by Julie Schauer | Sep 15, 2013 | Ancient Art, Archeology, Architecture, Greek Art, Knossos, Mythology

This summer I finally had the opportunity to go to Greece and see the sprawling Palace at Knossos. Actually, it’s not certain if this site was a palace, administrative center, giant apartment building, religious/ceremonial building, or all of the above. Yet it is so huge that, when discovered in 1900, archeologist Arthur Evans certainly thought he had found a true labyrinth where the legendary King Minos lived and kept his minotaur. The name Minoan for the Bronze Age people who lived in Crete from about 2000-1300 BC has stuck.

|

Covering 6 acres, the palace of Knossos and the surrounding city may have

had a population of 100,000 in the Bronze Age |

According to legend, the king of Athens paid tribute to King Minos by sending him 7 young men and young women who were in turn fed and sacrificed to the half-man, half-bull minotaur. Eventually, with the aid of Minos’ daughter and the inventor Daedalus, Theseus carried a ball of thread to find his way out and to slay the beast.

Although the art at Knossos doesn’t play out the precise myth, carvings and paintings found there involve imagery of bulls. Acrobats jumped and did flips over the animals’ horns, perhaps part religious ritual. It must have been an exciting but highly dangerous sport, and it’s easy to understand that as the story changed over time, later generations would envision a bull-headed monster in a spooky maze.

|

The palace at Knossos is on the hillside, about 5 kilometers from the sea. It was never fortified

Other, smaller palaces have been uncovered on the island. |

Could a prisoner escape without Theseus’ clever trick? Three or possibly four entrances to the palace are off-axis and may have appeared entirely hidden. The building also had windows, light wells, air shafts and ventilation. It was an engineering marvel. No wonder its architect Daedalus became a god to the Greeks. When I was there, it not only felt like a “labyrinth,” but also like “babel.” Its the only place I’d ever been where so many different, unfamiliar languages were being spoken at once. Despite the number of people, it never felt too crowded, because the palace covers six acres.

|

The downward taper of Minoan

columns is unusual but may have

religious significance. The capital

resembles the cushions of Doric

columns of Greece 1000 years later |

The building runs over 5 levels of twists and turns, on the hillside, not on top of a hill. It had 1300 rooms at one time and could have housed as many 5,000 people. There’s a large central courtyard, perhaps where crowds observed the bull-leaping sports. At least four other ancient maze-like palaces have been excavated on other parts of the island, but none as large as Knossos. It is thought that only 10% of Minoan Crete has been excavated and that bronze age Crete had 90 cities. I remember reading that Knossos had a population of at least 100,000 people around 1500 BC. Minoans traded with Egypt and Mesopotamia. Archaeologists have uncovered a Minoan colony in Egypt, Tel-el D’aba, and at Miletus in Turkey.

|

The North Entrance has a restored

fresco of a bull. Minoans were probably

the first to paint in fresco, on wet plaster |

Evans spent 35 years digging, researching and restoring the Palace of Knossos. The restoration reveals the Minoans’ unusual, downward-facing columns, with the narrowest parts on bottom. The earliest builders used the cypress tree and turned it over, so it wouldn’t grow.

There were both small frescoes and life-size frescoes, most of them now in the Archeological Museum in Heraklion, including the bull-leaping fresco. Since Egyptians painted in secco, on dry plaster, it’s believed that Minoans invented the fresco technique of painting on wet plaster. Colors such as blue, red and yellow ochre are very vivid. Generally Minoans painted with a freer and more organic style than the artists of Egypt and Mesopotamia, and often had more naturalistic depictions. However, whenever men or women are found marching with erect stiff postures, it’s conjectured that they functioned as priests and priestesses partaking in the religious rituals. There’s a famous bull-leaping fresco in the local museum.

|

| La Parisienne from Knossos |

|

|

|

Archeologists of today would not take as much liberty and restore as extensively as he did. While Evans pieced together restorations of the palace based on the remnants and shards, he also used his knowledge to restore what is missing. Personally I appreciate that his reconstruction fills in the blanks for us, giving an idea of the size and grandeur of the palace. Also, there’s a great deal to speculate as to what it may have been like to live there. It seems that grains, wine and olive oil may have been milled and pressed at the palace, and also stored in huge pithoi (giant vases) under the floor.

The word labyrinth originates from the labrys, a double-axe related to the double horns of the bull. The language used at the time the first palace was built, around the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, has not yet been deciphered. A second language which appeared at Knossos after mainland Greeks took over the palace after 1500 BC has been translated and is related to the classical Greek language

|

The life-size Prince of Lilies was thought by

Archeologist Arthur Evans to be a priest.

Lilies are common in Minoan imagery. |

All the inscriptions on cylinder seals are commercial records and inventories. Besides myth, the art and artifacts are the best way to figure out the story of these people. Only about 10 percent of the ancient Minoan sites have been excavated. Although the contents of the Archeological Museum of Heraklion, near Knossos, is well known and published, the beautiful pottery and artifacts from the museum of Chania, Crete’s next largest city, have not been published. Getting outside of the cities and into the countryside leaves the impression that the rural life really hasn’t changed too much in 1000 years.

|

The grand staircase at Knossos spans 5 levels. The layout of rooms is organic around a

central courtyard. What seems to be a haphazard arrangement may reflect

building and rebuilding after earthquakes. |

Certain things that date to the Mycenaean takeover of the palace include the Throne Room. Amazing, when the room was discovered, the gypsum throne was intact. Evidence points to the suggestion that the palace had to be abandoned all of a sudden, because of a fire, natural disaster or invasion. Even if this culture eventually went into oblivion for a few hundred years, when the Greek culture re-emerged around the 8th century BC, the Greeks culture retained so much of the Minoan heritage in its art and myth. The myths of the minotaur, Minos, Europa, Theseus, Daedelus and Icarus involve Crete, but so does the story of Zeus who was said to be born in Crete.

|

The Throne Room was found with oldest throne in

Europe, dating to Mycenaean occupation of Crete, around

1450-1400 BC. Evidence shows people had fled suddenly. |

Knossos has a theatre right outside the palace. Performances took place at the bottom of two seating areas set perpendicular to each other, rather than at the end of curved seating area as in later Greek theaters. The ancient Minoans also gave the world two important inventions, indoor plumbing and the potter’s wheel. Wouldn’t it be something if some of the first great Greek literary masterpieces also had an origin here, 1000 years earlier?

Occupation of the palace ended sometime between 1400 and 1100 BC. In the classical era Crete was never as important as Athens, though it is clear that much of what formed later Greek culture came from Crete. A settlement re-emerged in Knossos during Roman times, but during the Middle Ages the population shifted to the city of Heraklion, about 4-5 miles away.

|

| An area outside of the palace has two sets of seats set at a perpendicular angle. Acoustics indicate it was a theater. |

|

|

|

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by admin | Jul 29, 2013 | Architecture, Byzantine Art, Church of Zoohodos Pigi, Crete, Medieval Art, The Greek World

|

| The Church of St. Nicholas in Kourtaliotis Gorge, Crete |

|

| Piles of stones beside St. Nicholas Church |

I cherish my trips with Backroads Travel Co. To me the backroads of Crete are full of surprises, in addition to olive orchards, oleanders and orange groves. On our 3rd day we road from the north to south part of the island. On the way to the beach at Plakias, we bicycled through the Kourtaliotis Gorge. The scenery was breathtaking. A tiny church, St. Nicholas was nestled behind the oleander and the rocks. It seemed to be a place where only a handful of monks prayed a long time ago. Behind it were small piled-up shrines of stone, which resemble votive offerings beside the church.

Crete’s small country churches surprised me, but even smaller churches, or replicas of churches dot the sides of the country roads. These small shrines are all over the place.

|

| A typical memorial erected among the orange groves of Crete |

They’re memorials to loved ones who’ve died and we saw them frequently. One of the hotshot men on our trip, Dennis, reprimanded me for taking photos of graves in churchyards. He told me, “It is bad luck.” (His mother’s family is from Crete.)

The day after we went to the Kourtaliotas Gorge, I experienced bigger surprises — a pair of surprises. Cindy (she lives in Shanghai and was also on the lookout for great photos) & I came upon an abandoned church, seemingly in the middle of nowhere. We both took pictures. Cindy biked on, but I decided to check out the inside.

|

| A 14th century church between the villages of Koufos and Alikianos |

Through the opening of a locked door, I could see that in the center of the church was a fresco of Mary surrounded by two saints. It was too narrow to photograph, but the image was clear but had two big vertical cracks. There were more frescoes to the sides and above, but I really couldn’t see them.

