wales

Jean-Francois Millet, The Gust of Wind, 1871-73, National Museum of WalesIt’s disappointing that the Corcoran exhibition, From Turner to Cezanne, had to be taken down early as a precaution over environmental concerns……I was counting on going Friday, April 9, three days after it abruptly closed. What am I missing? A spectacular collection from the National Gallery of Wales, little-known paintings of well-known artists that are seldom seen in the US………………… Torrents of Rain and Gusts of Wind…..

Vincent Van Gogh, Rain, Auvers, 1890, from the National Museum of Wales

Vincent Van Gogh’s suns, stars and flowers from sunny Provence express the intensity he experienced in the South of France. But in May, 1890, he moved north of Paris to Auvers-sur-Oise and painted Rain, Auvers in July. This painting conveys a heavy impact of rain with Van Gogh’s uncommon ability to combine actual texture of the paint itself with the tangible, tactile sense of objects painted. I really wanted to see Rain, Auvers to experience the downpour. Exaggerated or not, Van Gogh has the power to create a reality that makes us feel its presence more keenly. But the rain in this painting, deliberate gashes to the canvas surface, warns of a downpour more powerful than rain, the artist’s impending doom–he shot himself July 29th.

Even more than the Van Gogh, I was also looking forward to seeing paintings by Daumier and Millet, two mid-19th century French painters who are often overlooked, particularly in their gifts of great draftsmanship. Van Gogh seems to have admired them. One of Millet’s paintings from this Davies Collection at the National Museum of Wales is The Gus t of Wind, 1871-73. Millet conveys the full fury of a storm in the countryside. He captures the birds, leaves and branches with jagged, undulating brushstrokes. Along with the wind, his tree is uprooted and the birds, man (a shepherd whose sheep can barely be seen) and flock scatter in a fury, as the luminous colors of daylight poke through the background.

t of Wind, 1871-73. Millet conveys the full fury of a storm in the countryside. He captures the birds, leaves and branches with jagged, undulating brushstrokes. Along with the wind, his tree is uprooted and the birds, man (a shepherd whose sheep can barely be seen) and flock scatter in a fury, as the luminous colors of daylight poke through the background.

It is commonly understood that Van Gogh’s paintings of The Sower were inspired by Millet’s The Sower. No doubt Van Gogh knew many paintings by Millet and shared his appreciation for man’s connection to the land. He adopted Millet’s expressive lines, but thickened the contours and turned up the volume on color. Brandon, one of my students, was amazed to discover the wind that Van Gogh captured in The Olive Orchard, now on view in the Chester Dale Collection at the National Gallery of Art. Certainly Millet was one of Van Gogh’s most inspiring teachers, along with the Japanese artist Hiroshige, whose woodcuts gave Van Gogh the motif of diagonal cuts for rain.

In May and during

most of the summer, this exhibition travels to Albuquerque Museum of Art in New Mexico. However, while the O’Keeffe exhibition remains at the Phillips until May 9th, its worth seeing the weather photographs of Alfred Stieglitz and comparing them to paintings about weather.

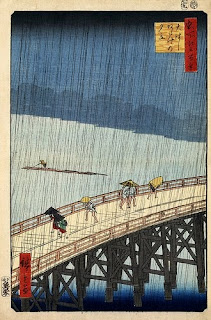

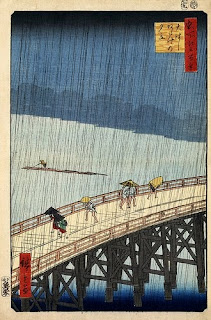

Ando Hiroshige, Rain Shower on Ohashi Bridge, 1857woodcut, at the Library of Congress. The rain, treated like gashes in the wood, influenced the gashes in “Rain,Auvers”

Van Gogh, The Olive Orchard, 1889, Chester Dale Collection,N ational Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

ational Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

detail, The Gust

of Wind, shows

how Millet’s lines influenced Van Gogh

by admin | Mar 6, 2010 | Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Lorado Taft

Before many monuments arrived on the national Mall in Washington, DC, the Adams Memorial in Rock Creek Cemetery was a major tourist attraction in the capital city. Because of its fame, I decided to visit it. I compared this monument to a tomb by Lorado Taft in Chicago, because I have always been quite moved by Taft’s Solitude of the Soul at the Art Institute of Chicago.

The Adams Memorial is a seated bronze figure with an androgynous face and deep, textured drapery. Augustus Saint-Gaudens completed it in 1891. Its green patina and mottled effect beautifully contrast with the speckled pink granite base and block designed by architect Sanford White. By comparison, Lorado Taft’s sculpture, erected in 1909, is starker; it takes the memorial concept further into 20th century abstraction.

Henry Adams, a 19th century historian and novelist, commissioned the Adams Memorial after his wife, Clover Hooper Adams, committed suicide in 1885. An amateur photographer of some note, Clover had suffered from depression before swallowing potassium cyanide, a chemical used in developing her photographs. Saint-Gaudens planned and executed the sculpture over 5 years. He loosely based the statue on Clover’s appearance, the iconic qualities of Buddhist statues and the grandeur of Michelangelo, particularly his Sibyls on the Sistine Ceiling, striving to capture an eternal presence in a figure that will never be alive to Adams, or us, again.

Saint-Gaudens entitled this work the The Mystery of the Hereafter and the Peace of God that Passeth Understanding, but the public called it “Grief,” a term Henry Adams never accepted. Adams, a grandson and great-grandson of US Presidents, was buried here when he died in 1918.

As I see it, the statue expressed Henry Adams’ need to come to terms with his wife’s death, an event about which he avoided speaking or writing. Yet the loss deeply affected him and whether there was guilt, regret or other unresolved feelings, he seems to have used the monument to make peace with those feelings. The intention was

to express a state of being which is neither joy nor anguish. The memorial avoids ideas about judgment and the hereafter, but evokes concepts of the divine feminine. Adams visited this grave statue often, but never met the state of peace the image portrays. (Yet the powerful female spirit appears to have influenced him long afterwards, as revealed in his books, The Education of Henry Adams and Mont Saint-Michel and Chartres.)

to express a state of being which is neither joy nor anguish. The memorial avoids ideas about judgment and the hereafter, but evokes concepts of the divine feminine. Adams visited this grave statue often, but never met the state of peace the image portrays. (Yet the powerful female spirit appears to have influenced him long afterwards, as revealed in his books, The Education of Henry Adams and Mont Saint-Michel and Chartres.)

The bronze figure, its face and strong hands are powerfully reminiscent of Michelangelo. The drapery is very heavy, but the woman’s face is not covered. She raises an arm and hand to intercept the veil, emphasizing that face. The eyes appear closed at first glance, but are actually open, looking downward. An earthly existence is vanishing but still present, as Henry Adams tried to keep her. And she is present to us in a timeless way, since the Saint Gaudens’ statue tries to avoid the finality of loss so pervasive in the statues of Lorado Taft.

Eternal Silence

Eternal Silence is the appropriate name Lorado Taft gave the grave marker of Dexter Graves in Graceland Cemetery, Chicago. A heavily draped bronze figure pulls his robe over his mouth, snuffing out his presence in the world. Note that a hand deliberately covers the mouth, in contrast to the Adams’ figure whose hand opens the veil like a curtain to reveal a face. Here the individual portrait is completely irrelevant; he is representative of an eternal truth, the finality of a life. Eyes are closed and, like most of the face, they are blackened.

Taft prefers broad, bold simplified shapes in sculpture, as opposed to the Adams Memorial’s more nuanced drapery folds. The bronze’s patina is a light green, in contrast to the black face. A nose pops out under the hood–also green. It’s spooky. No wonder many tales about ghosts have come from those who have visited the statue. For the record, Dexter Graves died in 1844, after he had come to Chicago from Ohio with 12 other founding families of the city in the 1830s. He built a hotel in Chicago and his son Henry commissioned the monument in 1907.

The statue and sky reflect behind into black granite, the

same material used in the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial. Taft simplified the outer garment, barely suggesting a large masculine physique underneath. The figure stands erect, his silencing complete.

same material used in the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial. Taft simplified the outer garment, barely suggesting a large masculine physique underneath. The figure stands erect, his silencing complete.

Taft — like Michelangelo and Rodin — was committed to using the human figure to express the greatest truths as he saw it, even if his ideas were quite abstract.

by admin | Feb 10, 2010 | Art and the Environment, Lorado Taft

The Black Hawk Memorial stands nearly 50 feet tall and rises on a 77 foot bluff above the Rock River in Oregon, IL. It pays homage to the Chief of the Fox and Sauk tribes who fought against the United States in the War of 1812. Lorado Taft designed the statue in 1908, long after the memory of this chief — who had controlled the region of the Mississippi and Rock Rivers until the 1830s — had vanished.

above the Rock River in Oregon, IL. It pays homage to the Chief of the Fox and Sauk tribes who fought against the United States in the War of 1812. Lorado Taft designed the statue in 1908, long after the memory of this chief — who had controlled the region of the Mississippi and Rock Rivers until the 1830s — had vanished.

Taft sheathed him in a blanket and simplified his form to focus on the face. The main ingredient is concrete, an interesting contrast to the wild environment, and to the more radiant granite and bronze of tomb memorials. Using a hollow core and iron tie rods, Taft and his student John Prasuhn created a broad sweeping column for the body leading up to the sad, heroic face.

