by Julie Schauer | Feb 25, 2014 | Byzantine Art, Cathedral of Hildesheim, Christianity and the Church, Exhibition Reviews, Metalwork, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mosaics, National Gallery of Art Washington, The Middle Ages

Archangel Michael, First half 14th century tempera on wood, gold leaf

overall: 110 x 80 cm (43 5/16 x 31 1/2 in.) Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens

Gold radiates throughout dimly-lit rooms of the National Gallery of Art’s exhibition, Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Art from Greek Collections. Some 170 important works on loan from museums in Greece trace the development of Byzantine visual culture from the fourth to the 15th century. Organized by the Benaki Museum in Athens, it will be on view until March 2 and then at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles beginning April 19. The National Gallery has a done a great job organizing the show, getting across themes of both spiritual and secular life spanning more than 1000 years. The exhibition design is masterful and includes a film about four key Greek churches. The photography is exquisite and provides the full context for the Byzantine church art.

There are dining tables, coins, ivories, jewelry and other objects, but it’s the mosaics which I find most captivating, and this exhibition allows a close-up view. Their nuances of size and shape can be closely observed here, but not in slides or in the distance. Byzantine artists gradually replaced stone mosaics with glass tesserae, painting gold leaf behind the glass to portray backgrounds for the figures. It was the Byzantines created these wondrous images by transforming the Greco-Roman tradition of floor mosaics to that of wall mosaics.

|

| Van Eyck, St John the Baptist, det-Ghent Altarpiece |

|

|

New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art recently hosted another exhibition of the Middle Ages, “Treasures from Hildesheim,” works from the 10th through 13th centuries from Hildesheim Cathedral in Germany. Even though Greek Christians of Byzantine world officially split from Rome in the 11th century, the two exhibitions show that the art of east and west continued to share much in terms of iconography and style. Jan Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, from the 15th century, contains a Deesis composed of Mary, Jesus and John the Baptist, in its center, proving how persistent Byzantine iconography was in the West. That altarpiece shows the early Renaissance continuation of imagining heaven as glistening gold and jewels.

Church architecture evolved very differently however, with the Latin church preferring elongated churches with the floor plan of Roman basilicas. The ritual requirements of the Orthodox Church resulted in a more compact form using domes, squinches and half-domes. Fortunately, the National Gallery’s exhibition has a lot of information about Orthodox churches, their layout and how the Iconostasis (a screen for icons) divided the priests from the congregation.

|

| Reliquary of St. Oswald, c. 1100, is silver gilt |

Both cultures re-used works from antiquity. In the East, the statue heads of pagan goddesses could become Christian saints with a addition of a cross on their foreheads. In the west, ancient portrait busts inspired gorgeous metalwork used for the relics of saints, such as the reliquary of St. Oswald, which actually contained a portion of this 7th century English saint’s skull. Mastering anatomy, perspective and foreshortening was not as important an aim as it was to evoke the glory and golden beauty of heaven as it was imagined to be. The goldsmiths and metalsmiths were considered the best artists of all during this period in the west.

|

Mosaic with a font, mid-5th century Museum of

Byzantine culture, Thessaloniki

Photo source: NGA website |

|

|

|

Perhaps the parallels exist because many artists from the Greek world went to the west during the Iconoclast controversy, spanning most years from 726 to 843. Mosaic artists from the Byzantine Empire peddled their talents in the west, particularly in Carolingian courts of Charlemagne and his sons. From that time forward certain standards of Byzantine representation, such as the long, dark, bearded Jesus on the cross. While we seem to see these images as either icons or mosaics in Greek art, they become symbols in the west, often translated into sculptures of wood, stone or even stained glass.

An interesting parallel of the two exhibitions is the early Byzantine fountain, a wall mosaic of gold, glass and stone in the NGA’s exhibition, which compares well to the 13th century Baptismal font from Hildesheim, showing the Baptism of Christ. The font mosaic is from the Church of the Acheiropoietos in Thessaloniki. It is thought to emulate the fountains and gardens of Paradise. One can visualize of the context in which the fragmentary mosaic was made by watching the film in the exhibition, which shows another wondrous 5th century church in Thessaloniki, the Rotonda Church.

|

A Baptismal Font, 1226, is superb example of Medieval

metalwork from Hildesheim Cathedral. |

The exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum had a life-size

wooden statue of the dead Jesus, dated to the 11th century, originally on a wood cross, now gone. Wood carvers out of Germany were masters of emotional expression. In the iconic

Crucifixion image in the Greek exhibition, a very sad Mary and Apostle John are grieving at the side of Jesus. It’s poignant and emotional, with knit eyebrows, tilted heads and a profoundly felt grief.

|

| Golden Madonna is wood covered in gold, made for St. Michael’s Cathedral before 1002 |

|

The iconographic image of the Theotokos, a Greek type is normally a rigid, enthroned Mary who solidly holds her son, a little emperor. The format expresses that she is the throne, a seat for God in the form of Baby Jesus. From Hildesheim, there is a carved statue which dates to c. 970, carved of wood and covered with a sheet of real good. Both heads are now missing. At one time the statue was covered with jewels, offerings people had given to the statue. In the west, this type became common, called the sedes sapientaie, but the origin is probably Byzantium.

Although heaven is more important than earth, and God and saints in heaven are more powerful than humans, sometimes medieval artists have been capable of revealing the greatest truths about what it’s like to be a human being. In the icons, there is great poignancy and beauty in the eyes. At times the portrayal of grief is overwhelming, as we see on an icon of the Hodegetria image where Mary points the way, the baby Jesus but knows He will die. On the reverse is an excruciatingly painful Man of Sorrows.

|

| Icon of the Virgin Hodegetria, last quarter 12th century, tempera and silver on wood, Kastoria, Byzantine Museum. On the Reverse is a Man of Sorrows |

The Metropolitan exhibition of course could not bring the two most important works from Hildesheim, the bronze relief sculptures: a triumphal column with the Passion of Christ and a set of bronze doors for the Cathedral. Completed before 1016, I often think of the figures on the relief panels on those doors as one of the most honest works of art ever created. As God convicts Adam of eating the forbidden fruit, Adam crosses his arm to point to Eve who twists her arms pointing downward to a snake on the ground. We may laugh because God’s arm seems to be caught in his sleeve as he points to Adam. Though this medieval artist/metalsmith (Bishop Bernward?) may not have understood anatomy and perspective, he understood how easy it is for humans to pass the blame and not take responsibility for their actions.