On the outside of the church, a fresco of Mary adorns the pointed arch over a side door. It was badly damaged, but I took a picture (below). It also had painted trim directly under the arch in a beautiful red and blue pattern, and a Greek cross below that.

|

A badly damaged fresco of Mary over the door dates

to the 14th century |

Paintings on the outside of a buildings can’t withstand time and weather.

The sign on the road pointed to Church of the Zoohodos Pigi (in Greek and in English, but what could that possibly mean?) (Later when I was home and looked it up on the Internet, I found a few churches of the same name in Greece.)

This church lies between Alikianos and Koufos. It was built in the early 14th century following an earthquake of 1303, but over the foundations of a 10th century church. (Earthquakes have always been a problem on this island, and in much of the Mediterranean.)

|

| Zoohodos Pigi means “life giving source.” |

El Greco, Greece’s greatest artist in modern times, was from this part of Crete. No one knows exactly where El Greco was born, but his family was from Chania and this church is about 10-20 miles away.

We had already passed a town called Alikianos where there was large new blue and terra cotta colored Greek Orthodox church. It’s easy to understand why a church in the middle of nowhere was abandoned.

I hope that the Church of Zoohodos Pigi will be restored. Apparently it was quite an important church at one time. Zoohodos Pigi means “life-giving source.”

|

| There’s a new Greek Orthodox church in the village of Alikianos |

|

|

|

Just a few miles down the road, I had caught up with Cindy. We had to go up hills too steep for my endurance, and then we turned a corner and stopped. Here came the the biggest surprise of all:

It was lunch time and someone had just dumped a big truck of excess oranges in a goat pen and the goats were chomping away, peels and all. They were chomping like crazy, as if in a contests to finish first. We took many pictures.

How funny to realize that these delicious goat cheeses we’ve been eating in Crete come from animals who feed on oranges, the delicious oranges of Crete!

|

| The Goats’ lunch — so good! |

I discovered both Greek cheeses and orange cake, also called orange pie, on this trip. My grocery store oranges aren’t quite like the oranges I had been eating, and I haven’t found Graviera cheese in any of my local markets. There’s nothing like feeling close to history, the land, the animals and the sea than in a Backroads biking trip.

by Julie Schauer | Jul 26, 2013 | Contemporary Art, Eco-Art, Environmental Art, Greater Reston Arts Center, Local Artists and Community Shows, Painting Techniques, Sculpture

|

| William Alburger, Forest, 2013, 65″ x 108″ x 9″ rescued spalted birch, in an solo exhibition at GRACE |

Eco-friendly art is meeting the world of high art, if we’re to take a cue from what’s showing at local art centers and galleries. It can be stated that the earliest environmental art started with the artists’ visions and applied those visions to the environment, with little interest in sustainability.

Quite the opposite trend is developing now. Several emerging artists, the “environmental artists” of the 21

st century put nature in the center–not the artist or the idea. Nature is the subject and the artist is nature’s follower. The following artists’ creations are about the land and earth; other artists interested in the environment have been more concerned with a world under

the sea.

|

William Alburger, Non-traditional Backwards

One-Door, 2012, 27″ x. 13.5″ x 5.25

reclaimed Pennsylvania barn wood, specialty

glass and fabric |

William Alburger lives in rural Pennsylvania, where he picks up scraps of wood from fallen trees and mixes them with discarded barn doors. He is a passionate conservationist with an addiction to collecting what otherwise would be burned, decayed or discarded in landfills. Largely self-taught, Alburger formerly worked as a painting contractor. His art is both pictorial and practical. Some sculptures almost look like two-dimensional works, while others function as shelves or furniture. Hidden doors, cubbyholes and cabinets create surprises, making the natural world his starting point for expression. Intrusions of man-made items are minor. The knots, whirls, colors and textures of wood speak for themselves, revealing rustic beauty.

|

William Alburger, Synapse, 2013,

65″ x 23″ x 5.25″ rescued spalted

poplar and Pennsylvania barn wood |

Currently the Greater Reston Area Arts Center (GRACE) is hosting a solo exhibition of Alburger’s works. In Synapse, Alburger cut into the interesting grain and patterns of fallen poplar. He framed top and bottom with old barn wood and reconfigured the form to suggest the space where two forms meet and form connection. Allburger finds what is already there in nature, but, through presentation, teaches us how to see it in a new way. Otherwise, we might not notice what nature can evoke and teach us.

|

Pam Rogers, Tertiary Education, 2012, handmade

soil, mineral and plant pigments, ink, watercolor

and graphite on paper. Courtesy Greater

Reston Area Art Association |

Dedication to the natural world is second nature to Pam Rogers, whose day job is as an illustrator in the Natural History Museum of the Smithsonian Institution. “I’m inclined to see environment as shaping all of us,” Rogers explains, noting the importance of where we come from, and how our natural surroundings mark our stories and connections. While drawing natural specimens, she sees as much beauty in decay is as in birth, growth and development. We’re reminded that everything that comes alive, by nature or made by man, will turn to dust. Rogers’ drawings combine plants, animals and occasional pieces of hardware. Some of the pigments spring from nature, the red soil of North Georgia and plant pigments.

As in Alburger’s Synapse, above, Rogers seeks to form connections between man and the environment. She inserts nails and other links into the drawings from nature for this purpose, as in Stolen Mythology, below. At the moment, Pam Rogers’ art is in the show, {Agri Interior} in the Wyatt Gallery at the Arlington Arts Center. One of her paintings is now in a group exhibition, Strictly Painting, at McLean Project for the Arts.

|

Pam Rogers, Stolen Mythology, 2009 mixed media

|

Rogers mixes traditional art techniques with abstraction, natural with man-made, sticks and strings, and does both delicate two-dimensional works and vigorous three-dimensional art. Her sculptures and installations explore some of the same themes. At the end of last year, she had an exhibition at GRACE called Cairns. Cairns refer to a Gaelic term to describe a man-made pile of stones that function as markers. Her work, whether two-dimensional or three-dimensional, is also about the markers signifying the connections in her journey.

|

| Pam Rogers, SCAD Installation (detail), plants, wire, metal fabric, 2009 |

“There are landmarks and guides that permeate my continuing journey and my exploration of the relationship between people, plants and place. I continually try to weave the strings of agriculture, myth and magic, healing and hurting.” Several of her paintings have titles referring to myths, including Stolen Mythology, above, and another one called Potomac Myths. Originally from Colorado, Rogers also lived in Massachusetts and studied in Savannah for her Masters in Fine Art. It’s not surprising that, in college, she had a double major in Anthropology and Art History.

|

Henrique Oliveira, Bololô, Wood, hardware, pigment

Site-specific installation, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution

Photograph by Franko Khoury, National Museum of African Art |

Artists cite the spiritual and mythic connection we have to environment. As a student, Brazilian artist Henrique Oliveira noted the beauty of wood fences which screened construction sites in São Paolo. Observing these strips being taken down, he collected them and re-used the weathered, deteriorating sheets of woods for some of his most interesting sculpture. Oliveira was asked to do an installation in dialogue with Sandile Zulu for the Museum of African Art in Washington, DC. His project, Bololô, refers to a Brazilian term for life’s twists and tangles, bololô. The weathered strips can act like strokes of the paint brush, with organic and painterly expression, reaching from ceiling to wall and around a pole but usually not touching the ground. Oliveira’s installation is a reflection of the difficulty in staying grounded in life, in this tangle of confusion.

|

Danielle Riede, Tropical Ring, 2012, temporary installation in the Museum of Merida, Mexico

photo courtesy of artist |

|

|

Environmental concerns played a part in the collaboration of Colombian artist Alberto Baraya and Danielle Riede, at the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art, shown in 2011. Expedition Bogotá-Indianapolis was “an examination of the aesthetics of place and its plants” in central Indiana. For two years, the artists collected artificial plants from second-hand stores, yard sales and neighborhoods in around Indianapolis. Last year Riede did an installation for the City Museum of Merida, Mexico, Tropical Ring. It’s made of artificial plants garnered from second-hand crafts in from Indiana and Mexico. The plants were cut and reconfigured to evoke the pattern of an ecosystem, indoors. Currently, the artist is looking for a community partner to participate in Sustainable Growths, an art installation of crafts and other re-used objects destined for abandoned homes in Indianapolis.