Black Hawk died in 1838 and Native American culture also died, a fact not lost on Taft when he chose a generalized face rather than a likeness of Black Hawk. Taft considered this statue is the Eterna l Indian, symbolizing grief on a monumental scale. The artist knew deep sadness continually resonates and he did not attempt to pacify its presence.

l Indian, symbolizing grief on a monumental scale. The artist knew deep sadness continually resonates and he did not attempt to pacify its presence.

Simultaneously, he was working on

Eternal Silence, a commission for Dexter Graves’ tomb 100 miles away in Chicago.

Black Hawk was Lorado Taft’s own inspiration on the site owned by Eagles’ Nest Art colony he had founded in 1898. When his funds ran short, the state of Illinois paid for the statue’s completion in 1911.

Chief Black Hawk lost his land and was forced to move to Oklahoma in 1831, a resettlement which made it

possible for Graves and 12 other founding families to move to Chicago from Ohio. The artist must have known this irony when he was creating the statues. The memory of Black Hawk looms much larger and more specific than the memory of Graves; he commands a part of the environment.

possible for Graves and 12 other founding families to move to Chicago from Ohio. The artist must have known this irony when he was creating the statues. The memory of Black Hawk looms much larger and more specific than the memory of Graves; he commands a part of the environment.

Lorado Taft possessed a grand vision–equal to Black Hawk’s, for his students and art, but his reputation as a sculptor seems to be regional. An influential writer and teacher at the Art Institute, he made a large Fountain of Time near the University of Chicago, The Blind at the University of Illinois in Urbana, and the Columbus Monument at the Union Station in Washington. An online group follows his work.

by admin | Jan 6, 2010 | Art and Science, Greater Reston Arts Center, Rebecca Kamen

Never having studied High School Chemistry, I am fascinated by how sculptor Rebecca Kamen has taken the elemental table to create a wondrous work of art. The beautiful floating universe of Divining Nature: The Elemental Garden–recently shown at Greater Reston Area Arts Center (GRACE)–is based on the formulas of 83 elements in chemistry. Its amazing that an artist can transform factual information into visual poetry with a lightweight, swirling rhythm of white flowers.

According to Kamen, who teaches art at Northern Virginia Community College in Alexandria, she had the inspiration upon returning home from Chile. After 2 years of research, study and contemplation, she built 3-dimensional flowers based upon the orbital patterns of each atom of all 83 elements in nature, using Mylar to form the petals and thin fiberglass rods to hold each flower together. The 83 flowers vary in size, with the simplest elements being smallest and the most complex appearing larger. The infinite variety of shapes is like the varieties possible in snowflakes; their whiteness and uniformity of material connect them, but individually they are quite different.

One could walk in the garden and feel a mystical sensation in the arrangement of flowers, as intriguing as the “floral arrangement” of each single element. After awhile I discovered that the atomic flowers were installed in a pattern based upon Fibonacci’s sequence. Medieval writer Leonardo Fibonacci and ancient Indian mathematicians had discovered the divine proportion present in nature. This mystical phenomenon explains the spirals we see in nature: the bottom of a pine cone, the spirals of shells and the interior of sunflowers among other things. Greeks also created this pattern in the “golden section” which defines the measured harmony of their architecture. Kamen wanted to replicate this beauty found in nature and enlisted the help of an architect, Alick Dearie, to create the 3-D spatial arrangement.

Kamen likened her flowers to the pagodas she had seen in Burma. However, there is an even more interesting, interdisciplinary connection. Research on the Internet brought Kamen to a musician, Susan Alexjander of Portland, OR, who composes music derived from Larmor Frequencies (radio waves)emitted from the nuclei of atoms and translated into tone. Alexjander collaborated, also, and her sound sequences were included with the installation. Putting music and art together with science mirrors the universe and it is pure pleasure to experience this mystery of creation.

This installation is now in storage, but hopefully it will be exhibited again during the International Year of Chemistry, 2011. In the meantime, there are few videos online that can be found on youtube searching the artist’s name.

le wasdedicated.

le wasdedicated.

same material used in the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial. Taft simplified the outer garment, barely suggesting a large masculine physique underneath. The figure stands erect, his silencing complete.

same material used in the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial. Taft simplified the outer garment, barely suggesting a large masculine physique underneath. The figure stands erect, his silencing complete.

possible for Graves and 12 other founding families to move to Chicago from Ohio. The artist must have known this irony when he was creating the statues. The memory of Black Hawk looms much larger and more specific than the memory of Graves; he commands a part of the environment.

possible for Graves and 12 other founding families to move to Chicago from Ohio. The artist must have known this irony when he was creating the statues. The memory of Black Hawk looms much larger and more specific than the memory of Graves; he commands a part of the environment.

Recent Comments