by Julie Schauer | Nov 20, 2013 | Archeology, Architecture, Christianity and the Church, Roman Art, The Middle Ages

|

A first century temple to Mars, or possibly Janus, near Autun (ancient

Augustodunum) in Burgundy may have inspired the large churches of this region

in the 11th and 12th centuries. Only a fraction of this building remains today. Here,

a family from the Netherlands had a picnic while climbing the ruin.

|

A movement to dot the landscape of Europe with large churches in the 11th and 12th centuries was fueled by deep Christian faith, but, initially, the important building technologies had inspiration from the remains of ancient, pagan buildings. The population surged at this time and the last invaders, the Vikings and Magyars, had settled down.

|

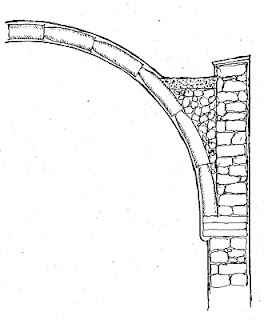

A transept of St. Lazare, Autun, built around 1120

has tall arches and a blind arcade like many

late Roman buildings. The rib vaults

vault are an innovation of Romanesque |

Romanesque is the name given today to that style of art, reflecting its common traits with Roman architecture: arches, barrel vaults and groin vaults. Although the library at the monastery of Cluny, in Burgundy, had a copy of the Roman architect Vitruvius’ treatise on architecture which described how to make concrete, the medieval builders did not use concrete. They looked at the stones around them, used their compasses and measures, and created a marvelous revival of monumental building. It was a time of pilgrimages and Crusades, and stone masons moved from place to place, spreading architectural ideas.

|

Porte d’Arroux is the best preserved of four gates

erected in Autun during Roman times. |

In the first centuries of Christianity, builders reused Roman columns, which were plentiful in the forums surrounding civic buildings of the ancient cities. Romanesque sculptors invented their own style of column capitals and used them to tell stories in sculpture. Even in monastery churches, Romanesque builders needed to allow for pilgrims coming to see relics and they built big. For the proportion of nave arcades to the upper levels of churches, the gallery and clerestory, they took some cues from Roman buildings, aqueducts and gates and made the upper levels smaller. At times, late Roman architecture of the 3rd and 4th centuries, which tended to be more organic and experimental than buildings from the Augustan age, probably served as models.

|

Porte St-Andre is one of the two Roman gates standing in Autun, Burgundy,

although much of it was restored in the 19th century. |

Outside of Autun, the remains of a temple to Mars or Janus, of Gallic fanum design, has magnificent high arches that reminded me of Arches National Park in Utah. Two Roman gates and the remnants of a Roman theater are in Autun, also. It’s surprising so much remains, because the city was sacked by both Saracens in the 8th century and Vikings in the 9th century. Because of the richness of the ruins, it’s not surprising that some of the greatest cathedrals from Romanesque times were built in the Burgundian region of east-central France: St. Lazare in Autun, Ste. Madeleine in Vézelay, St. Philibert at Tournus, and, above all, St. Pierre at Cluny. The church at Cluny remained the largest Christian church until St. Peter’s, Rome, was completed in the 17th century. Most of it was damaged during the French Revolution.

|

The Baths of Constantine, Arles

dated to the 4th century |

Further south, in Arles, the Baths of Constantine, built in the 4th century, may have inspired medieval builders. (It’s hard to know how much was built over it or covered up at the time.) It has clusters of bricks which alternate with limestone in forming the arches. This Roman decorative variation was sometimes imitated. The curved end and semi-dome of the “tepidarium” (warm bath) resembles the apse end of churches from the Middle Ages. In fact, curved exedrae, which are shaped like semi-circles, were ever present in all types of Roman buildings. Probably the best example of Roman vaulting techniques were seen in the theatre and an amphitheater in Arles, dating to the early empire.

|

The curved Roman exedra form of this

bath building was imitated in the curved

east end of Romanesque churches |

Nearby was a famous aqueduct, the Pont du Gard, with three rows of superimposed arches harmoniously proportioned like the two or three levels in the naves of Romanesque churches. In Nîmes, there was also a Roman tower, an amphitheatre, and a theatre that has vanished. The Maison Carrée in Nîmes, a famous Augustan temple, served as inspiration mainly because of its decorative details. The straight post-and-lintel construction did not offer practical solutions for the large size desired in the Romanesque churches. (In neoclassical times, Thomas Jefferson used the Maison Carrée as the model Virginia’s state capital building.)

Most art historians talk of the relationship between the design of triumphal arches and the facades of churches in Provence. Certainly the abundant decorative details of churches in Provence, including Saint Trophime in Arles, is in imitation of classical decorative motifs. This church and others in Provence had continuous bands for narrative sculpture, called friezes, as on classical buildings.

|

The layout of St.-Gilles-du-Gard near Nîmes, France, is often compared to

the design of Roman triumphal arches. The frieze is a continuous narrative in sculpture.

Additionally, the shape of the round tympanum and pilasters has parallels with the

so-called Temple of Diana, below left. |

|

In Nîmes, the remains on the inside of a 3rd

century Temple to Diana, may have inspired

the design of the tympanum and barrel vault,

standards for Romanesque church design

|

However, I note the similarity between St.-Gilles-du-Gard, in the Rhone delta, and the building traditionally considered a Temple of Diana in Nîmes, probably from the 3rd or 4th century. It provides a model for the shape of a tympanum, an important field for sculpture over the doorway of Romanesque churches. Only portions of the interior remain, with the beginning of a reinforced barrel vault, pediments and pilasters. It is easy to see how the shapes of Roman buildings determined some shapes in the churches and cathedrals. Certainly the doorways at St.-Gilles resemble three-part triumphal arches, like the Arch of Constantine or triumphal arch in Orange (see photo on bottom).

|

At St-Gilles-du-Gard, two heads look like Roman

portraits. One that grows out of a Corinthian capital

is dressed like a priest. A snake is approaching the

other head. Only an artist of the Middle Ages

could use classicism with so much wit and whimsy! |

When Romanesque builders took inspiration from ancient art and architecture, they added much of their own creativity and ingenuity. They began to make the arches taller, the vaults more elaborate and pointed, reflecting their borrowings from Islamic architecture during and after the Crusades. (One such Romanesque Church, which took in so many diverse influences, including sculpture in the style of Provence, is Monreale Cathedral, discussed previously on another page in this blog.)

|

The Triumphal Arch in Orange, France was a

richly ornamented, a trait carried over in the

Romanesque churches of Provence |

When it came to sculpture, they were very imaginative, whimsical and emotionally expressive of the religious zeal of a bygone age. At times, they re-used classicism in ways that would not have been acceptable at all, as in Sainte-Marie de Nazareth in Vaison-la Romaine.

Romanesque architecture developed very quickly and led to the Gothic style, which began in Paris around 1150 and spread almost everywhere within a century.

The Via Lucis website has the best and most comprehensive photographs and explanations of Romanesque art and architecture.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Sep 27, 2013 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Architecture, Erechtheion, Greek Art, Parthenon, the Acropolis

|

The Erechtheion is an Ionic building, with its porches going in different directions.

It commemorates the founding of Athens, with the contest between Athena and Poseidon |

Glistening white marbles which is seem to grow out of the hill form the picture on my mind of the Athens’ Acropolis, from what I’ve seen in textbooks. The city’s highest hill has been a wonder to the world for 2500 years, and a symbol of Greek civilization since ancient times.

|

One climbs the hill to get to the Propylaia, monumental gateway to the Acropolis.

A wide opening in the center allowed horse-drawn chariots

to enter. This view is from inside the hill. |

|

Although the Parthenon is

Doric, this column on the

ground was Ionic |

Yet, at any given time, so much on the Acropolis is in the process of restoration, covered up by scaffolds. I was there on the first day of June, which, unusually, was not a sunny day.

|

A view of the Acropolis ruins leads to another hill, capped

Athens Tower |

I was surprised to see that there are as many stones on the ground as there are against the skies. It appears that the archaeologists have carefully arranged, catalogued and labelled the stones with numbers to fit them into a puzzle which could locate and determine their placement in the past. I must confess to be a lover of ruins who finds them very dramatic and sees great beauty in their fallen state. Close-up views reveal the artfulness that goes into creating fine decorative designs.

Of course, the Parthenon is the best known, most beautiful and most perfectly proportioned of all Greek temples. Most of the building’s west end was hidden from view, while I was there. From a few angles it’s possible to see a good deal of its former glory.

|

| East end of the Parthenon from inside of the Acropolis |

|

The pediment on the left side of the east end, the heads of

horses pulling the chariot of the sun and a reclining god

are visible. These plaster casts replace the Elgin marbles. |

Unfortunately, the center of the Parthenon blew up and was lost for good in 1685, when the Ottoman Turks were using it as an arsenal and a Venetian cannon hit it. In 1804, Lord Elgin, British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, took most of its marble architectural sculpture and brought it to his home in Scotland. When he financial problems, he sold these originals, called the Elgin Marbles, to the British Museum, where they remain today. In some accounts, the marbles were being damaged and at risk of more damage under the Ottoman rule of the time.

However, there are plaster casts on the building, including sculpted horses and a reclining god (Dionysos or Heracles) on left side of the east pediment. These gives a great impression of how the the sculptures fit in under the roof. Replicas of the rest of the sculpture are on display at the New Acropolis Museum in Athens, completed in 2009. The museum’s display reveals fairly well how the large sculptural program related to the architecture.

|

Above a triglyph is a horse’s head on

the opposite side of the pediment

|

I was surprised to find out that a few of the

original square relief sculptures, called metopes, are actually in the Acropolis Museum.

One of these reliefs is particularly beautiful: Hebe and Hera, mother and daughter who sat among the gods and goddesses deciding the outcome of the Trojan War. Despite all the damage, the panel was recently restored. The drapery of the seated goddess, Hera, is so beautiful that we can sense the distinct folds of an undergarment as well as the outer clothing. Experts think that the Parthenon’s chief sculptor, Phidias, did this panel.

|

The Metope of goddesses Hebe and Hera

are among 4 metopes still in Athens |

|

|

There’s so much more history of construction and destruction. The classical building of 442-432 is actually a replacement for the earlier temple to Athena which was burned by the Persians in 480 BC. Many fine statues of young women (kore, called korai, plural) and young men (kouros, called kouroi, plural), which were buried after the Persian pillage, are on display at the museum. Besides the elegant Peplos Kore, there are many other less famous votive statues of women from the Archaic period. Despite the archaic stiffness of many of these sculptures, they are extremely beautiful. I also appreciated the beauty of the relief statues of Nike (victory) figures from the balustrade which had surrounded the Temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis, built after the Parthenon.

|

| The modern, recently-built Acropolis Museum, is set on an angle, but in an axis facing the Parthenon. The Theater of Dionysos, from the 4th century BC covers the hill, between the Parthenon and Acropolis Museum. |

We can see more of the Erechtheion, an unusual temple formed with slender porches reaching out on three different sides. Because of its tall, Ionic columns and the Porch of the Maidens, I found the Erechtheion the most impressive of all buildings on the Acropolis. The caryatids are replacements for the original statues.

|

The Erechtheion is an Ionic temple. Its decorative

details contrast with the simple Doric columns of the other structures |

The original statues can be seen from all sides in the new Acropolis Museum. A trip to that museum is a must for understanding the many stages of construction and destruction on the Acropolis, and for understanding the many building programs of the Acropolis. The Athenians had begun building their temple around 490 BC, before the Persians destroyed it. However, there are sculptures reflecting at least two even earlier temples to Athena, one from about 570 BC, and another dating around 520 BC. The stones of one of these temples are beneath the Erectheoion. Construction and destruction were constants in the lives of the ancient Greeks.

|

A view behind the Porch of the Maidens over to the long side of the Parthenon

reminds me that the Erechtheion stands over the stones of a giant Archaic temple,

an earlier templet to Athena, |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Sep 15, 2013 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Architecture, Greek Art, Knossos, Mythology

This summer I finally had the opportunity to go to Greece and see the sprawling Palace at Knossos. Actually, it’s not certain if this site was a palace, administrative center, giant apartment building, religious/ceremonial building, or all of the above. Yet it is so huge that, when discovered in 1900, archeologist Arthur Evans certainly thought he had found a true labyrinth where the legendary King Minos lived and kept his minotaur. The name Minoan for the Bronze Age people who lived in Crete from about 2000-1300 BC has stuck.

|

Covering 6 acres, the palace of Knossos and the surrounding city may have

had a population of 100,000 in the Bronze Age |

According to legend, the king of Athens paid tribute to King Minos by sending him 7 young men and young women who were in turn fed and sacrificed to the half-man, half-bull minotaur. Eventually, with the aid of Minos’ daughter and the inventor Daedalus, Theseus carried a ball of thread to find his way out and to slay the beast.

Although the art at Knossos doesn’t play out the precise myth, carvings and paintings found there involve imagery of bulls. Acrobats jumped and did flips over the animals’ horns, perhaps part religious ritual. It must have been an exciting but highly dangerous sport, and it’s easy to understand that as the story changed over time, later generations would envision a bull-headed monster in a spooky maze.

|

The palace at Knossos is on the hillside, about 5 kilometers from the sea. It was never fortified

Other, smaller palaces have been uncovered on the island. |

Could a prisoner escape without Theseus’ clever trick? Three or possibly four entrances to the palace are off-axis and may have appeared entirely hidden. The building also had windows, light wells, air shafts and ventilation. It was an engineering marvel. No wonder its architect Daedalus became a god to the Greeks. When I was there, it not only felt like a “labyrinth,” but also like “babel.” Its the only place I’d ever been where so many different, unfamiliar languages were being spoken at once. Despite the number of people, it never felt too crowded, because the palace covers six acres.

|

The downward taper of Minoan

columns is unusual but may have

religious significance. The capital

resembles the cushions of Doric

columns of Greece 1000 years later |

The building runs over 5 levels of twists and turns, on the hillside, not on top of a hill. It had 1300 rooms at one time and could have housed as many 5,000 people. There’s a large central courtyard, perhaps where crowds observed the bull-leaping sports. At least four other ancient maze-like palaces have been excavated on other parts of the island, but none as large as Knossos. It is thought that only 10% of Minoan Crete has been excavated and that bronze age Crete had 90 cities. I remember reading that Knossos had a population of at least 100,000 people around 1500 BC. Minoans traded with Egypt and Mesopotamia. Archaeologists have uncovered a Minoan colony in Egypt, Tel-el D’aba, and at Miletus in Turkey.

|

The North Entrance has a restored

fresco of a bull. Minoans were probably

the first to paint in fresco, on wet plaster |

Evans spent 35 years digging, researching and restoring the Palace of Knossos. The restoration reveals the Minoans’ unusual, downward-facing columns, with the narrowest parts on bottom. The earliest builders used the cypress tree and turned it over, so it wouldn’t grow.

There were both small frescoes and life-size frescoes, most of them now in the Archeological Museum in Heraklion, including the bull-leaping fresco. Since Egyptians painted in secco, on dry plaster, it’s believed that Minoans invented the fresco technique of painting on wet plaster. Colors such as blue, red and yellow ochre are very vivid. Generally Minoans painted with a freer and more organic style than the artists of Egypt and Mesopotamia, and often had more naturalistic depictions. However, whenever men or women are found marching with erect stiff postures, it’s conjectured that they functioned as priests and priestesses partaking in the religious rituals. There’s a famous bull-leaping fresco in the local museum.

|

| La Parisienne from Knossos |

|

|

|

Archeologists of today would not take as much liberty and restore as extensively as he did. While Evans pieced together restorations of the palace based on the remnants and shards, he also used his knowledge to restore what is missing. Personally I appreciate that his reconstruction fills in the blanks for us, giving an idea of the size and grandeur of the palace. Also, there’s a great deal to speculate as to what it may have been like to live there. It seems that grains, wine and olive oil may have been milled and pressed at the palace, and also stored in huge pithoi (giant vases) under the floor.

The word labyrinth originates from the labrys, a double-axe related to the double horns of the bull. The language used at the time the first palace was built, around the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, has not yet been deciphered. A second language which appeared at Knossos after mainland Greeks took over the palace after 1500 BC has been translated and is related to the classical Greek language

|

The life-size Prince of Lilies was thought by

Archeologist Arthur Evans to be a priest.

Lilies are common in Minoan imagery. |

All the inscriptions on cylinder seals are commercial records and inventories. Besides myth, the art and artifacts are the best way to figure out the story of these people. Only about 10 percent of the ancient Minoan sites have been excavated. Although the contents of the Archeological Museum of Heraklion, near Knossos, is well known and published, the beautiful pottery and artifacts from the museum of Chania, Crete’s next largest city, have not been published. Getting outside of the cities and into the countryside leaves the impression that the rural life really hasn’t changed too much in 1000 years.

|

The grand staircase at Knossos spans 5 levels. The layout of rooms is organic around a

central courtyard. What seems to be a haphazard arrangement may reflect

building and rebuilding after earthquakes. |

Certain things that date to the Mycenaean takeover of the palace include the Throne Room. Amazing, when the room was discovered, the gypsum throne was intact. Evidence points to the suggestion that the palace had to be abandoned all of a sudden, because of a fire, natural disaster or invasion. Even if this culture eventually went into oblivion for a few hundred years, when the Greek culture re-emerged around the 8th century BC, the Greeks culture retained so much of the Minoan heritage in its art and myth. The myths of the minotaur, Minos, Europa, Theseus, Daedelus and Icarus involve Crete, but so does the story of Zeus who was said to be born in Crete.

|

The Throne Room was found with oldest throne in

Europe, dating to Mycenaean occupation of Crete, around

1450-1400 BC. Evidence shows people had fled suddenly. |

Knossos has a theatre right outside the palace. Performances took place at the bottom of two seating areas set perpendicular to each other, rather than at the end of curved seating area as in later Greek theaters. The ancient Minoans also gave the world two important inventions, indoor plumbing and the potter’s wheel. Wouldn’t it be something if some of the first great Greek literary masterpieces also had an origin here, 1000 years earlier?

Occupation of the palace ended sometime between 1400 and 1100 BC. In the classical era Crete was never as important as Athens, though it is clear that much of what formed later Greek culture came from Crete. A settlement re-emerged in Knossos during Roman times, but during the Middle Ages the population shifted to the city of Heraklion, about 4-5 miles away.

|

| An area outside of the palace has two sets of seats set at a perpendicular angle. Acoustics indicate it was a theater. |

|

|

|

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Mar 6, 2011 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Mosaics, Roman Art, Sicily

In the huge Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Armerina, Sicily, a girl is can be seen through the corridor………………..not one, but the room has 10 of these bikini girls engaged in some athletic activities. They are made of pieces of finely cut stone, set into mortar for a smooth finish on the floor. Mark Schara took these photos of the largest series of floor mosaics in the Roman Empire.

In the huge Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Armerina, Sicily, a girl is can be seen through the corridor………………..not one, but the room has 10 of these bikini girls engaged in some athletic activities. They are made of pieces of finely cut stone, set into mortar for a smooth finish on the floor. Mark Schara took these photos of the largest series of floor mosaics in the Roman Empire.  Their games include the discus throw, weight lifting and ball tossing. One with a palm and crown may be a winner.

Their games include the discus throw, weight lifting and ball tossing. One with a palm and crown may be a winner.

From the mosaics in ancient Sicily we can trace the art of stone floor mosaics, backwards. Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Amerina, covered by a landslide in the 13th century but now uncovered, has the largest group of extant mosaics from the Roman world. The cut marble stones decorated floors, not walls, of the palace. It is not known who built or owned the huge villa in the early 4th century, but it may be connected to the emperors, or gladiators in the late Roman Empire. There are several mosaics of giant figures and animals, representing diverse subjects like the Labors of Hercules, hunting and children fishing. One of the most surprising subjects is a group of young women, bikini girls. The floors of the entire villa are covered with remarkable picture puzzles.

Also at Villa Romana del Casale is the Room of Fishing Cupids. The children appear quite young and have curious markings on their faces .

At nearby Morgantina, three excavated homes have floor mosaics from the 3rd century BCE, some 500 years earlier than the Villa in Piazza Armerina. Above is a mosaic in the House of Ganymede, perhaps the earliest mosaic cut into cubes. Ganymede is being abducted by Zeus’ eagle, and the Greek key pattern in the border creates an optical illusion of shifting perspective patterns.

At nearby Morgantina, three excavated homes have floor mosaics from the 3rd century BCE, some 500 years earlier than the Villa in Piazza Armerina. Above is a mosaic in the House of Ganymede, perhaps the earliest mosaic cut into cubes. Ganymede is being abducted by Zeus’ eagle, and the Greek key pattern in the border creates an optical illusion of shifting perspective patterns.

Although we normally associate mosaics with the Byzantine wall mosaics in churches, the Hellenistic Greeks and Romans used them extensively. From Hellenistic times, three homes with mosaics have been excavated in Morgantina. Of special note is a mosaic in the House of Ganymede, made of marble and very finely executed, suggesting the wealth of central Sicily before the Roman takeover in 211 BCE. The House of Ganymede may, in fact, have the earliest mosaics found to be cut into squarish tesserae, the standard “tesselated” form for Roman and Byzantine mosaics. The best guess for a date is 250 BCE. It may copy a painting.

An animal mosaic from the Punic island of Mozia is the earliest known floor mosaic, perhaps from the early 4th century BCE. Composed of only gray, black and white pebbles, it was made before the famous pebble mosaics of Pella, Greece, from about 300 BCE.

An animal mosaic from the Punic island of Mozia is the earliest known floor mosaic, perhaps from the early 4th century BCE. Composed of only gray, black and white pebbles, it was made before the famous pebble mosaics of Pella, Greece, from about 300 BCE.

The oldest known floor mosaic is in Mozia, the small Punic island adjacent to Marsala, Sicily, which was conquered by Greeks in 397 BCE. In the House of the Mosaic, there is a floor carpet of real and imagined animals composed of black, white and gray pebbles. It lacks color and looks rough compared to later mosaics of both pebble and cut stone. Its border patterns — the Greek key, palmettes and waves — definitely look Greek. Does it come from shortly after the Greek conquest of 397 BCE? or even earlier?

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 25, 2011 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Architecture, Greek Art, Mythology, Sicily

In Selinunte, Sicily, the remains of several Greek temples from the 6th- 5th century

In Selinunte, Sicily, the remains of several Greek temples from the 6th- 5th century

BC can reveal much about temple construction, although they fell to Carthaginian invasions and earthquakes not long after their building. Architect Mark Schara,

with his good eye for detail, took almost all of these photos.

Temple E has most of its outer colonnade, the peristyle, restored.Classical harmony is apparent in the rhythm of fluted columns, continuing up into the triglyphs raised to the sky.

.

But many of the capitals have fallen. On the ground level, we can appreciate their large scale.

But many of the capitals have fallen. On the ground level, we can appreciate their large scale.

Temple F was badly damaged. Much of the white stucco facing for the fluted limestone column on right is still visible.

Temple G, below, was the largest of the 7 temples of Selinunte, the ancient city of Silenus.

This temple had columns about 54 feet tall. Here, we see the columns were made of individual segments called drums, each of which are 12 feet high

This temple had columns about 54 feet tall. Here, we see the columns were made of individual segments called drums, each of which are 12 feet high.

The overturned capitals, echinus on top of the abacus, has an 11′ diameter. Here, the abacus and echinus were carved in one piece, unlike above at Temple E.

At the time of destruction, not all of the capitals had been fluted. Thus we

know that the temple was never completed

Nearby in Agrigento, the ancient city called Akragas, had a series of ten temples in the Valley of the Temples.

The Temple of Concord is one of the best preserved Doric temples.

It had been converted into a church in the early Christian period.

In the 8th -3rd centuries BCE, Sicily was a battleground between Greeks who settled 3/4 of the island and Carthaginians who settled the western portion; then it became the target of Roman conquest.

Though only a small portion of the peristyle remains, the

Though only a small portion of the peristyle remains, the

Temple of Hera was in better condition than most of these temples

which fell victim to Carthaginian destruction, then earthquakes.

But an even taller temple to Olympian Zeus would have been the largest of Doric Greek temples, the height of a 10-story building; it was incomplete when the disaster struck.

Construction began in 480 BCE and was still in progress when it was decimated in 407 BCE. The Telemon or Atlas figures whose bent arms support the architravemay in fact represent Carthaginian prisoners who had been made to build the temple.

Construction began in 480 BCE and was still in progress when it was decimated in 407 BCE. The Telemon or Atlas figures whose bent arms support the architravemay in fact represent Carthaginian prisoners who had been made to build the temple.  But even these giants, who appear to have held up the building, have fallen,

But even these giants, who appear to have held up the building, have fallen,

struck down by the Carthaginians who conquered Akragras.

Only a replica of one of the ruined giants remains on the site.

Ancient Akragas may have had 200.000 people in the 5th century BCE.Today we witness the fallen giant as a symbol of human pride grown too large,

Ancient Akragas may have had 200.000 people in the 5th century BCE.Today we witness the fallen giant as a symbol of human pride grown too large,

and, consequently, fallen.Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 21, 2011 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Architecture, Sicily

(Thanks to Mark Schara for the use of his photographs)

The North Baths of Morgantina, in east central Sicily, date to the 3rd century BCE and may in fact represent the earliest dome that has been excavated in the ancient Mediterranean world. Like everything in the buried settlement of Morgantina, it was built before the Roman conquest in 211 BCE. This new evidence suggests that Hellenistic Greeks, not Romans, invented the first dome. However, unlike the concrete used by Romans to make domes, the construction material would have been terra cotta tubes found on the site; the sizes and formation of these tubes suggest they were used to make a domed space.

Public baths were a staple of the ancient towns and cities. Morgantina was a small settlement and the dimension of its baths are modest. Yet the roofing of the North Baths structure appears very significant. Two oblong rooms and one circular room were found to have curved ceilings made of these interlocking tubes, held together inside and out by plaster. They would have formed perfect arches when fit together, and each arch when placed in parallel alignment with other arches forms either a barrel vault or dome. There were two barrel vaulted rooms and one with a dome.

This method was also used in

the Roman baths of North Africa in the 3rd century CE, while builders in Rome were using concrete. The Morgantina baths are at least 4 centuries earlier than the others of this technique and predate Roman concrete vaults and domes by about a century.

Interlocking cotta tubes made in the Hellenistic settlement of Morgantina were

fit into each other to form arches. Arches placed adjacent to each other could form a dome, above, or barrel vaults, with masonry reinforcement as shown on the right.

Although some excavation began in the early 1900s, archeologists identifed Morgantina as the archeological site in 1958 using coins. The place had been described by Strabo and some early Roman writers, but it was abandoned by the end of the first century CE. Originally a Sikel settlement, it was occupied by Greeks in the 5th century BCE, conquered by Rome in 211 BCE and consequently taken over by Spanish mercenaries of Rome. In addition to baths, Morgantina has an agora, a theatre, graneries, an ekklesiesterion, several sanctuaries, homes with mosaics and two kilns which have been excavated.

An overview of Morgantina reveals the Greek theatre and other excavation structures.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments