by Julie Schauer | Jan 23, 2017 | 19th Century Art, Manet, Victorine Meurent

|

| Detail of “Olympia” by Edouard Manet, 1863, in Musée d’Orsay |

Victorine Meurent is Manet’s most frequent model of his early career. She shocked audiences as the indifferent courtesan in Olympia (above), exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1864. A year earlier, Victorine had scandalized Parisians, playing the part of a shameless woman who disrobed during a midday picnic. That was her role in Manet’s revolutionary painting, Le déjeuner sur l‘herbe(The Luncheon on the Grass– see on bottom) exhibited at the Salon des Refusées for the officially rejected paintings of that year. She is just the matter-of-fact figure that Manet wanted, and there is nothing beautiful, sexual or erotic in either image. In both paintings, she is not an individual but the object, the sexual object.

Manet also painted Victorine as Young Lady (also called Woman with a Parrot), in 1866. She looks taller in her long pink gown. There’s a magnificent unpeeled lemon on the ground. The symbols in the painting may allude to the five senses and suggest that she is a mistress. But she is a sympathetic one, one who even seems satisfied with her status as a mistress. However, it’s hard to see each of these paintings as representative of the same woman. One supposes that Victorine refused to model naked again, after all the attention of Olympia and Le déjeuner... had received.

|

| Manet, Young Lady, 1866, Metropolitan |

|

What was Manet’s relationship to Victorine? They could have met in the studio of Thomas Couture, Manet’s painting teacher. Born in 1844, Meurent started modelling there at age 16 and even may have taken lessons with Couture. According to her wikipedia biography, Victorine also played guitar and violin, and sang occasionally. She came from a family of minor artisans, and was probably not as poor as many painters’ models at that time.

|

| Manet, The Street Singer, 1862, Boston Museum of Fine Arts |

Manet’s first painting of her was The Street Singer. She looks shy, hurried and slightly guarded. Her brown dress is rumpled as she carried a guitar coming out of a building. She quickly grabs a bite to eat from the cherries in her napkin. Of all the paintings he did of her, this is perhaps the most revealing of Victorine, of who she was and what her life was to become. Artistic and musical, she worked hard.

Shortly after The Street Singer, he painted her portrait, Portrait of Victorine Meurent. She is pretty, resembling the photograph of her that Manet kept in his studio. She looks older than her 18 years in this painting, and she has an air of sophistication. Again she doesn’t resemble women modeled in Manet’s two early masterpieces of 1863, Olympia and Le déjeuner sur l’herbe.

|

| Manet, Portrait of Victorine Meurent, 1862, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

Manet must have loved her for her versatility, the fact she could appear quite differently from painting to painting. Her nickname was La Crevette, meaning “shrimp.” She was quite short and had red or auburn hair. Her eyes appear brown or hazel, while her hair can appear brown, red or of indeterminate color. In the portrait, he brought out all those qualities he saw in her as “beautiful.” Here, she also seems to be the real woman, the woman we see in the photograph collected by Manet. With Victorine as the subject, Manet did not objectify her at all!

|

| Manet, Mlle Victorine in the Costume of an Espada, 1862

|

However, most of the time, Manet pursued Victorine’s image for special effects. She is a prop, much like the fabrics, costumes and materials he kept in his studio. Mademoiselle Victorine in the Costume of the Espada is one of many paintings Manet did in a Spanish theme. Victorine is recognizable as the same woman as in Le déjeuner. (He painted this image a year earlier than Le dejeuner…) She is dressed like a bullfighter, and for the background Manet borrows from bullfighting prints by Goya. Manet was experimenting with raised perspective and compositional space, years before Van Gogh and Munch did the same. The pink cape she holds is study in painting fabric and color.

Was Manet being ironic by turning her into a bullfighter? Perhaps, but he also knew Victorine as a patient and willing model. He’s experimenting dramatically with both color and space here, and perhaps he didn’t have a male model up to task. Perhaps her small body best served his purpose.

My thoughts about Manet and Meurent’s relationship is that it was a strong, professional relationship. Was she his mistress? No. Like a good film director, Manet treated Victorine as the woman who could be cast in many roles. Victorine was to Manet as Diane Keaton was to Woody Allen’s early film career. Victorine was to Manet as Penelope Cruz was to Pedro Almodóvar. Later on, these film directors found other muses.

|

| Manet, The Railway (also called Gare Saint-Lazare), 1872, National Gallery of Art, Washington |

After a pronounced lull in painting Victorine after 1866, Manet painted her again in The Railway of 1872. At this time Victorine was 29, but she looked remarkably younger than she appeared in Olympia and Le Dejeuner. She is a woman who is nostalgic, a woman who looks to the past, while the girl beside her is all excited about the future. She is blasé about the train and wishes the future would not intrude so much into the present. Again, Victorine showed herself to be an actress who could play different roles — in her own standoffish way.

Victorine took up painting in the 1870s and she was accepted into the Salon at least 6 times. The only surviving painting is a portrait called Palm Sunday. It is quite good as a painting, but her style was far more traditional than Manet’s. She models the sitter with traditional, nuanced light and shade to make the face three-dimensional. The sitter turns to the side, which doesn’t really convey the personality. She even projects the plant closer to the picture plane and edge of the painting, giving it significant attention, too While Meurent frequently posed as prostitute, her only painting known today is of a young participant in a religious procession. Victorine was in her 40s by that time, but her choice of subject is ironic if we know of the types of paintings for which she posed.

|

| Victorine Meurent, Palm Sunday, 1885, Musée de l’art et l’histoire, Colombes |

After Manet died in 1884, Victorine went to Suzanne Leenhoff, Manet’s widow, and told her she had been promised more income from Manet as some of the paintings for which she modeled sold. Suzanne coldly refused her request.

Who was Victorine? She was essentially an honest woman, who made an honest living as a model. She worked hard in art and in music. She had minor successes from time to time, but fought back well when she hit hard times. Victorine sought artistic expression, but not fame or notoriety. Manet definitely wanted public affirmation, not the angry outcry that he was receiving while she was his muse. She modeled for other artists, including Toulouse-Lautrec, who teased her by calling her out as Olympia.

|

| Manet, Olympia, 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

Victorine may have been very interested in projecting Manet’s artistic objectives, but later pursued her own artistic objectives along different lines. (In Le déjeuner sur l‘herbe and Olympia, Manet sought to modernize the themes of Giorgione and Titian of the Renaissance. He remakes them to be of his time, in the style we call Realism.) The audiences who saw these masterpieces probably didn’t know the model‘s identity. They thought nudity portraying mythological themes of the Renaissance or in the guise of goddesses and muses was absolutely fine. Even portraying the prostitute could have been ok, if it had been done tastefully as in Goya’s Nude Maya. However, Victorine played the part too well, conveying the distasteful side of the world’s oldest profession–that she is treated as object, not person. She, herself, probably did not engage in sex for money, but she acted the part so well.

|

| Manet, Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1862-1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

Victorine is the symbol of a time and place. Although interwoven with the men, her frank stare seems to say to the audience, “I don’t give a damn what you think.” Is Manet judging like the 19th century audience did? More likely he recognizes the good and the bad. The advantage is that prostitution is a way to rise above one’s class and make a living. (Like the Valtesse de la Bigne, some women rose from abject poverty to the top of the social world this way.) The bad is the de-personalization that comes with it. My opinion is that Manet often found her to be the best model to make a statement of the ambiguities of modern life that he wished to express.

Throughout his career, Manet sought ways to reconcile the ambiguities of his time. Tomorrow will be Manet’s 185th birthday, and we’re still discussing the treatment of women. So today we witness the women’s march on Washington against the backdrop of Donald Trump’s Inauguration.

(There’s a 19th century French expression: “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” The more things change, the more they stay the same thing.) Please don’t get angry at me for saying it again.

Certainly other models, the actresses and actors of Manet’s oeuvre, also have the detached gaze. Such impersonal expressions went along with the modern, urban life. (Suzon, the barmaid in The Bar at the Folies–Bergère, says it just as well, or even better. But she came later.) Meurent channeled the expression better than almost anyone over time. As Manet’s first important muse, her soul lives on for posterity.