|

| The Expulsion, before 1016, detail of bronze door, St. Michael’s, Hildesheim |

Medieval artists in both the Greek and Latin churches are normally not known by name. After all, their work was for God, not for themselves, for money or for fame.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 23, 2014 | Bruges, Film Reviews, Jan Van Eyck, Leonardo da Vinci, Manet, Michelangelo, Renaissance Art, The Ghent Altarpiece

|

Jan Van Eyck, Mary, part of the Deesis composition, detail

of The Ghent Altarpiece in St. Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium, c. 1430

photo source: Wikipedia |

The Monuments Men is a true story about saving cultural artifacts in war. George Clooney has done a great job acting and directing this film which has an important message about art, what it means for us and the efforts some would go to save culture. One woman who played a huge part in saving art is shown and Cate Blanchett played that role with depth and finesse. An all-star cast doesn’t guarantee good reviews, but I often disagree with movie reviewers. Matt Damon, Bill Murray and Jean Dujardin star in the movie, too.

|

Tourists in front of the Ghent Altarpiece in recent times. A film, The Monuments Men,

explores its theft and recovery in World War II. Photo source: daydreamtourist.com |

The star monument is Jan Van Eyck’s The Ghent Altarpiece, an example of one of the earliest oil paintings. (If students had seen the movie, they would have known it on a test, but the film was released only 5 days earlier and we had a snowstorm) In fact, the last missing part of the Ghent Altarpiece, was the panel of Mary, mother of Jesus from a Deesis grouping (an iconographic type western painters adopted from the eastern Orthodox Church). She is exquisitely beautiful and radiant. Van Eyck’s ability to visualize heavenly splendor and beauty in paint is astounding. I appreciate the film for showing how big the altarpiece actually is, and how a polyptych, of many panels, needed to be broken up into its parts to be moved. Actually, I wonder if Van Eyck and the patrons knew that using the polyptych format, rather than just a three-part triptych, would have its advantages in the time of war. Actually that painting has been the victim of crime 13 times and stolen 7 times, including the times of the Reformation, Napoleon and World War I.

|

Michelangelo’s Bruges Madonna, the last work to be

recovered, is under glass at the Church of Our Lady

in Bruges. Photo source:Wikipedia |

The other star monument is Michelangelo’s Bruges Madonna, a free-standing sculpture the artist did shortly after The Pieta. It was the last and most precious piece to be found. The film makes an important point about the British man who insisted on protecting it during the war. I’m honored to have seen both monuments in their current homes and thank the determined people who sacrificed so much to do this for posterity. (I also love that the movie gives goes into the Hospital of Sint-Jans in Bruges and gives good views of the medieval cities of Bruges and Ghent, even in the night time. Thanks for acknowledging to what these places represent to earlier European culture.

Much of the film is about uncovering the mysteries, as well as anticipating the need for protection. It has both comic and tragic elements, as we watch injury and death and the dangers that common to all war. Not all paintings were saved, however. Some works ended up in Russia after the war and are still there. Picassos and Max Ernst paintings, even in German hands, were determined to be decadent and burned. The movie showed a Raphael portrait of a young man that has never been found.

|

Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine, c. 1490, is a

portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, and an early work of Leonardo. It’s

in the Czarytorski Museum in Krakow Photo source: Wikipedia |

Among the paintings captured by the Nazis, saved and uncovered by the rescue team of Americans, French and English were: a Rembrandt portrait, a Renoir, a Van Gogh, Manet’s In the Conservatory and Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine which had been taken from Krakow, Poland. Most of these paintings were shown to be hidden in underground mines. I’ve checked a little bit into the history of each of these and found that the Leonardo had been hidden in a castle in Bavaria. The Nazis stole the Manet from a museum in Berlin, and it’s not clear to me why they would do that unless it was planned to be in Hitler’s own museum.

The movie may have intentional inaccuracies. It also looked like a poor replica of Leonardo’s Ginevre de’ Benci was in the movie, and I am not sure if that could be accurate. That painting, as far as I know, already had been in the Mellon Collection that became part of the National Gallery.

There is much more to the story, I know, because Italy was allied with Nazis during most of the war and those works of art needed to be protected, too. At the point of action where the movie had started, most of the works in France had already been protected. The Monuments Men deals mostly with works in Belgium and the Netherlands.

Robert Edsel wrote the book that is the basis for the movie. I certainly hope to read it now, as well as another followup book he published last year, Saving Italy.

|

| Edouard Manet, In the Conservatory, 1879, Altes Museum Berlin Photo: Wikipedia |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 1, 2014 | Exhibition Reviews, Fiber Arts, Folk Art Traditions, Greater Reston Arts Center, Local Artists and Community Shows, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Women Artists

|

Rania Hassan, Pensive I, II, III, 2009, oil, fiber, canvas, metal wood, Each piece

is 31″h x 12″w x 2-1/2″ It’s currently on view at Greater Reston Arts Center. |

There’s a revival of status and attention given to traditional, highly-skilled arts and crafts made of yarn, thread and materials. “Stitch,” a new show at Greater Reston Arts Center (GRACE), proves that traditional sewing arts are at the forefront of contemporary art, and that fiber is a forceful vehicle for expression. Meanwhile, the National Museum of Women in the Arts puts the historical spin on traditional women’s art in “Workt by Hand,” a collection of stunning quilts from the Brooklyn Museum which were shown in exhibition at their home museum last year.

|

Bars Quilt, ca. 1890, Pennsylvania; Cotton and wool, 83 x 82″;

Brooklyn Museum,

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. H. Peter Findlay, 77.122.3;

Photography by Gavin Ashworth,

2012 / Brooklyn Museum |

Quilts are normally very large and utilitarian in nature. To some historians, American quilts are appreciated as material culture with possible stories of the people who made them, but they also have some vivid abstract patterns and strong color harmonies. Their bold geometric shapes vary and change with different color combinations. Quilting is a folk art since it is a passed down tradition, and the patterns may seem stylized and highly decorative. Yet there is room for tremendous variation, creativity and individual style.