|

Danielle Riede, My Favorite Colors, 2006, photo courtesy

http://www.jardin-eco-culture.com/

|

|

|

|

Originally, Riede’s primary medium was discarded paint, which she gathered from the unused waste of other artists or the pealing pigments of dilapidated structures. My Favorite Colors, right, follows several paths of recycled paint along the wall of the Regional Museum of Contemporary art Serignan, France. Beauty comes from the color, light, pattern, and even from the shadows cast on walls to deliberate effect. The memory landscape is uniquely described in the eco-jardin-culture website. The installation is permanent, although much of what we consider environmental art is temporary.

|

Sustainable Growths: Painting with Recycled Materials is Riede’s

project to bring meaning to abandoned homes in Indianapolis. Artist’s photo |

Fallen trees, branches and other wastes of nature are tools of drawing to artist R L Croft. Some artists feel they have no choice but to re-use and re-claim discarded goods or fallen debris, as many folk artists and untrained artists have always been doing. The need to draw or create is innate and a constant in one’s identity as an artist, but it’s not easy to get commissions, jobs or sell art. Art materials are very expensive, so there is a practical objective to using environmental objects which do not need to be stored.

|

| R L Croft, Portal, 2011, Oregon Inlet, North Carolina |

To Croft, using the environment is a means of drawing, but on a very large scale. His outdoor, impromptu drawings-in-the-wild are images grounded in his style of painting and sculpture. Croft has made a number of sculptures called “portals” and/or “fences,” most of which have been carried away by rising tides or decay. He makes these assemblages out of debris found along the beaches, particularly those of the Outer Banks, in North Carolina. Portal at Oregon Inlet, NC, left, was constructed of found lumber, nails, driftwood, plastic, rope, bottles, netting, etc.

Environmentalism is not the primary content of his art. Croft says: “Making art for the purpose of being an environmentalist doesn’t interest me. Making art whose process is environmentally friendly does interest me.” He works in rivers, woods and on beaches. In the aftermath of one natural disaster, Hurricane Irene, he brought meaning to the incident–both personal and anthropological.

.jpg) |

R.L. Croft, Shipwreck Irene, in Rocky Mount, N.C. Built in October, 2012, it’s still there but

less recognizable as a ship form. The location is in Battle Park

off of Falls Road near the Route 64 overpass. Photo courtesy of artist.

|

Croft made Shipwreck Irene in Rocky Mountain, NC, when the Maria V. Howard Art Center held a sculpture competition and allowed him the use of fallen debris after Hurricane Irene, which left as much physical devastation as his sculptures allude to metaphorically. The shipwreck is a very old icon in the history of art, usually associated with 17th century Dutch seascapes. But to Croft, who in childhood found healing in the Outer Banks after the death of his mother, the meaning is deep. The area known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic” fed his early sense of adventure and aesthetic appreciation for texture, decay and the abrasive effects of wind, sand and water.

Hurricane Irene “is much like the resilient community frequently raked over by severe hurricanes, yet plunging forward. The current art center is world class and it is the replacement for an earlier one destroyed when still new. ” Croft said. Shipwreck Irene is still there, but decay renders it increasingly unrecognizable as a ship form. The temporary aspect is expected. “People of the region know grit and impermanence,” the artist explained. “I’m told that Shipwreck Irene became a habitat for small animals and small birds but that is a happy accident.”

|

| R L Croft, Sower, 2013, 22 x 14 courtesy artist |

|

Croft has also said: “Nothing can be taken for granted. Constant change proves to be the only reliable point of reference. Equilibrium being as fleeting as life itself, one fuses an array of thought fragments retrieved from memories into a drawing of graphite, metal or wood. By doing so, the artist builds a fragile mental world of metaphor that lends meaning to his largely unnoticed visit among the general population.” Croft did an installation in the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, a drawing in the wild entitled Sower, in homage to Van Gogh He worked in wattle to make a large drawing that, in a metaphorical, abstracted way, resembles a striding farmer sowing his seed. The farmer is the winged maple seed and it references Vincent’s wonderful ink line drawings.

Nature has been the subject of art by definition and a curiosity about the natural world has defined a majority of artists since the Renaissance. The first wave of Environmental Artists applied their vision to the environment by directly making changes to the environment–permanent (Robert Smithson, James Turrell) or temporary (Christo and Jeanne-Claude) Turrell ,whose most famous work is the Roden Crator in Arizona, is the subject of a major

retrospective now in New York, at the Guggenheim.

It is one thing for art to alter the environment, as the earliest environmental artists did. It is another thing to make art to call attention to the problems of waste and depletion of the earth’s resources. Yet, it’s an even stronger statement when professional artists exclusively make art that re-uses discarded items and turns them into art. Environmental Art today addresses waste reduction and stands up against the problems caused by environmental damage to our rapidly changing world. Designers are getting into this process, as explained in the previous blog. For example, Nani Marquina and Ariadna Miguel design and sell a rug made of discarded bicycle tubes, Bicicleta.

In the future, I hope to blog on how artists address sustainable agriculture. Currently, the main exhibition at Arlington Arts Center, Green Acres: Artists Farming Fields, Greenhouses and Abandoned Lots.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by admin | Jun 17, 2013 | Architecture, Cité Radieuse, Cities, Emmanuel Barrois, FRAC, Glass, Kenzo Kuma, Le Corbusier, MuCEM, Rudy Ricciotti, Stefano Boeri, Villa Méditerannée

|

| Villa Méditerrannée, a new building by Stefano Boeri, has an auditorium below the sea, but much if its exhibition space is suspended in mid-air. This view leads to the towers of Marseille’s 19th century multi-colored marble cathedral. |

France’s oldest city and one the great ports of the Mediterranean has been revitalized to become a European Cultural Capital of Europe this year. Some of the most innovative practicing architects of today are making their mark on the city, cleaning up old areas and transforming it into an exciting new seaport environment. Abandoned parts of the old port and places where immigrants first entered the city are in the process of being turned into new commercial areas, with restaurants, art galleries, museums, music venues and shops.

|

Marseille became a Greek city about 2700 years ago. The

island is where the Count of Monte Cristo was imprisoned. |

Sheaths of glass, concrete and metal, the materials of new architecture, butt up against the old stone towers, hills and masts of this port which geographically reminds me of San Francisco to a certain extent. (Reminiscent of the Alcatraz, there’s an island in the harbor containing Chateau d’If, where the Count of Monte Cristo was imprisoned.) Yet, the feeling inside is more rugged and grittier than San Francisco, with a multinational flavor.

|

Ricciotti designed MuCEM with

a ramp linked to Fort Saint-Jean |

My photos taken last month showed the MuCEM (Museum of Civilizations of Europe and the Mediterranean) nearly finished, adjacent to the Villa Méditerranée. The 236 square foot box building, right, will be the country’s largest museum outside of Paris. In essence, the building has two facades, the glass covering and the concrete covering. The outer covering is a dark blue concrete which I actually thought was made of steel/ it shields the glass and museum visitors from the intense Mediterranean sun. The “lacey” outer face and “glassy” inner building and the two parts connect with a ramp. A walkway also links the new building to the very old 12th century building and tower, the Fort Saint-Jean.

|

| From another vantage point (Parc du Pharo), the 19th century multi-colored marble cathedral pops up behind the t concrete lattice patterns of the brand new Museum of Mediterranean Civilizations (MuCEM). |

Architect Rudy Ricciotti’s style has also raised eyebrows. He designed a floating gold roof on the Louvre in Paris to house the Islamic collection and a Jacques Cocteau museum in Menton. Each building is quite different, though, unlike Frank Gehry’s architecture. MuCEM’s concrete shell resembles a fisherman’s net. Its concrete is blue-gray, but that color will change with reflections of light, water and the sun. Ricciotti calls the eight different lattice patterns “sun-breakers.” They are meant to shield the southern and western facade from intense sunlight. MuCEM opened June 7, 2013.

|

A fishnet pattern of concrete

shields MuCEM from intense

sun on the south and west. |

Next door is the Villa Méditerrannée, a product of Italian architect Stefano Boeri’s design studio, and a building devoted to exhibiting Marseille’s Mediterranean culture. It has a huge, cantilevered roof, but below it is an area with a view into the sea basin. The building’s auditorium goes under the water, too. The museum officially opened last weekend. Its exhibitions and films visualize the present and the future of the sea. Supported by the region of Provence-Alpes-Cote’Azur, Villa Méditerannée hopes to encourage communication among the many countries which have ports on the Mediterranean It can be understood as an exciting new cultural center for the entire Mediterranean region.

|

Another view of Boeri’s Villa Méditerannée, with Ricciotti’s MuCEM and Fort Saint-Jean to right. Glass is used extensively in the new buildings to take

advantage of reflections of sun and water. |

There are other new museums, including the Musée des regards de Provence, where the old health station had been and where immigrants first went as they entered Marseille. The museum has a Michelin three-star restaurant.

There’s a new museum of decorative arts and a fine arts museum at Palais Longchamp has reopened after being closed many years. (That museum and the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence are hosting large exhibitions of the shares a major exhibitions of the many important artists who painted in the region, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Matisse, etc. In fact, Arles and other venues in Provence are sharing in the European Cultural Capital events. The Palais du Pharo, on the shoreline of Marseille has a large sculptural exhibition of steel arcs by Berner Venet, in celebration of the events.)

|

In the Parc du Pharo, the sculptor Bernar Vernet designed 12 steel arcs, called

Desordre, created a pattern of light and shadow against the shoreline. |

|

Reflective glass creates is s museum without walls,

at FRAC, a regional museum of contemporary art. |

It seems that all the contemporary architects working here–the local and the international ones–respect the city’s very irregular seaport. They design with the knowledge that water reflects light and that glass reflects water and light. Multitudes of glass heighten the reflections many times over.

FRAC (Fonds regional d’art contemporain or the Regional Collection of Contemporary Art) opened in March, 2013. The building has about 55,000 square feet. Its the work work of Japanese architect Kenzo Kuma. The exterior is covered with 1,500 panes of glass, all of which have been recycled and enameled in the workshop of Emmanuel Barrois.

|

Kenzo Kuma designed FRAC, a regional museum of

contemporary art |

Kuma, like Ricciotti, is concerned with shielding the sun. (It’s interesting that exhibition while I was there concerned environmental art.) The glass is hung and diverse angles, offset from the building at various places. Kuma tries to evoke a museum without walls, and a feeling of openness prevails. There is a beautiful, peaceful aura to his building, a feeling modern Japanese architects convey so well. Kuma also said that he imitated the flow of space learned from the study of Le Corbusier, a labyrinthine, interlocking flow of space.

|

| Le Corbusier, Cité Radieuse, 1947-52. It has 347 apartments on 12 stories |

Going to Marseille warrants a trip to the Cité Radieuse, Le Corbusier’s masterpiece of modern architecture, formerly called l’Unité d’Habitation.

|

Entrance to Le Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse

The ground floor rests on muscular “pilotis” made

of concrete, which hold up the building |

His blueprint for modern living, completed in the 1950s, unifies all aspects of living, eating, school, doctors and recreation in one building. Unfortunately, there was a fire last year which harmed some units but most of the building is intact. Many portions of the building have recently been painted and the colors make a brilliant splash reminiscent of Mondrian. It’s hard to go to the restaurant without disturbing clients or to visit one of the individual apartments without an invitation.

|

| The ground floor lobby radiates warmth and color |

As much as I don’t necessarily think architects should try to be sociologists who tell people how to live, but this building succeeded and the residents like it. The concept and design were repeated again in Nantes, Berlin, Briey and Firminy. Le Corbusier proved that the modern concrete could be beautiful, colorful and expressive. Concrete, usually when reinforced with cast iron, need not be sterile.

|

An art school is on the rooftop. The

force of brutal concrete pushes

against the sky |

The day we were there, a film crew was making a television commercial on the roof and all kinds of goods were set blocked off and set aside for film use. It was May 22nd, and the sky was making some interesting cloud designs. Like Antoni Gaudí, Le Corbusier made his ventilation shafts into expressive, sculptural forms. The brutal, rough-hewn concrete has force and muscle which come alive against the muscle a alive against the sky.

The rooftop is a communal terrace and residents have a straight view to Marseille and the Mediterranean Sea. We’re left with the feeling that yes, Marseille is a city with muscle and it will be a force for 2700 more years.

|

Notre-Dame de la Garde, perched high above

the old port, has protected the

boats for years |

Construction was going on everywhere the other time I went to Marseille, in 2011. The photo below on the left, taken at that time, may represent a vista that’s gone now. It was on the other side of the port and opposite the church of Notre-Dame de la Garde.

|

Fishing and seafaring have always

been the business of Marseille. |

Boats, fishing and seafaring will continue for a long time, as long as we respect and protect our resources.

by Julie Schauer | May 13, 2013 | Eco-Art, Industrial Design, Local Artists and Community Shows

|

| Various artists designed soundproof wall panels in The Next Wave, 21st century design show |

Congratulations to the Artisphere in Arlington, Va. for showcasing the latest in contemporary industrial design. The Next Wave: Industrial Design Innovation in the 21st Century is an exhibition curated by Douglas Burton of Apartment Zero. It’s a kaleidoscope of many different designers from around the world, brought together in a pleasing, well-integrated exhibition.

|

| Stacking Drawers by Yael Mer and Shay Alkalay, Israel |

The objects and furniture taken together become a peaceful setting to make us dream and think about where and how good design and convenient living can come together. Sleek black and white are mixed with a selection of greens, reds and yellows. This exhibition’s design is superb; it’s a treat for the eyes. Considering that these designers did not plan their pieces to be shown with other designers, this installation is one that shows well as an ensemble.

Most objects were functional, but the only “machine” to catch my eye was a vacuum cleaner. My photos show some objects, but there was also a selection of light fixtures which didn’t make the pictures.

According the Burton, the curator: “Industrial design is the creation and development of concepts that optimize the function, value and appearance of products for our mutual benefit.” Since the Bauhaus was founded in Germany in the early 20th century, the marriage of form and function in industrial design has been strong. At times, architects have enjoyed playing the role of sociologist and have gotten into the process, too. Good industrial design propelled Apple Computer to great success, because its founder, Steve Jobs, was obsessive about good design. It paid off!

|

| Bodo Sperlein of Germany designed the Re-Cyclos Equus Set, while Lladro of Spain made it. |

The cleverness of designers always intrigues me, and ingenious ideas abound in this show. Josh Owens’ SOS Stool doubles a stool with cup holders, or as a table (photo on bottom). The Re-Cyclos Equus Set (above) features teapots and cups composed of horses’ heads and legs. It puts an ultra modern spin on an age-old practice in furniture design, reminding me how the ancient Egyptians uses lions’ claws for the feet of their chairs.

|

| Happy Family by Beau Oyler, Jared Aller |

Admittedly, I like all of these designs but am slow to buy it and live with it. It is so clean, so perfect and how many of us actually live so orderly? Most of these designs are a great look for urban apartment living. Even if I wouldn’t necessarily buy the products, it’s inspiring to think about good design and restful to ponder the results. As Burton asserts at the entrance to the exhibit: “It is innovation in design that allows us to experience moments of engagement and inquiry.”

There are several examples of fiber arts. Many of the designers work with recycled materials. One of the most interesting was a rug made out of the inner tubes of used bicycles. Mani Marquina and Ariadna Miguel of Spain designed Bicicleta Rug. Made of rubber, it’s easy on the feet. I’d like to have it on my kitchen floor to cushion my feet while cooking. If I need more shelf space, or a places to put utensils, books and plants, Happy Family (shown above right) is a modular hanging shelf made of recyclable polypropene and connected with magnets. When there is company, Kaleido-Trays (below) is colorful and makes for easy storage.

|

| Clara Von Zeigbergk of Denmark designed Kaleido Trays, while Thomas Shiner designed Seminar Bench |

|

| A mix of accessories by various designers |

Arlington is to be congratulated and thanked for its commitment to supporting the arts, with its numerous theaters, gallery spaces for emerging artists and for educational outreach. The Artisphere Yarn Bomb is up now, too, carving a trail for pedestrians to follow with its vivid colors. Just across the Potomac from Washington, DC, Arlington’s art scene, along with the Torpedo Factory in Alexandria, add to the rich art scene that’s already in DC.

The exhibition closes on Sunday, May 19th. It has already been up around 3 months, so I thank designer friend Amanpreet Birgisson for telling me about it. For more information contact: [email protected] or www.apartmentzero.com.

|

| Josh Owen designed the SOS stools; behind is the Passion Chair by Philippe Starcke |

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 22, 2013 | Art and Literature, Art Appreciation: Visual Analysis, Baroque Art, Diego Velázquez, Fiber Arts, Mythology, Painting Techniques

|

Diego Velázquez, Las Hilanderas (The Spinners), oil on canvas, H: 220 cm (86.6 in) x W: 289 cm (113.8 in)

The Prado, Madrid |

(Not for beginning art students; I was not able to understand or interpret this painting at all until teaching a class in Mythology.)

The study of myths in all cultures, like the study of art, may seem obscure but it can illuminate some truths about humanity. Around the world, the beauty of weaving has some association with magic. So we look to Diego Velázquez’s Las Hilanderas (also called The Spinners, The Tapestry Weavers or The Fable of Arachne) which focuses on the weaving contest between Pallas Minerva and Arachne described in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The foreground scene is about a competition which includes spinning and carding, preparations that come before the weaving of tapestries. The final outcome of the story is implied, not shown. Velázquez used a complex composition of diagonals to weave a tale, a fable that lovers of Charlotte’s Web should appreciate.

Velázquez often put humor into his mythological scenes, but The Spinners is not a satire. It’s related in theme to Las Meninas (The Maids of Honor), considered by a majority of art experts to be the greatest secular painting of all time. The painterly effects of hair and material which dazzle us in Las Meninas go even further in The Spinners, which has a similarly complicated meaning. Its format is horizontal rather than vertical, but it also features a foreground and background for two tiers of storytelling connected by an opening of light and stairs. As Las Meninas is a group portrait disguised as everyday life in Velázquez El Escorial Palace studio, Las Hilanderas is a narrative posed as a genre scene in the dress styles or 17th century Spain. It’s dated one year after Las Meninas, 1657.

|

| Detail of Pallas Athena (Minerva) and a “spinning” wheel |

According to Ovid, Arachne was a girl born to humble parents in Lydia (an area of Turkey famous for beautiful weavings). She was reknown for her remarkable skill, but did not see her art as a gift from the goddess of weaving. Arachne accepted praise that set her above Pallas Minerva (Pallas Athena–also the goddess of wisdom) in the art of weaving. She said, “Let her compete with me, and if she wins I’ll pay whatever penalty.” So Pallas Athena disguised herself as an old crone, saying “Old age is not to be despised for with it wisdom comes…..seek all the fame you wish as best of mortal weavers, but admit the goddess as your superior in skill.”

Arachne wasn’t humbled and said “Why won’t (the goddess) come to challenge me herself?” Athena then cast off old age and revealed herself. Arachne was not scared and immediately took up the challenge of the competition. In foreground of Velázquez’s canvas, Athena (in a headscarf) and Arachne set up their spinning and carding operations in preparation for the weaving competition. At least three assistants are helping in the task. There are balls and balls of wool and thread and even a cat, but no looms in sight.

Just as Shakespeare liked to insert plays within his plays to elucidate the story, Velázquez was fond of putting subsidiary stories in his paintings. Another episode takes place in the background, although Velázquez skipped parts and hinted of the conclusion under the archway. Here Athena wears her goddess of war helmut. There are the same number of people in front as in back, five. It would be reasonable to believe that the young women in the back are the same assistants who help in the foreground, but have changed their clothing into fancy dresses. Only the lowly-born Arachne, furthest from the viewer, is modestly dressed.

|

From the girl “Fate” in shadow, we peer into a scene where Athena is about to strike Arachne.

Arachne’s belly is the center of the painting, hinting of the spider’s belly she will become. |

According to Ovid’s tale, when goddess and girl had completed their tasks, Athena revealed her tapestry with its central subject of Athena winning her competition with Poseidon to be the patron of Athens. She wove an olive vine from her sacred tree into the tapestry’s border. Secondary scenes showed the power of gods and goddesses as they triumphed over humans. The subject of Arachne’s tapestry was stories of trickeries by gods and goddesses, at the expense of mortals. She had shown as her central subject as the rape of Europa by Zeus in the form of a bull. This scene is recognized in the back of this painting as a replica of Titian’s famous painting of that subject in the Spanish royal collection.

“Bitterly resenting her rival’s success, the goddess warrior ripped it, with its convincing evidence of celestial misconduct, all asunder; and with her shuttle of Cytorian boxwood, struck at Arachne’s face repeatedly.” In the painting, Athena holds her shuttle in the foreground, not the background, but Velázquez cleverly placed it in Athena’s left hand where it points to the next image of Athena in armor. Velázquez highlighted the goddess’s anger against a light blue background and emphasized the force of Athena’s striking arm. Arachne’s head is nearly the center of the painting, but the viewer realizes she will exist no longer. “She could not bear this, the ill-omened girl, and bravely fixed a noose around her throat: while she was hanging, Pallas, stirred to mercy, lifted her up and said:

“Bitterly resenting her rival’s success, the goddess warrior ripped it, with its convincing evidence of celestial misconduct, all asunder; and with her shuttle of Cytorian boxwood, struck at Arachne’s face repeatedly.” In the painting, Athena holds her shuttle in the foreground, not the background, but Velázquez cleverly placed it in Athena’s left hand where it points to the next image of Athena in armor. Velázquez highlighted the goddess’s anger against a light blue background and emphasized the force of Athena’s striking arm. Arachne’s head is nearly the center of the painting, but the viewer realizes she will exist no longer. “She could not bear this, the ill-omened girl, and bravely fixed a noose around her throat: while she was hanging, Pallas, stirred to mercy, lifted her up and said:

“Though you will hang, you must indeed live on, you wicked child; so that your future will be no less fearful than your present is, may the same punishment remain in place for you and yours forever!” Then, as the goddess turned to go, she sprinkled Arachne with the juice of Hecate’s herb, and at the touch of that grim preparation, she lost her hair, then lost her nose and ears; her head got smaller and her body, too; her slender fingers were now legs that dangled close to her sides; now she was very small, but what remained of her turned into belly, from which she now continually spins a thread, and as a spider, carries on the art of weaving as she used to do.” Note that the belly of Arachne which will be the spider’s core is at the exact center of the painting.

|

| The Spinners, right side, detail of Arachne |

With the fable explaining the origin of spiders, it makes sense that the preparatory activity in the foreground is all about the thread (and the spinning of fate), because there is so much winding to that thread. I interpret the young helpers to Arachne and Pallas Athena as the three Fates. The Fates can be described as Moira in singular name, or Moirai. Their specific names are Clotho meaning “Spinner,” Lachesis, who measures the thread, and Atropos who is inflexible and cuts it off. The three Fates are goddesses and daughters of Zeus who are sometimes considered more important than Zeus in their ability to seal destiny. They come in various disguises, and wouldn’t be surprising if these young women seen as helpers are really the ones who ultimately are in charge. In myth and life, there is always the question of how much free will or how much fate determines outcome.

Velázquez uses highlights and shadows strategically for his story telling goals. Arachne stands out because she is highlighted to a much greater degree than Minerva is, yet we see nothing of her face. How ironic that he, Velázquez who proudly showed his face in Las Meninas, his allegory of painting, does not allow Arachne to show hers. Her back is to us, as she labors deftly and diligently. Both Athena and Arachne are barefoot. The goddess, who is older though not an old lady, even shows some leg!

One of the women in the background is looking back to the foreground, a complexity that pulls the composition together. Perhaps she had been the only one of three Fates who supported Arachne and was pulling strings for her. The woman or Fate dressed in blue shows her back to the viewer, but she appears again immediately below in the foreground, though separated by stairs. Here Velázquez has deliberately darkened her face in shadow, in deeper shadow than is necessary for the composition. As in other Velázquez paintings, shadowed figures can signify that a character in the painting is an actor, an actor who is playing a role in an act of deception. Though she aids Arachne in the guise of as a common peasant girl, her concern with thread could actually be in the process of spinning a different fate.

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, Pallas and Arachne, oil, 1634, at Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond |

Velazquez was familiar with the fable of Arachne from a Peter Paul Rubens painting of Pallas and Arachne which was owned by the Spanish royal family. The Rubens composition is more violent, with Pallas Athena striking Arachne to the ground. A copy of this painting was in the background of Las Meninas, Velázquez’s most famous painting of 1656, a composition which raises the status of art and the artist. Velázquez must have thought of the art of weaving as a noble pursuit, similar to the art of painting. Both require exceptional talent and skill. Weaving and spinning have additional, magical connotations in mythology, such as the woven clothing of goddesses, the weavings of Odysseus’ wife and the thread which let Theseus out of the labyrinth. Velázquez was a great artist, but, like the prodigy Arachne, he was not of noble birth.

|

Detail of self-portrait in Las Meninas, with

the red cross added later |

|

|

Las Meninas — which contains a portrait of the artist in the act of painting — is about the role of the artist, the origins of creativity and the attainment of status. The Spinners further explores these subjects and elucidates some of the same ideas. Our talents are divine gifts and, as mortals, there are limitations on us. No matter what the artist’s genius is, there are warnings against boasting. In the end, we are left with a reminder of the punishment which comes from carrying pride too far.

The paintings compare artistry and skill, and the status of the artist, to the non-negotiable status of higher beings, i.e., the Spanish Royal family, and an Olympian goddess. There is a crucial difference, however. Arachne, an upstart weaver, was just a girl when she challenged the goddesses of wisdom and weaving and the Fates. Velázquez, on the other hand, was 56 when he painted Las Meninas, and his self-portrait looks outward asserting the importance due to him. Remember how Athena in the guise of an old lady had warned Arachne that with old age comes wisdom.

|

Velázquez, The Water Seller of Seville, c. 1620

Apsley House, London |

Velázquez had also been an extraordinary prodigy, only about 20 when he painted The Water Seller of Seville. There, an elderly man is passing a glass of water to an adolescent boy while a young adult man stands behind. It was nearly 40 years later that he finally gained knighthood status, the Order of Santiago. A red cross, painted on his chest three years after completing Las Meninas, indicates that title he attained shortly before death in 1660. However, from Velázquez’s other paintings, we know he treated royalty and peasant with equal respect and dignity. The old man in The Water Seller of Seville wears a torn cloak indicating his humble means compared to the young boy he serves. So it is not Arachne’s lowly birth, but her youthful pride which denied the wisdom of age that Velázquez sees as her ultimate downfall. The attainment of greatness is possible if one waits, for only with age comes wisdom.

Velázquez’s stylistic change over the years from tight and controlled to very painterly is typical. He painted two allegories of deception, one mythological, when he was around 30 and in Rome, a turning point in his career. (You can some of the changes of his style from early to middle and late in a blog about him.)

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Apr 9, 2013 | 19th Century Art, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Drawings, Durer, Exhibition Reviews, Jean-Francois Millet, National Gallery of Art Washington, Pastels, Portraiture, Renaissance Art, Watercolor

|

Albrecht Dürer, The Head of Christ, 1506

brush and gray ink, gray wash, heightened with white on blue paper

overall: 27.3 x 21 cm (10 3/4 x 8 1/4 in.) overall (framed): 50 63.8 4.1 cm (19 11/16 25 1/8 1 5/8 in.)

Albertina, Vienna |

The National Gallery of Art is hosting the largest show of Albrecht Dürer drawings, prints and watercolors ever seen in North America, combining its own collection with that of the Albertina in Vienna, Austria. Across the street in the museum’s west wing is the another exhibition of works on paper, Color, Line and Light: French Drawings Watercolors and Pastels from Delacroix to Signac. The French drawings are spectacular, but it’s hard to imagine the 19th century masters without the earlier genius out of Germany, Dürer, who approached drawing with scientist’s curiosity for understanding nature.

|

Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait at Thirteen, 1484

silverpoint on prepared paper, 27.3 19.5 cm

(10 3/4 7 11/16 in.) (framed): 51.7 43.1 4.5 cm (20 3/8 16 15/16 1 3/4 in.)

Albertina, Vienna |

Dürer’s famous engravings are on view, including Adam and Eve, but with the added pleasure of seeing preparatory drawings and first trial proofs of the prints. Some of his most famous works such as the Great Piece of Turf and Praying Hands, are there also. In both exhibitions, as always, I’m drawn to the beauty and color of landscape art, especially prominent in the 19th century exhibition. However, both shows have phenomenal portraits to give us a glimpse into people of all ages with profound insights.

Dürer drew his own face while looking in the mirror at age 13, in 1484. He still had puffy cheeks and a baby face, but was certainly a prodigy. Like his father, he was trained in the goldsmith’s guild which gave him facility at describing the tiniest details with a very firm point. Seeing his picture next to the senior Dürer’s self-portrait, there’s no doubt his father was extremely gifted, too.

|

Albrecht Dürer, “Mein Agnes”, 1494

pen and black ink, 15.7 x 9.8 cm (6 1/8 x 3 7/8 in.)

(framed): 44.3 x 37.9 x 4.2 cm (17 3/8 x 14 7/8 x 1 5/8 in.)

Albertina, Vienna |

In his native Nuremburg, the younger Dürer was recognized at an early age and his reputation spread, particularly as the world of printing was spreading throughout the German territories, France and Italy. We can trace his development as he went to Italy in 1494-96, and then again in 1500, meeting with North Italian artists Andrea Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini and exchanging artistic ideas. Dürer is credited with bridging the gap between the Northern and Italian Renaissance. I personally find all his drawings and prints more satisfying then his oil paintings, because at heart he was first and foremost a draftsman.

Though we normally think of Dürer as a controlled draftsman, there are some very fresh, loose drawings. An image he did of his wife, Agnes, in 1494, shows a wonderful freedom of expression, and affection. He married Agnes Fry in 1494 and did drawings of her which became studies for later works. She was the model for St. Ann in a late painting of 1516 and the preparatory drawing with its amazing chiaroscuro is in the exhibition.

|

Albrecht Dürer, Agnes Dürer as Saint Ann, 1519

brush and gray, black, and white ink on grayish prepared paper; black background applied at a later date (?)

overall: 39.5 x 29.2 cm (15 1/2 x 11 1/2 in.) overall (framed): 64 x 53.4 x 4.4 cm (25 1/4 x 21 x 1 3/4 in.)

Albertina, Vienna |

|

Also on view are Durer’s investigations into human proportion, landscapes and drawings he did of diverse subjects from which he later used in his iconic engravings. We can trace how the drawings inspired his visual imagery. There are also several preparatory drawings of old men who were used as the models for apostles in a painted altarpiece.

|

Albrecht Dürer, An Elderly Man of Ninety-Three Years, 1521

brush and black and gray ink, heightened with white, on gray-violet prepared paper

overall: 41.5 28.2 cm (16 5/16 11 1/8 in.) overall (framed): 63.6 49.7 4.6 cm (25 1/16 19 9/16 1 13/16 in.)

Albertina, Vienna |

My favorite drawing of old age, however, is a study of an old man at age 93 who was alert and in good health (amazing as the life expectancy in 1500 was not what is today.) He appears very thoughtful, pensive and wise. The softness of his beard is incredible. The drawing is in silverpoint on blue gray paper which makes the figure appear very three-dimensional. To add force to the light and shadows, Durer added white to highlight, making the man so lifelike and realistic.

|

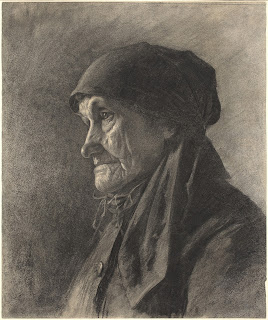

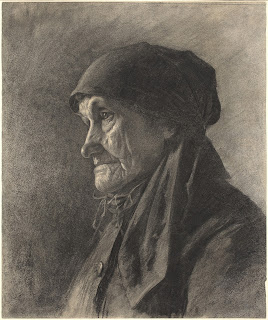

Léon Augustin Lhermitte, An Elderly Peasant Woman, c. 1878

charcoal, overall: 47.5 x 39.6 cm (18 11/16 x 15 9/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James T. Dyke, 1996 |

In the other exhibition, there’s a comparable drawing by Leon Lhermitte of an old woman in Color, Line and Light. Lhermitte was French painter of the Realist school. He is not widely recognized today, but there were so many extraordinary artists in the mid-19th century. What I find especially moving about the painters of this time is more than their understanding of light and color. I like their approach to treating humble people, often the peasants, with extraordinary dignity. Lhermitte’s woman of age has lived a hard and rugged life and he crinkled skin signifies her amazing endurance. We see the beauty of her humanity and the artist’s reverence for every crevice in her weather-beaten skin.

|

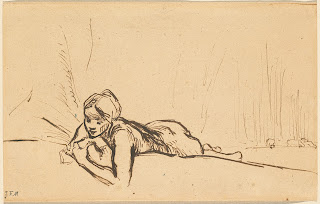

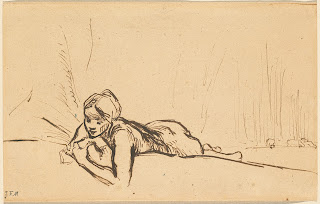

Jean-François Millet

Nude Reclining in a Landscape, 1844/1845

pen and brown ink, 16.5 x 25.6 cm (6 1/2 x 10 1/16 in.)

Dyke Collection |

|

There are many portraits of youth in the French exhibition, too, including fresh pen and inks such as Edouard Manet’s Boy with a Dog and Francois Millet’s Nude Reclining in Landscape, who really does not look nude.

Camille Pissarro’s The Pumpkin Seller is a charcoal without a lot of detail. She has broad features, plain clothes and a bandana around the head. She’s a simpleton, drawn and characterized with a minimum of lines but Pissarro sees her a substantial girl of character. The drawing reminds me of Pissarro himself. He may not be as well-known and appreciated as Monet, Renoir, Degas, yet he was the diehard artist. He was the one who never gave up, who encouraged all his colleagues and was quite willing to endure poverty and deprivation for the goals of his art. Berthe Morisot‘s watercolor of Julie Manet in a Canopied Cradle has a minimum of detail but is a quick expression of her daughter’s infancy.

|

Camille Pissarro, The Pumpkin Seller, c.1888

charcoal, overall: 64.5 x 47.8 cm (25 3/8 x 18 13/16 in.)

Dyke Collection |

Taking in all the portraits of both exhibitions, I’m left with thoughts of awe for beauty of both nature and humanity. The friends I was with actually preferred the French exhibition to the Dürer. There were surprising revelations of skill by little known artists like Paul Huet, Francois-Auguste Ravier and Charles Angrand. The landscapes by artists of the Barbizon School and the Neo-Impressionists, are important and beautiful, but perhaps not recognized as much as they should be. In both exhibitions, we must admire how works on paper form the blueprint for larger ideas explored in oil paintings.

|

Berthe Morisot, Julie Manet in a Canopied Cradle, 1879

watercolor and gouache, 18 x 18 cm (7 1/16 x 7 1/16 in.)

Dyke Collection |

It was a curator a the Albertina who wisely connected a mysterious Martin Schongauer drawing of the 1470s owned by the Getty to a Durer Altarpiece. The Albertina is a museum in Vienna known for works on paper, much its collection descended from the Holy Roman Emperors, one of whom Dürer worked for late in his career. The French drawings come from a collection of Helen Porter and James T Dyke and some of it have been gifted to the National Gallery. They’re on view until May 26, 2013 and Albrecht Dürer: Master Drawings, Prints and Watercolors from the Albertina will stay on view until June 9, 2013.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Mar 18, 2013 | 19th Century Art, Art Appreciation: Visual Analysis, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Landscape Painting, Monet, Musee d'Orsay, The Art Institute of Chicago

|

| Claude Monet, The Road to Giverny in Winter, sold last year, but hadn’t been seen in public since 1930 |

When Monet’s The Road to Giverny in Winter came up at auction about a year ago, it was the first time this idyllic painting had been on the art market since 1924. The painting leaves me with a magical impression, in the way Monet painted a pink sunset with warm highlights poking through the winter chill. Leave it Monet to see the beautiful warmth in the coldness of winter. So I wanted to explore his other paintings of snow and see how he developed the theme. At one point in the late 1870s, Monet’s colleague Manet tried to paint a scene of snow, but gave up, exclaiming that no one could do it like Monet.

When looking at reproductions online, we get a great variety of versions of the colors in the various photos of the same painting. No reproduction can substitute for seeing the actual painting. Monet did about 140 paintings of snow, but they represent just a fraction of his work. It’s snowing this morning March 18 and, looking out the window, I see only white, gray and brown with touches of forest green in the grass and pines. But I try to imagine how Monet would have seen it and the answer is that would depend on where he was in his long career.

The Road to Giverny in Winter is from Monet’s mid-career, before the extreme abstraction of his late style, but with the abundance of color characteristic of the fully developed Impressionism. There are several contrasting textures and the blurriness in the foreground indicates an icy wind. Some very dark blues and purples represent tree trunks and limbs, serving to anchor the painting’s composition. If Monet had a unifying color in The Road to Giverney in Winter, I’d guess that it had been blue. There are gray blues, powder blues and green blues. His blue is mostly a soft blue, but it is so well modulated with the pink, the green, the purple, rusty red and yellow.

|

| The detail from the center of The Road to Giverny in winter shows Monet’s array of colors |

The center is yellow, though. That’s the beginning of Giverny, the village he lived in from 1878 until his death in 1923. It’s where he created the ponds and nurtured the lily pads which gave rise to his most famous paintings. He placed this village in the center of the painting and painted its buildings yellow, appropriate because Giverny was a place of warmth where he found his center, his life. Warm yellow ochre meets its match in the yellows of the sky. There, it takes on radiance, brightness and a hint of green. The touch of green in the sky balances a deep forest green along the road on the right.

Color and composition are wonderful, but the brushstrokes are another reason this painting is so successful. Through his textural strokes, he suggests the flow of light at the end of day, the directions of winds and the barrenness of winter trees. Yet the sky is very smooth and we can sense that our shoes or boots will sink if we walk on the ground.

|

| Claude Monet, The Magpie, 1868-1869 |

The Magpie, one of the most popular paintings in Paris’ Musée d’Orsay, is also one of his earliest snow paintings. From this work, we trace how much he changed as his Impressionist style developed. He painted The Magpie in 1868-1869, before the first Impressionist exhibition of 1873. The public was not used to white paintings and it was rejected by the Salon of 1869. The way Monet created the magpie as a focal point in the composition reveals his genius, leading our eye to the bird through contrast and through repeated lines of movement in the fence’s shadows. The brushwork is masterful, as he uses the brush to show light, shadow and what remains of snow on narrow branches of trees.

The Magpie is a masterpiece of Monet’s early style, more Realist than Impressionist. There’s a sharp differentiation between light and shadow, though the shadows are mainly blue and not gray. Dark footprints in the foreground add a bit of mystery, but more than anything make us think of the rawness of nature’s beauty with only a hint of human intervention. He is still using black which may have added just the right amount of contrast. If we could not see the energy of his brushstrokes, a viewer may think the painting’s quality so good that it could be a photograph. The whites are bright enough, though, that you’d almost want to wear sunglasses to look at the painting. The Magpie appears to work its special magic by depicting what may be the day after a night of snow.

|

| Monet, The Street at Argenteuil, Snow Effect, 1874 |

In contrast to the view of snow in sunlight, it’s snowing in The Street at Argenteuil, Snow Effect, painted about 5 years later. The snowflakes are big, perhaps Monet was inspired by Japanese artist Hokusai. The whites are still very bright, but the most of the painting is gray or taupe, with touches of deep green and deep purple to make up the dark colors. There is a feel of something magical to be walking in this snow, even if it is cold. There’s touches of blue in the sky and a forest green where grass or pine needles appear.

|

| Monet, Snow at Argenteuil, 1875. Argenteuil was particularly important to the development of Monet’s Impressionist style. The years 1875-79 included some cold, harsh winters. |

Snow at Argenteuil, 1875, could be the day after a snow. It was painted in the same village but perhaps a year later. Its also a logical progression of style.Value contrast diminishes, but Monet loves to create a sense of depth and he is truly a master of perspective space, as much as the master of reflecting color. Black is almost entirely eliminated but we only have a few strokes of colors in their dark values. The town, nature and people are alive with movement and they go about their business despite the overall chill in the air. The blue in the painting, and the red bricks that been dulled to a pink, let us know it’s cold outside.

By 1880, Monet’s paintings were gradually becoming more and more abstract. He was less concerned with structure, depth and perspective. The paintings become more and more about color, pattern, vibration. In the Floating Ice near Vertheuil, we see tons of blue: deep blues green-blues, purple-blues and powder blue for the sky. Nearly half the painting is a reflection of the water, something he take to full abstraction with his water lily paintings later. It’s not only about the weather and how light effects the color, but Monet was also very concerned with pattern. The brushstrokes look like dabs of paint, just quick impressions.

|

| Monet, Floating Ice Near Vetheuil, 1880 |

As time goes on, even his snow scenes begin to take on more colors. Fortunately, 19th century painters were allowed an expanded palette of colors, and, for the first time, they could buy their paints in tubes. In many paintings, snow and ice become less dominated by white and gray, and appear to be dusted with all the hues of the rainbow. Near Lavacourt and Vetheuil, he did many paintings of the break up of ice on the River Seine. In these paintings, snow and ice combine with water in Monet’s color analysis of the reflections as they hit the water.

|

| The Road to Giverny in Winter is chronologically between the ice series on the Seine and the Grainstacks series |

|

|

|

Monet’s Grainstacks series of about 25 paintings includes at several snow scenes which offer a good comparison if we see them as Monet intended, next to the other paintings in the series. The Art Institute of Chicago’s painting, Grainstacks, Snow Effects, Sunset, 1891 is an example. This painting, an explosion of color on form is viewed in the gallery with at least six other paintings from the series. Shadows are not painted black or gray, but only as cold colors. (Blue, green and purple are cold colors, yellow, orange and red are warm.) Complementary color contrast creates a sensation, with the warmest colors in the upper righthand corner.

|

| Monet, Grainstacks, Snow Effect, Sunset, 1891 |

Monet traveled to Norway in 1895 and painted landscapes in the palest of colors. From Sandviken, Village in the Snow, it’s apparent that Monet’s interest in spatial depth, so apparent in earlier paintings, is gone, and overlapping shapes are the only forms to give definition to space. He used the lightest of pastel tints to differentiate color in paintings flowing with the brightness of snow, or in the whiteness of paint. The reds of barns are very red, yet they are submerged in white. It does seem that snow is everywhere and this is truly a winter wonderland. The edges of the canvas look as if they could dissolve in continuity.

|

| Monet, Sandviken, Norway, Village in the Snow, 1895 |

If snow continually inspired Monet and if he pressed himself to paint it whenever possible, we must see his relationship of snow as being akin to his relationship with painting water. Snow, like water, was a vehicle for him to explore the wonders of refracting light and reflection, to scatter colors as they reflect off of each other while forming unexpected designs and patterns.

About 10 years ago I took a painting class. Using a photo of a snow scene from the Morton Arboretum, my teacher kept encouraging me to see the purple in the landscape. She said that every landscape has an underlying color that unifies it and in this one it’s purple. The snow is purple, the water is purple, the tree trunks are purple, she said, and suggested that I stop interpreting what I knew was there: grays, whites, browns and blacks. She was trying to help me see as the artist sees and to use my eye to see an Impressionist’s vision of the world. There also was a gorgeous sunset in the painting I was doing, but I certainly didn’t paint a glorious rainbow of color effects as Monet did. Check out more of his snow scenes on this website.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by Julie Schauer | Feb 22, 2013 | Art and Science, Encaustic, Environmental Art, Fiber Arts, Folk Art Traditions, Hyperbolic Coral Reef, Painting Techniques, Watercolor

|

| The Hyperbolic Coral Reef project has spread around the globe |

Nature is mysterious and some of the magical colors and patterns of the coral reef are a wonder of nature’s artistry. Surprisingly, vegetables such as kale, frissée and other lettuces mimic the free-flowing, wild patterns found in the coral reef. These products of nature form hyperbolic planes, not explained by Euclidean Geometry.

Crochet, a fiber art that traditionally has utilitarian purpose, holds the power to make this mystery visible to our eyes. With this in mind, various hyperbolic coral reef projects have sprung up around the globe, bringing together crochet artists to call attention to the fact that this natural wonder — something akin to the oceans’ natural forest — is vastly disappearing as a result of pollution, human waste and climate change.

|

| Photo of satellite reef, Föhr, Germany, courtesy Uta Lenk |

The Hyperbolic Coral Reef Project is the brainstorm of Margaret and Christine Wertheim, who founded the Institute for Figuring in Los Angeles to highlight this phenomenon. They based their idea on the discovery of a mathematician at Cornell University, Daina Taimina. Taimina used crochet to unlock a mathematical means to explain the parallel nature of crochet lines in 1997, while the Wertheims further developed a repetoire of reef-life forms: loopy “kelps”, fringed “anemones”, crenelated “sea slugs”, and curlicued “corals.” A simple pattern or algorithm, which has a pure shape can be changed slightly to produce variations and permutations of color and form. The Crochet Reef project began in 2005 and the experiment has involved communities of Reefers, which, like the reef itself, have become worldwide. The Wertheim sisters come from Australia, where the Great Barrier Reef is located, while Taimina is originally from Latvia.

|

| Photo of Actual Coral Reef, from www.thenowpass.com |

These handmade, collaborative works of fiber art have brought together art, science and math to a worldwide community — for the purpose of the sharing a wonder of nature that could be lost. The replica of a coral reef for the Smithsonian Community Reef was a satellite of the Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef Project installed at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in 2010-2011. This project has moved and is on view in the Putnam Museum of History and Natural Science in Davenport, Iowa, where it will remain for 5 years. A former student, Jennifer Lindsay supervised the installation and the public outreach at the Smithsonian and the Putman and is currently coordinating the Artisphere Yarn Bomb in Arlington, Va.

|

| Postcard from the coral reef project in Föhr, Germany |

This past summer, there was an installation at the Museum Kunst der Westkuste on island of Föhr, in Germany. Over 700 artists from the island, and the mainland of Germany and Denmark came together and contributed to the largest of over 20 worldwide projects around the world. At this moment, there is a satellite of the Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef Project at Roanoke College in Salem, Va. It will remain there at the Olin Gallery until March 1, 2013, reminding students at this Liberal Arts College of the fragility of the coral reef.

Artist Elise Richman — who lives on the Puget Sound and teaches at the University of the Puget Sound in Tacoma, Wa — also reminds us that changes are afloat at sea. Richman has different processes of painting, each of which reflect environmental systems and states of flux. In the water-based paintings, she applies inks, acrylics and a liquified powder pigment that has been mixed with powder gum arabic. She pours pools of these paints onto thick sheets of watercolor paper, allowing them to expand, evaporate, be absorbed or intermingle, while using minimum control.

|

| Elise Richman, Each Form Overflows its Present, mixed media on canvas, 2013, photo by Richard Nicol |

The poured paint dries into forms that evoke the contours of islands, water bodies, and/or fluid dynamics. Richman then takes these contours as boundaries that she can transgress in subsequent layers. “I assert my will by deepening the color, adjusting the quality of particular edges and unifying the compositions while maintaining the dynamic sense of flux that the materials activate,” she explains.

More recently, she has used this technique on large-scale canvases. Her newest water-based paintings, such as Each Form Overflows its Present, I, represent an active state of flux as well as topographical formations. They comment, through implication, on the threat of accelerated changes humans have induced on the environment.

|

| Elise Richman, Isle I, oil, 12 x 12, 2008 photo by Richard Nicol |

Richman also has a body of three-dimensional oil paintings made of organic dots which seem to grown from the canvases. As one moves around the small, intricately-detailed paintings, the topographies and colors change in visually dynamic ways, maintaining their aesthetic beauty. These forms represent non-hierarchical environments. “They evoke tide-pools of miniature islands; intimate marine scapes act as

|

| Elise Richman, detail of Pool I, 2010, photo by Richard Nicol |

meditations on the processes of painting, an embodiment of time’s passage, and models of the material world’s interconnectedness,” Richman explained. Each mark, point or dot has its own integrity, yet each is subsumed into a larger whole that has an ethical as well as aesthetic dimension. In short, imbalances of power create exploitations of the natural world and groups of people. Yet this largeness of nature can be maintained in works of art that are personal and meditative. Richman’s website includes works in the encaustic and acrylic paint media. The encaustics have multiple layers, from which she scrapes to represent geological formations.

Copyright Julie Schauer 2010-2016

by admin | Feb 22, 2013 | 19th Century Art, American Art, Hudson River School, Landscape Painting, Nature, The Civil War

|

| Frederic Edwin Church, Meteor of 1860, is in the collection of Judith Filenbaum Hernstadt |

Photos of the asteroid and a meteor which hit in Russia this past week reminded me of Frederick Edwin Church’s painting of a meteor, now on view in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s exhibition, The Civil War and American Art. This month we celebrate President’s Day, Black History Month, and Spielberg’s film of Lincoln in the Oscars, while the exhibition presents the historical and sociological aspects of the civil war as interpreted by artists of that time. Many paintings and photographs on display tell those stories, but there’s also a sub-theme of landscape as metaphor. The scenery of two Hudson River School artists, Church and Sanford Robinson Gifford, present geological and astronomical wonders with deeper meanings.