There arenovels about Victorine Meurent, none of which I’ve read: Paris Red, by Maureen Gibbon, Mademoiselle Victorine: A Novel, by Debra Finerman and A Woman with No Clothes, by V.R. Main. She has stirred the imagination of writers more than Manet and his relationship to Berthe Morisot, with whom he was in love. Manet even portrayed Berthe Morisot more often, and in more guises. I think it’s because Victorine took part in two of his three most famous paintings.

Here are three more blogs about Victorine Meurent and Manet.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Dec 26, 2016 | Baroque Art, birds, Carel Fabritius, Delft, Vermeer

|

| Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch, 1654 |

“We have art in order to not die for the truth.” Donna Tartt quotes Nietzche in the opening of one of her chapters in The Goldfinch, an epic journey of life novel. It’s taken me all year, but finally, I’ve finished reading The Goldfinch (need a long plane trip to do that). The entire drama is centered around a missing painting, or, shall we say, a stolen painting in the hands of the narrator.

It’s interesting that Donna Tartt chose a painting to be the symbol of her protagonist. Carel Fabritius’ The Goldfinch — the painting — is a bird chained on a pedestal. He’s stationary–as if saying “I am.” At one point, the author gives a hint of original purpose for the painting, that it was a signpost for a tavern. (That’s the type of things art historians write about, but Tartt writes about the painting in a much more interesting way.)

Because I’m not a literary scholar, I can’t comment on Tartt’s writing. But as an art critic, she understands why we need art in our lives. The quotes in the book are full of wisdom about the intersection of art and humankind, art and life, truth and life. She understands art as well as any art historian. Here are some quotes from the book:

“If our secrets define us as opposed to the face we show the world: then painting was the secret that raised me above the surface of life and enabled me to know who I am.”

The voice in the book, Theo Decker, starts when he’s a 13-year old. His life is a traumatic one, and he soon becomes an orphan.

The voice in the book, Theo Decker, starts when he’s a 13-year old. His life is a traumatic one, and he soon becomes an orphan.

“If every great painting is really a self-portrait what if anything is Fabritius saying about himself?” (Here’s the other blog I wrote about birds by multiple artists.)

She describes qualities the goldfinch has that are like human qualities: “It’s hard not to see the human in the finch. Dignified, vulnerable. One prisoner looking at another.” Later on Tartt writes: “… even a child can see its dignity: thimble of bravery, all fluff and brittle bone. Not timid, not even hopeless, but steady and holding it’s place. Refusing to pull back from the world.”

Before coming to this conclusion, the protagonist makes these smart observations about life:

“Can’t good sometimes come from strange back doors?”

“Coincidence is God’s way of remaining anonymous.”

As Theo goes through so many trials and tribulations, we think that it’ll end in tragedy and that he’ll be doomed. Of Theo’s relationship to Pippa, the narrator says: “Since our flaws and weaknesses were so much the same, and one of us could bring the other one down way too quick.” It seems this truth is often the case in many relationships. Kitsey, to whom Theo is engaged, seems quite the opposite of Theo in so many ways, shallow and disengaged. Do such opposites anchor each other and keep them from going to deeply in the wrong direction? (The answer, well, is that his transformation comes without her in the picture)

Tartt also makes us think about beauty and truth.

“Beauty alters the grain of reality.”

“It’s not about outward appearances but inward significance.” The narrator explains at the end that the “only truths that matter are the ones I don’t, and I can’t, understand.” So what does the painting mean for him? “Patch of sunlight on a yellow wall. The loneliness that separate every living creature from every other living creature,” This description can be applied to the goldfinch, and how Theo sees his life.

“There’s no truth beyond illusion. Because between reality on the one hand, the where the mind strikes reality, there’s a middle zone, a rainbow edge where beauty comes into being, where two very different surfaces mingle and blur to provide what life does not; and this is the space where all art exists, and all magic.”

On p. 569, Horst describes the Fabritius painting: “It’s a joke….and that’s what all the very greatest masters do. Rembrandt, Velazquez. Late Titian…..They build up the illusion, the trick–but step closer? it falls apart into brushstrokes. Abstract, unearthly. A different and much deeper sort of beauty altogether. The thing and yet not the thing.” “There’s a doubleness. You see the mark, you see the paint for the paint, and also the living bird.” “He takes the image apart very deliberately to show us how he painted it. Daubs and patches, very shaped and handworked, the neckline especially, a solid piece of paint, very abstract.” What lovely descriptions of the intersection of realism and abstraction.

Why is The Goldfinch so touching to so many people, both the book and the painting? Theo and Tartt express deep appreciation for the restoration specialists, like Hobie, Theo’s caretaker and business partner. Hobie lovingly bring works back to their original state. In the book, there’s an intersection between truth and illusion, but there’s also the understanding that great art is at once realistic and abstract.

The Goldfinch is a trompe l’oiel painting, but it is so much more.

“Its the slide of transubstantiation where paint is paint and yet also feather and bone. It’s the place where reality becomes serious and anything serious is a joke. The magic point where every idea and it’s opposite are equally true.” As I often say, art is about the reconciliation of opposites, and Theo and Tartt achieve this in The Goldfinch.

In Dutch art history, Fabritius, a pupil of Rembrandt stands in between his teacher and the master of Delft, Vermeer. Vermeer’s simplicity could not be imagined without The Goldfinch, and one wonders if he was in fact Vermeer’s teacher. Fabritius lived in Delft at the time of his death in in 1654. He died in a gunpowder explosion when he was only 32. Gerry, a blogger in Great Britain, did a tremendous job of explaining Fabritius and his painting.

I always enjoy reading books that center around a painting. But this novel is not about how or why the painting was made. It is about the journey of the painting and it’s presumed caretaker, what it does for him through his growing years and into several years of adulthood. It is a symbol of his life, his hopes and the man he became.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2021

by Julie Schauer | Apr 8, 2016 | 18th Century Art, Elizabeth Vigée-LeBrun, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Portraiture, Women Artists

|

| Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, Self-Portrait with Cerise Ribbons, c. 1782, Kimbell Art Museum |

Vigée-Le Brun: Woman Artist of Revolutionary France is major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum until May 15. Élisabeth Louise Vigée-Le Brun’s Self-Portrait from the Kimbell Art Museum explains her quite well. She shines with the confidence and elegance of a woman who would eventually become an international superstar. It shows off her top-notch artistic skills. Touches of brilliant red for the ribbon, sash, lips and cheeks to add sensual pizzaz. Portraits are not my favorite genre of painting, but Vigée-Le Brun’s portraits are always dazzling. The light radiating through her earring is just the right touch. One reason we never hear her mentioned among France’s top ten or twenty painters is that she was a painter of royalty who supported the wrong side of the French Revolution. It is only last year that France gave her a major retrospective, although her international reputation was strong back in her day.

|

Jacques-Francois Le Sevre, c. 1774

Private Collection |

Vigée-Le Brun compares well with Jacques-Louis David and the very best French artists of her time. For the most part, she was fairly traditional rather than an innovator. Her style has elements of the late Rococo and Neoclassical styles, but with the addition of some naturalistic features. She was largely self taught, having learned from her painter father before he died when she was 12. Her mother was a hairdresser. She set up her own studio at age 15, supporting herself, mother and younger brother. After her mother remarried, she painted her stepfather, Monsieur Le Sevre (whom she really didn’t like, though I can’t discern it in the painting.) She was only about 19 at the time she painted it, around the same time she entered the Academy of Saint Luke, the painter’s guild.

Vigée-LeBrun was earning enough money from her portrait painting to support herself, her widowed mother, and her younger brother. T – See more at: http://www.nmwa.org/explore/artist-profiles/%C3%A9lisabeth-louise-vig%C3%A9e-lebrun#sthash.AhJDfSMB.dpufsupporting herself, her mother and younger brother. After her mother remarried, she painted her stepfather. The portrait of Monsieur LeSevre, is superb, though the artist was probably no older than 19. Around the same time, she joined the Academy of St. Luke (the painter’s guild). She soon made her way to the top. A few years later, she was called to work at Versailles, becoming the personal painter of Marie Antoinette. She commanded some very high prices for her work.

|

| Joseph Vernet, 1778, Louvre Museum, Paris |

In 1778, she painted Joseph Vernet, a distinguished older painter of seascapes whom she greatly admired. He counseled her to always look at nature. I had seen the Vernet portrait in a NMWA exhibition a few years ago, a monumental exhibition that brought to light many of the gifted female artists of the era. the Met describes Vernet as her mentor, and it’s easy see the affectionate expression in this portrait. It has a wonderful harmony of various blacks and grays.

Painters are sometimes divided into those who are great draftsmen (like Michelangelo and Ingres) or great colorists (like Titian and Rubens). Vigée-Le Brun combines drawing ability and an exquisite sense of color. (There are several drawings in the exhibition.) Vigée-Le Brun’s father, Louis Vigée was a pastel artist and the self-portrait she did in pastel is just lovely. It combines loose, free lines with delicate, subtle modeling to make the face pop out. What other artists can make black, white and gray so interesting?

|

Self-portrait in Traveling Costume

1789-90, pastel, Private Collection |

Marriage, Her Husband and Daughter

In 1776, she married Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun, a painter, art dealer and a great connoisseur who fostered an appreciation of northern artists. He was the grandnephew of Charles Le Brun, founder of the French Academy. Together they traveled to Flanders and the Netherlands to study the northern artists. She was a greater painter than he was, but it was a connection of great mutual benefit for both of them. In 1780, a daughter, Jeanne Julie, was born. Julie became the subject of many of her mom’s paintings. A real gem of the show is the portrait of her daughter looking in a mirror. It simultaneously gives us a frontal and profile view. It is also a very sentimental painting.

|

Julie LeBrun Looking in a Mirror

c. 1786, Private Collection |

One self-portrait by her husband is in the exhibition. He was probably the most important art connoisseur and dealer in France in his time. Pierre Le Brun is credited with writing the most important book on Netherlandish art and elevating the reputation of one of the world’s most popular Old Masters, Johannes Vermeer.

In 1783, Vigee-Le Brun gained entry into the prestigious Royal Academy, one of only four women in the elite group. There was some conflict of interest, because her husband’s profession as an art dealer could have disqualified her. However, King Louis XVI used his influence to promote her. Even at the relatively young age of 28, she commanded higher prices than her peers.

At the time, history painting, meant to instruct and moralize, was considered the highest category of painting. The canvas she submitted for admission into the French Academy was an allegorical piece meant to inspire virtue, Peace Bringing Back Abundance. As the name suggests, prosperity comes from staying out of war. While the classical Grecian style of this painting is not the taste of today, it’s her colors that I love. Unfortunately, peace would not remain in her life and in France for very long.

|

| Peace Bringing Back Abundance, 1780, Louvre Museum, Paris |

When Marie-Antoinette fell from favor and lost her life, Vigée-Le Brun had reason to be afraid. She left France for Italy, with her daughter and without her husband. She was quickly accepted into the Accademia di San Lucca in Florence. She was asked to add her portrait to the the Corridoio Vasariano at the the Uffizi, an obvious sign that her reputation preceded her. This self-portrait in the Uffizi Gallery, painted in 1790, is one of her most famous paintings (below). According to the Metropolitan Museum, the ruffled collar was meant to show her affinity to Rubens and Van Dyke. The cap is reminiscent of self-portraits by Rembrandt, but the brilliant red sash and the use of color contrast is strictly Elisabeth Vigee – Le Brun. It shows greater spontaneity than some of her royal commissions. A few years earlier she had been criticized for breaking with convention by painting self-portraits with an open mouth, making them look less serious.

|

| Self-portrait, 1790, Uffizzi Gallery, Florence |

With her out of the country and the Reign of Terror going on in France, her husband was forced to divorce her. (When the aristocracy lost power, he also lost his major clients.) She remained in exile for 12 years, but painted in the Austrian Empire, Russia and Germany. Her services as a painter were in high demand and she commanded high prices from her lofty, aristocratic clients. In particular, she painted many Russian aristocrats, including one owned by the National Museum for Women in the Arts which is not in the current exhibition.

Portraits of Russian and Foreign Aristocrats

|

Duchess Elizabeth Alexyevna, 1797

Hessische Hausstiftung, Kronberg |

Many of the paintings on view at the Met are from private collections, suggesting that many portraits may still be owned by descendants. None of her paintings from Russian museums are on loan to the United States, because of diplomatic problems at this time. The exhibition going to National Gallery of Canada in June will have several paintings from the Hermitage that are not in the New York show. These paintings were included in the Paris, where the exhibition started.

Vigée Le Brun painted at least five portraits of Grand Duchess Elizabeth Alexyevna, but the example here has a sumptuous red cushion and a transparent purple shawl, that sets off nicely against white skin, dress and long flowing hair.

|

Duchess von und zu Liechtenstein as Iris

1793, Private Collection |

Vigée Le Brun also enjoyed depicting personifications and allegory, as did many of the artists of this era. At one time she painted her daughter as the goddess of flowers, Flora. When she painted the beautiful Duchess von und zu Liechtenstein, she imagined her as Iris, the goddess of the rainbow. The colors shine brightly, though a rainbow which I expected to discern in real life, at the exhibition can’t be found in the painting.

In general, she greatly flattered her sisters. It would seem that she only painted women who were beautiful. At the Metropolitan show, about 5/6 of the paintings portray female sitters. She carefully considered all props, and how to reflect the personality of the sitter. Vigée Le Brun figured out how to bring out their best features and reflect the personality of the sitter.

|

| Countess Anna Ivanova Tolstaya, 1796, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa |

The use of materials, props and settings is crucial to her goals. A portrait of Countess Anna Ivanova Tolstaya has a large outdoor background taken from the natural world, a Romantic setting. The countess looks dreamy and wistful. In general, there is a very wide variety to the types of colors she used, and the harmonies she created. The National Museum of Women in the Arts currently has an exhibition on Salon Style, which includes portraits by Vigee Le Brun, among other French women artists. An unattributed pastel of Marie Antoinette would appear to be by Vigee-Le Brun, too, or at least copied from a painting by her.

Vigée-Le Brun’s Legacy and Queen Marie-Antoinette

From a strictly historical perspective, however, her connections to the French Royal family may be the most important contribution. From her many portraits of Marie-Antoinette, historians can look for clues into the life and character of this demonized queen. It’s difficult to figure out if Marie-Antoinette was really as bad a person as history portrays her. I saw the Kirsten Dunst movie about her and more recently a play about her, both of which show her as a tragic figure who was a foreigner and really didn’t really know how to fit into the world into which she married. We may never really know. Marie-Antoinette may have wanted Vigée Le Brun to soften her image. Several portraits of her are in the exhibition. The bouffant, powdered hairdos don’t beautify her to me. Marie-Antoinette and Her Children, a large, flamboyant group portrait loaned shows the young queen with three children and an empty cradle. It emphasizes that the Austrian-born queen had recently lost a child. So even in this sumptuous setting there is great sadness and loss.

|

Marie-Antoinette and Her Children, 1787, Musée National des

Chateaux de Versailles et de Trianon |

Madame Royale and the Dauphin Seated is a portrait of the two oldest children when the were around 3 and 6 years old. The princess’ satin dress is brilliant display of Vigee Le Brun’s skill at portraying texture. The pastoral background is nostalgic and adds to the sense of innocence. It gives no hint of what’s to come. The prince died of tuberculosis in 1789, ate age 7. (Dauphin County, Pennsylvania is named after him.) Marie-Therese, named for her grandmother, was imprisoned between 1789 until 1795. She was queen 20 days in 1830 and lived until 1851, but generally had a very sad life. There is actually one landscape painting in the exhibition (and there were several landscape drawings in the Paris exhibition), but Vigee Le Brun is first and foremost a portrait painter.

|

Madame Royale and the Dauphine Seated, 1784, Musee National

des Chateaux de Versailles et de Trianon |

|

Between 1835 and 1837, Vigée Le Brun wrote her memoirs. A remarkably great artist and a remarkable woman, she lived to be 86. She is appreciated much more than for her paintings of many Marie – Antoinette. When I took a college Art History class that started with the French Revolution and went to about 1850, we didn’t cover Vigée-Le Brun. David, the academic teacher who influenced so many students, was treated like a god in my class. I find it curious that Vigée-Le Brun remained completely loyal to the royal family, while David was such a politician. He painted for the king, turned into a revolutionary and then easily switched gears to become Napoleon’s artist. He secured his reputation for posterity. With this exhibition traveling to Paris, New York and Ottawa, Vigée-Le Brun’s reputations will go up a few notches, putting her in a rank equal rank to that of David. The Metropolitan has a complete list of paintings in the exhibition. See the Met’s video of her.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 16, 2016 | Art and Science, Greater Reston Arts Center, Ramon Cajol, Rebecca Kamen, Steven J. Fowler, Susan Alexjander, theory of relativity

|

| Rebecca Kamen, NeuroCantos, an installation at Greater Reston Arts Center |

Six years ago, The Elemental Garden, an exhibition at Greater Reston Arts Center (GRACE) prompted me to start blogging about art. Like TED talks, the news of something so visually fascinating and mentally stimulating as Rebecca Kamen’s integration of art with sciences needs to spread. GRACE presented her work in 2009 and did a followup exhibition, Continuum, which closed February 13, 2016.

|

| Rebecca Kamen, Lobe, Digital print of silkscreen, 15″ x 22″ |

Like the Elemental Garden, Kamen’s new works visually evoke and replicate scientific principles. For the non-scientist and the scientist, the works and their presentation are fascinating. Kamen worked with a British poet and a composer/musician from Portland, Oregon, each with similar intellectual interests.

Two prints included in the show create a dialogue between her design and the words of poet Steven Fowler. I like how the idea of gray matter is overlapped by darker conduits, in Lobe, above. There’s a wonderful sense of density and depth.

While her last exhibition at GRACE was mainly about the Periodic table in chemistry, this time Rebecca Kamen’s exhibition included additional themes such as neural connectivity, gravitational pull, black holes and other mysteries of the universe. Why use art to talk about science? In a statement for Continuum, Kamen starts with a quote by Einstein: “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science.”

Both art and science are creative endeavors that start with questions. One time Kamen told me that she knows there is some connection between the design of the human brain and the design of the solar system, that has not yet been explained. NeuroCantos, the installation shown in the photo on top, explores this relationship. Floating, hanging cone-like structures made of mylar represent the neuronal networks in the brain, while circular shapes below symbolize the similarity of pattern between the brain and outer space, the micro and macro scales. It investigates “how the brain creates a conduit between inner and outer space through its ability to perceive similar patterns of complexity,” Kamen explained in an interview for SciArt in America, December 2015. The installation brings together neuroscience and astrophysics, but it’s initial spark came from a dialogue with poet Fowler. (They met as fellows at the Salzburg Global Seminar last February and participated in a 5-day seminar exploring The Art of Neuroscience.)

|

| Rebecca Kamen, Portals, 2014, Mylar and fossils |

Nearby another installation, Portals, also features suspended cones hanging over orbital patterns on the floor. The installation interprets the tracery patterns of the orbits of black holes, and it celebrates the 100th anniversary of Einstein’s discovery of general relativity. It’s inspired by gravitational wave physics. To me, it’s just beautiful. I can’t pretend to really understand the rest. The entire exhibit is collaborative in nature, with Susan Alexjander, composer, recreating sounds originating from outer space. The combination of sound, slow movement and suspension is mesmerizing.

Terry Lowenthal made a video projection of “Moving Poems” excerpts from Steven Fowler’s poems and a quote from Santiago Ramon y Cajal, artist and neuroscientist.

There are also earlier works by Kamen, mainly steel and wire sculptures. With names like Synapse, Wave Ride: For Albert and Doppler Effect, they obviously mimic scientific effects as she interprets them. Doppler Effect, 2005, appears to replicate sound waves drawing contrast in how they are experienced from near or far away.

|

| Rebecca Kamen, Doppler Effect, 2005, steel and copper wire |

Kamen is Professor Emeritus at Northern Virginia Community College. She has been an artist-in-residence at the National Institutes of Health. She did research Harvard’s Center for Astrophysics and at the Cajal Institute in Madrid. Her art has been featured throughout the country; while her thoughts and concepts have been shared around the world.

For more information, check out www.rebeccakamen.com, www.oursounduniverse.com (Susan Alexjander) and www.stevenjfowler.com

The Elemental Garden

|

| Elemental Garden, 2011, mylar, fiberglass rods |

To the left is a version of The Elemental Garden in Continuum. An identical version is in the educational program of the Taubman Museum of Art, Roanoke, VA.

(The following is how I described it while writing the original blog back in 2010) Sculptor Rebecca Kamen has taken the elemental table to create a wondrous work of art. The beautiful floating universe of Divining Nature: The Elemental Garden–recently shown at Greater Reston Area Arts Center (GRACE)–is based on the formulas of 83 elements in chemistry. Its amazing that an artist can transform factual information into visual poetry with a lightweight, swirling rhythm of white flowers.

According to Kamen, she had the inspiration upon returning home from Chile. After 2 years of research, study and contemplation, she built 3-dimensional flowers based upon the orbital patterns of each atom of all 83 elements in nature, using Mylar to form the petals and thin fiberglass rods to hold each flower together. The 83 flowers vary in size, with the simplest elements being smallest and the most complex appearing larger. The infinite variety of shapes is like the varieties possible in snowflakes; the uniform white mylar material connects them, but individually they are quite different.

|

| Rebecca Kamen, The Elemental Garden, 2009, as installed in GRACE in 2009 (from artist’s website) |

One could walk in the garden and feel a mystical sensation in the arrangement of flowers, as intriguing as the “floral arrangement” of each single element. After awhile I discovered that the atomic flowers were installed in a pattern based upon the spiral pattern of Fibonacci’s sequence. Medieval writer Leonardo Fibonacci and ancient Indian mathematicians had discovered the divine proportion present in nature. This mystical phenomenon explains the spirals we see in nature: the bottom of a pine cone, the spirals of shells and the interior of sunflowers among other things. Greeks also created this pattern in the “golden section” which defines the measured harmony of their architecture. Kamen wanted to replicate this beauty found in nature

Kamen likened her flowers to the pagodas she had seen in Burma. However, there is an even more interesting, interdisciplinary connection. Research on the Internet brought Kamen to a musician, Susan Alexjander of Portland, OR, who composes music derived from Larmor Frequencies (radio waves)emitted from the nuclei of atoms and translated into tone. Alexjander collaborated, also, and her sound sequences were included with the installation. Putting music and art together with science mirrors the universe and it is pure pleasure to experience this mystery of creation.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 13, 2016 | Ceramics, Contemporary Art, Eva Zeisel, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Industrial Design, Isamu Noguchi, Karen Karnes, National Museum for Women in the Arts, Ruth Asawa, Surrealism

|

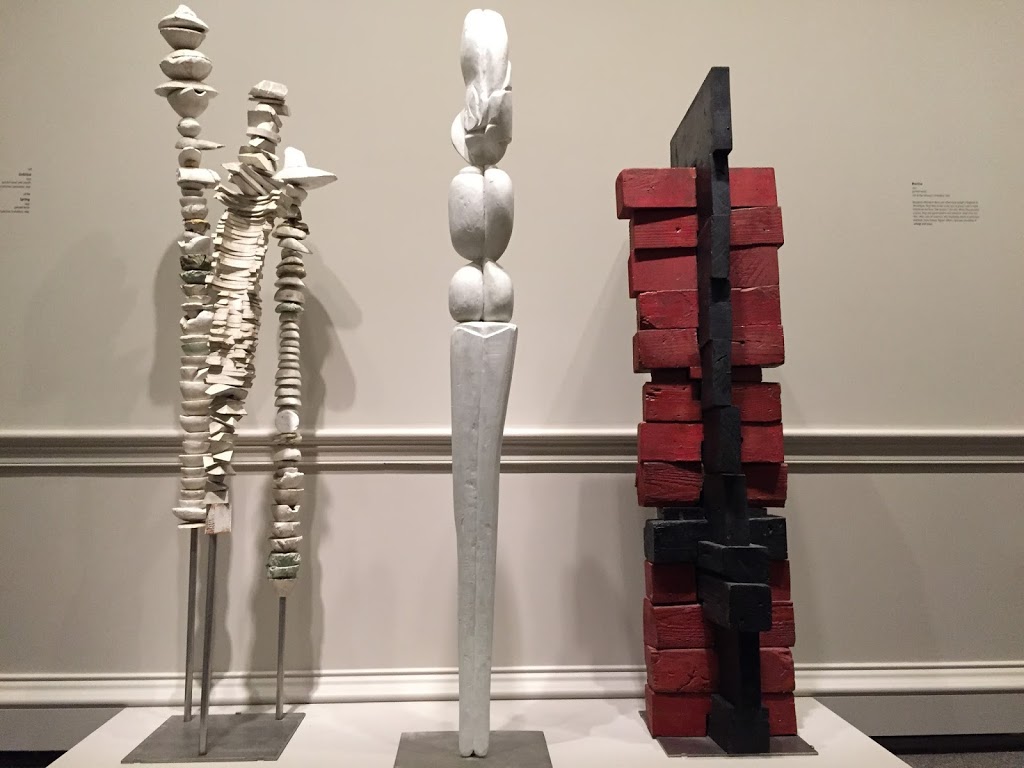

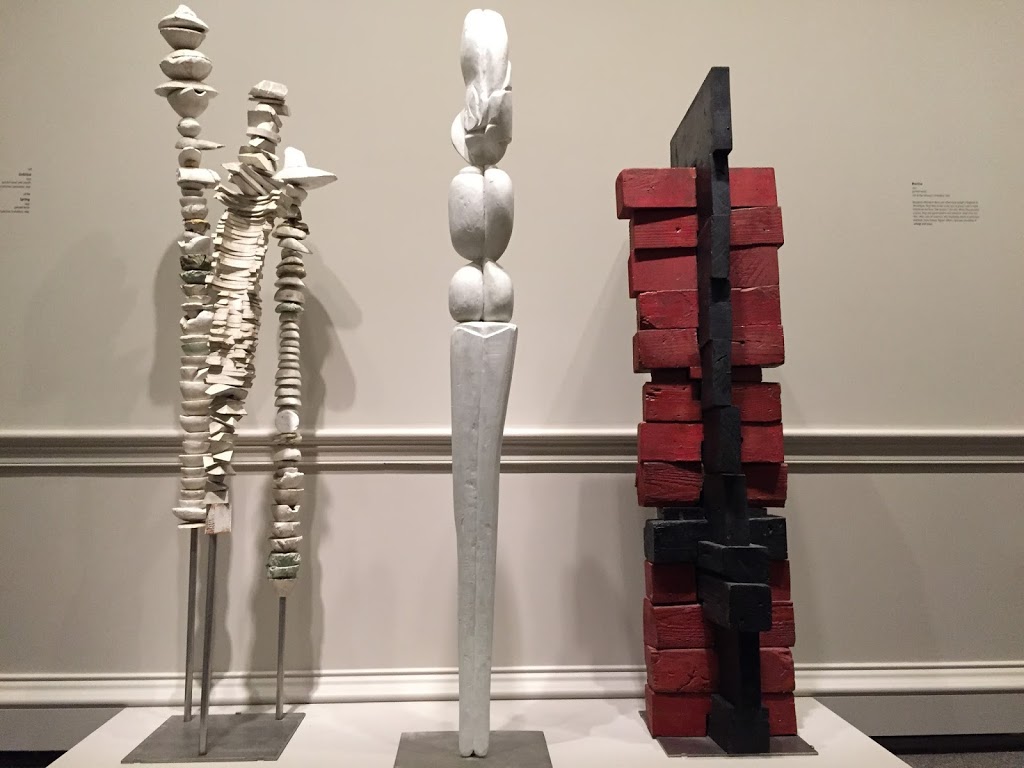

Isamu Noguchi, Trinity, 1945, Gregory, 1948, Strange Bird (To the Sunflower)

Photo taken from the Hirshhorn’s Facebook page |

Biomorphic and anthropomorphic themes run through quite a few exhibitions of modern artists in Washington at the moment. The Hirshhorn’s Marvelous Objects: Surrealist Sculpture from Paris to New York has several of the abstract, biomorphic Surrealists such as Miro and Calder. The wonderful exhibition will come to a close after this weekend.

Isamu Noguchi’s many sculptures that are part of Marvelous Objects deal with an unexpected part of the artist’s life and work. Noguchi was interned in a prison camp in Arizona for Japanese-Americans during World War II. Whatever the horrors of his experience, he dealt with it as an artist does — making art and using creativity to express the experience by transforming it.

|

| Isamu Noguchi, Lunar Landscape, 1944 |

Lunar landscape comes from immediately after this difficult time period. The artist explained, “The memory of Arizona was like that of the moon… a moonscape of the mind…Not given the actual space of freedom, one makes its equivalent — an illusion within the confines of a room or a box — where imagination may roam, to the further limits of possibility and to the moon and beyond.” It’s like taking tragedy and turning it into magic.

|

| Strange Bird (To the Sunflower), 1945 Noguchi Museum, NY |

|

|

The most interesting piece from this period is Strange Bird (To the Sunflower), 1945. It is pictured here 2x — on top photo, right side, and from a different angle on the left, from a photo in the Noguchi Museum. Between 1945 and 1948, Noguchi made a series of fantastic hybrid creatures that he called memories of humanity “transfigurative archetypes and magical distillations.” Yet the simplicity and the Zen quality I expect to see in his work is gone from this time of his life.

From the beginning of time, “humans have wanted a unifying vision by which to see the chaos of our world. Artists fulfill this role,” said Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto.

I’m reminded of the ancient Greeks who created satyrs and centaurs to deal with their animal nature. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there’s a small Greek sculpture of a man and centaur from about 750 BCE, the Geometric period. The man confronting the centaur seems to be taming him or subduing his own animal nature. Like Noguchi’s sculpture, it has hybrid forms and angularity, but it’s made of bronze. Noguchi’s sculpture is of smooth green slate, which gives it much of its beauty and polish.

|

| Man and Centaur, bronze, 4-3/4″ mid-8th century BCE Metropolitan Museum |

Noguchi was a landscape architect as well as a sculptor. When designing gardens, he rarely used sculpture other than his own. Yet he bought garden seats by ceramicist Karen Karnes. A pair of these benches by Karnes are now on display at the National Museum for Women in the Arts’ exhibition of design visionaries. Looking closely, one sees how she used flattened, hand-rolled coils of clay to build her chairs. The craftsmanship is superb. It’s easy to see how her aesthetic fit into Noguchi’s refined vision of nature.

|

| Karen Karnes, Garden seats, ceramic, from the Museum of Arts in Design, now at NMWA |

|

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 10, 2016 | 20th Century Art, Constantin Brancusi, Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi, Louise Bourgeois, Sculpture, Surrealism

“Contemporary and ancient art are like oil and water, seemingly opposite poles….now I have found the two melding ineffably into one, more like water and air.” Hiroshi Sugimoto, Japanese artist

|

| Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1952, Spring, 1949 and Mortise, 1950 National Gallery of Art |

|

|

Two separate exhibitions in Washington at the moment illustrate the commonality of modern art and prehistoric — especially in sculpture. The me, that theme resonates with two sculptors who lived through most of the 20th century, Louise bourgeois and Isamu Noguchi. The National Gallery has a two-room exhibition Louise Bourgeois:No Exit, and Noguchi (hopefully in another blog)‘s works are part of the Hirshhorn’s exhibition, Marvelous Objects: Surrealist Sculpture from Paris to New York.

|

Constantin Brancusi, Endless Column,1937

|

|

|

Three sculptures by Bourgeois in the National Gallery are what she called personages. As a whole they’re not unlike the archetypal images of Henry Moore or Constantin Brancusi. Among these three works are a group of three piles of stones resting on stilts. It’s one of the Bourgeois sculptures that

|

Barbara Hepworth, Figure in Landscape,cast 1965

|

appears simple and somewhat primitive. Untitled is above on the left. The stones stand tall and top heavy; they seem to be wearing big hats. I’m reminded of the precarious state of human existence. I am also thinking of the top-heavy candidates in the recent Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary, weak on bottom and they may fall. Aesthetically these works form a link to Brancusi’s birds on pedestals and the Endless Column, Targu Jui, Romania, part of a memorial for fallen soldiers in World War I.

The sculpture of Spring center above is reminiscent of a woman, or of the ancient Venus figures, which date to the Paleolithic era, around 20,000 BCE. It can be compared the the elongated marble burial figures from prehistoric, Cycladic Greece as well.

|

| “Venus” figures from Dolni Vestinici, Willendorf, Austria and Lespuge, France |

|

|

|

A version of Alberto Giacometti’s bronze Spoon Woman from the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas is in the surrealist exhibition (Example below from Art Institute of Chicago). Giacometti made this archetypal image in 1926/27, but the bronze was cast in 1954. Henry Moore’s Interior and Exterior Forms, is a theme he did over and over, is an archetype of the mother and child.

|

| Giacometti, Spoon Woman, 1926/27, cast |

1954 |

In 1967, the Museum Ludwig, founded by chocolate manufacturers in Cologne, Germany, asked for one of her sculptures to be replicated in a single large piece of chocolate. She chose Germinal, its name suggestive of germination and new beginnings. (Germinal is also the name of Emile Zola’s famous French novel of 19th century coal minors. I wouldn’t put it past her to be referring to the story, but don’t have an idea as to how and why)

|

| Germinal, 1967, promised gift of Dian Woodner, copyright |

|

|

Bourgeois, who died in 2010, lived to be 98 years. She continually worked and invented anew. In time, I think she will be considered a giant among the sculptors of the 20th century, on par with Moore, Brancusi and Calder. Her art was more varied than the others and she defied categorization and/or predictability. However, certain themes seemed to carry her for long periods of time, such as the personages of her early to middle period and the cells she did late in her life. She worked both vary large and very small and with an infinite variety of materials including fiber. She grew up in a family which worked in the tapestry business, primarily repairing antique tapestries. To her, making art was making reparations making peace with the past. Some wish to put her in the category of Surrealism, but she calls herself an Existentialist, in the philosophical realm of Jean-Paul Sartre. Looking at some of the drawings in the National Gallery and how she explained it does give a clue into the existential thoughts and feelings.

|

| Spider, 2003 (not in exhibition) |

One of Bourgeois’s best-known themes was the spider, having done several monumental statues in public places. The spider stands for the protective mother, and her version of the archetype, as it also alludes to the weaving activity in her family. It is large and embracing but can also have a dark side. I like best the spiders that combine the metal sculpture with the delicate tapestry figures. The delicacy and litheness of her spider people remind me of the wonderful organic acrobat sculptures from ancient Crete.

|

| Bull-leaping acrobat, ivory, from Palace at Knossos, Crete, c. 1500 BCE |

Bourgeois deals with metaphors. She calls sculpture the architecture of memory. She is poetic, but she’s also quite humorous. She also made a sculpture series of giant eyes. She describes eyes mirrors reflecting various realities. I’m reminded that in ancient times, the eyes were the mirrors of a person’s soul. As different as her works may be, she portrays a consistent voice and aesthetic throughout her career.

|

| Eye Bench, 1996-97, Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle |

When I went to the Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle back in 2010, a friend of mine from California and I came upon her Eye Benches. We sat down and enjoyed it. She designed three different sets of eye benches made of granite. In the end, it seems Bourgeois used her art to make sense of her very complicated world and our experience of that world. Sometimes she seems to laugh at it all, so this experience calls for a good laugh and relaxation.

|

| Louise Bourgeois, Eye Bench, Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle. |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Dec 13, 2015 | Gauguin, Picasso, Rouault

|

Paul Gauguin, NAFAE faaipoipo (When Will You Marry?) 1892

Rudolph Staechelin Collection |

The Phillips Collection’s latest loan exhibition, “Gauguin to Picasso: Masterworks from Switzerland,” draws upon a pair of collections assembled by two prominent but very different Swiss art collectors. To me, the theme of dualism, pairs and split identities stands out strongly. The exhibition highlights one of Gauguin’s most famous paintings, When are You to be Married? — a painting that recently was sold. (The Staechelin and Im Oberstag collections of modern art are normally on display at the Basel Kunstmuseum. Here’s an article for background on the collectors why the paintings are traveling.)

Like so many other paintings by Gauguin, the two women in this infamous painting express two realities, which could represent the split identities within Tahitian society. He painted it during his first stay in Tahiti in 1892. The woman in front is natural, organic, relaxed and colorful in her red skirt. The orchid in her hair was said to suggest that she is looking for a mate. A woman behind is taller, more severe and covered in a pink dress buttoned to the top–an influence of Western missionaries. The woman in back has a bigger head than the woman in front. Does he mean to imply that she dominates? Or, is Gauguin imagining a single Tahitian woman who is torn between her native identity and the invasion of western civilization.

|

| Eugene Delacroix, Women of Algiers, 1834, The Louvre |

The woman in front may be inspired by one of the very beautiful, sensual women painted in Delacroix’s Women of Algiers, one of my all-time favorite paintings. (Delacroix was allowed into the mayor’s harem to sketch the women–pictured at right. Like Gauguin, Delacroix was European observing women in an exotic, foreign land.)

|

| Gauguin, Self-Portrait, 1889, NGA |

|

|

|

|

In his self-portraits and so much of his art, Gauguin expresses the split nature in mankind, the areas where there is inner conflict. Symbolist Self-Portrait at the National Gallery of Art (NGA), Washington, is a divided person, both a saint and a sinner. He has a choice in the matter, and we wonder what he’ll choose.

The two Tahitian women are different, yet blended. Warm brown skin tones unite them and the hot red skirt of the “natural” native woman flawlessly flows into the warm pink of the stiffer, “civilized” woman. The colors blend and contrast simultaneously into a beautiful harmony. (Is it surprising that this picture was the most expensive painting ever sold? Rumor has it that it was purchased by a Qatari for Qatar Museums.)

|

| Georges Rouault, Landscape with Red Sail, 1939, Im Obersteg Foundation, permanent loan to the Kunstmuseum Basel. Photo © Mark Gisler, Müllheim. Image © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris |

Other artists in this exhibition continue the theme of duality and split personality. Early 20th century Expressionist Georges Rouault was honest about his identity as a person belonging in another century, the age of the cathedrals. His heavily-outlined Landscape with Red Sail uses colors reminiscent of the colors in stained glass and the way stained glass is divided by lines of lead. Yet, his paint is applied in a very rough, heavy manner, hardly like the smoothness of glass. His beautiful seascape does, however, evoke the light of a sunset peaking behind the sailboat–like the light filtering in medieval churches.

|

| Alexej Jawlensky, Self-Portrait, 1911 Im Obersteg Collection |

|

|

The Expressionist painter Alexej von Jawlensky was a Russian living in Switzerland, in exile there during World War I. There’s a haunting quality to his Self-Portrait, left. Jawlensky and Im Obersteg had a strong friendship throughout his career.

One side of a Picasso painting features a woman in a Post-Impressionist style, “Woman At the Theatre,” and the other side has a sad woman, The Absinthe Drinker, from the beginning of the “Blue period.” Both were painted in 1901. They could not be more different from each other. Picasso was very experimental at that

|

| Picasso, The Absinthe Drinker, 1901 Im Obersteg Collection |

|

|

time of his life and in his career.

Expressionism is a large part of the exhibition, especially with Wassily Kandinsky, Chaim Soutine, Marc Chagall and Alexej von Jawlinsky. Swiss Symbolist Ferdinand Hodler shares with us his experience of love and death in a group of paintings of his dying lover Valentine Gode-Darel. It is difficult to watch and for him painting may have been an attempt to make peace with the awful situation.

The series of paintings by Hodler are some of the most powerful in the exhibition because we experience the unfolding of a tragedy. Gode-Darel died of cancer in

|

| Ferdinand Hodler, The Patient, painted 1914, dated 1915. The Rudolf Staechelin Collection © Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler |

1915, a year after diagnosis. The three paintings of rabbis by Marc Chagall continue in the theme of portraiture.

There are very fine small paintings by Cezanne, Monet, Manet, Renoir and Pissaro, two beautiful landscapes by Maurice de Vlaminck. Van Gogh’s, The Garden of Daubigny, 1890 is one of three he did of the same subject weeks before his death. The black cat in the painting is small but curiously out of place. The 60 paintings on view, on view until January 10 — are worth the trip to the Phillips. Here are some of the best photographs of the paintings in the show. These Swiss collections complement the Phillips own marvelous collection of early Modernism. It is curious that the Swiss collections don’t show the greatest of all 20th century Swiss artists, Paul Klee.

|

| Vincent Van Gogh. The Garden of Daubigny, 1890 Rudolf Staechelin Collection |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by admin | Dec 13, 2015 | Gabriel Dawe, Janet Echelman, Jennifer Angus, John Grade, Maya Lin, Patrick Dougherty, Tara Donovan, The Renwick Gallery

|

| Tara Donovan, Untitled, 2014 |

One afternoon last month I suddenly arrived in Cappadocia, or least that’s what it seemed. I didn’t actually go there, nor have I ever been there except through pictures of that ancient Turkish landscape. However, I spent my time going to the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery which had just re-opened with an exhibition entitled Wonder.

|

| Gabriel Dawe, Plexus 1A |

The works speak for themselves, as they’re huge installations that recall the wonders of the natural world in a beautiful 19th century building that recently underwent restoration.

Tara Donovan’s construction is made of styrene index cards, toothpicks and glue. As an artist, she may not have been thinking of the same aspects of nature that evoked a response in me. According to Donovan, “It’s not like I’m trying to simulate nature. It’s more of a mimicking of the way of nature.” On the nearby wall, a label quotes Albert Einstein: “The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It’s the fundamental emotion in which starts the cradle of true art and true science.”

Then a rainbow of colors invited me into the next room. Plexus 1A is miles of strings that weave prisms of color into the monumental architecture. Gabriel Dawe is the artist. His design recalls the colors and embroideries of his early life in Mexico City and current home in East Texas. Viewers are invited to take their own photographs. It’s appropriate that the Renwick is a building dedicated to the contemporary crafts, since each of these works of art focuses on the materials and the tremendous time, skill and dedication required for fine art crafts.

|

| Dawe, Plexus1A |

Continuing back on the left side of the building, viewers come into a grandiose room with giant stick weavings by Patrick Daugherty. (A photo of Shindig is on bottom. See the previous blog about one of his interactive and impermanent environmental installations, in Reston, VA)

The Renwick invited nine well-known artists to celebrate the re-opening with works for this exhibition. Each artist was given an entire room for a comprehensive creation, many of them recreating the natural world in a way that helps us understand it better.

|

| John Grade, Middle Fork (interior view) Another view is directly below. |

Upstairs is one of the true giants of nature, a tree. You look at it from the outside or take in the interior view. Artist John Grade, a resident of the Pacific Northwest, engaged an army of volunteers. First, Grade made a cast of a 150-year-old hemlock tree in the Cascade Mountains. Then he reassembled the shape with half a million segments of reclaimed cedar and separated it into sections. Named after the tree’s location in the middle fork of the Snoqualmie River, the tree cast as Middle Fork (Cascades) is 85 feet long.

As you might expect, visitors walk all around the giant tree perched on its side. When the exhibition is over, this “natural” model will be put back in nature, back to the area from which it comes. The artist says the impermanence makes it poignant, since it will eventually decompose.

Quotes are sprinkled on labels throughout the exhibition. Taking her cue from the local area, well-known sculptor Maya Lin (architect of the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial) used fiberglass marbles to recreate the Chesapeake Bay. There are thousands of tine blue-green marbles running floor to ceiling in the entire room. Lin is a geographical artist, and I was reminded her provocative exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art a few years back. Here she has recreated the many estuaries of the bay, which crawl in spider-like patterns up the walls. She re-used the glass her father and other artists had used in Ohio before the glass-making technology improved. The branches of the waterway are delicate and fragile, reminding us that nature itself is fragile, too.

|

| Maya Lin, Folding the Chesapeake |

The Renwick itself is important historically, as it was originally home to the oldest art museum in the District of Columbia, the Corcoran Gallery of Art. The building was almost destroyed. When Jacqueline Kennedy was First Lady, she recognized the building’s significance and used her influence to save the building from the wrecker’s ball.

|

| Jennifer Angus, detail of In the Midnight Garden |

Wonder really hit me in the last room I saw of the exhibition. Artist Jennifer Angus created a beautiful structural design of insects in room covered in vivid, vibrant pink.

In The Midnight Garden” forms several different patterns on walls stained with

cochineal. Using 5,000 insects, she made mandalas on the wall and interspersed them with skulls, reminders of death. “It is not understanding but familiarity that destroys wonder,” is quoted by John Stuart Mill on the wall of another room. In an article I read about the artist, Angus freely admitted that she is no longer in awe of the subject (too much familiarity) but wishes for her viewers to experience the wonder. Throughout the exhibition, words of the philosophers — ancient to modern — makes us stop to ponder.

|

| Jennifer Angus In the Midnight Garden |

One quote really hit me. Ranulf Higden of the 14th century said: “At the farthest reaches of the world often occur new marvels and wonders, as though Nature plays with greater freedom secretly at the edges of the world than she does openly and near us in the middle of it.” For a few short hours, I had escaped to the edges, to the edges of wonder. Locals and visitors in Washington, DC, please go to the Renwick and spend some time in Wonder. Second floor galleries close May 8, 2016, but the 1st floor galleries stay up until July 10, 2016. Leo Villareal, Janet Echelman and Chakaia Booker also have large installations in the show.

|

| Patrick Dougherty, Shindig |

While the art inside of the building continuously amazes, it’s ironic that the wonder and beauty of the building is marred on the outside by a neon sign: “Dedicated to Art.” There’s no need to be so banal since art speaks for itself. (When Philip Kennicott wrote a review for the the Washington Post, he said the neon sign had to go; I wonder if it has been taken down yet.)

by Julie Schauer | Oct 8, 2015 | Photography, Sally Mann

|

| Sally Mann, Candy Cigarette, 1989 |

Sally Mann created controversy two decades ago when she published photographs of her three children, Immediate Family. The photos are beautiful, artistic and arresting. The idea of publishing nude pictures of her children is startling, knowing it can and would attract pedophiles. Did she really think the photos would only attract the photographers and art connoisseurs, as she claims? I would not do the same sharing of my children’s private moments, but should I judge her? To me, art is reconciliation. I look at art to bring opposites together and to negotiate the ambiguities of life, so that is what I am able to find in Sally Mann’s work. She, too, photographed her children to reconcile her need to be a mother without suppressing the artist in her. They are one and the same.

In June Sally Mann spoke at the National Gallery of Art and read excerpts from her book, Hold Still. She uses language exquisitely, much as she composes photographs with great artistry. Like any good biographer, she succeeds in creating mythology. While reading her book, I was thinking isn’t everyone’s life so rich and interesting? It takes the artist to know that, to find that and to bring it to light. Her book is worth the read.

Candy Cigarette hits us in the gut about that time and place of transition into adolescence when we try to rush the process. It expresses the essential difference between her three children marked at a moment of time. The pre-pubescent daughter Jesse stands in center, in an affected pose. The brother is on stilts behind. Virginia, the youngest turns her back to us. The children are together but very separate, each caught in their own version of reality, expressing their individual truths. Composition and placement make the photo work. Jesse’s strong, sharp elbow leads the way to both the brother and the little sister. The angle of the cigarette points to the younger girl who in turn looks at the brother. Of course in this image, she brings out the significance of the moment. In many of her photos, she shows the not-so innocent quality of children, which is why many found it disturbing.

|

| Sally Mann, The New Mothers |

Mann’s photos can be spontaneous or contrived, or a combination of each. A hallmark of her work is balancing the factual with the contrived. She takes happenstance and makes it better. Artists have an ability to see the significance in some event, enshrine it and visually communicate in way that maximizes its significance. They help us, the viewers, to see inner states of mind as eternal truths. Black and white photography — with the emphasis on contrast — sometimes is best.

When looking at The New Mothers, I’m reminded of the very first fine art photographer, Julia Margaret Cameron. The children pose and act, much like Paul and Virginia, a heart-warming photograph of Victorian children acting as if ‘in love” back in 1864. These kids were good at it. Mann’s own daughters are delightfully feminine and express the joy being that way. We appreciate their strength in expressing themselves, as we move into a time period that tries to suppress expression of pride in one’s gender.

|

| Julia Margaret Cameron, Paul and Virginia, 1864 |

When judging on her artistic merit and on what makes her message resonate, I believe her work hits at something quite deep. Rarely does photography approach the artistry of painting, but Sally Mann does by finding what is special in the mundane world. She can see the extraordinary in the ordinary. She sees life in death and death in life.

What I personally look for in art is a way to reconcile opposites. All life is paradox, and Sally’s art hints of this paradox. Art can unify. Life is messy but in art there can be a place where all comes together and we can make peace with messy situations.

Among the descriptions of her children’s pictures are disturbing, unsettling and “suggestive of violence. There’s a wildness about the kids, freedom, strength and to some people, suggestiveness.

|

| Cover photo, Sally Mann, Immediate Family |

At the same time there’s love written throughout. She loves what they represent and what they taught her, as children have much to instruct us about uncontrived living. Perhaps it’s that she portrays them without vulnerability that disturbs some people. When Mann photographed her children, she had their permission (at least until they reached a certain age). Most pictures don’t show them as innocent and vulnerable. As long as they’re under her watchful eye (and the camera’s eye, they are protected by their mother. As she said in her talk, she saw her roles of being an artist and being a mother as one and the same. Her pictures are daily life. All of life is paradox, and her family photos show everyday life with hints of the paradox between innocence and experience.

How and why did she grow up to be an artist? Sally claims to have had free-range parents, but lived at a time before free-range parenting became a buzz word meaning neglect. It was possible in ways it isn’t today. Accordingly, Mann is an artist from a place, Lexington in southwest Virginia, the burial ground of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Her father, husband and one of her daughters attended school at Washington & Lee. She went to the Putney School, where she was influenced by an inspirational photography teacher. She then went onto Bennington, but graduated from Rollins College. She has a masters in Creative Writing from Rollins.

Much of what she writes about and photographs is about her surroundings, her identity with the South, themes of life and death which she views together. Is her account a bit exaggerated? I believe so. I really question if a few of these stories really are true, or if she is merely using her skill at creating a great story. She describers her parents as unemotional people, totally absorbed with matters of the intellect. She wants to feel closeness to her children, perhaps sensing that she needed more from her own parents. Of her ancestors, she feels special connection to the sentimental Welshman, her mother’s father, and to her own father who had a fascination with death. Her father was a country doctor who went to people’s homes and was totally dedicated to his patients. He had an artistic side that his profession prevented him from following. Her mother ran the bookstore of Washington & Lee University. She sees herself as channeling her father’s largely suppressed artistic side — and his obsession with death. He gave her a Leica camera at age 17 and started her on her photography obsession.

Mann and her husband returned to the Shenandoah Valley to raise their children, as it is a place the kids could run wild and in the nude, as she did as a child. A nude photo of Jessie in a swan pose took some work. While watching her kids, with the artist’s eye, she noticed the significance of an event in passing. Then she worked on the photo of it, through trial and error until it reached the near perfect. She grew up playing in old swimming holes. There was nothing unnatural about skinny dipping in this environment.

Being a photographer was her way of being a hand’s-on parent and truthfully I admire this much more than the hard-driving moms who separate their work life from family life and put that life ahead of appreciating the life of child. (I should write another blog about children in art, and about how other artists treat the theme of childhood.)

Mann has published other books, including What Remains, 2003, Deep South, 2005 (photographed in Mississippi and Louisiana), At Twelve, 1988, Still Time, 1994, and Proud Flesh, 2009. She is currently working on photos of the theme of black men.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Aug 24, 2015 | 19th Century Art, Degas, Gustave Caillebotte, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Monet, National Gallery of Art Washington, Paul Durand-Ruel, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Seurat

|

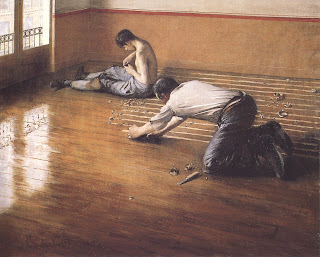

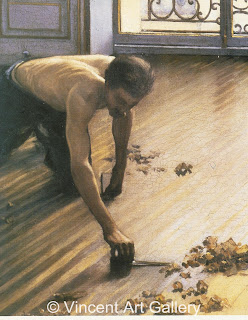

Gustave Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers, 1875 Musée d’Orsay, now on view

at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, |

Right now the National Gallery is having an exhibition of an Impressionist whose reputation has grown over the last 25 years, Gustave Caillebotte. Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye will be on view until October 4.

Caillebotte’s first masterpiece, The Floor Scrapers, was rejected by the Salon in 1875, but accepted into the Impressionist group exhibition the next year. He repaid his dear friends by buying up many of their works and then donating them to the French state after he died. Today many of those paintings belong to Paris’ great early modern museum, Musée d’Orsay.

There are so many reasons The Floor Scrapers is my favorite work by Caillebotte. The composition is extraordinarily well balanced with artful asymmetry on a tilted floor plane. (The invention of photography encouraged artists to look through the viewfinder and frame pictures differently.) There’s also the dignity given to labor, the working man and his beautiful anatomy.

Most it’s incredible to see how Caillebotte painted tactile contrasts on wood in the various stages of sanding, what looks like with or without varnish, and in the light and shadow. Caillebotte painted with more definition and precision than other Impressionists. Yet he illuminates the floor with natural light from the window and we see a wonderful scintillating values, colors and textures. Yellow shines through with touches of blue, but in the distance everything becomes an earthy brown color.

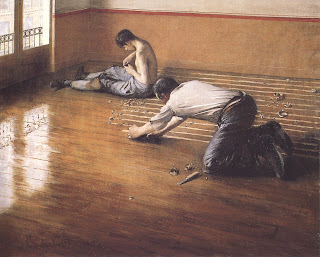

Caillebotte painted another floor scrapers

To understand how good this painting actually is, it’s useful to compare it with another version of floor scrapers that he did. It’s a simpler composition from a different angle, with fantastic lighting effects. Enlarging the photo here will really show off the reflections on the floor. (It isn’t in the National Gallery’s show, but was also part of the 2nd Impressionist exhibition in 1876.)

|

| Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers |

Many of Caillebotte’s other paintings in the exhibition also convey his artful sense of perspective: Le Pont de l’Europe, 1876, for example. He lived at the time that Paris had just experienced a massive rebuilding campaign of boulevards. Paris, A Rainy Day gives an impressive viewpoint of how the new city must have looked to the public, in the eyes of a new bourgeoisie class. Since streets corners were set up in star patterns, the linear perspective goes very deep into multiple vanishing points. A more famous artist, Georges Seurat, borrowed from the composition of Paris: A Rainy Day when he did his iconic painting of Paris on a sunny day, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte.

Other artists of the same time

Monet and Van Gogh are other who shared Caillebotte’s love of deep perspective space. Degas went even further than Caillebotte to exploit the unusual viewpoint. His work can be seen in an important Impressionist exhibition is in Philadelphia, Discovering the Impressionists, until September 13. The exhibit showcases Paul Durand-Ruel, the art dealer who took a gamble and went into great financial risk by buying up Impressionist painters because he believed in them. The exhibit includes Monet’s beautiful Poplars series. However, one of the really important works in the group is by Degas, The Dance Foyer at the Opera on the rue Le Peletier.

|

Edgar Degas, The Dance Foyer at the the Opera on the rue Le Peletier, 1872,

Musée d’Orsay, Paris, now on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art |

Comparing Caillebotte’s Men to Degas’ Dancers

This panoramic ballet scene of dancers offers a wonderful comparison with the Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers. This painting is also asymmetric and appears to look spontaneous, while it is actually exceptionally well-planned. Degas offers more layers of observation: into another room and out the window, through a mirror (?) or another room in the back center. We imagine that the major source of light is a an unseen window to the right. Whites and golds predominate the scene, with touches of blue and orange. Degas’s dancers, though quite strong, may seem delicate next to Caillebotte’s muscular workers.

In truth, Degas’ dancing girls and Caillebotte’s hard-working men are much the same. Their work is a labor of love, as the Impressionists saw it. The same can be said about Caillebotte, Degas, Durand-Ruel and those who left us with a wonderful record of life in Paris in the 1870s. The ballet painting was done in an opera house that destroyed by fire the very next year, probably caused by gaslights.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2024

Recent Comments