by Julie Schauer | Apr 8, 2016 | 18th Century Art, Elizabeth Vigée-LeBrun, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Portraiture, Women Artists

|

| Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, Self-Portrait with Cerise Ribbons, c. 1782, Kimbell Art Museum |

Vigée-Le Brun: Woman Artist of Revolutionary France is major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum until May 15. Élisabeth Louise Vigée-Le Brun’s Self-Portrait from the Kimbell Art Museum explains her quite well. She shines with the confidence and elegance of a woman who would eventually become an international superstar. It shows off her top-notch artistic skills. Touches of brilliant red for the ribbon, sash, lips and cheeks to add sensual pizzaz. Portraits are not my favorite genre of painting, but Vigée-Le Brun’s portraits are always dazzling. The light radiating through her earring is just the right touch. One reason we never hear her mentioned among France’s top ten or twenty painters is that she was a painter of royalty who supported the wrong side of the French Revolution. It is only last year that France gave her a major retrospective, although her international reputation was strong back in her day.

|

Jacques-Francois Le Sevre, c. 1774

Private Collection |

Vigée-Le Brun compares well with Jacques-Louis David and the very best French artists of her time. For the most part, she was fairly traditional rather than an innovator. Her style has elements of the late Rococo and Neoclassical styles, but with the addition of some naturalistic features. She was largely self taught, having learned from her painter father before he died when she was 12. Her mother was a hairdresser. She set up her own studio at age 15, supporting herself, mother and younger brother. After her mother remarried, she painted her stepfather, Monsieur Le Sevre (whom she really didn’t like, though I can’t discern it in the painting.) She was only about 19 at the time she painted it, around the same time she entered the Academy of Saint Luke, the painter’s guild.

Vigée-LeBrun was earning enough money from her portrait painting to support herself, her widowed mother, and her younger brother. T – See more at: http://www.nmwa.org/explore/artist-profiles/%C3%A9lisabeth-louise-vig%C3%A9e-lebrun#sthash.AhJDfSMB.dpufsupporting herself, her mother and younger brother. After her mother remarried, she painted her stepfather. The portrait of Monsieur LeSevre, is superb, though the artist was probably no older than 19. Around the same time, she joined the Academy of St. Luke (the painter’s guild). She soon made her way to the top. A few years later, she was called to work at Versailles, becoming the personal painter of Marie Antoinette. She commanded some very high prices for her work.

|

| Joseph Vernet, 1778, Louvre Museum, Paris |

In 1778, she painted Joseph Vernet, a distinguished older painter of seascapes whom she greatly admired. He counseled her to always look at nature. I had seen the Vernet portrait in a NMWA exhibition a few years ago, a monumental exhibition that brought to light many of the gifted female artists of the era. the Met describes Vernet as her mentor, and it’s easy see the affectionate expression in this portrait. It has a wonderful harmony of various blacks and grays.

Painters are sometimes divided into those who are great draftsmen (like Michelangelo and Ingres) or great colorists (like Titian and Rubens). Vigée-Le Brun combines drawing ability and an exquisite sense of color. (There are several drawings in the exhibition.) Vigée-Le Brun’s father, Louis Vigée was a pastel artist and the self-portrait she did in pastel is just lovely. It combines loose, free lines with delicate, subtle modeling to make the face pop out. What other artists can make black, white and gray so interesting?

|

Self-portrait in Traveling Costume

1789-90, pastel, Private Collection |

Marriage, Her Husband and Daughter

In 1776, she married Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun, a painter, art dealer and a great connoisseur who fostered an appreciation of northern artists. He was the grandnephew of Charles Le Brun, founder of the French Academy. Together they traveled to Flanders and the Netherlands to study the northern artists. She was a greater painter than he was, but it was a connection of great mutual benefit for both of them. In 1780, a daughter, Jeanne Julie, was born. Julie became the subject of many of her mom’s paintings. A real gem of the show is the portrait of her daughter looking in a mirror. It simultaneously gives us a frontal and profile view. It is also a very sentimental painting.

|

Julie LeBrun Looking in a Mirror

c. 1786, Private Collection |

One self-portrait by her husband is in the exhibition. He was probably the most important art connoisseur and dealer in France in his time. Pierre Le Brun is credited with writing the most important book on Netherlandish art and elevating the reputation of one of the world’s most popular Old Masters, Johannes Vermeer.

In 1783, Vigee-Le Brun gained entry into the prestigious Royal Academy, one of only four women in the elite group. There was some conflict of interest, because her husband’s profession as an art dealer could have disqualified her. However, King Louis XVI used his influence to promote her. Even at the relatively young age of 28, she commanded higher prices than her peers.

At the time, history painting, meant to instruct and moralize, was considered the highest category of painting. The canvas she submitted for admission into the French Academy was an allegorical piece meant to inspire virtue, Peace Bringing Back Abundance. As the name suggests, prosperity comes from staying out of war. While the classical Grecian style of this painting is not the taste of today, it’s her colors that I love. Unfortunately, peace would not remain in her life and in France for very long.

|

| Peace Bringing Back Abundance, 1780, Louvre Museum, Paris |

When Marie-Antoinette fell from favor and lost her life, Vigée-Le Brun had reason to be afraid. She left France for Italy, with her daughter and without her husband. She was quickly accepted into the Accademia di San Lucca in Florence. She was asked to add her portrait to the the Corridoio Vasariano at the the Uffizi, an obvious sign that her reputation preceded her. This self-portrait in the Uffizi Gallery, painted in 1790, is one of her most famous paintings (below). According to the Metropolitan Museum, the ruffled collar was meant to show her affinity to Rubens and Van Dyke. The cap is reminiscent of self-portraits by Rembrandt, but the brilliant red sash and the use of color contrast is strictly Elisabeth Vigee – Le Brun. It shows greater spontaneity than some of her royal commissions. A few years earlier she had been criticized for breaking with convention by painting self-portraits with an open mouth, making them look less serious.

|

| Self-portrait, 1790, Uffizzi Gallery, Florence |

With her out of the country and the Reign of Terror going on in France, her husband was forced to divorce her. (When the aristocracy lost power, he also lost his major clients.) She remained in exile for 12 years, but painted in the Austrian Empire, Russia and Germany. Her services as a painter were in high demand and she commanded high prices from her lofty, aristocratic clients. In particular, she painted many Russian aristocrats, including one owned by the National Museum for Women in the Arts which is not in the current exhibition.

Portraits of Russian and Foreign Aristocrats

|

Duchess Elizabeth Alexyevna, 1797

Hessische Hausstiftung, Kronberg |

Many of the paintings on view at the Met are from private collections, suggesting that many portraits may still be owned by descendants. None of her paintings from Russian museums are on loan to the United States, because of diplomatic problems at this time. The exhibition going to National Gallery of Canada in June will have several paintings from the Hermitage that are not in the New York show. These paintings were included in the Paris, where the exhibition started.

Vigée Le Brun painted at least five portraits of Grand Duchess Elizabeth Alexyevna, but the example here has a sumptuous red cushion and a transparent purple shawl, that sets off nicely against white skin, dress and long flowing hair.

|

Duchess von und zu Liechtenstein as Iris

1793, Private Collection |

Vigée Le Brun also enjoyed depicting personifications and allegory, as did many of the artists of this era. At one time she painted her daughter as the goddess of flowers, Flora. When she painted the beautiful Duchess von und zu Liechtenstein, she imagined her as Iris, the goddess of the rainbow. The colors shine brightly, though a rainbow which I expected to discern in real life, at the exhibition can’t be found in the painting.

In general, she greatly flattered her sisters. It would seem that she only painted women who were beautiful. At the Metropolitan show, about 5/6 of the paintings portray female sitters. She carefully considered all props, and how to reflect the personality of the sitter. Vigée Le Brun figured out how to bring out their best features and reflect the personality of the sitter.

|

| Countess Anna Ivanova Tolstaya, 1796, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa |

The use of materials, props and settings is crucial to her goals. A portrait of Countess Anna Ivanova Tolstaya has a large outdoor background taken from the natural world, a Romantic setting. The countess looks dreamy and wistful. In general, there is a very wide variety to the types of colors she used, and the harmonies she created. The National Museum of Women in the Arts currently has an exhibition on Salon Style, which includes portraits by Vigee Le Brun, among other French women artists. An unattributed pastel of Marie Antoinette would appear to be by Vigee-Le Brun, too, or at least copied from a painting by her.

Vigée-Le Brun’s Legacy and Queen Marie-Antoinette

From a strictly historical perspective, however, her connections to the French Royal family may be the most important contribution. From her many portraits of Marie-Antoinette, historians can look for clues into the life and character of this demonized queen. It’s difficult to figure out if Marie-Antoinette was really as bad a person as history portrays her. I saw the Kirsten Dunst movie about her and more recently a play about her, both of which show her as a tragic figure who was a foreigner and really didn’t really know how to fit into the world into which she married. We may never really know. Marie-Antoinette may have wanted Vigée Le Brun to soften her image. Several portraits of her are in the exhibition. The bouffant, powdered hairdos don’t beautify her to me. Marie-Antoinette and Her Children, a large, flamboyant group portrait loaned shows the young queen with three children and an empty cradle. It emphasizes that the Austrian-born queen had recently lost a child. So even in this sumptuous setting there is great sadness and loss.

|

Marie-Antoinette and Her Children, 1787, Musée National des

Chateaux de Versailles et de Trianon |

Madame Royale and the Dauphin Seated is a portrait of the two oldest children when the were around 3 and 6 years old. The princess’ satin dress is brilliant display of Vigee Le Brun’s skill at portraying texture. The pastoral background is nostalgic and adds to the sense of innocence. It gives no hint of what’s to come. The prince died of tuberculosis in 1789, ate age 7. (Dauphin County, Pennsylvania is named after him.) Marie-Therese, named for her grandmother, was imprisoned between 1789 until 1795. She was queen 20 days in 1830 and lived until 1851, but generally had a very sad life. There is actually one landscape painting in the exhibition (and there were several landscape drawings in the Paris exhibition), but Vigee Le Brun is first and foremost a portrait painter.

|

Madame Royale and the Dauphine Seated, 1784, Musee National

des Chateaux de Versailles et de Trianon |

|

Between 1835 and 1837, Vigée Le Brun wrote her memoirs. A remarkably great artist and a remarkable woman, she lived to be 86. She is appreciated much more than for her paintings of many Marie – Antoinette. When I took a college Art History class that started with the French Revolution and went to about 1850, we didn’t cover Vigée-Le Brun. David, the academic teacher who influenced so many students, was treated like a god in my class. I find it curious that Vigée-Le Brun remained completely loyal to the royal family, while David was such a politician. He painted for the king, turned into a revolutionary and then easily switched gears to become Napoleon’s artist. He secured his reputation for posterity. With this exhibition traveling to Paris, New York and Ottawa, Vigée-Le Brun’s reputations will go up a few notches, putting her in a rank equal rank to that of David. The Metropolitan has a complete list of paintings in the exhibition. See the Met’s video of her.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 16, 2016 | Art and Science, Greater Reston Arts Center, Ramon Cajol, Rebecca Kamen, Steven J. Fowler, Susan Alexjander, theory of relativity

|

| Rebecca Kamen, NeuroCantos, an installation at Greater Reston Arts Center |

Six years ago, The Elemental Garden, an exhibition at Greater Reston Arts Center (GRACE) prompted me to start blogging about art. Like TED talks, the news of something so visually fascinating and mentally stimulating as Rebecca Kamen’s integration of art with sciences needs to spread. GRACE presented her work in 2009 and did a followup exhibition, Continuum, which closed February 13, 2016.

|

| Rebecca Kamen, Lobe, Digital print of silkscreen, 15″ x 22″ |

Like the Elemental Garden, Kamen’s new works visually evoke and replicate scientific principles. For the non-scientist and the scientist, the works and their presentation are fascinating. Kamen worked with a British poet and a composer/musician from Portland, Oregon, each with similar intellectual interests.

Two prints included in the show create a dialogue between her design and the words of poet Steven Fowler. I like how the idea of gray matter is overlapped by darker conduits, in Lobe, above. There’s a wonderful sense of density and depth.

While her last exhibition at GRACE was mainly about the Periodic table in chemistry, this time Rebecca Kamen’s exhibition included additional themes such as neural connectivity, gravitational pull, black holes and other mysteries of the universe. Why use art to talk about science? In a statement for Continuum, Kamen starts with a quote by Einstein: “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science.”

Both art and science are creative endeavors that start with questions. One time Kamen told me that she knows there is some connection between the design of the human brain and the design of the solar system, that has not yet been explained. NeuroCantos, the installation shown in the photo on top, explores this relationship. Floating, hanging cone-like structures made of mylar represent the neuronal networks in the brain, while circular shapes below symbolize the similarity of pattern between the brain and outer space, the micro and macro scales. It investigates “how the brain creates a conduit between inner and outer space through its ability to perceive similar patterns of complexity,” Kamen explained in an interview for SciArt in America, December 2015. The installation brings together neuroscience and astrophysics, but it’s initial spark came from a dialogue with poet Fowler. (They met as fellows at the Salzburg Global Seminar last February and participated in a 5-day seminar exploring The Art of Neuroscience.)

|

| Rebecca Kamen, Portals, 2014, Mylar and fossils |

Nearby another installation, Portals, also features suspended cones hanging over orbital patterns on the floor. The installation interprets the tracery patterns of the orbits of black holes, and it celebrates the 100th anniversary of Einstein’s discovery of general relativity. It’s inspired by gravitational wave physics. To me, it’s just beautiful. I can’t pretend to really understand the rest. The entire exhibit is collaborative in nature, with Susan Alexjander, composer, recreating sounds originating from outer space. The combination of sound, slow movement and suspension is mesmerizing.

Terry Lowenthal made a video projection of “Moving Poems” excerpts from Steven Fowler’s poems and a quote from Santiago Ramon y Cajal, artist and neuroscientist.

There are also earlier works by Kamen, mainly steel and wire sculptures. With names like Synapse, Wave Ride: For Albert and Doppler Effect, they obviously mimic scientific effects as she interprets them. Doppler Effect, 2005, appears to replicate sound waves drawing contrast in how they are experienced from near or far away.

|

| Rebecca Kamen, Doppler Effect, 2005, steel and copper wire |

Kamen is Professor Emeritus at Northern Virginia Community College. She has been an artist-in-residence at the National Institutes of Health. She did research Harvard’s Center for Astrophysics and at the Cajal Institute in Madrid. Her art has been featured throughout the country; while her thoughts and concepts have been shared around the world.

For more information, check out www.rebeccakamen.com, www.oursounduniverse.com (Susan Alexjander) and www.stevenjfowler.com

The Elemental Garden

|

| Elemental Garden, 2011, mylar, fiberglass rods |

To the left is a version of The Elemental Garden in Continuum. An identical version is in the educational program of the Taubman Museum of Art, Roanoke, VA.

(The following is how I described it while writing the original blog back in 2010) Sculptor Rebecca Kamen has taken the elemental table to create a wondrous work of art. The beautiful floating universe of Divining Nature: The Elemental Garden–recently shown at Greater Reston Area Arts Center (GRACE)–is based on the formulas of 83 elements in chemistry. Its amazing that an artist can transform factual information into visual poetry with a lightweight, swirling rhythm of white flowers.

According to Kamen, she had the inspiration upon returning home from Chile. After 2 years of research, study and contemplation, she built 3-dimensional flowers based upon the orbital patterns of each atom of all 83 elements in nature, using Mylar to form the petals and thin fiberglass rods to hold each flower together. The 83 flowers vary in size, with the simplest elements being smallest and the most complex appearing larger. The infinite variety of shapes is like the varieties possible in snowflakes; the uniform white mylar material connects them, but individually they are quite different.

|

| Rebecca Kamen, The Elemental Garden, 2009, as installed in GRACE in 2009 (from artist’s website) |

One could walk in the garden and feel a mystical sensation in the arrangement of flowers, as intriguing as the “floral arrangement” of each single element. After awhile I discovered that the atomic flowers were installed in a pattern based upon the spiral pattern of Fibonacci’s sequence. Medieval writer Leonardo Fibonacci and ancient Indian mathematicians had discovered the divine proportion present in nature. This mystical phenomenon explains the spirals we see in nature: the bottom of a pine cone, the spirals of shells and the interior of sunflowers among other things. Greeks also created this pattern in the “golden section” which defines the measured harmony of their architecture. Kamen wanted to replicate this beauty found in nature

Kamen likened her flowers to the pagodas she had seen in Burma. However, there is an even more interesting, interdisciplinary connection. Research on the Internet brought Kamen to a musician, Susan Alexjander of Portland, OR, who composes music derived from Larmor Frequencies (radio waves)emitted from the nuclei of atoms and translated into tone. Alexjander collaborated, also, and her sound sequences were included with the installation. Putting music and art together with science mirrors the universe and it is pure pleasure to experience this mystery of creation.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 13, 2016 | Ceramics, Contemporary Art, Eva Zeisel, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Industrial Design, Isamu Noguchi, Karen Karnes, National Museum for Women in the Arts, Ruth Asawa, Surrealism

|

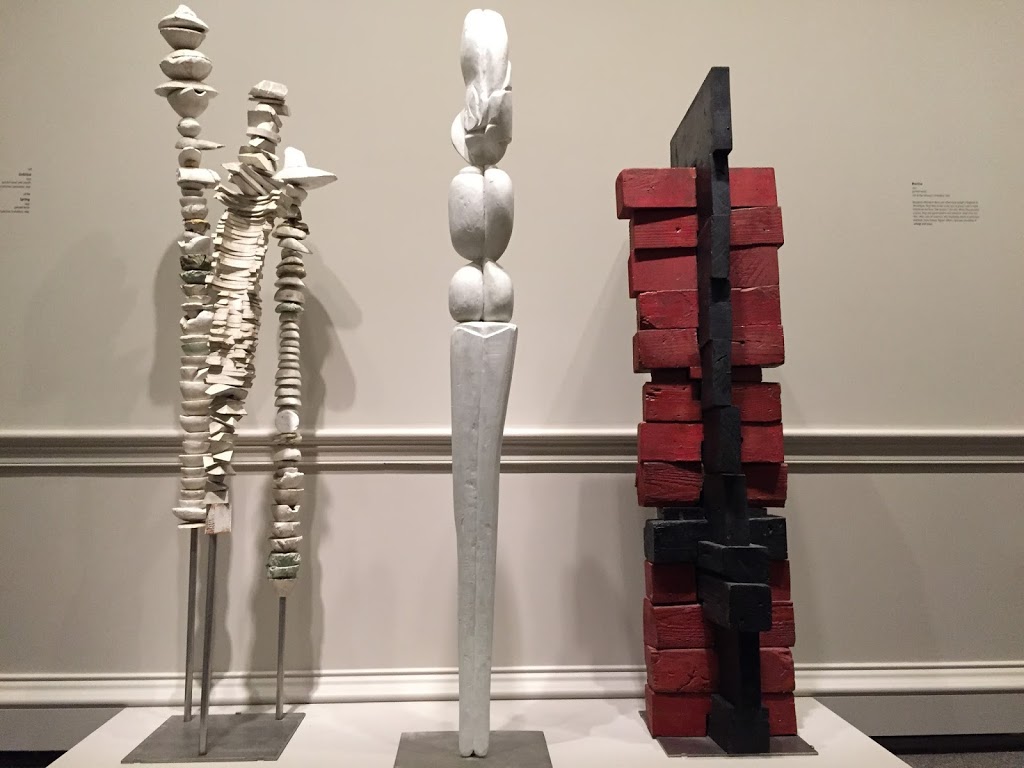

Isamu Noguchi, Trinity, 1945, Gregory, 1948, Strange Bird (To the Sunflower)

Photo taken from the Hirshhorn’s Facebook page |

Biomorphic and anthropomorphic themes run through quite a few exhibitions of modern artists in Washington at the moment. The Hirshhorn’s Marvelous Objects: Surrealist Sculpture from Paris to New York has several of the abstract, biomorphic Surrealists such as Miro and Calder. The wonderful exhibition will come to a close after this weekend.

Isamu Noguchi’s many sculptures that are part of Marvelous Objects deal with an unexpected part of the artist’s life and work. Noguchi was interned in a prison camp in Arizona for Japanese-Americans during World War II. Whatever the horrors of his experience, he dealt with it as an artist does — making art and using creativity to express the experience by transforming it.

|

| Isamu Noguchi, Lunar Landscape, 1944 |

Lunar landscape comes from immediately after this difficult time period. The artist explained, “The memory of Arizona was like that of the moon… a moonscape of the mind…Not given the actual space of freedom, one makes its equivalent — an illusion within the confines of a room or a box — where imagination may roam, to the further limits of possibility and to the moon and beyond.” It’s like taking tragedy and turning it into magic.

|

| Strange Bird (To the Sunflower), 1945 Noguchi Museum, NY |

|

|

The most interesting piece from this period is Strange Bird (To the Sunflower), 1945. It is pictured here 2x — on top photo, right side, and from a different angle on the left, from a photo in the Noguchi Museum. Between 1945 and 1948, Noguchi made a series of fantastic hybrid creatures that he called memories of humanity “transfigurative archetypes and magical distillations.” Yet the simplicity and the Zen quality I expect to see in his work is gone from this time of his life.

From the beginning of time, “humans have wanted a unifying vision by which to see the chaos of our world. Artists fulfill this role,” said Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto.

I’m reminded of the ancient Greeks who created satyrs and centaurs to deal with their animal nature. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there’s a small Greek sculpture of a man and centaur from about 750 BCE, the Geometric period. The man confronting the centaur seems to be taming him or subduing his own animal nature. Like Noguchi’s sculpture, it has hybrid forms and angularity, but it’s made of bronze. Noguchi’s sculpture is of smooth green slate, which gives it much of its beauty and polish.

|

| Man and Centaur, bronze, 4-3/4″ mid-8th century BCE Metropolitan Museum |

Noguchi was a landscape architect as well as a sculptor. When designing gardens, he rarely used sculpture other than his own. Yet he bought garden seats by ceramicist Karen Karnes. A pair of these benches by Karnes are now on display at the National Museum for Women in the Arts’ exhibition of design visionaries. Looking closely, one sees how she used flattened, hand-rolled coils of clay to build her chairs. The craftsmanship is superb. It’s easy to see how her aesthetic fit into Noguchi’s refined vision of nature.

|

| Karen Karnes, Garden seats, ceramic, from the Museum of Arts in Design, now at NMWA |

|

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 10, 2016 | 20th Century Art, Constantin Brancusi, Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi, Louise Bourgeois, Sculpture, Surrealism

“Contemporary and ancient art are like oil and water, seemingly opposite poles….now I have found the two melding ineffably into one, more like water and air.” Hiroshi Sugimoto, Japanese artist

|

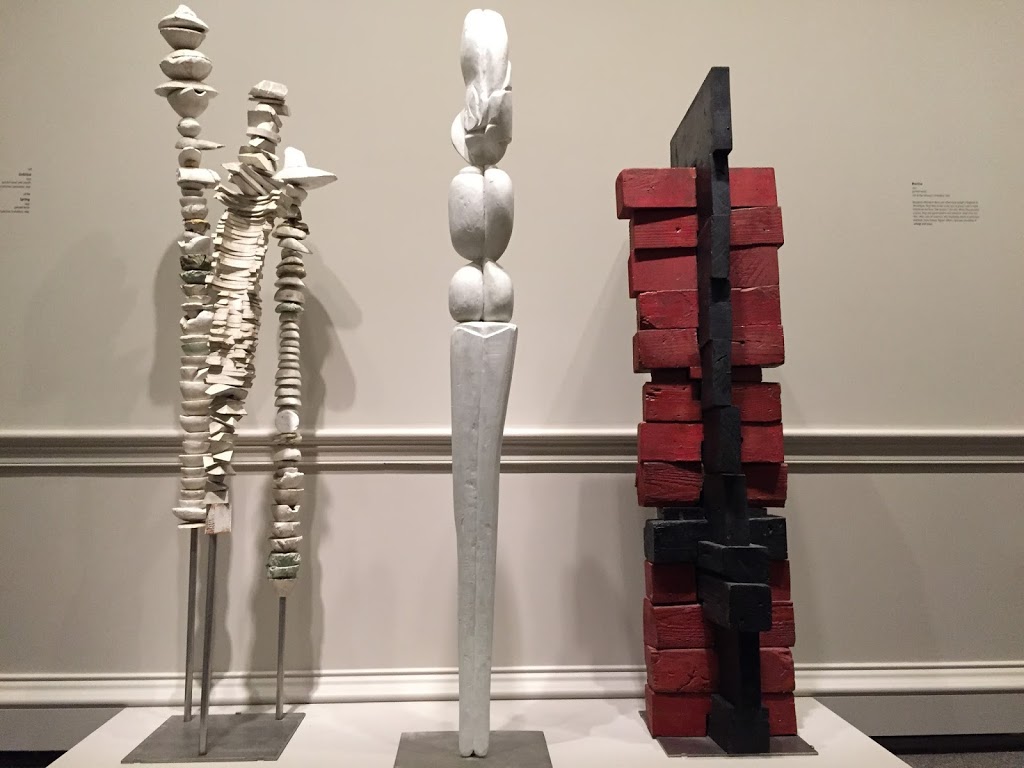

| Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1952, Spring, 1949 and Mortise, 1950 National Gallery of Art |

|

|

Two separate exhibitions in Washington at the moment illustrate the commonality of modern art and prehistoric — especially in sculpture. The me, that theme resonates with two sculptors who lived through most of the 20th century, Louise bourgeois and Isamu Noguchi. The National Gallery has a two-room exhibition Louise Bourgeois:No Exit, and Noguchi (hopefully in another blog)‘s works are part of the Hirshhorn’s exhibition, Marvelous Objects: Surrealist Sculpture from Paris to New York.

|

Constantin Brancusi, Endless Column,1937

|

|

|

Three sculptures by Bourgeois in the National Gallery are what she called personages. As a whole they’re not unlike the archetypal images of Henry Moore or Constantin Brancusi. Among these three works are a group of three piles of stones resting on stilts. It’s one of the Bourgeois sculptures that

|

Barbara Hepworth, Figure in Landscape,cast 1965

|

appears simple and somewhat primitive. Untitled is above on the left. The stones stand tall and top heavy; they seem to be wearing big hats. I’m reminded of the precarious state of human existence. I am also thinking of the top-heavy candidates in the recent Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary, weak on bottom and they may fall. Aesthetically these works form a link to Brancusi’s birds on pedestals and the Endless Column, Targu Jui, Romania, part of a memorial for fallen soldiers in World War I.

The sculpture of Spring center above is reminiscent of a woman, or of the ancient Venus figures, which date to the Paleolithic era, around 20,000 BCE. It can be compared the the elongated marble burial figures from prehistoric, Cycladic Greece as well.

|

| “Venus” figures from Dolni Vestinici, Willendorf, Austria and Lespuge, France |

|

|

|

A version of Alberto Giacometti’s bronze Spoon Woman from the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas is in the surrealist exhibition (Example below from Art Institute of Chicago). Giacometti made this archetypal image in 1926/27, but the bronze was cast in 1954. Henry Moore’s Interior and Exterior Forms, is a theme he did over and over, is an archetype of the mother and child.

|

| Giacometti, Spoon Woman, 1926/27, cast |

1954 |

In 1967, the Museum Ludwig, founded by chocolate manufacturers in Cologne, Germany, asked for one of her sculptures to be replicated in a single large piece of chocolate. She chose Germinal, its name suggestive of germination and new beginnings. (Germinal is also the name of Emile Zola’s famous French novel of 19th century coal minors. I wouldn’t put it past her to be referring to the story, but don’t have an idea as to how and why)

|

| Germinal, 1967, promised gift of Dian Woodner, copyright |

|

|

Bourgeois, who died in 2010, lived to be 98 years. She continually worked and invented anew. In time, I think she will be considered a giant among the sculptors of the 20th century, on par with Moore, Brancusi and Calder. Her art was more varied than the others and she defied categorization and/or predictability. However, certain themes seemed to carry her for long periods of time, such as the personages of her early to middle period and the cells she did late in her life. She worked both vary large and very small and with an infinite variety of materials including fiber. She grew up in a family which worked in the tapestry business, primarily repairing antique tapestries. To her, making art was making reparations making peace with the past. Some wish to put her in the category of Surrealism, but she calls herself an Existentialist, in the philosophical realm of Jean-Paul Sartre. Looking at some of the drawings in the National Gallery and how she explained it does give a clue into the existential thoughts and feelings.

|

| Spider, 2003 (not in exhibition) |

One of Bourgeois’s best-known themes was the spider, having done several monumental statues in public places. The spider stands for the protective mother, and her version of the archetype, as it also alludes to the weaving activity in her family. It is large and embracing but can also have a dark side. I like best the spiders that combine the metal sculpture with the delicate tapestry figures. The delicacy and litheness of her spider people remind me of the wonderful organic acrobat sculptures from ancient Crete.

|

| Bull-leaping acrobat, ivory, from Palace at Knossos, Crete, c. 1500 BCE |

Bourgeois deals with metaphors. She calls sculpture the architecture of memory. She is poetic, but she’s also quite humorous. She also made a sculpture series of giant eyes. She describes eyes mirrors reflecting various realities. I’m reminded that in ancient times, the eyes were the mirrors of a person’s soul. As different as her works may be, she portrays a consistent voice and aesthetic throughout her career.

|

| Eye Bench, 1996-97, Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle |

When I went to the Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle back in 2010, a friend of mine from California and I came upon her Eye Benches. We sat down and enjoyed it. She designed three different sets of eye benches made of granite. In the end, it seems Bourgeois used her art to make sense of her very complicated world and our experience of that world. Sometimes she seems to laugh at it all, so this experience calls for a good laugh and relaxation.

|

| Louise Bourgeois, Eye Bench, Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle. |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Dec 13, 2015 | Gauguin, Picasso, Rouault

|

Paul Gauguin, NAFAE faaipoipo (When Will You Marry?) 1892

Rudolph Staechelin Collection |

The Phillips Collection’s latest loan exhibition, “Gauguin to Picasso: Masterworks from Switzerland,” draws upon a pair of collections assembled by two prominent but very different Swiss art collectors. To me, the theme of dualism, pairs and split identities stands out strongly. The exhibition highlights one of Gauguin’s most famous paintings, When are You to be Married? — a painting that recently was sold. (The Staechelin and Im Oberstag collections of modern art are normally on display at the Basel Kunstmuseum. Here’s an article for background on the collectors why the paintings are traveling.)

Like so many other paintings by Gauguin, the two women in this infamous painting express two realities, which could represent the split identities within Tahitian society. He painted it during his first stay in Tahiti in 1892. The woman in front is natural, organic, relaxed and colorful in her red skirt. The orchid in her hair was said to suggest that she is looking for a mate. A woman behind is taller, more severe and covered in a pink dress buttoned to the top–an influence of Western missionaries. The woman in back has a bigger head than the woman in front. Does he mean to imply that she dominates? Or, is Gauguin imagining a single Tahitian woman who is torn between her native identity and the invasion of western civilization.

|

| Eugene Delacroix, Women of Algiers, 1834, The Louvre |

The woman in front may be inspired by one of the very beautiful, sensual women painted in Delacroix’s Women of Algiers, one of my all-time favorite paintings. (Delacroix was allowed into the mayor’s harem to sketch the women–pictured at right. Like Gauguin, Delacroix was European observing women in an exotic, foreign land.)

|

| Gauguin, Self-Portrait, 1889, NGA |

|

|

|

|

In his self-portraits and so much of his art, Gauguin expresses the split nature in mankind, the areas where there is inner conflict. Symbolist Self-Portrait at the National Gallery of Art (NGA), Washington, is a divided person, both a saint and a sinner. He has a choice in the matter, and we wonder what he’ll choose.

The two Tahitian women are different, yet blended. Warm brown skin tones unite them and the hot red skirt of the “natural” native woman flawlessly flows into the warm pink of the stiffer, “civilized” woman. The colors blend and contrast simultaneously into a beautiful harmony. (Is it surprising that this picture was the most expensive painting ever sold? Rumor has it that it was purchased by a Qatari for Qatar Museums.)

|

| Georges Rouault, Landscape with Red Sail, 1939, Im Obersteg Foundation, permanent loan to the Kunstmuseum Basel. Photo © Mark Gisler, Müllheim. Image © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris |

Other artists in this exhibition continue the theme of duality and split personality. Early 20th century Expressionist Georges Rouault was honest about his identity as a person belonging in another century, the age of the cathedrals. His heavily-outlined Landscape with Red Sail uses colors reminiscent of the colors in stained glass and the way stained glass is divided by lines of lead. Yet, his paint is applied in a very rough, heavy manner, hardly like the smoothness of glass. His beautiful seascape does, however, evoke the light of a sunset peaking behind the sailboat–like the light filtering in medieval churches.

|

| Alexej Jawlensky, Self-Portrait, 1911 Im Obersteg Collection |

|

|

The Expressionist painter Alexej von Jawlensky was a Russian living in Switzerland, in exile there during World War I. There’s a haunting quality to his Self-Portrait, left. Jawlensky and Im Obersteg had a strong friendship throughout his career.

One side of a Picasso painting features a woman in a Post-Impressionist style, “Woman At the Theatre,” and the other side has a sad woman, The Absinthe Drinker, from the beginning of the “Blue period.” Both were painted in 1901. They could not be more different from each other. Picasso was very experimental at that

|

| Picasso, The Absinthe Drinker, 1901 Im Obersteg Collection |

|

|

time of his life and in his career.

Expressionism is a large part of the exhibition, especially with Wassily Kandinsky, Chaim Soutine, Marc Chagall and Alexej von Jawlinsky. Swiss Symbolist Ferdinand Hodler shares with us his experience of love and death in a group of paintings of his dying lover Valentine Gode-Darel. It is difficult to watch and for him painting may have been an attempt to make peace with the awful situation.

The series of paintings by Hodler are some of the most powerful in the exhibition because we experience the unfolding of a tragedy. Gode-Darel died of cancer in

|

| Ferdinand Hodler, The Patient, painted 1914, dated 1915. The Rudolf Staechelin Collection © Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler |

1915, a year after diagnosis. The three paintings of rabbis by Marc Chagall continue in the theme of portraiture.

There are very fine small paintings by Cezanne, Monet, Manet, Renoir and Pissaro, two beautiful landscapes by Maurice de Vlaminck. Van Gogh’s, The Garden of Daubigny, 1890 is one of three he did of the same subject weeks before his death. The black cat in the painting is small but curiously out of place. The 60 paintings on view, on view until January 10 — are worth the trip to the Phillips. Here are some of the best photographs of the paintings in the show. These Swiss collections complement the Phillips own marvelous collection of early Modernism. It is curious that the Swiss collections don’t show the greatest of all 20th century Swiss artists, Paul Klee.

|

| Vincent Van Gogh. The Garden of Daubigny, 1890 Rudolf Staechelin Collection |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

Recent Comments