by Julie Schauer | Sep 8, 2011 | Conceptual Art, Contemporary Art, Exhibition Reviews, National Gallery of Art Washington, Video Art

Electronic Superhighway, 1995,a gift from the artist to the Smithsonian American Art

Electronic Superhighway, 1995,a gift from the artist to the Smithsonian American Art

Museum, Washington. This 49-channel installation is neon, steel and other electrical parts.In the Tower: Nam June Paik is at the National Gallery of Art until October 2nd. This Korean-American artist introduced the realm of tv/video art with sculptures made of televisions in 1966. The exhibit encompasses themes and ideas important to art of the last 50 years.

His last video sculpture made in 2005, Ommah (mother in Korean) uses a 100-year-old boy’s robe, hanging like a cross, with a projection of Korean-American girls at play, linking past and present. It is in the National Gallery’s permanent collection

To fully appreciate his work one must see the exhibition in the museum’s East Wing. His art is about tv/video, a relatively new medium in visual art. A room of Paik’s drawings accompany the exhibition and help the viewer understand his thought process. One of the most interesting takes us back to the 60s culture; it’s a drawing of the Pan Am domestic routes represented by bunny-eared TV icons connected by red lines. He seems to have projected that many networks of our lives have been influenced by TV, and perhaps have changed us.

Paik, who died in 2006, is credited with bringing this medium into the realm of contemporary art. Compared to other video artists (there are many today!), Paik is certainly a multimedia artist who thought more in terms of how television and its relatives can be incorporated into art, rather than end and aim of the art itself.

One Candle, Candle Projection, 1988-2000 candle, candle monitoring device, closed circuit camera, projectors, distribution amplifier, and 5″ color monitor, dimensions variable Nam June Paik Estate

One Candle, Candle Projection, 1988-2000 candle, candle monitoring device, closed circuit camera, projectors, distribution amplifier, and 5″ color monitor, dimensions variable Nam June Paik Estate

© Nam June Paik Studios, Inc. 2010

He used knowledge of technology and contemporary art to reflect on traditional cultural identities. He was vastly concerned with bringing together aspects of the past with the present. One Candle, One Projection, 1988-2000, is the centerpiece of the exhibition, and one can only grasp its power by experiencing it in the large, dark exhibition room. The dim lighting of the viewing space is ideal for the meditative concepts here. A single candle is lit everyday and a multiplicity of projections move, flicker and interact as the viewer is invited to watch. Time, or the passage of time, is of the essence.

In seeing the Paik exhibition, I appreciated this modern artist’s ability to think about the contemporary aims of the society within which he was working and then make a statement. Personally, he disliked the passivity of television but could not ignore its influence on culture. In an ironic play on this notion, his Standing Buddha with an Outstretched hand is a meditation on the act of watching, using a traditional bronze sculpture as a backdrop to the modern technology. Time passes, but the statue stays the same, and Paik effectively made a statement on the meaning of television in life while connecting it to traditional meditation. Paik was trained a a classical musician and was friends with John Cage.

Three Eggs, 1975-1982

video installation with closed circuit camera, Sony KV-4000 Color Television Receiver, emptied Sony KV-4000 Color Television Receiver, and 2 hen eggs

Nam June Paik Estate © Nam June Paik Studios, Inc. 2010

Like 20th century artists of the Dada, Surrealist and Conceptual movements, his Three Eggs reflects on the question of what is real and what is image. Three Eggs is 1) a video camera projecting on an egg; 2) a tv screen showing the projected image of this egg, and 3) a tv monitor with the screen removed– replaced by an egg. There is irony and humor, but the passage of time is important to these 3 images, as well, having been made over 7 years. It reminds the student of Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs or Rene Magritte’s Treason of Images, 1929, works found in most art history textbooks.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Jul 23, 2011 | Exhibition Reviews, Expressionism, Franz Marc, Kandinsky, Modern Art, Paul Klee, The Phillips Collection

The Phillips’ Kandinsky exhibition centers around this painting from

the Guggenheim, Painting with White Border, 1913. It appears primarily

abstract, but has two specifically Russian iconographic references: a troika

(three horses) and St. George and the Dragon.

The Phillips Collection’s current exhibition on Kandinsky not only provides insight into the thought process of this giant of early 20th century abstraction, but it also gives us a chance to compare the artists with whom he worked and influenced.

The Phillips Collection’s current exhibition on Kandinsky not only provides insight into the thought process of this giant of early 20th century abstraction, but it also gives us a chance to compare the artists with whom he worked and influenced.

The Kandinsky exhibition is juxtaposed next to an exhibition of contemporary artist Frank Stella, whose sculptures are influenced by music of Domenico Scarlatti, called Stella Sounds. The metal and plastic sculptures point, poke off the walls and into space curving vigorously with color. They become 3-dimensional expressions of abstraction comparable to Kandinsky.

Frank Stella’s K43 comes out of the wall and into space. His sculptures

on view at the Phillips are based on the Sonatas of Italian composer Domenico Scarlatti

Both artists were inspired by music and Stella admits his appreciation for Kandinsky. Kandinsky named most of his early abstract paintings with titles suggestive of music: Improvisation, Composition, Impression, followed by a number. Ironically, the Phillips calls its exhibition Kandinsky and the Harmony of Silence: Painting with a Large White Border. The white border may be silent and restful, but the rest of this large painting has a rich depth, as each strong color pushes into space and clamors for attention.

The Phillips exhibition is educational, showing his drawings and his working process. Included is Sketch 1 for Painting with White Border (Moscow), a major holding of The Phillips Collection, as well as ten other preparatory studies in watercolor, ink, and pencil. But even more instructive is putting Kandinsky in perspective with his colleagues in two German art groups, the Blaue Reiter and the Bauhaus. If the great Russian painter and philosopher was the spiritual leader amongst the abstract artists centered around Munich, their spokesman, it is fitting because his art is the brashest and most assertive of the group.

The Phillips Collection has a superb painting by Franz Marc, Deer in the Forest, II. Looking forward to environmentalism, this painting hints at the destruction of nature in the 20th century. Unfortunately the artist himself died in World War I.

The Phillips owns many paintings done by Kandinsky’s colleagues : Franz Marc, the other leader of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) who died in World War I; the nervous Austrian, Oskar Kokoschka; the whimsical, childlike but sophisticated Paul Klee, and the playful American-German Lyonel Feininger. It’s a special treat to see the other early masters of Expressionism.

Lionel Feininger’s Village is a geometric construction of shifting planes of color.

Lionel Feininger’s Village is a geometric construction of shifting planes of color.

Beginning in 1922, Kandinsky taught at the Die Bauhaus, a comprehensive art and design school. Paul Klee was one of his colleagues there, as well as in Der Blaue Reiter. Klee’s art is as abstract, automatic and free as Kandinsky. But his vision is more subtle, more simple and more symbolic. Having at least 5 paintings by Klee to compare, we clearly see the difference.

Paul Klee,Tree Nursery, 1929, is one of several Klee paintings on view to compare with Kandinsky. In Klee’s paintings–not Kandinsky’s – we see the harmony of silence.

Paul Klee,Tree Nursery, 1929, is one of several Klee paintings on view to compare with Kandinsky. In Klee’s paintings–not Kandinsky’s – we see the harmony of silence.One of the great strengths of this Washington museum is its commitment to comparative exhibitions which give the viewer a fuller understanding of individual artists. Fortunately, the Phillips already has a large collection of early Modernism to supplement its exhibitions. The Kandinsky and Stella displays will be on view until September 4.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 8, 2011 | Caryatids, Erechtheion, Greek Art, Mythology, Sculpture, the Acropolis

Six famous women hold up the Porch of the Maidens of the Erechtheion, a temple on the Acropolis of Athens. These statues are admired for their graceful poses and drapery, but who notices the hair? An Art Historian who specializes in the sculpture of the Acropolis, Katherine Schwab, has studied the hairstyles and made a project of it for her students at Fairfield University in Connecticut. Here’s a summary of a presentation she gave last night at the Greek Embassy in Washington.

In the New Acropolis Mus eum, Athens –which was just built a few years ago — one can see the statues from the back with their beautiful long braids of hair, falling in fishtails followed by more curls. In fact, the hair of the statues is in better condition than the faces and bodies whose arms are completely missing. (Caryatid is the name given to a feminine statue which acts as a column to hold up a building; Kore is a statue of a maiden.)

eum, Athens –which was just built a few years ago — one can see the statues from the back with their beautiful long braids of hair, falling in fishtails followed by more curls. In fact, the hair of the statues is in better condition than the faces and bodies whose arms are completely missing. (Caryatid is the name given to a feminine statue which acts as a column to hold up a building; Kore is a statue of a maiden.)

These six caryatids are

labeled Kore A – Kore F.

Every hairstyle is a bit different. Most have fishtail braids down the back, along with regular braids wrapped around the head. Some of the caryatids have sidecurls, while others do not. Professor Schwab did the Caryatid Project with hai r stylist Miloxy Torres who recreated the braids on 6 students, all of whom had long, thick and mainly curly hair. The students acted out the caryatid poses other at the Fairfield University c

r stylist Miloxy Torres who recreated the braids on 6 students, all of whom had long, thick and mainly curly hair. The students acted out the caryatid poses other at the Fairfield University c ampus in 2009.

ampus in 2009.

The Porch of the Maidens adorns the Erechtheion which honors Athena, Poseidon, and two legendary kings Erechtheus and Krekops. It is an unusual building in many ways: three porches of different sizes going out in different directions. It was of special civic and religious significance to the ancient Athenians, because it marked the site of the contest between the god of the sea, Poseidon (Neptune) and Athena, goddess of war and wisdom, for control of Athens. In that competition presided over by legendary King Kekrops, Poseidon’s Neptune struck a hole on a rock to bring forth a spring of salt water. Nearby, in front of the building, Athena miraculously brought to life an olive tree. Athena’s gift was deemed greater and she became the ruler of Athens. One portion of the Erechtheion contains a wooden statue of Athena which fell from heaven during the reign of Erechtheus, but the Porch of the Maidens stands over the hole where Poseidon tapped his trident.

|

| The original caryatids are now on view in the New Acropolis Museum, Athens |

The photos are from the Caryatid

Project and Wikipedia. For more information and a video, see

www.fairfield.edu/caryatid Here’s the video

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 5, 2011 | 19th Century Art, Exhibition Reviews, Gauguin, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, National Gallery of Art Washington, The Art Institute of Chicago

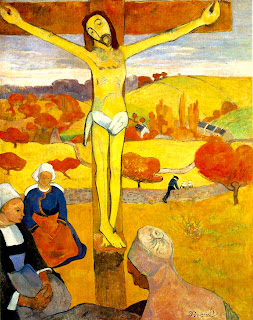

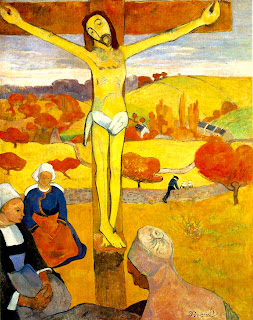

Paul Gauguin was impressed with the sincere, unspoiled piety of women from Brittany, where he painted in 1887. He placed the Yellow Christ, 1889, in a Breton landscape.

Paul Gauguin was impressed with the sincere, unspoiled piety of women from Brittany, where he painted in 1887. He placed the Yellow Christ, 1889, in a Breton landscape.

Paul Gauguin, an early modern rebel against western culture, is influenced by religious culture like his French forebears who painted for kings and churches 400 years earlier. After seeing the Art Institute of Chicago’s exhibition of

Early Renaissance Art in France, I saw the Gauguin exhibition at the National Gallery. Many of Gauguin’s subjects also had religious themes. He put the Crucifixion in a setting of yellow and ocher pigments, and blended it into the landscape of Brittany, a region he respected for its piety and cultural backwardness at that time.

The standing woman in Delectable Waters, above, has the shame of Eve being expelled from the garden of Paradise. We don’t know her relationship to the other women, although they also seem to live in a lush tropical place, much like a Garden of Eden

The standing woman in Delectable Waters, above, has the shame of Eve being expelled from the garden of Paradise. We don’t know her relationship to the other women, although they also seem to live in a lush tropical place, much like a Garden of Eden

Many of the paintings in Gauguin: Maker of Myth come from his Tahitian stay after 1891. He treats several scenes of Tahitian women and gods through the lens of Christianity and other religious traditions. It’s curious that the moon goddess Hina who appears in Delectable Waters, above, is actually in a pose from Hinduism that Gauguin morphs into this Tahitian image. In some canvases the Tahitian women, rather than Eve, deal with evil and temptation. He portrays human dramas of guilt, fear, agony and pain.

Why Are You Angry, from the Art Institute of Chicago, has always fascinated me. It also seems to have a mysterious theme of guilt or shame. This encounter between a standing lady and two seated girls who humble themselves creates a provocative drama separated by an old woman and a tree. Each woman is strongly modeled with lovely, brownish skin tones. The colors of this paradise blend warm hues of yellow and red with the cool, peaceful colors of mauve and blue.

Why Are You Angry, from the Art Institute of Chicago, exemplifies Gauguin’s ability to balance the warm and cool colors of nature, while the composition is balancing the various sides of the human drama .

Even before going to Tahiti, he painted of Christ’s

Agony in the Garden, showing Jesus is a human who feels the same pain of rejection that we, as humans, do. He uses his own face as Jesus Christ. Bright red-orange hair is symbolic of the fire and pain of human suffering, which we see not only as Jesus but part of humankind. There are many self-portraits on view

. Symbolist Self-Portrait from the National Gallery’s collection, shows the paradox of his own good and evil natures, making his choices appear like Adam and Eve’s. More powerful than ego promotion, these self-portraits are powerful expressions of the human dilemma. After all, he started out as a stockbroker, which clearly did not work for him. The exhibition has an impressive display of Gauguin’s sculpture and ceramics, even in self-portraiture.

The Agony in the Garden, is a Christian theme. Here Gauguin has given Jesus his own face, suggesting that he empathized and identified with the suffering of Jesus.

The Agony in the Garden, is a Christian theme. Here Gauguin has given Jesus his own face, suggesting that he empathized and identified with the suffering of Jesus.

One can wonder if Gauguin ever overcame his pain, shame and reached a type of salvation in his final destination, Tahiti. Whether it was Eden, Tahiti or Gethsemane, he seems to paint so many gardens, the paradises for which he hoped. (He had spent a childhood in Peru, traveled to the island of Martinique, to the opposite corners of France, Brittany and Arles, in search of simplicity before arriving in the South Seas.) Curiously, there are no paintings representing his short stay in Arles with Vincent Van Gogh.

In the end, Gauguin leaves his meanings ambiguous, but color is Gauguin’s salvation as an artist.

Two Women, above, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, shows Gauguin’s gift of color–not only yellow sky and brilliant red cherries. The woman to the right is painted with green hues beneath her brown skin, a wonderful match for her blue dress, while the other women has red under brown skin.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 5, 2011 | Christianity and the Church, Renaissance Art, The Art Institute of Chicago

This Crucifixion from the Getty Museum is the center of a 3-part altarpiece which can be seen at the Art Institute in its original format until May 30th. The unknown master used saturated colors in oil paint, while packing an incredible amount of detail into a panel 19 x 28 inches. Click on the photo to see an enlargement.

This Crucifixion from the Getty Museum is the center of a 3-part altarpiece which can be seen at the Art Institute in its original format until May 30th. The unknown master used saturated colors in oil paint, while packing an incredible amount of detail into a panel 19 x 28 inches. Click on the photo to see an enlargement.The Art Institute of Chicago is currently showing a major exhibition of French Renaissance painting, Kings, Queens and Courtiers. To me, the most impressive and interesting piece is by an unknown painter, the Master of Dreux Budé. It dates to about 1450.

One of the values of this type of scholarly exhibition is the opportunity to find and gather lost or separated parts of paintings. Here, we view the original pieces of what was once formed a triptych, three panels connected by hinges to tell a concise history of Christian Salvation. The largest painting was in center; it’s a Crucifixion from the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The Resurrection, from the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, France, was once a wing on the right side.

It’s a special treat to see the left panel, The Kiss of Judas or Betrayal of Christ, which starts this Passion, Death and Resurrection story. (The painting is in private hands, therefore rarely seen and photographed.) This artist’s conception is very original; Judas’ kiss of betrayal is set in the darkness of night with moon, stars and faces as the light which heightens the drama of Christ’s arrest. Suddenly we notice a crowd of soldiers that is emerging from behind. The Crucifixion in center continues the story in a daytime landscape and tells multiple episodes as well, including the Harrowing of Hell on the far right.

Each panel o f the painting is a masterpiece by itself but more complete when grouped together. The unknown painter is a vivid and imaginative storyteller.

f the painting is a masterpiece by itself but more complete when grouped together. The unknown painter is a vivid and imaginative storyteller.

A few suggestions for the identity of this painter have been made: Andre d’Ypres or Colin d’Amiens. We know of the patrons: Dreux Budé, a wine merchant, and his wife, Jeanne Peschard. The three-part painting, called a triptych, was for the altar in the Budé family chapel of Saint Gervais, Paris. A Crucifixion in the Louvre, Paris, is by the same painter, who  may have learned from Rogier and/or Robert Campin in the guild of Tournai.

may have learned from Rogier and/or Robert Campin in the guild of Tournai.

A double-mouth demon and sinners in a cauldron, above left. In the bottom left of the Crucifixion is a demon in Hell whom Jesus encountered while going there to rescue Adam and Eve. The photo is courtesy of Dawn Pedersen of Blue Lobster Art & Design.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Electronic Superhighway, 1995,a gift from the artist to the Smithsonian American Art

Electronic Superhighway, 1995,a gift from the artist to the Smithsonian American Art One Candle, Candle Projection, 1988-2000 candle, candle monitoring device, closed circuit camera, projectors, distribution amplifier, and 5″ color monitor, dimensions variable Nam June Paik Estate

One Candle, Candle Projection, 1988-2000 candle, candle monitoring device, closed circuit camera, projectors, distribution amplifier, and 5″ color monitor, dimensions variable Nam June Paik Estate

Recent Comments