Within the United States there are important regional folk groups whose quilts have a distinctive style, like the Amish quilt, above. Amish designs can have a sophisticated abstraction deeply appreciated during the period of Minimal Art of the 1960s and 1970s. The exhibition outlines distinctions and also shows styles popular at certain times, including Mariners’ Knot quilts around 1840-1860, the Crazy Quilts of the Victorian period and the Double Wedding Ring pattern popular in the Midwest after World War I.

|

| Victoria Royall Broadhead, Tumbling Blocks quilt–detail, 1865-70 Gift of Mrs Richard Draper, Brooklyn Museum of Art. Photo by Gavin Ashworth/Brooklyn Museum. This silk/velvet creation won first place in contests at state fairs in St. Louis and Kansas City. |

, |

|

|

|

|

One beautifully patterned quilt is from Sweden, but the rest of them are made in the USA. The patterns change like an optical illusions when we move near to far, or when we view in real life or in reproduction. There’s the Maltese Cross pattern, Star of Bethlehem pattern, Log Cabin pattern, Basket pattern and Flying Geese pattern, to name a few. The same patterns can come out looking very differently, depending on the maker. An Album Quilt has the signatures of different people who worked on different squares. We know the names of a handful of the quilting artists.

|

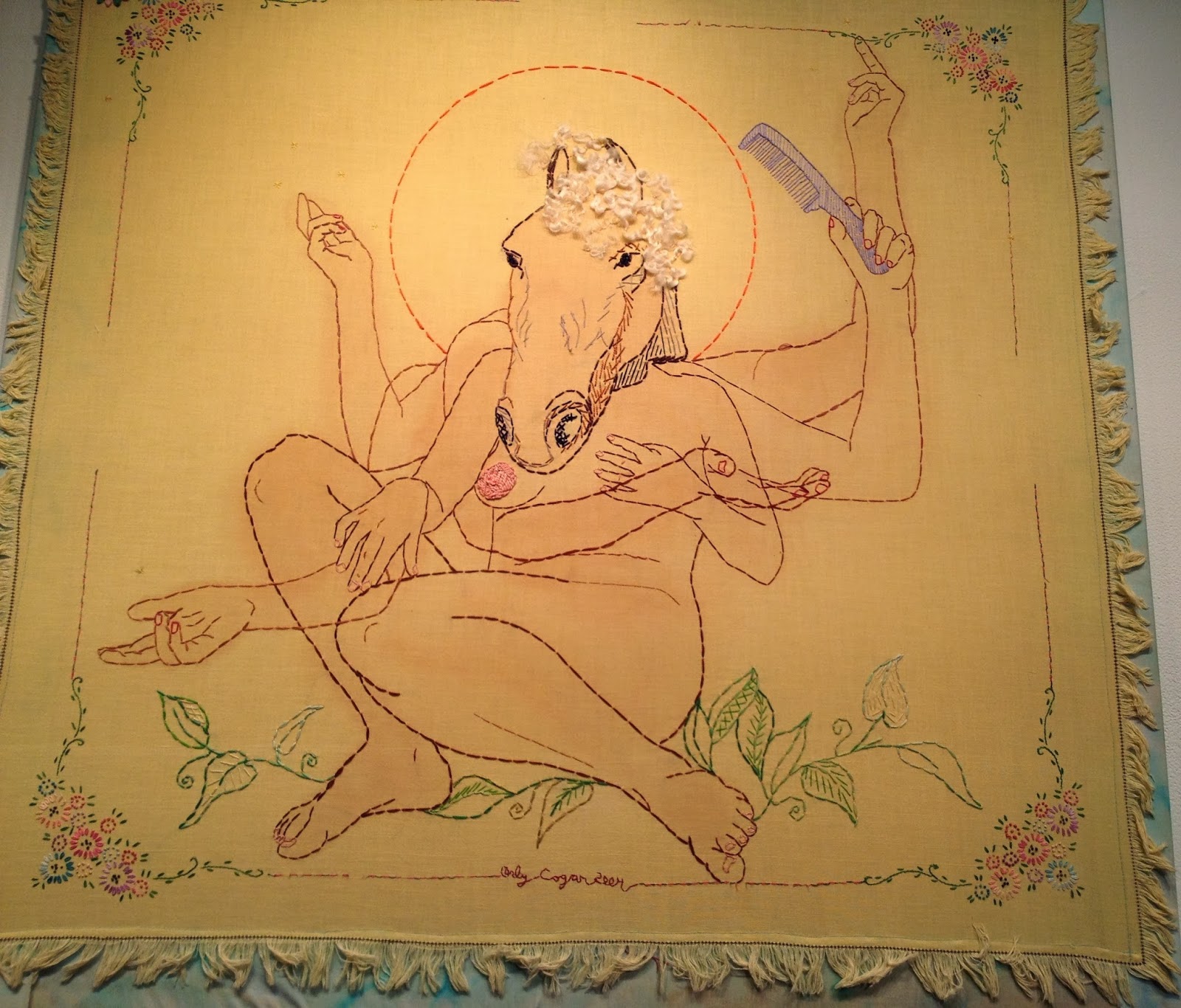

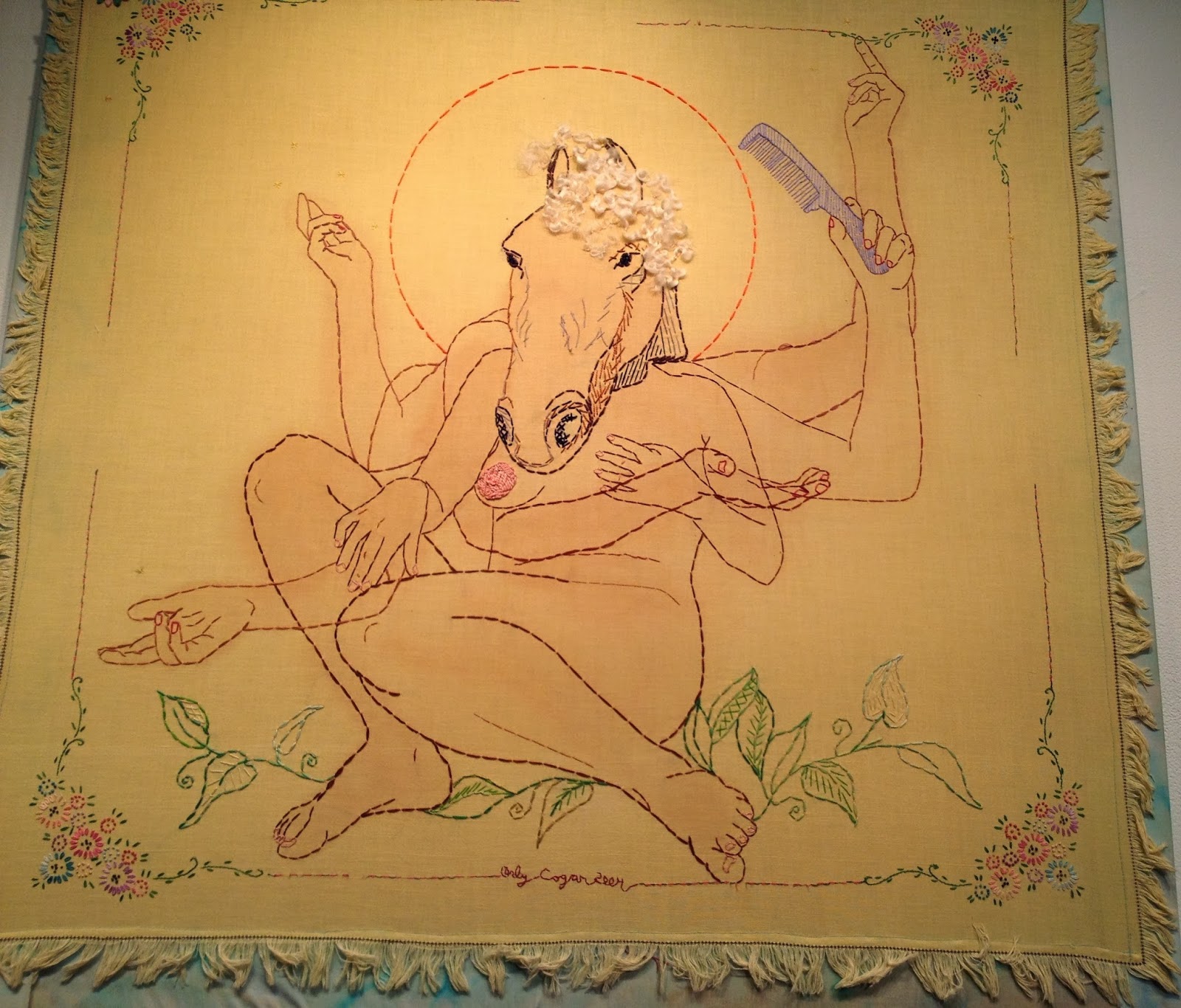

Orly Cogan, Sexy Beast, Hand stitched embroidery

and paint on vintage table cloth, 34″ x 34″ |

While most of the quilts featured in the exhibition were made by anonymous artists, the Reston exhibition includes well-known national figures in fiber art, such as Orly Cogan and Nathan Vincent. Cogan uses traditional techniques on vintage fabrics to explore contemporary femininity and relationships. Her works appear to be large-scale drawings in thread. She adds paint and sews into old tablecloths. I loved the beautiful Butterfly Song Diptich and Sexy Beast, a human-beast combination with multiple arms, like the god Shiva. Vincent, the only man in the show, works against the traditional gender role, crocheting objects of typically masculine themes, such as a slingshot.

|

Pam Rogers, Herbarium Study, 2013, Sewn leaves, handmade

soil and mineral pigments, graphite,

on cotton paper, 22″ x 13-1/2″ |

Most “Stitch” artists are local. Pam Rogers stitches the themes of people, place, nature and myth found in her other works. Kate Kretz, another local luminary of fiber art, embroiders in intricate detail, expressing feelings about motherhood, aging and even the art world.

Kretz’s own blog illuminates her work, including many of the pieces in “Stitch. The pictures there and the detailed photos on an embroidery blog display in sharper detail and explain some of her working methods.

Often she embroiders human hair into the designs and materials, connecting tangible bits of a self with an audience. Kretz explains, “One of the functions of art is to strip us bare, reminding us of the fragility common to every human being across continents and centuries.”

Kretz adds, “The objects that I make are an attempt to articulate this feeling of vulnerability.” Yet some of the works also make us laugh and chuckle, like Hag, a circle of gray hair, Unruly, and Une Femme d’Un Certain Age. Watch out for a dagger embroidered from those gray hairs!

|

Kate Kretz, Beauty of Your Breathing, 2013, Mothers hair from gestation

period embroidered on child’s garment, velvet, 20″ x 25″ x 1″ |

|

Suzi Fox, Organ II, 2014, Recycled

motor wire, canvas, embroidery hoop

12-1/2″ x 8″ x 1-1/2″ |

Kretz is certainly not the only artist who punches us with wit and irony, and/or human hair, into the seemingly delicate stitches. Stephanie Booth combines real hair fibers with photography, and her works relate well to the family history aspect alluded to in NMWA’s quilting exhibition. Rania Hassan is also a multimedia artist who brings together canvas paintings with knitted works. In Dream Catcher and the Pensive series of three, shown at top of this page, she alludes to the fact that knitting is a pensive, meditative act. She painted her own hands on canvases of Pensive I, II, III and Ktog, using the knitted parts to pull together the various parts of three-dimensional, sculptural constructions. She adds wire to the threads for stiffness, although the wires are indiscernible. Suzi Fox uses wire, also, but for delicate, three-dimensional embroideries of hearts, lungs and ribcages (right).

There’s an inside to all of us and an outside. Erin Edicott Sheldon reminds us that stitches are sutures, and she calls her works sutras. Stitches heal our wounds. “I use contemporary embroidery on antique fabric as a canvas to explore the common threads that bind countless generations of women.” Her “Healing Sutras” have a meditative quality, recalling the ancient Indian sutras, the threads that hold all things together.

|

Erin Endicott Sheldon, Healing Sutra#26, 2012, hand

embroidery on antique fabric stained with walnut ink |

In this way she relates who work to the many unknown artists who participated in a traditional arts of quilting. Like the Star of Bethlehem quilt now at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the traditional “Stitch” arts remind us to follow our stars while staying grounded in our traditions.

|

| Star of Bethlehem Quilt, 1830, Brooklyn Museum of Art Gift of Alice Bauer Frankenberg. Photo by Gavin Ashworth/Brooklyn Museum |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Jan 26, 2014 | Asian Art, Buddhism, Collage, Folk Art Traditions, Mandalas, Medieval Art, Mosaics, The Sackler Gallery of Art

|

Temporary floor mandala, flashed by light onto the floor

of the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery of Asian Art |

Mandalas, an important tradition in India, Nepal and Tibet have spread well into the West, or as some think, have always been in the West. The exhibition, Yoga: The Art of Transformation at the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery of Art, takes us into art and history surrounding the physical, spiritual and spiritual exercise of yoga. It’s the first exhibition of its kind. This is the last weekend of the show, featuring works of art in Hindu, Jain and Buddhist practice. Yoga hold some keys to mental and physical healing.

We’re led into yoga’s 3,000-year history by a series of light patterns flashed on the floor–patterns that are mandalas and have lotus patterns. (Lotus is also the name of a yoga pose.) After this weekend, they’ll be gone with the show, but that’s the spirit of mandalas, at least in the Tibetan tradition.

|

| Light Pattern on the floor of the Sackler Gallery of Asian Art forms a Mandala |

Mandalas have radial balance, because their designs flow radially from the center, somewhat like the spokes of a wheel. Traditional Buddhist monks in Tibet spend time together making mandalas of colored sand, working from the center outward using funnels of sand that form thin lines. Deities are invoked during this process of creation, following the same ancient pattern of 2,500 years. The creation is thought to have healing influence. Shortly after its completion, a sand mandala is poured into a river to spread its healing influence to the world.

|

| Chenrezig Sand Mandala was made for Great Britain’s House of Commons in honor of the Dalai Lama’s visit in May, 2008. Material: sand, Size: 7′ x 7′ Source of photo: Wikipedia |

|

|

|

Like the Buddhist Stupas which began in India, the Mandalas are microcosms of the macrocosm, or small replicas of the universe. Yantras are mandalas that are an Indian tradition which may have a more personal meaning. Their beautiful geometric designs can be highly efficient tools for contemplation, concentration and meditations. Concentrating on a focal point, outward chatter ceases and the mind empties to gain a window into truth. Making mandalas can be a powerful aid in Art Therapy.

|

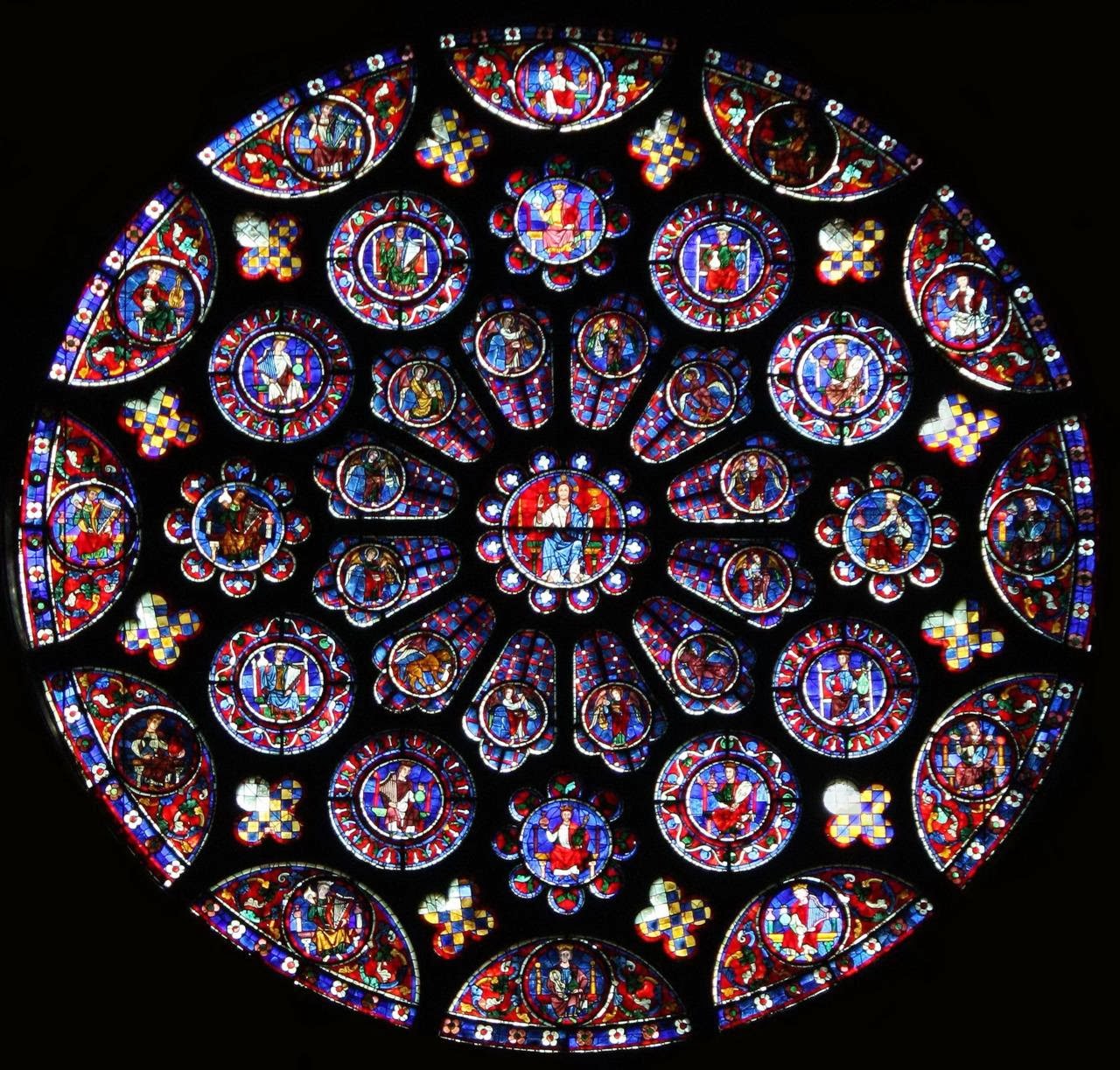

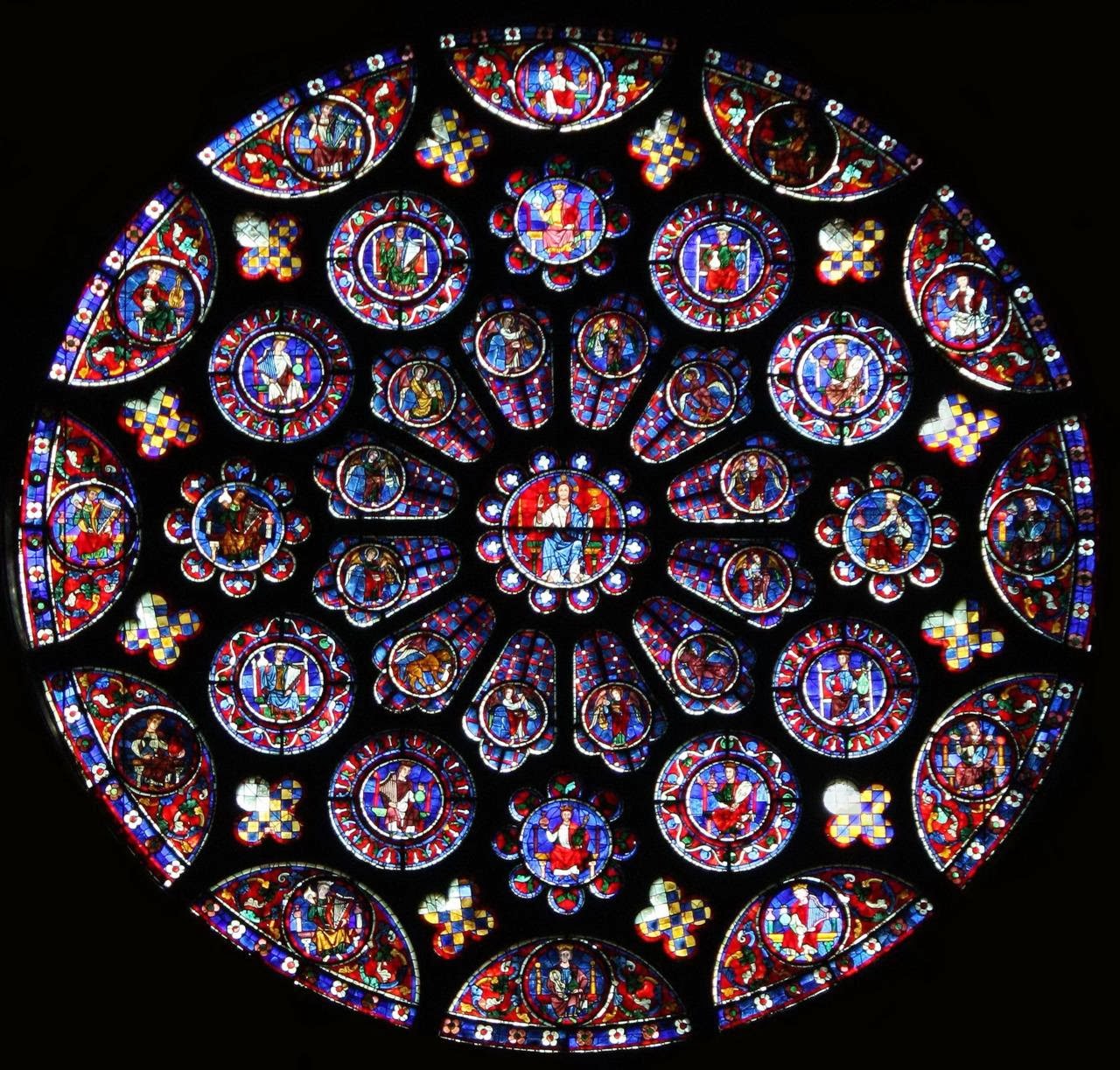

| North Rose Window of Chartres Cathedral, France, c. 1235 |

Circles, without a beginning or end, have an association with God and perfection. They’re an integral part of the design of Gothic Cathedrals, such as Chartres Cathedral and Notre-Dame of Paris which are among the most famous. Their patterns radiate out from the center, into rose patterns. I didn’t believe it when, years ago, a student mentioned they were inspired by Indian mandalas. The greater possibility is that spiritual wisdom comes from the same or similar sources.

|

Sri Chakra Mandala, ceramic tile, made by Ruth Frances Greenberg

17-1/4″ x 17-1/4″ x 1-1/4′ photo Lubosh Cech |

Artist Ruth Frances Greenberg makes ceramic tile mosaic mandalas in her Portland, Oregon studio, and sells them for personal and decorative use. Some are inspired by the Om symbol and by the home blessing doorway mandalas of Tibet. Others are inspired by the Chakras, the energy centers in ancient Indian tradition. The Sri Chakra Mandala has nine interlocking triangles and beautiful geometric complexity. It combines the basic geometric shapes of circle, square and triangle, and expresses powerful energies.

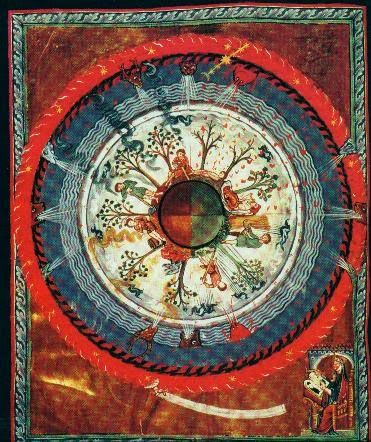

The circle within a square is common in many traditions, but in Indian art the openings of the square represent gateways. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, a study of perfection in human proportions, has a circle within a square. Medieval mystic, St. Hildegard of Bingen, a Doctor of Church, wrote music and created art in response to her visions. Wheel of Life is one of her many visions that were put into illumination in the mandala form, in the 12th century.

Chicago artist Allison Svoboda makes mandalas from a surprising combination of media: ink and collage. She explains, “The same way a plant grows following the path of least resistance, the quick gestures and simplicity of working with ink allows the law of least resistance to prevail….With this process, I work intuitively through thousands of brushstrokes creating hundreds of small paintings. I then collate the work…When I find compositions that intrigue me, I delve into the longer process of collage. Each viewer has his own experience as a new image emerges from the completed arrangement. The ephemeral quality of the paper and meditative aspect of the brushwork evoke a Buddhist mandala.”

|

| Allison Svoboda, Mandala, GRAM, 211–detail |

The 14′ by 14′ Mandala GRAM from the Grand Rapids Art Museum is a radial construction with many inner designs. Some of these designs resemble a Rorschach test, but infinitely more complicated.

The intricacies of the GRAM Mandala alternate and change as our eyes move around it. It’s like a kaleidoscope or spinning wheel. But a configuration in center pull us back in, reminding us to stay centered and whole, as the world changes around us.

|

| Allison Svoboda, Mandala, GRAM, 2011, Grand Rapids Museum of Art, in on paper, collaged 14′ x 14′ |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Jan 18, 2014 | Marc Chagall, Mosaics, Mythology, National Gallery of Art Washington

|

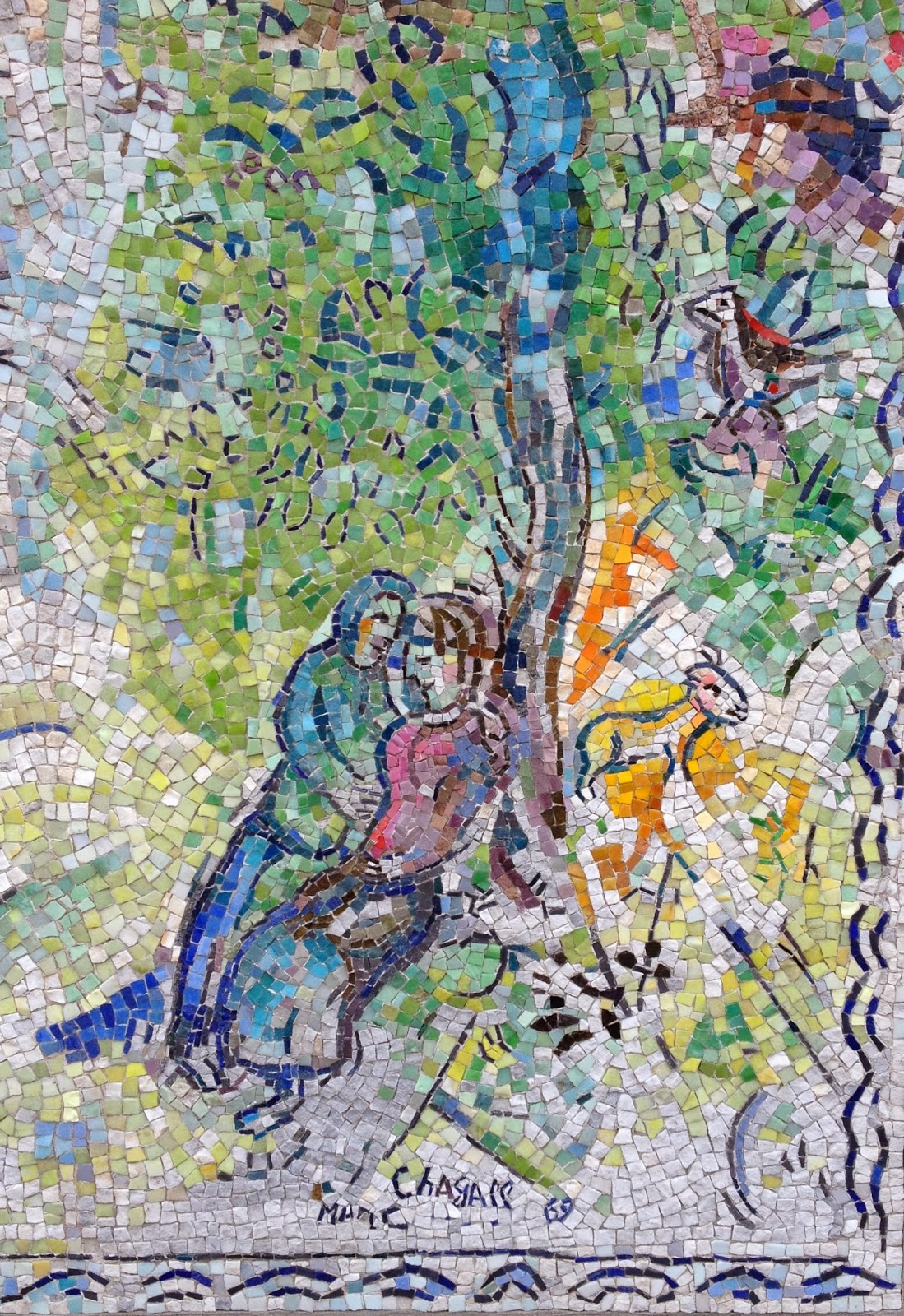

Detail – Marc Chagall, with Lino Melano, Orpheus, 1971, from the upper

right side–Pegasus, Three Graces, Orpheus

|

The nation’s capital city added a sudden burst of color this season in the form of Marc Chagall’s Orpheus, a glass and stone mosaic. It’s a 17′ by 10′ wall standing in the National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden, between 7th and 9th Streets, NW, Constitution Avenue and Madison Avenue. Evelyn Stephansson Nef, who died in 2009, donated it to the museum. (The composition is one of three new acquisitions in the National Gallery, a must-see along with a Van Gogh, a Gerrit von Honthorst and a loan of the Dying Gaul from the Capitoline Museum in Rome.)

The mosaic stands in the garden behind the restaurant, but in front of the heavily traveled Route 1. Fortunately, a lot trees shield it from view of the traffic, providing a reflective space for viewers. The sculpture garden is on the National Mall, but open only from 10-5 daily and 11-6 Sundays, except for an ice rink in winter which has longer hours.

Evelyn Nef and her husband, John Nef, were friends of the artist who was inspired after visiting them in 1968. The artist gave the mosaic to the couple back in 1971. For years, it was in the garden of their Georgetown residence, vaguely visible from the street. The National Gallery spent years preparing, repairing, moving and re-installing its 10 separate concrete panels, a process described in the Washington Post. The seams aren’t visible.

|

Detail, Marc Chagall, Orpheus, 1971. Here Orpheus

is crowned and holds his lyre. |

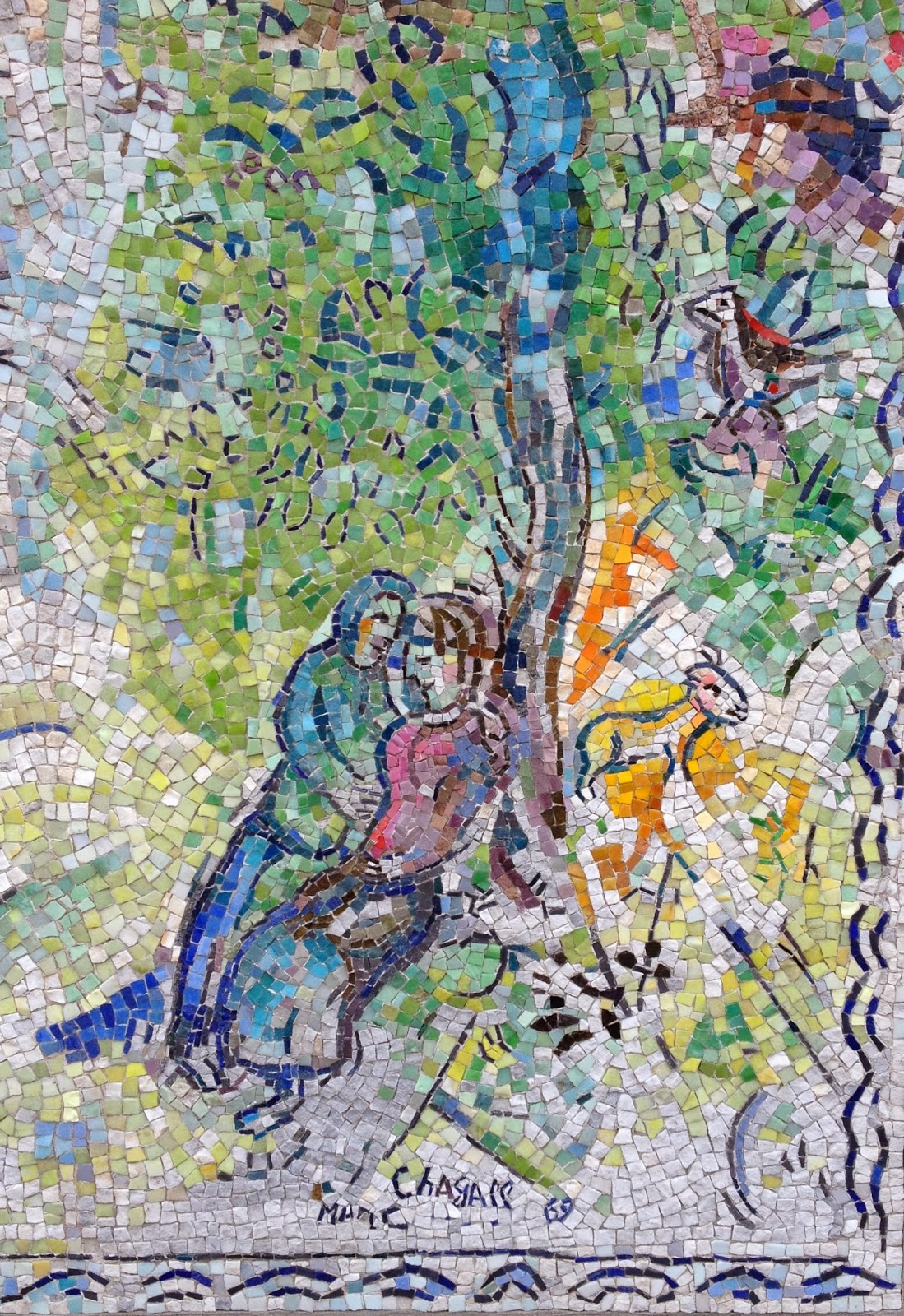

Chagall did the drawings for the composition in his studio back in France, and then hired mosaicist Lino Melano to complete it. Melano supervised installation which was finished in November, 1971. The artist returned at the time to see it. It was his first mosaic installed in the US. Afterwards, Chagall did the renowned Four Seasons mosaics for the First National Plaza in Chicago.

The composition has the spontaneity, verve and joy we can expect from Chagall. The execution, however, took a highly skilled Italian mosaicist who was steeped in the tradition. Melano used Murano glass, natural-colored stones and stones cut from Carrara marble. On close inspection, viewers can discern where there is glass: in the most brightly-colored passages, the shining blues, reds and radiant yellows. There is a touch gold leaf behind some of the glass, a technique inherited from the Byzantine mosaicists.

(For a good comparison, Byzantine mosaics are currently on view in the marvelous National Gallery Exhibition, Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Art from Greek Collections, until March 2, 2014.) Byzantine mosaics also combine stone cubes and glass cubes, called tesserae, but the tesserae are much, much smaller in Byzantine mosaics.

Melano wisely reserved the gold leaf for a few choice places, but only on Orpheus, his crown and his knee.

|

Detail, Marc Chagall, Orpheus, mosaic, 1971. Figures cross the ocean,

with an angel guide, the sun and mythological horse, Pegasus |

The god Orpheus is shown without his ill-fated mortal lover, Eurydice. Eurydice lost him because she disobeyed fate and dared to turn back and look at him while in the underworld. Chagall ignores the pessimistic part of the story. How then do we interpret what Chagall was trying to convey?

The other mythological figures are the flying horse Pegasus and the Three Graces. The winged-horse does not have feet, reminding me of the incomplete depictions of animals painted in the caves of southern France, near Chagall’s studio. Orpheus holds his lyre in a prominent position. Pegasus flies and Orpheus makes music while a little birdie flies. The Graces are not dancing here, but they remind us of our gifts and that grace is indeed possible. Chagall, who escaped Europe in the Holocaust, had a knack for putting a positive spin on events. He obviously chooses the highest potentials of human nature, while not exactly ignoring the negative.

|

| Detail, lower left corner with Chagall’s signature |

Of course the myth of Orpheus also conjures up images of the underworld. On the left, there is water where people are entering in groups and fishes are swimming. Could this be the River Styx of Greek mythology? Chagall said it referred to the groups of immigrants who crossed the ocean to get a better life. Above the river is a huge burst of sun. An angel flies triumphantly overhead, with open arms. The artist ignored the rules of perspective and foreshortening on this figure, reminding us that flight, or overcoming limitation, is indeed possible. He suggests that dreams can come true.

A dreaming couple on the bottom right hand side are happily in a paradise, under a tree. The artist’s signature is underneath. Chagall may have thought of himself with his wife, Bella. According to the National Gallery’s website, Evelyn Nef asked Chagall if this was her and her husband, John. He replied, “If you like.” There’s a border to the composition. Everywhere lines are curved, making this composition the image of life as a joyful journey, a graceful dance with much optimism.

|

Marc Chagall, Russian, 1887-1985, Orpheus, designed 1969, executed 1971, stone and glass mosaic

overall size: 302.9 x 517.84 cm (119 1/4 x 203 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

The John U. and Evelyn S. Nef Collection

2011.60.104.1-10 |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments